Read part one of our interview, plus two more of John Leax’s poems (and audio) here.

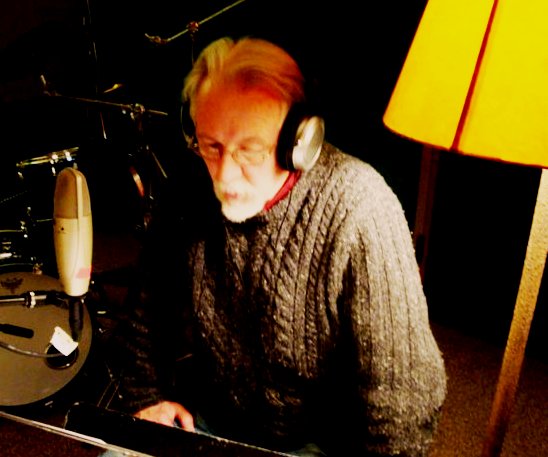

An elder statesman in art and faith circles, John Leax (Jack to friends) is a poet and essayist of hard-earned, humble wisdom, and as such, he avoids the spotlight. The author of books like Country Labors: Poems for All Seasons and Out Walking: Reflections on our Place in the Natural World, he would rather be working in the garden than at the podium, and since retiring from a long teaching career at Houghton College, Jack has done just that. But he has also been busy putting the finishing touches on three forthcoming books. In Part I of this interview, Leax reads two poems, “4 AM Meditation” and “Late Night,” and discusses his early days as a poet of faith and his adoption of Wendell Berry’s metaphor of “at-one-ment” in his life and writing. Here, in Part II, Leax shares about the process of compiling his new books and his efforts to break with the confessional voice. At the end of the interview are two poems by Leax, “Walking the Circuit around the Cornfield I Walk Every Day, I Glimpse the Nature of Creation and Submit to Joy” and “Waiting for Rain I Remember Three Old Poets Who Wondered the Slopes of Flat Mountain in My Youth,” which he reads aloud.

The Other Journal (TOJ): Many readers know you best for Grace Is Where I Live. How do you account for the popularity of that book?

John Leax (JL) [laughs]: I can’t. It puzzles me—though I think its reputation has exceeded its sales! The only suggestion I would make is that it is a collection of pieces that were written over a long period of time. Each essay was written to address some specific question for a particular audience in a particular time. I suspect that particularity may be what explains the immediacy, the concreteness, or whatever it is that people respond to in it. It’s a puzzling book for me because it was written over so many years that when I put it together, I felt I was gathering things I had left behind. I’m not sure I know the person who wrote that book anymore.

TOJ: In Tabloid News, you take on bizarre premises such as “Smartest Ape in the World Goes to College” and one of my favorites, “Duck Hunters Shoot Angel.” How did this come about, in light of your previous work as a poet and essayist?

JL: That’s an excellent question to follow what I just said about not knowing the person who wrote Grace Is Where I Live. I suspect a reader of Grace Is Where I Live wouldn’t recognize the author of it as the writer of Tabloid News.

In Grace, there’s a piece called “Sabbatical Journal,” in which I wrote about the constraints of the confessional mode. Up through Country Labors, when you come across the word “I” in one of my poems, it’s me. It’s nobody else; it’s not a persona. I was trying to tell not only Truth with a capital “T,” but also a literal truth: if something is described in the poem, it more or less really happened. I began to find that very constraining. I was becoming increasingly private, reclusive as a person and not wanting to talk about myself. But I didn’t know how to change the terms of the relationship I’d had with my readers. I’d come to the point where I either had to find some way to change or just quit writing poems.

The device of Tabloid News, in which there could be no confusion with the events and the characters of the poems with reality, gave me a way to make that break with the confessional voice. It was a turning point. The bizarreness of the situations let me consider and say things that I previously couldn’t address or say because of the expectations I’d set up for my audience. So the “Smartest Ape in the World” can say things that the dumbest professor in the world can’t!

Nobody’s going to confuse the speaker or the characters in the poems with me; that was the key. And this is what’s governing the sonnets I’m writing now. Though they’re on biblical themes, I’m essentially continuing the same project. Instead of looking at the tabloids in the supermarket, I’m reading and rereading the Gospels and wondering what the person in this or that situation would say. It allows me to explore all these voices and perspectives that the confessional mode didn’t allow.

TOJ: I love that you began that departure in the extreme by inhabiting some of the most bizarre voices available.

JL: Well, some of the voices I hear in the Gospels are pretty bizarre, too!

TOJ: The trajectory of your writing career includes several of these departures from the norm—not only in Tabloid News, but also with books like Standing Ground: A Personal Story of Faith and Environmentalism, which is not simply a collection of essays but an extended record of action and contemplation in light of events that took place in your community. What is the story behind that book?

