Augustine of Hippo defines a sign as “a thing, which besides the impression it conveys to the senses, also has the effect of making something else come to mind.”1 For Augustine, signs can be natural (like smoke signaling fire or one’s affect signaling an emotional state), or signs can be conventional (like flags and banners or the words of this sentence). But in all cases, the sign points beyond itself to some other state of affairs or idea, ushering the one who apprehends the sign into something bigger than the sign itself.

In John’s Gospel, Jesus performs signs that signify the truth about who he is. There seem to have been a great number of such signs—John himself suggests in John 20:30 that he only captured a fraction of them—but there are seven particular instances in the Gospel where John identifies an event as a sign, and there is a long tradition of seeing these seven occurrences as an intentional set, arranged by John purposefully. These seven signs in the Fourth Gospel are all miraculous events, and like all signs, they point beyond themselves to some other, bigger reality. According to John 2:11, their purpose is to reveal Jesus’s glory—his magnificence or splendor.

At a wedding in Cana of Galilee, Jesus turns water to wine. A while later, also in Cana, he heals a royal official’s son at a distance. Jesus heals a paralyzed man at the pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem. He feeds a crowd of five thousand in the wilderness with little more than a sack lunch. He heals a man born blind. Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead in Bethany. And a short time later, Jesus himself rises too. These are the signs. Let’s take a closer look to see what they point at.

First, in each of the signs, Jesus brings life into a dead situation.

A young couple celebrates their nuptials in what was likely a multiday community affair. Jesus, his mom, and his disciples are all in attendance, likely along with numerous other people from the surrounding area.

Then they run out of wine.

In our culture this would be a mild embarrassment, quickly forgotten by the couple’s friends and loved ones and immediately overshadowed by the honeymoon for the couple themselves. But in Jesus’s first-century Near Eastern world oriented around a social economy of honor and shame, this would have been a big deal, the kind of thing that the couple’s neighbors would have been whispering about for decades.

Jesus sends some servants to fetch some water, and the enormous embarrassment they would never have lived down is replaced by a more banal and comedic one (this wine is so good they really should have served it earlier in the festivities, when their guests could still taste the difference). The celebration goes on, the social death narrowly avoided because of Jesus’s interference.

The royal official’s son is literally dying, but Jesus acts and the boy lives. The paralyzed man is made whole. Five thousand hungry bellies are filled, the man born blind sees, and Lazarus and Jesus both die and then, a few days later, live again. Jesus draws abundance from lack, health from sickness, life from death. Each of the seven signs in its own way points to this reality.

A second angle at the glory these signs gesture toward is a little less obvious: each sign happens when someone does what Jesus says.

“Fill the jars with water,” Jesus says to a few servants. They do so. “Now draw some out and take it to the master of the banquet” (John 2:7–8 NIV). They do that too. But by then, the water has been made wine. Jesus says to the royal official, “Go, your son will live” (John 4:50). He goes; his son lives. Jesus to the paralyzed man: “Get up! Pick up your mat and walk” (John 5:8). The man who hasn’t walked in thirty-eight years picks up his mat and walks. “Have the people sit down,” Jesus says to his disciples about the hungry crowd (John 6:10). They do, and the people’s bellies are soon filled. “Go, wash in the Pool of Siloam” (John 9:7), says Jesus. The blind man does so and goes home afterward, seeing. “Take away the stone” (John 11:39); they do. “Lazarus, come out!” (John 11:43), and he does!

In each of these first six signs, the transforming moment is always immediately preceded by Jesus telling someone to do something—and them subsequently doing it. These signs that signify the glory of the Word made flesh all flow from mostly ordinary acts of obedience to that Word: fetch some water, go home, get up, tell them to sit down, wash your face, move that stone. Ordinary things all, but the yield is extraordinary. Life overthrows death because someone did some small act that Jesus told them to do. Hope explodes hopelessness because Jesus spoke to someone, and they simply did what he said.

In each case, the obedience is so closely linked with the sign it almost gives the impression that the obedience itself is the true sign—perhaps even the true miracle. In John’s Gospel, it is obedience to Jesus that leads from death to life. In the words of the psalmist, “To whoever obeys my commands, I will reveal my power to deliver” (Ps. 50:23). These six times in John’s Gospel someone obeys Jesus’s commands, and every time Jesus proves powerful to deliver.

