Since January 1, 2009, I have watched 607 movies. I know because I keep track. I log every one, the good ones and the lousy ones, in a Google Doc along with some notes. I do this because I think movies matter, both to me and to those around me. Beyond providing entertainment or escape, movies matter in my life. They provide a place of revelation, disruption, and personal transformation. This has been increasingly true as my posture toward film has become more intentional, but it was true before I was conscious of it as well.

As a seventeen-year-old, my impending graduation from high school felt like sitting in a train car, anxiously waiting to leave the station, and like being tied to the tracks while the locomotive came steaming at me. I was living the unoriginal story of the terrible high school experience. Because I wasn’t particularly athletic, studious, or musically gifted, I felt insignificant in my environment and as if I were trapped in roles I did not want to play. Graduation provided me the escape I longed for, but leaving a place is one thing and knowing where you’re going is something else entirely, a something for which I had no plans or ideas of how to proceed. My fear and excitement mixed together to form an anxious unsettledness.

While showing up to church on Sunday was as regular for me as putting on pants in the morning, Bible stories, sermons, and hymns had become a bit like white noise. If they had something to say, I was not hearing it. Church had not become a negative influence on me, but very little of it was connecting with me in any meaningful way. In 1994, as I found myself wandering in the liminal space between what was and whatever was to be, it wasn’t the Bible that I returned to over and over again; it was my local theater where I would first watch and then rewatch Pulp Fiction.

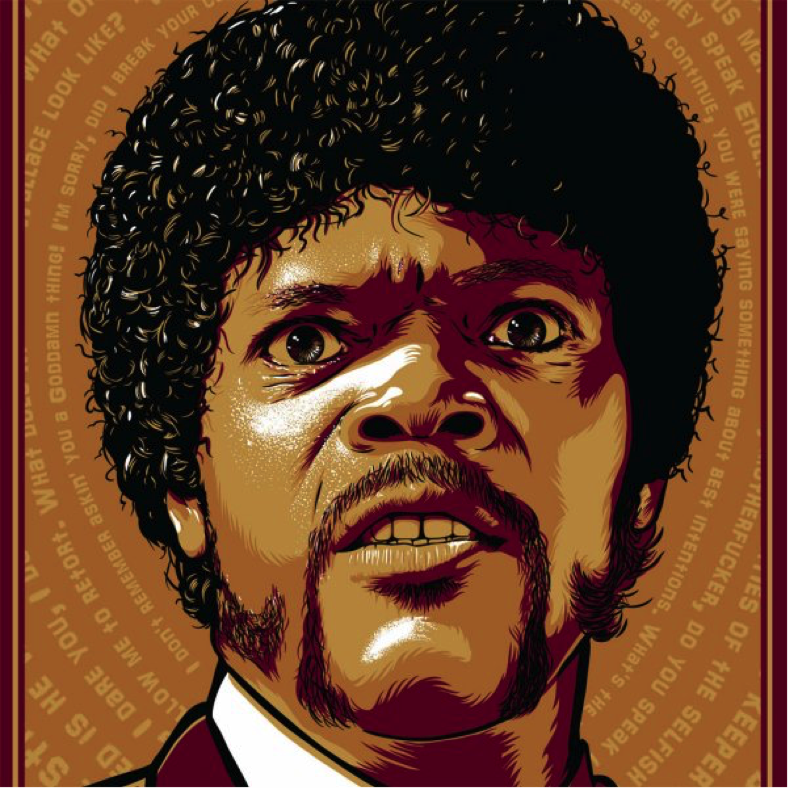

Almost twenty years later, I look back with the clarity of time and perspective and make sense of that choice. There are certainly parallels between my angst, confusion, and longing and that of Jules Winnfield (Samuel L. Jackson), the foul-mouthed, Bible-quoting assassin in Pulp Fiction who just wanted to find a deeper purpose in life, a calling. But in the moment, I don’t know that I could have made sense of why Pulp Fiction felt so, dare I say, important.

There is not a lot of debate about whether churchgoers believe that culture and film are formative. All one needs to do is look at what happens when a film like 50 Shades of Grey hits theaters. Petitions and boycotts are organized to keep the film from playing, generally citing the danger it poses to young people—despite the fact that the book sold most of its copies to middle-aged woman. This sort of fear is rooted in the idea that if Christians see other people behaving in a certain way, they will follow suit. Thus, a film like Old Fashion surfaces at the same time as 50 Shades and is embraced by many in the church. Marketed by its producers as the alternative to 50 Shades, it is the story of a man who will not allow himself to be in a room alone with a woman who is not his wife. Again, this sort of phenomenon makes sense when you understand that fear of mimicry is what is driving people; in fact, it actually functions as a sound form of logic. Violence, sex, drugs—the more we watch them on the screen, the more we will mimic that behavior in our own lives. Therefore, we should shield our eyes from such things and focus on images of people living their lives in a more pure and pious way.

