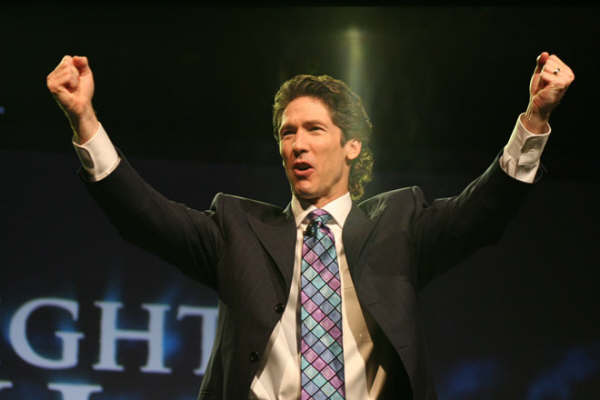

Joel Osteen has every reason to smile. The man known as the “smiling preacher” earns top billing as the leader of Lakewood Church, the nation’s largest church and 43,500 members strong. His books debut as New York Times bestsellers. He looks at home seated across from Larry King, Barbara Walters, and the feisty cast of The View. Seven million Americans watch his television broadcast weekly, making him America’s most-watched inspirational figure.

Informed observers might see Osteen as yet another example of the typical megaministry: big churches and big personalities to lead them. Yet Osteen and prosperity preachers like him represent a new breed of American pastor.

Prosperity teachers preach a message marked by four themes: faith, health, wealth, and victory. For pastors like Osteen, their gospel centers on faith. Faith is as an activator, a power that unleashes spiritual forces and turns the spoken word into reality. This faith is confirmed by wealth and health. It is measured in both the wallet (one’s personal wealth) and in the body (one’s personal health), making material reality the measure of faith. Adherents of this prosperity gospel expect faith to be marked by victory. Believers trust that culture holds no political, social, or economic impediment to faith, and no circumstance can stop believers from living in total victory here on earth. All four hallmarks emphasize demonstrable results, a faith that may be calculated by the outcome of a successful life. Though they argue that Christian prosperity differs from worldly acquisitiveness, these Christians recognize that their message inscribes materiality with spiritual meaning. Inverting the well-worn American mantra that things must be seen to be believed, their gospel rewards those who believe in order to see.

Millions of Americans have fallen in love with the prosperity gospel and its new kind of preacher. Charming though not effusive, polished but not slick, these favored few seem just as comfortable on Good Morning America as behind their megachurch Sunday pulpits. Podcasts, Internet streaming, and daily television programming carry their sermons to millions. They cultivate their fame with personal appearances in sold-out arenas. The megachurch ministerial elite dominate not only religious media networks, like Pat Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network or the Crouches’ Trinity Broadcasting Network, but secular outlets as well, becoming mainstays on stations like Fox Television and Black Entertainment Television. Their titles line the Religion/Inspiration aisles from Walmart to Barnes & Noble, and some climb the charts of the New York Times best-sellers list. The Senate buzzes about these celebrities’ high profit margins, and bloggers and media pundits debate each ministerial expenditure.1 Loved or hated, they are never forgotten. At almost any moment, day or night, the American public can tune in to see these familiar faces and a consistent message: God desires to bless you.

Consider the ten largest churches in the United States. How many American churchgoers would recognize the names Craig Groeschel, Ed Young, Dave Stone, or Kerry Shook? These senior pastors lead some of America’s largest churches, yet their names rarely make headlines. Conversely, prosperity icons such as Creflo Dollar, Eddie Long, Fred Price, and Rod Parsley earn national reputations despite having far smaller congregations. Why? Certainly, prosperity megachurch leaders owe much to their deft use of Internet and television broadcasting to cultivate audiences far exceeding their Sunday attendance. Yet prosperity teachers primarily separate themselves from their other media-savvy colleagues by featuring the senior pastor as the main attraction. Their personal lives—their style, habits, spouse, children, education, friendships, sense of divine calling and so on—eclipse the congregations they serve to become the focus of spiritual meaning-making.