Of course, John records no similar command when it comes to Jesus’s ultimate sign—his own resurrection. It would be odd indeed were he to command his own resurrection! But he does issue a few directives after his resurrection. At the mouth of the empty tomb, he tells Mary to do a few things connected to his ascension, and then when he sees the disciples he tells them to receive the Holy Spirit.

Through this latter command, to receive the Holy Spirit, we might notice another feature of this set of obedience-driven miracles.

A few of the commands Jesus issues are, by almost any standard, objectively impossible. Jesus told a man who couldn’t walk to get up and walk—and he does. He told a dead man to come out of the tomb—and he does. Perhaps Jesus, in issuing a command, makes obedience itself possible. This is interesting when applied to some of the synoptic Jesus’s infamous moral commands, so often dismissed because of their impossibility. One example from the Sermon on the Mount should suffice. Jesus proclaims, “But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you,” and then, a few verses later, he says, “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matthew 5:44, 48).

Jesus could not have meant us to actually love our enemies, so it is argued, otherwise a society with the power on the world stage and the number of Christians that contemporary American society is supposed to have would not be able to function. But what if Jesus commanding something impossible includes an implicit promise to graciously make it possible? The logic of John Wesley’s doctrine of Christian perfection runs along these lines, drawing from Jesus’s words in this same passage: Jesus would not have commanded us to be perfect without enabling us by his grace to be so. If Jesus can make a person who is paralyzed walk and a dead man live, why not make a hateful man love their enemy or a totally depraved person perfect? Jesus commanded it; might not the grace of the same Jesus have made it possible?

The prospect of us bumbling humans receiving God’s own Holy Spirit does not seem logically impossible to me, but it does seem at least improbable. Nevertheless, Jesus tells the disciples to receive the Holy Spirit. I imagine John would want us to hear Jesus addressing that same command to us. Receive the Holy Spirit. Can it be?

A third observation about these signs of Jesus in the Gospel of John requires still more patience and care to suss out: there is generally a considerable distance between Jesus himself and the fulfillment of the sign.

For most of the signs, Jesus is entirely hands-off. As far as we readers can tell, he touches neither the water nor the wine at Cana; he seems to have been at least a day’s journey away from the royal official’s son when the son got better; he has no physical contact with the paralyzed man at Bethesda; and he only gets within shouting distance of Lazarus’s tomb. He does touch the eyes of the man born blind—with mud and spit—but the actual healing takes place later, when the man goes away to wash Jesus’s homemade muck off his face.

But even when Jesus is explicitly hands-on, the stories are still told in such a way as to insert distance between Jesus and the experience of the signs. In several of the stories, the insertion is literal physical distance in space. Jesus does not appear to be standing next to the steward when he tastes the water-made-wine; the royal official discovers his son’s healing only after traveling all the way home; and Jesus appears to be nowhere near the pool of Siloam when the man born blind sees the light for the first time.

The most hands-on Jesus gets with the first six signs seems to be the feeding of the five thousand. Jesus takes a young boy’s offering—a pittance of bread and fish—blesses it, and distributes it. We could speculate that Jesus probably delegated the latter, citing the practical difficulties of one person serving five thousand. But this detail does not appear in the text. Regardless, at least one aspect of the impressive result is explicitly mediated by the disciples: he has them gather the abundant leftovers.

But if the feeding of the five thousand is not a great example of Jesus being hands-off or standing at a distance from these miraculous occurrences, it does point to another way that Jesus stands at a distance from the signs’ fulfillment: through ignorance, especially the ignorance of the sign’s beneficiaries or others who witness the sign.

In the story of the mass feeding, it is unclear whether the crowd even knows they have been the beneficiaries of a miracle. In a similar way, the steward, happy couple, and most of the wedding guests may never have known why the quality of wine suddenly improved midway through the party. Did bystanders who witnessed his encounter with Jesus ever hear what happened with the royal official’s son? The paralyzed man was so distracted by the fact that he was walking that he doesn’t even know that it was Jesus who made him whole. The man born blind professed his ignorance about Jesus on the record, under oath, in something of a courtroom scene: “Whether he is a sinner or not, I don’t know. One thing I do know. I was blind but now I see!” (John 9:25).

