I found the video of the lambing to be a bit gross, with the blood and amniotic fluid gushing onto the hay and dirt. I was OK with the elephant birth as long as the sound was off. Two-year-old Clara couldn’t get enough of either. When I first showed her a video of a human birth—a peaceful home water birth—she watched mesmerized and then cut in, “All done! All done! All done!” eyebrows furrowing and voice wavering.

“Was that scary?” I asked, surprised.

She nodded and then burst out, almost weeping, “I want to grow up and push babies out of my uterus too!” At not-quite-three-years-old she perceived the profundity of birthing, saw in a flash how it is both terrifying and beautiful, wonderful and harrowing. I wondered whether I should remind her then that she wasn’t born that way, that I didn’t push her out of my uterus, that she came through an incision in my abdomen.

When our neighbor first heard Clara use the word uterus, she was astonished and marveled, “How does she know the proper names for things?”

“I tell them to her,” I replied.

At the time, I hadn’t yet read Betty Hart and Todd Risley’s research on what they call “The 30 Million Word Gap,” but I had a hunch that young children’s vocabularies expand to hold the words they hear from those who care for them. Hart and Risley go even further and suggest that verbal poverty is what keeps the poor poor. For my part, I wasn’t leaving any gaps in my daughter’s early vocabulary development if I could help it. I was, as much as I could, giving her an inheritance of words, the mother lode, if you will, with which to know and name the world.

What I didn’t realize was how, in the next several months, I would have occasion to need others to give me words, words to rise out of my own kind of poverty, my own destitution. I would need to relearn words I thought I’d learned before and give names to realities I’d never before encountered.

Throughout my second pregnancy, Clara’s exuberant sisterly love expressed itself daily as she patted and kissed my belly, chiming: “I love you, baby brother! Stay safe in Mommy’s uterus.” Her evening prayer for the last month of my pregnancy was an imitation of my own. In her small melodic voice she asked God to “help baby brother stay head down and come out without complication near his due date”—the polysyllabic “complication” sounding large and lyrical on her lips.

When I learned in early October, thirty-six weeks pregnant, that the local hospitals were instituting CDC flu-season recommendations to prohibit all children, including siblings, from attending births or visiting moms and babies in the hospital, I objected. I decided I would make my own choice out of joy rather than fear. I decided to attempt a home birth.

A homebirth midwife in Southern California is not hard to come by. Although still a rare choice statistically, the homebirth rate has been on the rise since 2004. “It picked up even more,” said our midwife, Liz, “after The Business of Being Born came out in 2008.”

I considered myself very lucky to live in a time and in a region of the country where access to a variety of birthing options is readily available. Although many women are interested in attempting a vaginal birth after a prior caesarean—what I have learned to call a VBAC—many of those women do not find support from their care provider or hospital, even though VBAC has been officially deemed a safe and appropriate option for most women and their babies. I planned to be part of the 60 to 80 percent of women who succeed in their VBAC attempt.

When Clara awoke on Monday morning, October 27, I had been having contractions every five minutes since two o’clock in the morning. She was excited with us as we anticipated that this was the day. She watched closely while my husband, Jason, coached me through a couple contractions. Then, when he went to gather some of the home birthing paraphernalia, she decided to step in to help me herself, her strong, empathetic spirit in full force.

“Take a deep breath,” she told me as the next contraction began, her hand on my back. “Slow and deep,” she said in perfect imitation of her dad, “Let it go.” She came around the front of me as I sat on the birthing ball so I could rest my head on her shoulder. The pain hardly registered.

But the hours of fitful contractions wore on. Clara went off to play, eat, and nap. Despair redounded on despair as my labor stuttered and started, stretching into a second night.

Clara slept. My mother slept. Our labor assistant, Gianna, went home to sleep. Our midwife dozed on the couch. Her assistant, Lauren, slumped in a chair. Even I slept as I could. Jason, the lone watchman, held me in the warm water of the inflatable birthing pool, my overripe belly floating weightlessly in a last defiance of gravity, the utter silence of the night broken only by my cries. They came every three minutes as a new wave of pain wrenched me momentarily from sleep into the semiconsciousness of labor. Jason watched through our sliding glass patio doors as the flush of dawn spread over the horizon. He watched the maintenance men arriving at the apartment unit utility shack across the lawn: humanity going about its ho-hum daily routine while our private drama unfolded wordlessly on the other side of the glass. Five hours he held me in the stillness.

I would like to write here that my ponderous nine-month sojourn ended as it began: in my lover’s arms in our home. I would like to write it and, in the writing, make it so. But that is not what happened.

