American moviegoers didn’t let the title Ratatouille stop them. But can they pronounce Munyurangabo?

So try this: moo – new – ra – NGA – bo.

When I asked director Lee Isaac Chung how I should pronounce the title, he told me that he asked his friends in Rwanda. “I am told that there are no accents for the syllables,” he says, “but I have heard consistently that the syllable I emphasize should be stressed—nga.”

Chung heard and experienced a lot of interesting things as he made this, the first feature film in the Kinyarwandan language. It’s a movie about the memories, trials, and daily experiences of those Rwandans striving to go on with life in the aftermath of 1994’s genocidal violence.

Sangwa and Munyurangabo will face a painful test.

It will be a shame if audiences read the premise of Munyurangabo and assume it’s just another Western show of hand-wringing lament over foreign troubles. Chung went to Rwanda to teach Rwandans how to make movies, and he decided that the best way to teach them was to work with them on a new project. As a result, this is a film about Rwanda infused with Rwandese experience.

It follows two teen boys—Sangwa (Eric Ndorunkundiye) and Munyurangabo (Jeff Rutagengwa)—in a long walk across the country. Sangwa and ‘Ngabo travel from the Kigali marketplace (from which they’ve stolen a machete) across the country to the small farming community where Sangwa’s family have continued working the soil since he ran away three years earlier. Sangwa’s homecoming is a tense and emotional affair, but it is also complicated by the fact that his traveling companion is one of the Tutsi, and Sangwa’s father still bears a deep hatred for the Tutsi.

Likewise, ‘Ngabo carries hatred too. Seeing Sangwa’s family together—at work, at play, in intimate conversation—he is painfully reminded of all that has been taken from him. And he keeps his machete within reach, a weapon he plans to use when he finds the man responsible for the murder of his family.

‘Ngabo contemplates his loss and violent plan.

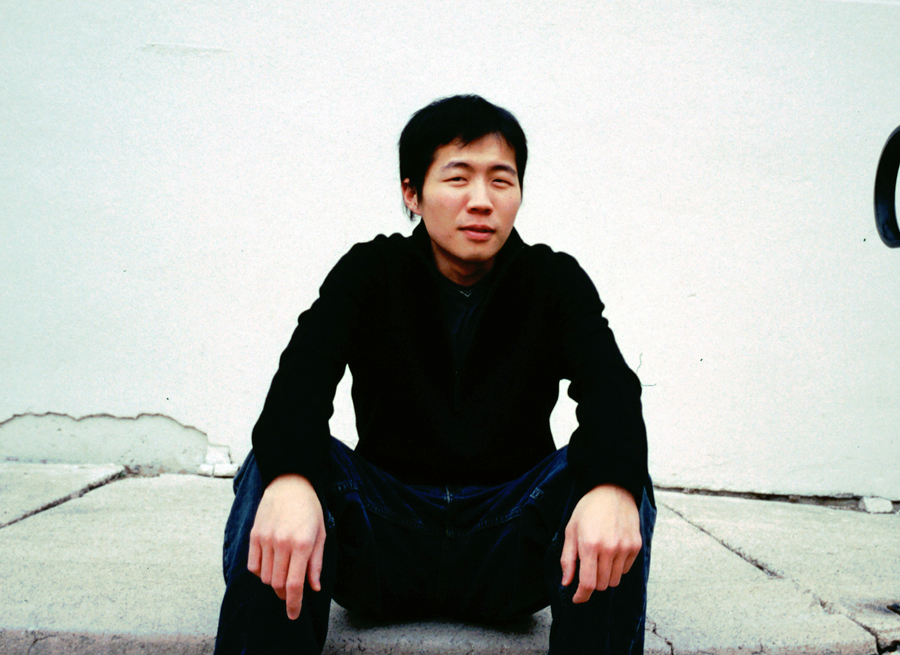

It’s a remarkable story, made even more so by the story of it’s making, and the experience of its director. Chung, whose family emigrated from Korea, have a farm in rural Arkansas where he grew up—not at all the typical Korean immigrant experience. Studying biology at Yale, Chung discovered an interest in the art of filmmaking his senior year, and abandoned his plans for medical school. He studied film at the University of Utah, and became a film instructor himself.

