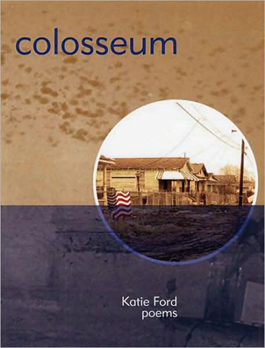

Katie Ford, Colosseum (Saint Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2008), 60 pages, $15.00 paper. Click here

Katie Ford, Colosseum (Saint Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2008), 60 pages, $15.00 paper. Click here to buy Colosseum from Amazon.com and support The Other Journal.

When the lights go down in Colosseum, Katie Ford’s second collection of poetry, we find ourselves in the poet’s cranial theater, an old-fashioned movie palace of flickering reels and irregular splicing. It is here that the book’s preoccupation unfolds: a remembering of New Orleans during and after Hurricane Katrina. And it’s here that the memory landscape shifts from history book to watercolor dream cycle, nightmarish in its images and vagaries. Showing a deft sense of humor, or perhaps just irony, Ford includes a poem about the late great New Orleans movie theater lost to fire months after the hurricane, the “Coliseum Theatre”—it is, of course, an elegy.

To say the poems in Colosseum record anxiety, trauma, and a stunned sense of coping might belittle Ford’s surprising chemistry in mixing the loss of New Orleans with the destruction and devastation of the classical world. At first it might seem that the thematic thread is a project, and arbitrary—why Rome? Why not Rhodes? Only after reading and re-reading Colosseum did I see Ford’s book as an attempt to honor New Orleans by placing its destruction into the tradition of the great dead: Athens, Rome, Carthage, Alexandria. Is Ford’s point that every vanquished city is worthy of such high simile, or is it just New Orleans? Feeling runs so high in this collection that I must admit that reading it put me in mind of testimonies from Vietnam War veterans, especially this from Michael Herr’s Dispatches:

[. . .] it took the war to teach it, that you were as responsible for everything you saw as you were for everything you did. The problem was that you didn’t always know what you were seeing until later, maybe years later, that a lot of it never made it in at all, it just stayed stored there in your eyes.1

Memory seeps through Colosseum in a way that makes the washing away of an American city a personal event, not a public one; what’s stored in the brain is the poet’s gift of comparisons and her desire to equate loss for loss: Rome with New Orleans, the Colossus of Rhodes with the breaking down of the body. The lesson of Rome is that anything can fall, and its ruins will be taken back by time and nature. The body will decompose, new buildings will be built, and civilization will move on and gradually forget the details.

The opening poem, “Beirut,” gives us the leveling of another city and invokes gods who pity the dead enough to resurrect them in ashes and make them sing. If this is true, Ford writes, “our songs // will have to be plagues.” So rises the curtain on the collection’s speaker and her mausoleum. What’s wonderful and awful is the gesture Ford makes in her title poem “Colosseum” with her nod to psychiatry, where literal ruins soon give way to mental ruins:

How great is the darkness in which we grope,

William James said, not speaking of the earth, but the mind

split into caves and plinth from which to watch

its one great fight.

With this move, the reader watches the speaker stumble through a mental landscape broken by storm, populated by ghosts and bodies. In “The Shape of Us,” Pompeii is discovered “beneath calcifications of ash / because certain hollows looked human,” and those human shapes occur and recur in Colosseum, whether it’s in “Earth,” brief and clear as a Greek epitaph, “If you respect the dead / and recall where they died / by this time tomorrow / there will be nowhere to walk,” or in “Flag,” where a woman “spills onto her porch to show / she has opened her wrists. What did she use? / She used the wind.”

Water, ash, ringing bells, animals adrift, locusts singing, the vessel, and the body, always the body, return through each of the book’s sections. Whatever disaster the speaker survives, the mind rationalizes and the body soaks up the rest, as Ford writes of Nagasaki, “less charred where the bodies / had absorbed all they could.”

Ford’s choice to spell colosseum in its less familiar form was curious to me. My best guess is that Coliseum is too modern, too regular, and might draw unwarranted attention to the burned down theater. Perhaps Colosseum was chosen to linguistically tie up closer to Colossus, the crumbled wonder of the world referred to in “Koi,” another human shape that suffers a fall:

After hearing how camels carted away the broken

Colossus of Rhodes, showing us how to carry

and build back our destroyed selves,hearing there was once a hand

that first learned to turn

an infant right in the womb,that there was, inside Michelangelo, an Isaiah to carve out

the David, the idea, the one buried

in us who can slay the enormities.

This emphasis on the buried idea beside the buried and unburied bodies of the storm imposes additional conflict—we are always digging to uncover, digging to bury, and will the task ever be done? The idea that saves is hidden, meanwhile the dead lie everywhere and the gods, where are they? They’ve deserted. Those of us who have never witnessed such destruction might hope to rebuild the ruins, to renew the broken city, but the poet isn’t there yet. Disaster, Ford says, leaves you alone and your city devastated—“when one is the site of so much pain, one must pray / to be abandoned.” Intellectually, it seems, the poet wishes to find comfort in grass growing over the graves, but this desire is balanced by her refusal to enjoy the mysteries of earthly renewal, to reject the ruined city and the agent of its destruction. Colosseum shows us that survival can be a mean thing, and time, instead of healing, can also compound the wound. It’s better not to look back—choose a new city, new gods, plant a new garden.