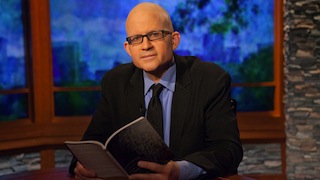

Christian Wiman is one of America’s most important poets. He is the editor of Poetry magazine, the author of several poetry and essay collections, and a revered contributor to such prestigious publications as the Harvard Divinity Bulletin and the New Yorker. His forthcoming book, My Bright Abyss: Meditations of a Modern Believer, explores the central themes of his work, including frailty, illness, and the love of God. In this interview, Wiman discusses his work, his attention to lament and evil, and his perspective concerning the role of spirituality in contemporary American poetry.

The Other Journal (TOJ): I’ve spent the past year reading your essay “Gazing into the Abyss” from the American Scholar and it is one of the best apologetics I’ve read for poetry and a spiritual life. What brought you to put this essay together? What do you have to say about it now?

Christian Wiman (CW): I’ve had a handful of essays in my life that came to me as poems—that is to say, they just came. That particular essay was written at a period of real crisis. I had just been diagnosed with cancer, and the news I was getting from various doctors in Chicago and elsewhere made my situation seem very dire. And yet I didn’t feel dire, at least not absolutely. I felt, as I say in the essay, abradingly alive, an effect of being in love with the world and one woman and the life that it seemed I was going to lose.

TOJ: In that essay, you consider several passages from Simone Weil, who happens to be a long favorite of mine—what other passages of her work speak to you?

CW: I’ve always been bowled over by these lines: “We must take the feeling of being home into exile. / We must be rooted in the absence of a place.” For many years, this seemed to perfectly articulate the dynamic in which I found myself, and it gave me a way to think of that dynamic in positive terms rather than negative ones. I also love “He who has not experienced the presence of God cannot feel his absence,” which led me to say at the end of one of my own essays “I never truly felt the pain of unbelief until I began to believe.”[1]

TOJ: I taught Every Riven Thing to my writing students last fall, and I was surprised that a group of evangelical Christian youth not only identified closely with the book but that they followed its forms so well. What has surprised or challenged you about people’s responses to the book?[2]

CW: I have not been surprised by what you might call the “religious” responses to the book, only because I think there is a hunger in this country right now—even among people who would call themselves evangelicals—for an art that speaks to people at, well, the level of art. There’s not much out there, and most of it comes from unbelievers. As for following the forms, that does surprise (and delight) me!

In the more secular literary world where I live, some people have not had such a warm response to the so-called religious content in the book. Clive James, in an otherwise positive review, said that those particular poems were the worst in the book. James is an atheist, though, which may explain that response. Or maybe those poems really are the worst in the book. Who knows! That is not for me to say. All I know is that I had to write them.[3]

TOJ: I hear so much lament in Every Riven Thing, lament over the possibilities of impending loss. How do the ideas of lament and evil connect or rub against each other for you?

CW: I just read a passage from the poet Eleanor Wilner the other day in which she said that protest and lament could also be forms of praise. I agree completely. Yes, there is a lot of lament in Every Riven Thing, but I feel in my bones that it is, ultimately, a book of praise and joy. After all, the Psalms are full of lament. The whole Bible is full of lament.[4]

I know that many people link evil and illness—including, disappointingly, Jesus—but I find the idea either benighted or offensive. Little kids get cancer. Babies get cancer. Were they being evil? Evil is what humans do, not some judgment visited upon them for what they have done.

TOJ: You wrote “The Limit” ten years ago, and I hear some significant differences in your approaches to pain and to personal narrative in your span of work over the past ten years. Do you hear this? Or do you hear something else?[5]

CW: I have much more hope and fullness of spirit than when I wrote “The Limit,” though that essay was itself an attempt to find my way to those things. I do hear a great difference in my work over the past ten years, which (I hope!) has gone from relying wholly on emptiness and absence as fuel for art to including experiences of abundance and joy. The difference, in a word, though there is no word, is God.

TOJ: Is it still true that “pain may be its own reprieve,” as you wrote in “The Limit”? It reminds me of the poem “One Time,” in which you wrote “praise to the pain scalding us towards each other.” Do these two lines resonate with each other still for you?[6]

CW: That’s a very interesting connection and one I hadn’t thought of. The lines do resonate with each other, though they are also very different. The first is enclosed and deeply informed by Simone Weil, whose thinking, though brilliant, has real limitations. The second leads to a “beyond”: it is not simply a reprieve but a release into some fulfillment and grace.

[1] Weil, A Simone Weil Reader, ed. George A. Panichas (New York, NY: McKay, 1977), 356; Weil quoted in Wiman, Ambition and Survival: Becoming a Poet (Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2007), 138; and Wiman, “My Bright Abyss,” American Scholar, Winter 2009, http://theamericanscholar.org/my-bright-abyss/.

[2] Wiman, Every Riven Thing: Poems (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

[3] See James, “Rocket Man,” review of Every Riven Thing: Poems, by Christian Wiman, Financial Times, November 12, 2010, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/b755fae4-ede9-11df-8616-00144feab49a.html#axzz1o6o2HgxC.

[4] See Wilner et al., “One Whole Voice,” Poetry, February 2012, http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/article/243400.

[5] See Wiman, “The Limit,” Threepenny Review 87 (2001): http://www.threepennyreview.com/samples/wiman_f01.html.

[6] Wiman, “One Time,” in Every Riven Thing, 29.