Later, given the opportunity to travel with his wife to Rwanda, in cooperation with the Christian missionary organization Youth With a Mission (YWAM), he inquired to see if anyone in Rwanda wanted instruction in filmmaking, and the surprising enthusiasm of the response convinced him to go. With his friend Samuel Anderson, he sketched the outline for a story, and before long, he was in Rwanda developing that story with Rwandan testimonies, working with Rwandan film students as his crew.

Munyurangabo opened at the Cannes Film Festival in 2007, and garnered high honors at other festivals through that year, including the Grand Jury Prize at the AFI Fest.

It was with great admiration for the quality of Chung’s work, but also for the obvious compassion in his heart, that I sought an opportunity to discuss his project with him.

These are excerpts from our conversation.

PLEASE NOTE:

Our conversation does include discussion of the narrative, including the ending. If you wish to avoid spoilers, you may wish to bookmark this interview and read it after you’ve seen the film.

Congratulations on the distribution of Munyurangabo! Now, instead of just reading about the film, people everywhere can see it!

It has been great to finally get to answer people when they ask when they can see the film.

Have you shown the finished film to many Rwandans? How do they respond to it?

I have shown it to small audiences. I’ve had trouble organizing a large screening for the public in the country. Recently, the national television station broadcast the film, but I haven’t gotten any feedback from it. There is only one station in Rwanda, so that should be good for the ratings at least.

Overall, the responses from Rwandese who have seen the film have been more fulfilling to us than the great response we’ve gotten internationally.

Of course, like any audience, there are people who find the film boring or too long, or lacking in gunfights. But I’ve been very encouraged by the overall response. I haven’t encountered anyone in Rwanda who has felt that this is not a Rwandese film, so I am very proud of that.

Did you learn to speak much of the Kinyarwandan language?

I learned a little. It’s a difficult language, and any time I answer in Kinyarwanda, I receive two minutes of, “He’s speaking Kinyarwanda! That’s so good!” So I haven’t gotten very far in practicing conversation.

Some of the pronunciation mirrors Korean, so I think speaking Korean helps. But speaking some of the words and getting your mind into the pronunciation and rhythm—I think this helps one to get inside the Rwandese mind and heart a bit. I wish I could speak more, but it’s hard to find any text to help learn it. It’s a beautiful language.

Did you decide to go to Africa, and then start imagining a story? Or did you decide to tell this story, and then find a way to go to Africa to make it?

To be honest I think the entire idea came almost all at once. My wife Valerie had been wanting to go back to Rwanda, and she wanted to take me for the first time. I knew that when she goes to Rwanda much of her work is in teaching. That’s changed for her, because she’s actually an art therapist now. She goes and works with people traumatized by the genocide and tries to help them along, with art.

At that time, thinking about what I wanted to do if I went to Rwanda, I thought that the experience I have in teaching is generally in filmmaking. So I asked the Youth with a Mission base if there was any sort of need in Rwanda for teaching video production. They contacted me rather quickly [saying] that they actually had a group of students who were very hungry to learn how to make movies. From that point I knew that I would have these students. I knew that I would go with my wife.

The idea to actually make a film followed pretty quickly after that too, just because I didn’t think there was any better way to teach cinema than to actually make a film. And making a film we needed to be very serious about it. Not just treat it as some sort of exercise, but actually try to form something together, as a group, and hope that it could be a very solid film. So I think that idea came about six months before we left for Rwanda in 2006.

How did you meet your wife Valerie? And how did you get to know your writing partner, Samuel Anderson?

Valerie and I knew each other in college. Sam and I did too; we had one year of overlap in school, and we just kind of knew each other. And then once Sam moved to New York, somebody got in touch with both of us and said that we should get together and chat because we’re both doing film.