My dream of a home birth dissipated as my baby boy’s heart rate began to suffer significant deceleration with each contraction. Significant deceleration—I realize as I write the term how formal it is, how medical, how removed, how safe. I hold it at arms length and my own pulse stays steady. It doesn’t get under the skin like dropped, like His heart rate dropped. I could hear it through the handheld Doppler fetal monitor pressed against my belly. I heard the pum–pum–pum of his slow-motion drum. I knew that rhythm was wrong; it wasn’t the pa-pum-pa-pum-pa-pum I’d heard before.

I was suddenly surrounded with hands turning me to one side and then another. I was numb, shell-shocked, delirious with pain and exhaustion. I followed directions like a swollen Gumby as Liz, Gianna, and Lauren repositioned me this way and that. Liz later told me it was the first time in her ten years of practicing in which she was unable to correct fetal heart decelerations through maternal positioning.

I was dilated to nine centimeters, one centimeter away from being ready to push out the baby. It was dawn on October 28. Clara, newly awake and fresh, had put on her swimsuit, eager to climb into the birthing pool with me and meet her brother. I didn’t have time to explain; everyone was caught up in a flurry of activity. I was being rushed off to a place I didn’t want to go, the place where I would be cut open for my son and cut off from my daughter. I left Clara standing in her swimsuit, the eager anticipation on her face changing to confusion and disappointment.

When Clara was four months old, she reached up to touch my face for the first time. As I nursed and rocked her to sleep in the dimly lit room, her tiny fingers brushed against my cheek and chin. Her eyes met mine. I saw knowledge and volition there, a first beacon flaring up in a new land. We had reached across uncharted seas and suddenly discovered each other. In that flash of euphoria, as I beheld her vast intelligence and beauty, one agonizing thought ran through me: One day, she will leave. One day, I then saw with an ache, I would no longer be the one to nurture and comfort her, to enfold her in my arms, to introduce her to the world in wonder. She would sail away to discover her own new worlds. I was already waving goodbye.

Our obstetrician met us at the hospital and informed us that baby boy was indeed “making the call” for surgery. Contraction-stopping drugs paradoxically made every muscle in my body shake violently. En route to the operating room, I lay supine on a gurney, my legs bent and my knees knocking wildly together, every muscle from head to toe tensing uncontrollably.

“I can’t stop shaking,” I said to anyone, to no one. I was surrounded by a swarm of medical people I’d never met before.

While the anesthesiologist debated whether to lay me on my side or sit me up as he inserted the spinal tap into my shaking torso, my obstetrician offered to hold me. Like a child, I let him lift me forward and fold me to his chest, his arms around my arms, his hand gently squeezing above my left elbow for reassurance. I rested my chin on his shoulder. In the containment of his firm hold, the shaking stopped and the spinal tap was easily started. I believe I murmured a semicoherent “Thank you for being so kind to me.” I felt small as they lay me flat in cruciform for surgery.

As the warm numbing sensation of anesthesia started in my feet and legs and began working its way up my body, a team of masked people exposed me. They flitted around, prepping me, affixing various tubes, leads, and wires.

A day or two later, I would find one metal lead still stuck under my arm. “What’s this?” I would ask my postpartum nurse. “Oh!” she would say, half-amused, half-embarrassed, as she yanked it off. I would still see the round mark embossed on my skin two weeks afterward. I would take a photograph to memorialize it. It was another landmark on my body like the incision: Here, the markers say. Here is where they measured. Here is where they cut.

In the operating room, somebody—I didn’t see who—scrubbed down my abdomen with an antiseptic solution. An equally anonymous person, or maybe the same person, shaved off hairs along the bikini line over the pubic bone. At some point the screen went up so that my head and chest were separated from the rest of me. I was bodiless, floating in a sea of numbness with infinite horizons. The anesthesiologist’s voice, also bodiless, occasionally addressed me. Jason was ushered in, took my hand, and anchored me.

According to Jason, the doctors were talking about football as they began the surgery. At the time, I registered no words, only amorphous sound lapping around the periphery of my consciousness. I could feel tugging and pushing sensations in my midsection as the doctors sliced through five layers of abdominal skin, tissue, and muscle, manually separating the muscle down to the pubic bone. They separated my organs from the surgical area with spatulas, and, cutting through the uterine wall, pulled out the baby.

When I began to feel sick, the invisible anesthesiologist produced a kidney-shaped pan out of the haze and placed it on the table along the side of my face. I turned my head slightly and uselessly coughed into the air. In a few moments the nausea subsided.