Personally, I am unsatisfied with the idea that the alternative to 50 Shades of Grey, for people of faith or anyone else, is Old Fashion. I spent fifteen years working with high school students as a pastor, and painting a picture of a life of faith that is compelling to a seventeen-year-old is difficult enough; suggesting to that seventeen-year-old that the alternative to BDSM is old-school courtship is not helping. American high school students are just as interested in aggressive, painful sexual encounters as they are in avoiding kissing until they get married. These extremes are not helping anyone plot out a path forward.

The problem with this posture—that is, fear of mimicry—toward film is that if we were to apply it to the characters and stories of the biblical text, we’d have to rip out half of the pages. King David—the “man after [God’s] own heart” (1 Sam. 13:14 NIV)—he’s out. You can’t tell his story without sex, lies, and murder. That is his story. That’s what is so compelling about him. And what about a story like the one about Samson? He killed people with the jawbone of a dead animal, and that was a story taught to me as a kid in Sunday school. Why are we not afraid of mimicry with Samson, but we are with Kill Bill?

It can’t be because we want people to mimic these biblical characters. We must believe these stories have something more to offer us, something more complicated and possibly more important than offering role models. The answer is more complex and nuanced than a redemptive story arch. That may work with David, but I’m not sure Samson’s last scene, as he kills himself and everyone present, provides a redeemed story line we should all mimic with our lives. But for some reason we trust ourselves (and our children) with this story. I think that is because we have a more robust posture toward the biblical text, one that is concerned with more than just mimicry, and we need to develop that same posture toward culture.

In his essay An Experiment in Criticism, C. S. Lewis writes, “In reading great literature I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. Like the night sky in the Greek poem, I see with a myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do.” Every voice mattered to Lewis. Each perspective provided him an opportunity to see more clearly. It was an insatiable appetite for perspectives that caused Lewis to state, “Even the eyes of all humanity are not enough. I regret that the brutes cannot write books.”[1] Lewis was not claiming that all books are great literature and are therefore worth reading. Rather, he was making a statement about what great literature does for the reader. For Lewis, books provided a way to see the world through the eyes of someone else. It provided him an alternative perspective. He could have just as easily been writing about film.

Lewis did not see the stories of great literature as a pool in which to swim in hopes of finding characters to mimic. He didn’t want to copy the behavior of all of people in books; rather, he wanted to learn from them, to understand them and gain from their experiences. I feel similarly about film. Although there are undoubtedly aspects of characters that I incorporate into my own self and in that sense mimic them, I don’t see this as the great gift of film (or conversely its great danger). I have come to see film as a way of experiencing stories I both want to live and would never want to experience firsthand. When I watch American Beauty, I have no desire to be Lester (Kevin Spacey), feeling so alone and flirting with high school girls. But Lester’s loneliness does resonate with my own, and as I watch him make decisions that are both harmful and healing, I am given the great gift of a vicarious experience. As a result, I am on a continual search for another voice, another perspective, another way to gain eyes that see and ears that hear the world as it truly is in all its complexity and wonder.

The Christian philosopher Paul Tillich describes revelation as “an ecstatic experience of the ground-of-being that shakes, transforms or heals.”[2] He also understood revelation to be, among other things, experiences that demand a change of lifestyle or of thinking.[3] In a word: disruption. I wonder if this was part of Lewis’s desire for more perspectives—as he saw the world through the eyes of another, it disrupted his own, and in that sense, he was experiencing the revelatory possibilities of good literature. This is what film and other forms of art have become for me, experiences of disruption that bring forth healing and transformation.

When we show up to a film, we drag our story along with us. We can’t escape our own lens on life, a lens that has been shaped by our very personal set of experiences. We necessarily come from somewhere and someone(s), and those realities dramatically affect the way we view the world. We have been told all kinds of things about where we should be going, how we should get there, and with whom we should be journeying. The mix tape of ideas and worldviews you have been taught, rejected, held fast to, and are currently debating are much of what makes you who you are. This, combined with the love and trauma that fills your life, is the material of the story you are living. You bring that with you everywhere you go, like a messily packed bag you can’t gate check, you have to carry it onboard (and into the theater).

But you’re also not that unique. You’re not the only person coming from where you come from. You are a part of a number of communities, groups, and cohorts. Each of those collectives has their own stories as well. Your race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, geography, nationality, and numerous other realities lump you in with a host of tribes with whom you share some common stories. As a middle-class, Midwestern, Generation X academic, I am a part of all kinds of stories. None of them define me entirely, but all of them give shape to how I see and experience the world—including the movies I watch.

