Each year I aim to see all of the films nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars. I fell a bit short of that goal this year, but I did see Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) at one of my favorite independent theaters in Denver.1 In February, Birdman won the top prize at the Oscars in a race that was quite tight.

As a philosopher specifically interested in existentialism, particularly as it is used to describe the philosophy that emphasizes the existence of the individual as entirely free, I was ecstatic that this film received such attention. In the context of the film and my work with existentialism, freedom is the ability to make choices that determine one’s sense of self in a seemingly meaningless world. Existentialism, then, is the pursuit of meaning in relation to self-development. Given the existential themes in Birdman, this essay is a commentary for each of us as individuals. The plight (or flight) of Birdman is universally applicable yet must be subjectively appropriated. Is our life one of struggle with struggle being the absolute end? Or does the external struggle lead to an internal sense of meaning? This is the existential crisis that Birdman vividly encapsulates.

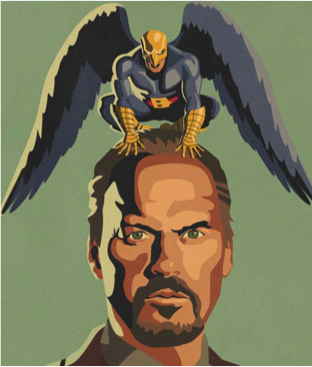

Birdman focuses on a past-his-prime action movie star, Riggan Thompson (played by original Batman actor Michael Keaton), attempting a comeback in a Broadway play. We meet Riggan in the first scene and hear an ominous, Batman-like voice speak the first line of dialog, “How did I get here?” It’s a simple yet profound question that we all ask ourselves at some point in our lives. Philosopher Søren Kierkegaard asks a series of similar questions: “Where am I? . . . Who am I? How did I get into the world?”2 Behind these questions lurk deeper issues. It is natural for each of us to feel lost at some point in our lives, and Riggan is that lost man, a man without an identity whose despair is profound. The Birdman character that taunts Riggan is his lost ideal, the standard of personal meaning he once possessed. This Birdman occasionally appears on screen as the manifestation of Riggan’s chaotic state of mind. There’s turmoil between Riggan and Birdman, as their identity was once one: Riggan was Birdman, and Riggan’s departure from the role of Birdman necessitated a departure from his sense of self, a movement which thrusts him into a search for the meaning of his existence. And so Birdman tells the story of a man searching for meaning while leaving open the possibility that there is no meaning for that man.

Early in the film, Riggan’s play is clearly not going well. He seems lost, and he is perpetually haunted by his former heroic self, the Birdman character who brought him fame. For Riggan, and certainly for his Birdman alter ego, returning to his famous character, making Birdman 4 as one character jokes, would bring meaning back to his life. Yet in his quest for personal meaning, Riggan recognizes the triviality in repeating the past. He understands that Birdman represents success and fame in the eyes of his audience, while also understanding that for him personally, Birdman is a lie. He distances himself from the role because Birdman is a false self, an easy self, one given meaning by a faceless and fleeting crowd. His task, then, shifts to discovering his true self independently of Birdman.

Riggan’s rejection of Birdman is an apparently healthy move, but one that leaves him wandering in chaos. Riggan woefully jokes about all he has left: “I’m the answer to a fucking Trivial Pursuit question.” As a man with a lost sense of self, Riggan begins comparing himself to the standards of success set by others. He hears reports of actors making millions in Hollywood blockbusters, something he once achieved as Birdman. He struggles to center himself in the shadow of a popular costar. His rattled relationship with his daughter shatters any remaining evidence of self. In the most vivid scene in the film, his daughter, Sam, yells at him:

. . . You want to feel relevant again. Well, there’s a whole world out there where people fight to be relevant every day. And you act like it doesn’t even exist! Things are happening in a place that you willfully ignore, a place that has already forgotten you. I mean, who are you? You hate bloggers. You make fun of Twitter. You don’t even have a Facebook page. You’re the one who doesn’t exist. You’re doing this because you’re scared to death, like the rest of us, that you don’t matter. And you know what? You’re right. You don’t. It’s not important. You’re not important. Get used to it.

Sam articulates a sense that meaning comes from others, that the cloud of online voices establishes a hierarchy of worth, but that Riggan’s yearning for approval from the masses leaves him empty. Angst and despair overwhelm his search for meaning as he finds no meaning, no validation, not even from his daughter or his closest confidants.

I sympathize with Riggan and the existential premise of Birdman. At heart, I think we all do. The tendency to seek approval from others, including through social networking platforms, is common. We reach out for validation as we attempt to vanquish the near-paralyzing fear that we don’t matter. Perhaps we get a response, a series of Facebook likes that provides momentary bliss before making us fade back into meaninglessness. Or perhaps we get no response, which only reinforces the fear that we do not matter.