Somewhere in that ocean of the surreal, a baby was held over the screen, and he cried. His face was red and scrunched, hanging forward as someone held him by the armpits. In an instant, he disappeared again. “9:44,” someone called out, documenting the time of birth. I heard the crew whisking my baby across the room for his initial exams and procedures.

Clara was at a friend’s house when the call came that her brother was born. Immediately, she clapped and cheered; then her eyes filled with tears as she realized she was missing it. As there were parks and friends to distract her, however, she quickly recovered. In the coming days, my mother took Clara to playgrounds, merry-go-rounds, Disneyland, and other happy places. I forget how resilient children are. I did not consider how quickly Clara might accept her loss and move on.

After the surgery, I lay on the operating table for another twenty minutes while the surgeons scraped out the placenta, sewed up the uterus, flushed the abdominal cavity, and sutured the cut. When I was rolled into the recovery room to join my husband and son, I was high from the narcotics and itchy like chickenpox from the spinal tap. I lay awake the first night, unable to sleep, unable to roll over or sit up, the machines connected to me chiming, pulsing, beeping relentlessly. I couldn’t stop rubbing my tingling face.

Twelve hours after surgery, it was time to take my first postpartum walk. I needed two nurses to help me out of bed and across the room to the toilet. On that long, slow journey, I slid one foot a few inches forward and then the other, a nurse supporting me by the arms. An assisting nurse wheeled the IV pole along next to me and held open the bathroom door. When it came to cleaning myself, I was as helpless as my newborn.

I requested an early release from the hospital and came home mid-morning on October 30, wearing pajamas, shuffling slowly to avoid aggravating the wound. I laid the baby down for a nap in the back room and waited. When Clara came in the front door, I was sitting in the same room where I had last seen her standing in her swimsuit. I had returned to her two days later, a sibling in tow, my body broken.

“Hello, Clara,” I said quietly, “Come climb up onto my lap. I’m sorry I cannot lift you. I have a big owie in my middle.” Those were all the words I had. I did not yet fully perceive how significantly my relationship with my beloved firstborn would be changed, had already changed.

I would have sobbed convulsively in the days that followed, but such sound and shaking would have hurt too much. To laugh or cry, I needed a pillow to splint the incision. To avoid the pain more completely, I stayed rigid and silent, letting the tears fall without show. My bed became my refuge. I left guests in the living room and retreated there alone or with my baby. I found myself calling him “Clara.” In the angelic, genderless beauty of the newborn person, he looked just like she had looked. I adored him. He was perfect, his mewing and rooting easily satisfied. We sated each other and slept.

Friends brought meals, sent cards and messages. I steeled myself against the barrage of well-intentioned exhortations to “Just be grateful for a healthy baby.” I was reminded of how often we—how often I—try to relieve another’s pain by minimizing or dismissing it: “All that matters is that you are both alive and well.” We say, “Just be grateful,” as if the human heart were such a flat and tame thing that it could abide only one feeling or disposition at a time, as if it could not simultaneously accommodate both joy and grief, as if it were too small and narrow an ark to admit every living pair.

Every living pair—I was not prepared for the frequent moments when both children would need me simultaneously. It was mine to choose who would cry and who would be comforted. I often felt as if I were throwing the life preserver to the newborn while I watched Clara go under the waves. No. I was the one sinking beneath the waves, pulling her down with me. As I did, I sang nervous, high-pitched songs to myself and tried to block out her crying and clinging. I felt trapped in a persona I didn’t know at all and wanted less. When I fought, on occasion, to break through the surface of suffused anger, to integrate and reconnect, I often met, often tasted a bitter rebuff as Clara pushed me away in retaliating anger of her own. In these lowest of postpartum valleys, I hated her for reminding me how I had failed her and what we had lost.

I felt that I hated her, but I knew it was myself I hated. In her neediness and frailty, I saw my own, and it terrified me. In unutterable shame, I found myself destitute, devoid of motherly affection, filled with loathing for my daughter and my self.

The rhetoric of a prosecuting attorney runs through my head: The defendant is clearly unfit to birth or raise children. Shall I admit the evidence? Shall I hold myself to answer? Shall I indict? I bang the gavel and dismiss the case. Some days the prosecution resubmits the complaint. Shall I schedule the arraignment? Shall I plead guilty or not guilty?

Seven months after my son’s birth, I finally went to a psychiatrist. He helped me name the illness I had been unable to name alone: “I have postpartum depression,” I recited to myself, to my husband, to my friends. The words felt strange to say aloud, and I wasn’t sure I knew what they meant. I was one of the 12 to 25 percent of mothers who experience postpartum depression, what psychologists identify as a normal response to a stressful life event.