Most of us would agree that movies are a fun, entertaining way to spend a few hours. But film moves from simply being entertainment to being something more when our personal story and the stories of the collectives we are a part of overlap with the stories of the film we are watching in a way that shakes, transforms, or heals us. Put another way, it is when the overlapping of stories provide a place of revelation. It seems that most of the time we want to see our humanity and ourselves on the screen and have it acknowledged in ways that make us feel good. Life feels hectic and hard so when we get to Friday night, we’re looking to be entertained. This is a valuable role that film plays in our lives—rest and play are vital to our health. Yet if all we look for in film and art is an affirmation of our current self or a way to check out of our lives for a while, it will never become a place of transformation. If all we want in this overlapping of our story and the film’s story is an experience of our way of life being confirmed, we are then closed off to any prophetic function film might have in our lives. We are entering the theater with our eyes and ears closed; we shouldn’t be surprised that we fail to see and hear.

While at Sundance this past January, I attended a panel discussion on faith in film. It was made up of a handful of people who produce and market films to what is often called the “faith-based” audience. It was a fascinating experience to hear them talk about what “Christians” want. I use quotes there very intentionally. The reality is that the group of people they were talking about are very likely Christian, but they in no way represent all Christians. At one point one of the panelists stated that when it comes to film Christians just want to be told they are right. This is what grounds the commercial success of a film like God’s Not Dead.

The statement made by the panelist is very likely correct in many cases, and it is a statement that could be made of a number of groups—religious, political, and otherwise. But what do we make of this statement in light of how Tillich understands and articulates the nature of revelation? If revelation comes through moments of disruption, being told you are right is arguably the antithesis of revelation. It’s no wonder many in the church don’t see film as a place of deep importance. Jesus clearly called for people to have eyes that see and ears that hear—how ironic it is that Christians would come to be known as people who show up doing the very opposite of that.

I love movies. I always have. So as I made my way back to the theater again and again in 1994, part of that was simply me doing what I love to do. But as Clive Marsh and Vaughan Roberts state in their book Personal Jesus: How Popular Music Shapes Our Souls, “Meaning-making occurs as a dimension of what people do when they are engaged in things they do regularly and enjoy doing.”[4] For me, that’s movies. Jules Winnfield’s story came to me through a medium that speaks to me. But it wasn’t just the medium that mattered; it was the embodiment of wondering made possible in and through the medium that resonated with me. Watching someone search for value and purpose in and among the foulness of the places and people he encountered disrupted my sense of how we search for meaning. Jules wanted the same thing I wanted, and he even used some of the same language I would to describe his longing. But his search felt unfettered by any rules or religiosity. He was being set free and I wanted to the same thing for myself.

Then, and even now, it is hard to find many people who would agree that Pulp Fiction could be a locus of God’s voice. Along with the rest of Quentin Tarantino’s films, it would likely fall on the list of things to avoid for Christians who are looking to focus on that which is pure and holy. But I cannot avoid the reality, nor do I wish to, that Pulp Fiction played a strange role in helping me make sense of life as an adolescent. It not only made sense to me; it made sense of me.

To long for meaning and value is to be human. As Jules began to question his life as a hit man, it blew me away. He was nothing like me and yet exactly like me. I was accustomed to memorizing Scripture in order to edify my life; he was quoting it before he shot people because it made him sound tough. Yet he started to wrestle with what the words actually meant in a way that I had never done. He was leaving simplicity behind and walking toward the complexity of life in the hope of finding a new kind of simplicity on the other side. That was what I was trying to do. I wasn’t drawn to this film because I wanted to become like Jules Winnfield. I was drawn in again and again because I already was like Jules Winnfield—a man on a search for direction and purpose. There is no question that Pulp Fiction captured me because of the stylized writing of Tarantino and the nonlinear storytelling, which I had never experienced before. But that wasn’t why I bought ticket after ticket. This story was an embodiment of the path I was walking and it allowed me to see it with new eyes. Yes, it made me laugh and cringe, but it also gave me hope and a vision of what taking the next step in life might look like. It doesn’t matter whether or not Tarantino wrote the film for this reason; when my story, the film’s story, and the other stories in my life all got together in the dark, I experienced light.

Opening ourselves up to the perspective of others and experiencing the disruption that comes along with that is what film can give us, can do in us. And I, like Tillich, can think of no better way to describe that than revelation.

[1] Lewis, An Experiment in Criticism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1961), 141 and 140.

[2] Tillich quoted in Jonathan Brant’s book Paul Tillich and the Possibility of Revelation through Film (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012), 73.

[3] Ibid., 246.

[4] Marsh and Roberts, Personal Jesus: How Popular Music Shapes Our Souls (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 26.