This is the tension of which Kierkegaard writes. We seek affirmation and meaning in the crowd, but the crowd is an abstract, fleeting entity that can never stabilize or substantiate meaning. Kierkegaard writes, “The crowd possesses no idealism . . . it is always the victim of appearances.” And elsewhere he writes, “There is a view of life that holds that wherever the multitude is, there, too, is the truth—that truth itself needs to have the multitude on its side. There is another view of life that holds that wherever the multitude is, there is untruth.”3 Kierkegaard equates the crowd with untruth, declaring that meaning cannot be conveyed by so many voices and still contain meaning. In a crowd of popularity, truth is absent; it is nowhere to be found. Like many of us, Riggan seeks affirmation in the crowd. Kierkegaard wouldn’t be surprised that Riggan finds himself in despair.

The rather hopeless search for meaning in Birdman is the reason I both love and dread the film. That, to me, is also the draw of existential thought in general. The captivating aspect of the film is Riggan, a character who vividly reminds me of myself. Yet his search for meaning also unsettles me each time I watch it. I compare my own journey to Riggan’s, and I come to the haunting realization that I’m listening to my own Birdman, my own fabricated ideals of identity that have been instilled by the crowd. Perhaps that is simply the narrative of life. There is a fine line between discovering meaning and despairingly wandering in search for it. It is no wonder the author of Ecclesiastes writes that everything is meaningless—when we seek meaning in the crowd, we lose.

Yet we all want to win. We all want endue our existence with meaning. Whereas other existentialists create meaning for themselves (e.g., Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre), Kierkegaard as a Christian existentialist says humankind finds meaning and healthy selfhood in the relationship between self and God, a relationship constituted by faith. For Kierkegaard, the search for meaning in existence is futile without using one’s own passions to believe in God. If God is truth, he suggests, the leap into belief is the meaning we’ve all been seeking.

Relationship with God is a leap that many of us cannot make. The crowd speaks against this meaning or ignores it altogether. For the world, finding meaning in God is absurd. But sometimes faith is formed, as Kierkegaard famously says in Fear and Trembling, by virtue of the absurd.4 We believe in spite of nearly insurmountable evidence against God’s existence. We believe despite God not making sense.

Birdman’s title includes the parenthetical phrase “The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance.” Absurdity and ignorance are not categories we typically ascribe to faith formation and self-development. Neither are absurdity and ignorance synonymous, yet given the context of this film they are similar. Ignorance here refers to Riggan as an amateur theater director. He has no training, no experience in the field. Yet his premiere, to the shock of critics, is a masterpiece. Riggan’s performance is transparent; it brings forth authenticity and truth. This is accomplished in spite of his ignorance. It was absurd for Riggan to pursue this goal. Even those closest to him thought the feat absurd. Yet he leapt into an event that led to meaning.

To the existentialist Christian, absurdity and ignorance are attributes that are often necessary. Kierkegaard views Abraham’s faith in God in Genesis 22 as absurd in the eyes of the world. In Birdman, Riggan’s brilliant performance on stage occurs by virtue of ignorance: he has actualized his selfhood in a meaningful way that has transcended the crowd. While ultimately achieving grand reviews for his play, Riggan recognizes his selfhood as more important than mass fame.

The last scene of the movie leaves much open to interpretation, testifying to the murky and difficult narrative of the film. Riggan, in the hospital after a gunshot wound during the final scene of his play, sees birds flying above his private room. He steps out onto the ledge, several stories above the ground. He moves. The scene changes focus to his daughter entering the room. She looks, hopelessly, for her father in the empty room. He’s gone, but she notices an open window. Terrified, she walks towards it and looks downward. She expects to see her father’s lifeless body on the unrelenting cement below, but she doesn’t. She gazes upward with a face full of curiosity and hope.

What does she see?

We do not know.

Did Riggan plunge to his death in despair and meaninglessness? Possibly. Yet I like to think that Riggan is flying, both literally and figuratively, after realizing his selfhood. Given the fantastical realism of the film, my interpretation is not wildly out of the question. Riggan’s leap of faith is a leap past the known and into the absurd, where he and his daughter finally recognize who he is. Riggan has found himself. In Kierkegaard’s Repetition, a text considering the love and despair of an anonymous man, he discusses selfhood in a manner that fits Riggan’s end, “I am myself again. This ‘self’ that someone else would not pick up off the street I have once again. The split that was in my being is healed; I am united again.”5

In the same way, I hope to take that same leap on a daily basis. It’s a leap into relationship with God that leaves me feeling light in the face of despair, sets me free with wings when the voices of the crowd try to tie me down. It is there that I am myself. Let us all jump from our hospital room windows and into the arms of God.

- Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), directed by Alejandro G. Iñárritu (Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2014).

- Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling/Repetition, trans. and ed. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), 200.

- Kierkegaard, The Point of View for My Work as an Author: A Report to History, trans. Walter Lowrie (New York, NY: Harper, 1962), 47; Kierkegaard, Søren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Notebooks, vol. 4, ed. Bruce H. Kirmmse (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 54.

- See Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling/Repetition, trans. and ed. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), 36.

- Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling/Repetition, 220.