Contrary to popular opinion, postpartum depression is not caused by hormonal changes or imbalance, does not go away on its own, and has serious consequences for mothers and their families. In her comprehensive survey of postpartum depression research, Kathleen A. Kendall-Tackett identifies the many risk factors, which vary from woman to woman. They range from a negative birth experience, pain, or sleep deprivation to psychological history and characteristics, lack of social support, stressful life events, and socioeconomic situation. Infant temperament and health can also play a role. As the causes are many, so are the cures. Effective treatment may include psychotherapy, community intervention, exercise, and other alternative and complementary therapies. Some of these options are as effective as antidepressants in facilitating healing and recovery.[1] As it turns out, what women need most is to be heard and accepted. Did we need scientific research to tell us this?

My doctor offered me antidepressants. I considered and then declined, realizing, finally, that I knew what care I needed most. I needed to come to terms with grief, to give utterance to the words and the narrative I was living but hadn’t known how to express. Though I’d traveled it a thousand times before, I had found the path of grief to be strange country. I had thought that I had grieved my first cesarean delivery with Clara. I had thought I was prepared for a VBAC with my second child. Apparently, I had merely thrashed around in hedges of denial.

“Every woman attempting a VBAC is grieving her previous cesarean,” my midwife had told me while I was in labor with my son. She had asked everyone else to leave the room. I had been experiencing irregular labor for over fifteen hours without moving into a sustained pattern. Contractions had been short and irregular from dawn until dusk.

“What are you afraid of?” she asked sitting on the exercise ball facing me. The question unarmed me.

I thought of Clara’s birth, how I had labored sporadically and ineffectively for over two days at home, how I had finally arrived at the hospital to discover I had reached a mere seven centimeters in dilation. I remembered the desolation, the fetal distress, the call for an emergency C-section.

“I am afraid I can’t do this,” I confessed, keeping my eyes from meeting Liz’s face.

“What else?”

“I am afraid my body will fail me.”

When I had named my fears, Liz reframed them and asked me to repeat after her: “Even though I am afraid that I can’t do this, even though I am afraid my body will fail me, I completely and totally accept myself.”

While I felt like some lotus hippie type, sitting there on the futon cross-legged mumbling these affirmations, I did what she told me. I repeated after her until, unwilled, the tension I’d been clutching began to dissolve into tears. From that hour on, I contracted every three minutes with longer and stronger contractions.

One morning in the late spring, while Jason and the baby still slept and the soft, early morning light illuminated the living room, I held Clara in the rocking chair. I clasped her close to me, her head on my shoulder, and asked for her forgiveness. Did she remember when we had the pool in our living room, the same room we sat in now, and how she had put on her swimsuit to get in the pool with me and meet her baby brother? Did she remember how Mommy and Daddy had to go the hospital while she had not been allowed to come? Of course she remembered.

“I felt very mad and sad,” I told her. “I was mad and sad for a long time,” I said, “and sometimes, I was mean. I am so sorry for being mean to you. Will you please forgive me?”

She did. We held each other while the sunlight slid across the wall.

Summer came but the coastal June gloom lingered. I drove Clara to a burger joint for a long overdue mother-daughter date. I waited for a returning surge of affection, the burning attachment I had felt toward her from her birth until her brother’s, the love I had felt as sharply as a knife in the chest. Awkward like a blind date, I smiled weakly at her across the restaurant table. I told her how I loved her. I named the things I liked about her, told her I was so glad to have a special outing just with her. It was all true, but I felt none of it. I watched her play on the outdoor gym, wishing for all the world that I could feel some joy in the moment.

We got our nails done on our second date. We fought less often, and most days were better than they had been all year. A few were just as bad. We did well. We messed up. We said sorry. We slept. We tried again.

On a hot, late-summer day, I sat outside with neighbors while the children played in an inflatable swimming pool. There was Clara in nothing but cotton shorts—she had decided somewhere in the morning that her swimsuit was cramping her style. Her brother couldn’t get enough of her as he looked on from his stroller seat and laughed. As I watched Clara splashing and dancing around, I realized I was smiling, smiling from inside, and I was startled by the sudden realization of a timid, quiet joy hovering somewhere in the vicinity of my chest. I wanted to kiss both my darlings and hold them close—both my darlings: my daughter and my son.