Religious figures in the public square expect their lives to be scrutinized, but prosperity teachers invite an even closer look. They tender their biographies as living proof of the prosperity gospel and the power of faith to produce results. Naturally, the success of their congregations serves as a barometer of their divine calling. Congregations bursting with activity and new building projects become ministerial necessities. But the spotlight remains fixed on the one who casts this corporate vision of the abundant life. Prosperity preachers defend their mansions, personal jets, and designer clothing (if they have them) with an invitation to join the action. “The gospel to the poor,” concluded the Texas evangelist Kenneth Copeland, “is that Jesus has come and they don’t have to be poor anymore!”

The perfection of their personal lives serve as a perpetual reminder of God’s calling upon them. From the 1980s onward, smiling wives have joined their husbands on stage as co-pastors, making their marriage an example and testimony. Husband-and-wife teams typically duplicate the traditional order of conservative households, upholding the husband’s spiritual oversight but also encouraging women to exercise their own expertise. Creflo Dollar, for example, headlines national tours while Taffi Dollar focuses on her own women’s conferences. Joel and Victoria Osteen hold their interlaced fingers in a triumphant salute at the close of every conference. When marriages fail, ministries falter. When Paula White’s marriage to her co-pastor Randy fell apart, disapproval dogged her every step. During her interview with Larry King, an e-mail question from a San Antonio viewer stated it bluntly: “How can you preach from the pulpit regarding marriage when yours failed?” White replied that she was committed “never to waste my trials in life, to find purpose in all things”—critics were not convinced. Juanita Bynum received heated criticism for divorcing her husband and fellow prosperity pastor Thomas Weeks III, even after he was jailed for allegedly assaulting her in an Atlanta parking lot. Believers turn instead toward those upon whom fortune smiled.

What kind of religious celebrity is this? This mode of pastoral authority reflects an extreme embodiment of what the historian Brooks Holifield called the “charisma of person.”2 A model of charismatic authority emphasizes individual gifting over educational credentials or even clerical office. Pastors must bear their ministries on their backs, boasting only those special gifts and abilities granted to them. Yet since the televangelism scandals of the late 1980s, its teachers have gone to great lengths to emphasize their standing as consummate professionals. They speak of special skills, training, and knowledge without which the church—and churchgoers—cannot thrive. Borrowing language from the inspirational authorities of corporate America, pastors began to refer to themselves as “life coaches” rather than evangelists. They offer “tools” and resources to better people’s lives rather than hosting telethons or begging for pledges. America’s new breed of pastor expects their lives and counsel to be a public testimony, evident to all. They clamor to be recognized by secular authorities as spiritually capable of rejuvenated health and finances. T. D. Jakes has issued marital advice both from the largest pulpits in America and on Dr. Phil’s television program. Pastor Paula White has appeared in exercise videos and beside Donald Trump as his personal pastor. They do not define their ministry by their priestly duties—as purveyors of baptism, communion, weddings, and funerals—but as experts in a life well lived. Dressed like corporate titans, they come to Sunday service as if straight from the boardroom on Sunday morning, stopping long enough to offer their congregations some advice.

A new kind of pastor is on the rise. As a historian, I cannot say what this breed of celebrity should mean to faith communities as they seek to articulate a theology and practice of ministerial calling. It is clear, however, that those who wish to remain relevant in the spiritual marketplace must recognize how more and more contemporary preachers rely on a new ethic of success. The new pastoral celebrities seamlessly blend overlapping secular and religious authority, communicating in theology and practice that good Christians should always have something to smile about.

Notes

Click the image below to learn more about the book mentioned in this essay. Purchasing books from links in the journal will help support The Other Journal.

1. In 2007, Senator Chuck Grassley of the Senate Finance Committee launched an investigation of six famous prosperity teachers: Joyce Meyer, Benny Hinn, Creflo Dollar, Paula White, Eddie Long, and Kenneth and Gloria Copeland. In 2009, according to Grassley, Meyer and Hinn had been cleared; Long and the Copelands submitted “incomplete responses”; and Dollar declined to comply with the investigation. See United States Committee on Finance Memorandum, March 12, 2009,http://finance.senate.gov/press/Gpress/2009/prg031209a.pdf, accessed Feb 2, 2010.

2. E. Brooks Holifield, God’s Ambassadors: A History of the Christian Clergy in America (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007), 2.