I had been openly suspicious about meeting with Sam, because I thought that maybe his tastes would be very different from mine. You always have these feelings that maybe somebody doesn’t know anything about films even if that’s not true or that’s not fair. We got together and realized that we both had the desire to make similar types of films.

We watched Mizoguchi’s* Life of Oharu together, around that time. Maybe just a few months after we had first started meeting, I entertained the idea with him of maybe going to Rwanda and making this film with me and getting involved in the writing process. Munyurangabo is kind of the film that brought us together and so we still work very closely.

How much of your story did you envision before you started work in Rwanda? And how much was plotted out as you worked with the people there?

Sam and I began a series of long email exchanges and weekly meetings in which we discussed our thoughts on the film project. Slowly, we organized an outline of a story of a genocide survivor who embarks on a journey of revenge.

The original idea was that this character would travel to the countryside with a companion, and a family drama would play out. The character would then travel to the killer’s home and decide not to commit revenge. The elements that contribute to this decision changed very little from writing to editing, but the outline for the family drama was very minimal.

We knew the character should encounter the earth—by earth, I mean dirt and mud—but we knew little else.

I arrived in Rwanda a month ahead of Sam, and I continued interviewing and researching this story while writing long emails back to Sam twice a week. This is how we wrote out the rest of the middle portion of the film, including the details that the two characters are from different ethnic groups, and ethnic tensions rise while they are at Sangwa’s home. I didn’t know the reality of this kind of situation until I got to Rwanda and had long conversations with individuals who underwent similar scenarios.

By week seven of my stay, we began shooting with what we had, a ten-page outline of numbered scenes. From there, the entire cast and crew shaped the dialog and other details within each scene as we shot them. The process was very organic, and came out of many intimate conversations—a wonderful way to make a film, a [process of] constant discovery and interaction with others.

This story deals with such painful issues. Was it challenging to tell this story in Rwanda? Were the actors or the locals uncomfortable with the subject matter?

Part of the reason we were able to film so quickly is that the Rwandese who were involved were very enthusiastic about tackling this subject. Even now, my students desire to speak about the genocide and its aftermath in their films.

There is a Rwandan saying that “a man’s tears flow on the inside,” which can mean one should keep his or her emotions hidden. This is true in terms of everyday conversations, but art, dance, song, poetry, or film [can] prove to be a powerful medium of mourning for the Rwandese—which is no different from how art is necessary anywhere in the world.

The only cultural tension arose from my bad New York City habits of wanting to move faster or prioritize work over relationships. Life in Rwanda helps to break these bad habits.

Your film does not explore the religious beliefs of Rwandans. But there is a scene in which a character appears from beyond the grave. Did this idea bother the locals? Or is this a natural part of their storytelling?

This is an element that Sam and I developed outside of Rwanda—the use of magical realism within the flow of the narrative. I don’t know if this is a natural part of their storytelling, but it didn’t seem to be out of the ordinary for the Rwandese who helped make the film or those who have seen it.

I visited a person’s home where a neighbor died, and they believed it was because another family member had arrived with evil spirits. I tried to incorporate this into the film when Gwiza gets sick; the father blames Ngabo for this and other bad developments.

The characters tell such unusual stories in this film—especially Gwiza. Were these stories that you wrote for the script? Or were they given to you by the locals?

Almost all of the stories come from improvisation. Oral storytelling is a very important part of the culture, and I was used to giving speeches wherever I would go. It’s part of what people do when they get together—they tell stories, they share words, their thoughts.

Sam and I envisioned in the outline that Ngabo would encounter moments of oral storytelling. Later, by accident, we discovered the talents of Edouard Bamporiki—and his poetry seemed to be the perfect finale to all of these stories.

It’s tragic and ironic that the oral tradition was part of the genocide, with radio broadcasts by Hutu extremists inciting many of the killings. We wanted to memorialize the root of the oral tradition—how it builds community, family, and, through powerful poems such as Edouard’s, the entire nation.

Gwiza’s jokes and stories are amusing, but I can’t say that I always understood them. What is different about Rwandan storytelling compared to Western storytelling? Were Gwiza’s stories about the animals some kind of social commentary?