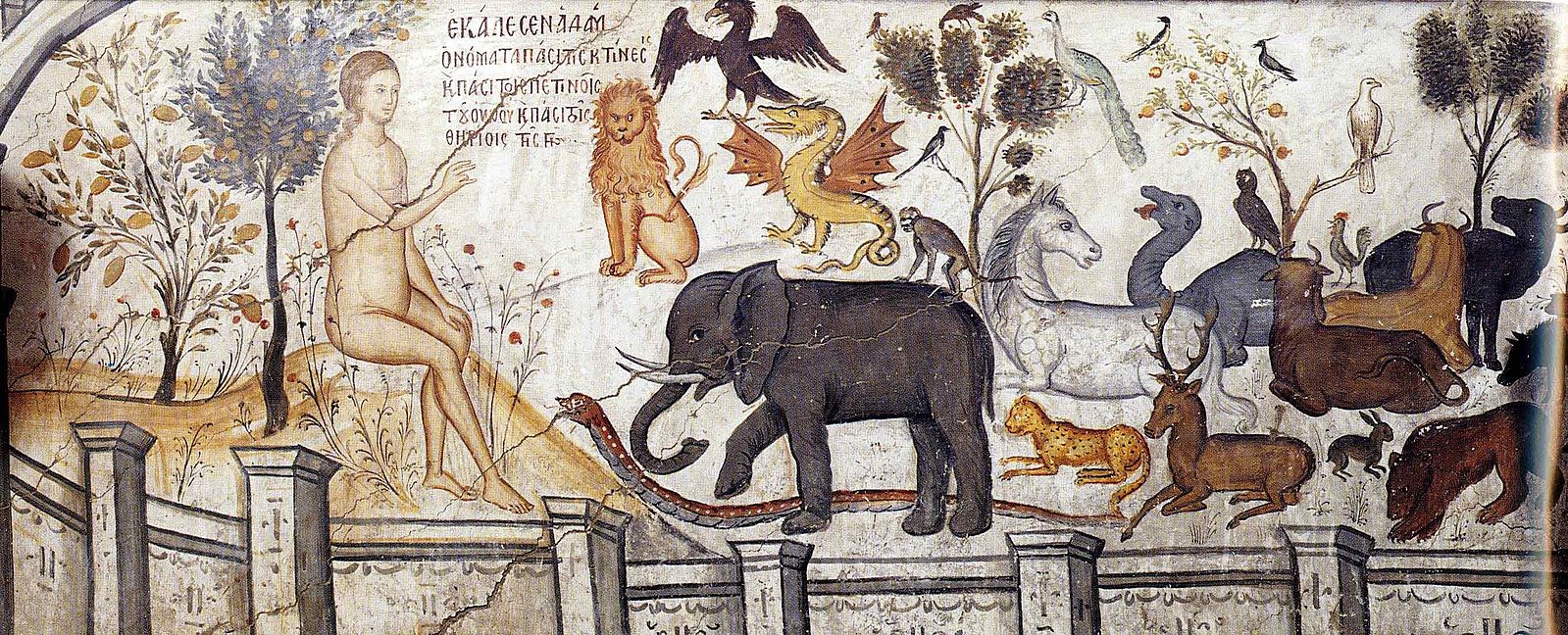

We have named our son Jude, from the Hebrew, meaning “praise” or “thanksgiving.” Lately, at fourteen months, he is fascinated with animals. His favorite pastime is to point out all the four-footed creatures he comes across, to name them and make their sounds. He is a toddling Adam in his child’s paradise.

Clara and I, we two Eves, have other wild things to name. To us also is given a power, not of judging but of naming. I choose to name, to grieve, and to forgive.

Beginning in the center, I name the abdomen: the walls of this strange transient house of flesh, an elastic tent lifting in the wind of breath, stretching with the mystery of desire, of life and longing, vibrating with the rhythm of the heart: Abdomen-abdomen-abdomen.

That hidden tent within a tent, I name uterus, the word, like the thing signified, hidden behind a small taut O of lips, becoming protracted. It is a tucked-away universe that love populates and love empties, and populates and empties again. A muted universe over which I have total control and no control at all. It is the riddle of motherhood, a Pandora’s box of joy and loss, of attachment and release.

To name the thin, raised ridge of skin over the pubic bone, I bare my teeth, agitating the air with a fricative stop, then open my jaw in a restrained roar: scar. It is a line marking the longitude of pain and the latitude of life, a geography of birthing, an anatomy of finitude, sacrifice, grief.

Without shame or judgment, I call them by their proper names, those animals within me: the anatomical, the affective, the noetic. In naming, owning, and forgiving, I gain not a paradise lost, or some other nostalgia, but something more substantial; I find perched in the soul that feathery phoenix singing its unassailable song.

[1] See Kathleen A. Kendall-Tackett, Kathleen, Depression in New Mothers: Causes, Consequences, and Treatment Alternatives, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009).