And once again, the seventh sign seems to fit oddly into this pattern of distance between Jesus and his sign. It’s hard to imagine how he could have distance from his own resurrection. But is he the main beneficiary of his own resurrection or are his disciples? Continuing the pattern of the previous six signs, perhaps the resurrection (insofar as it is something that happens to Jesus) isn’t even the sign. Perhaps, like the others, the sign is something Jesus does to his disciples; perhaps the true sign is the resurrection’s impact on Jesus’s followers. This is expressed nowhere so clearly as in the postresurrection story of Thomas (John 20:24–29).

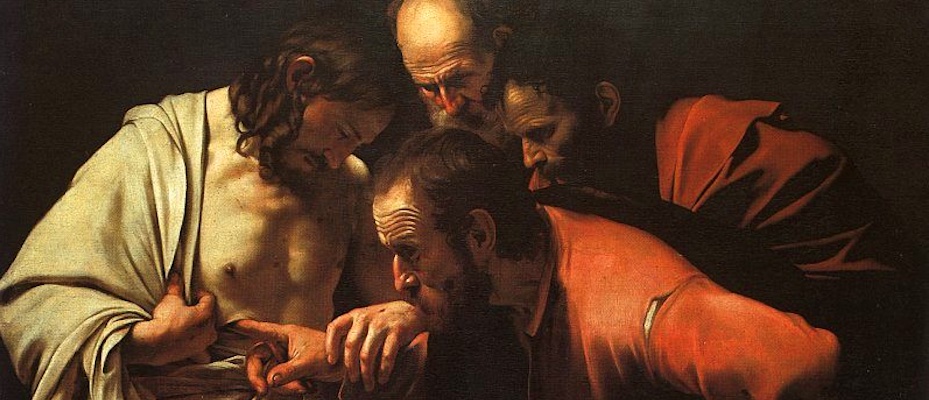

After Jesus appears to his disciples and breathes the Spirit on them, we learn that Thomas had been absent from that particular meeting (a lesson for us all: never miss a Sunday in church—who knows what you might miss!). Hearing the obviously-too-good-to-be-true story of the risen Jesus from his friends, Thomas is understandably a little skeptical. Thomas says he wants to see the nail marks in Jesus’s hands, he wants to touch them, he wants to put his hand into the wound in Jesus’s side, and only then, he declares, he’ll believe. Later, Jesus shows up among them again. This time, Thomas is present, and Jesus offers to him just what he’d demanded. Thomas exclaims, “My Lord and my God,” and Jesus replies with an observation and a beatitude: “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed” (John 20:29).

Most of the time, we moderns assume that real, hard truth must be founded on real, hard empiricism. I need to see it myself to believe it. When pressed, most would admit that none of us has the time to explore everything of consequence. So, absent that opportunity, I need to be able to read a peer-reviewed journal article by someone who has or, at the very least, to hear about it from some putatively trustworthy, authoritative source (e.g., the Atlantic, Wall Street Journal, or for better or worse, my friends on social media). In a parallel way, perhaps we have never literally touched the risen Christ, but might not the New Testament be our peer-reviewed journal, and the great high points of the Christian tradition and our pastors’ Sunday morning sermons (only at their best!) be our other trustworthy, authoritative sources?

“Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed”—I imagine this line spoken mainly for my benefit and for yours. Despite Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s daydream set to canvas, the text never says that Thomas actually poked Jesus’s side wound. But even if he did, Thomas would remain the exception that merely proves the rule. Thomas was in a position to demand to see and to touch the risen Lord. With a few much-ballyhooed exceptions, we disciples who live on this side of the ascension by and large are not in a position to do so. Thomas saw and believed; almost everyone else does not see—what a remarkable miracle that so many believe!

The other six signs rush in to underline the point: in John’s Gospel all the great wonders performed by the preresurrection Jesus happen because of someone’s simple obedience to Jesus, and they all involve the experience of at least some distance from the actual flesh of the Word-made-flesh.

“Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see” (Heb. 11:1). You and I need not see, nor touch the body of our Lord. Our lot is to believe—and to obey.

And, by grace, to be blessed by both.