Gwiza is played by Muronda, a student in the class I was teaching. Many of the students said that Muronda is the funniest man they know, and his stories and slapstick humor made everyone laugh throughout the shoot.

For his scenes, I asked him to tell his own stories, and the cast and crew ruined a few takes because they would laugh loudly at his jokes. But when they were translated back to me, I had the same response. I had no idea what was funny. I’ll be honest with you, I get the jokes now and I’ve come to appreciate them. I was walking in my neighborhood and saw a woman walking her little dog with clothing on, and the absurdity of what she was doing to this poor animal made me laugh and remember Muronda’s jokes.

We’re far removed from the Rwandan perception of animals. Animals serve a certain function and role there. That’s not to say they are mere objects in Rwanda—they’re not—but they certainly aren’t bound and humiliated to serve as a kind of toy that mirrors human identity. In Rwanda, an animal is an animal; anything else would be absurd. A dog is a dog, a chicken is a chicken. So when Gwiza says he saw a chicken wearing tight pants, that’s very funny; a goat gives birth to a dog—this is funny too. Dogs that wear boots and sweaters are just as funny.

I hope I’m not driving away a certain demographic of readers now. I grew up on a farm, so please extend me some grace.

Your cast was made up of Rwandans who had not acted in films before. Both Eric Ndorunkundiye and Jeff Rutagengwa are fantastic. I was impressed at how they seemed like natural actors, so convincing that they seemed oblivious to the camera. Was this challenging for them?

During casting, it became a running joke that everyone in Rwanda is a good actor because it’s partially true. I don’t know if it is a cultural phenomenon, but I was surprised daily during the casting sessions.

For instance, I was scouting for locations and found the perfect house for the central part of the film—the segment at Sangwa’s house. Edouard Bamporiki, the poet of the film, served as our production manager, and he encouraged me to audition the owners of the house to be in the film. I was skeptical because the owners had been farmers their entire lives, and I assumed, ignorantly, that they would feel nervous with a camera and crew watching them. Their audition was incredible, as though they both came alive and had been practicing to act on camera for a long time. They play Sangwa’s parents in the film, very significant roles.

This seemed to be the case for many of the actors we cast. There were a few people during casting sessions who were not very good, but most were very natural.

Were Jeff and Eric friends before this project? They work very well together.

Part of the reason I wanted to cast them was because they were already best friends before the shoot, and many people in Rwanda told me that the two looked and acted like brothers. I thought this would be an important dimension to the film, since it demonstrates how arbitrary the label of Hutu and Tutsi can be.

In reading other interpretations of your film, some see it as a message of hope. I tend to see it as an expression of questions more than messages. ‘Ngabo’s final decision certainly gives me hope, but the last shot of the movie suggests that reconciliation may be very difficult. What do you hope to convey with that last shot? Do you see your film as “a message of hope,” or a question—or both?

I’m very happy to hear this perspective, since Sam or I didn’t think we were writing a film that projects a message of reconciliation. We wanted to present an image of reconciliation, but we didn’t feel we knew the answers to how reconciliation should take place.

More than that, we wanted to highlight the desire for reconciliation and offer a scenario for it that could even be regarded as a fantasy. Perhaps faith is a lot like this, requiring the act of imagination.

The final image is certainly not meant to be realistic, and it was important for the characters to have their backs turned to each other. The reality of the situation in Rwanda and other parts of the world is that progress and reconciliation are rare. Edouard highlights this in his poem-reconciliation is more than an absence of violence. True justice will occur only when all tragedies (poverty, war, disease) come to cease. Edouard doesn’t say that liberation can come if we do x, y, and z. As you say, he asks a question, “How can liberation come?”

Part of me understands the impossibility of this reconciliation on earth, but the other part believes and hopes that it will [happen]. In the meantime, the work is important. I think that’s what the creation of art can embody—the act of memorializing, mourning, preparing-the act of waiting, which I think isn’t very far from the act of questioning.