In the lower room under the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Boston, on my way up to receive Communion, I saw a picture of Mary holding the child Jesus. Its inscription, which I later read, said Our Lady of Częstochowa.

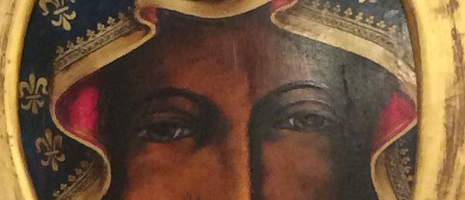

There, Mary looked older than in most images. She had two deep vertical scars across the dark, weathered skin of her right cheek, like trails made by a sled dragged through snow, like two wire toes on a clay bird’s feet, like tracks behind a plow pushed through dirt, turning over dry, faded earth to rich moist black underneath. A deeper horizontal scar crossed the two vertical marks—crooked, the way a child draws the letter A. Her long, straight nose pointed to lips held closed by strength and wisdom, just above a dimple in her chin, like the touch of an index finger. She had eyes she squinted through, not because she didn’t trust you or because you weren’t welcome but because her experiences made her less inclined to smile without meaning it, so you knew you didn’t have to smile, either, when all you wanted was to cry or scream or, for once, just stand and be.

Her shoulders were hunched over from the weight of navy, gold, and rose robes, her head held in a way that said she was not unaware of her heavy halo but that it was somewhat inconsequential, a part of her identity as unassuming as fingernails or the eyebrows framing her eyes. Those eyes that spoke of sadness and strength, of hope and faith that did not blaze but rather glowed like leftover coals, embers orange against the gray dust in the night, even after everyone’s attempts to put them out. I stood and stared at her and knew.

This was a woman I could pray to.

She was not tame but reminded me of the sun, of the furrows it carves in the dirt in unplowed fields when it is dry and dusty and has not rained, will not rain, of the dirt and sweat caught in and running through the lines in the palms of my own hands. She reminded me of wrinkles like terraces and ravines and creases in folded paper letters, of age, and that, yes, I will get older, that I will die, that I will cease to be smooth-faced and unmarked by the turning of light into night, by the exchange of the moon for the sun, day after day after day. She reminded me of beauty, the kind I could cling to like a branch in the side of a cliff while falling, beauty I could be proud of, not in a way that sought gratification through approval but because it was staid like the face of a stone crag, could not be moved by anyone’s attention or inattention and yet still, offered itself. The child Jesus sat on her arm.

She reminded me of my need, let me stand feeling it empty and filled, gnawed at, rubbed raw, pulled and cooled, and yet OK, like a bow across the lowest notes of a cello, like being on the inside of God. This, surely, was the woman my God had wanted to give me when he said, “Behold, your mother.” She was not a model of easy flawlessness and perfection but of suffering and agony equal to that of the man hanging on the cross. A woman not of the well-watered and green but for the times in life when one must draw on the remembrance of water to persevere, the times when one must parse into pinks and golds and reds the brown that seems all around.

A woman not of gardens but of desert.