JL: It’s connected again to that metaphor of at-one-ment. What occurred was that in late ’89 and early ’90, a federal law was passed requiring states to accept ownership of all nuclear waste generated in the state and to provide a place of disposal. New York State decided that they would build a nuclear dump, and the three sites chosen as the finalists in the selection process were all here in Allegany County. People in the community were, of course, disturbed. Everybody from far away, accused the community people of taking a “not in my backyard” stance. There was probably an element of that, but I think there was a larger issue of environmental justice.

There has always been a political element in my work; I think the metaphor of at-one-ment, as innocuous as it sounds, is quite political once you begin to apply it. I’d been doing a lot of writing on creation, on environmentalism, for lack of a better term, and I became involved in the expression of concern in the community. Eventually I became an advocate and practitioner of civil disobedience. Though I kept a pair of wooden shoes my father brought back from Europe after WWII on my desk during those days, I never rose to monkey wrenching.

About the same time these events were taking place, the Chrysostom Society, of which I’m a member, contracted to do a book called Stories for the Christian Year. Being a perfectly good Protestant with a most superficial understanding of the Christian year, I offered to do Lent. My idea was to journal on the relationship of faith to the creation for the forty days of the season. It turned out that this corresponded to the period of greatest intensity of the nuclear waste protests. I was journaling on it daily. When I was done, I wrote a 5,000-word excerpt from that journal for the Chrysostom book. Virginia Owens read the complete journal and thought it should be a book, and fortunately, Bob Hudson at Zondervan thought so also.

TOJ: That’s interesting in terms of shedding light on the role of the writer, in part, as the voice or conscience of the culture.

JL: Perhaps the most moving incident of that time came toward the end of the action. One of the people with whom I had worked said to me, “I envy you. Your faith has given you something I don’t have: images and metaphors to talk about these concerns.” He also gave me a T-shirt that said, “Nuke a gay baby seal for Jesus.”

TOJ: There are several new books on the way. One is your new collection Recluse Freedom. What has gone into this collection?

JL: It has twenty years worth of poems in it, more than any other book of mine, so it’s diverse. But I think it’s an accurate reflection of this whole movement of understanding the spiritual ecology we’ve been talking about. The opening section is a long poem, “Writing Home.” I began it about 1990, and it is part of the most confessional section. But it’s moving, formally, into blank verse and into a more abstract way of talking. In it I’m trying to articulate “home” narratively. Then there’s a section of prose poems that alternate with very formal, repetitive lyric interludes. I wrote them when I was teaching in the Adirondacks. They’re an exploration of being out of place while still exploring connections with the world; they’re a counter to the first poem. The last section of the book, what I call the Flat Mountain Poems, is the section that excites me most. Flat Mountain is that place where the temporal and the eternal intersect. It’s a place that is nowhere and everywhere. The section is a very deliberate exploration of the spiritual ecology, and it is much influenced by the reading of Chinese poets.

So, the book begins in my original voice; the prose poems bring in invention, a little bit of fantasy, and a more varied, less personal voice; and by the time we get to the Flat Mountain Poems, I cannot be trusted. There is a figure in the poems wandering around who has done some of the things I’ve done and who does things I would like to do; but it’s a fictive figure.

TOJ: You also mentioned working on a series of poems on the seven deadly sins written with two other poets. Could you describe the process that you, Jeanne Murray Walker, and Robert Siegel have engaged in collaboratively writing that collection?

JL: This was Bob Siegel’s idea. Bob and Jeanne were both at Houghton for the Writing Festival, and while Bob and I were off walking in Letchworth, Bob suggested we write a collaborative poem. We decided that the seven deadly sins would be fun to explore in a series of letters we would write to each other. On the way to the airport, Jeanne and Bob decided that Jeanne should be in on it also. I wrote the first poem to Bob, in which I rambled on in general about sin. He wrote a response to that and sent the two to Jeanne, and she wrote a response to them. Then we launched into the seven particular sins—we’ve since cut those first three poems, but they were necessary to get into the project.

I see the poem much from the perspective of my reading of Pope: a kind of verse essay, an ability to talk about all sorts of things, to go anywhere. It’s kind of a kitchen sink poem—you just toss into it whatever comes into your mind the way you can in a personal essay. They are mostly written in loose blank verse. But how do you hold together a long poem? What formal elements are necessary? As I’m revising it, I’m putting the sections I didn’t write in blank verse into blank verse, trying to make it a little more formally unified.

What’s curious, of course, is that if one person makes a change, it affects the next person’s poem, so I don’t know if we’ll ever finish it. Maybe it won’t be until we’re all dead and an editor straightens it out! We keep making changes, then we have to make another change in response, and we’re trying to do this on three people’s schedules.

It has been very important to me to be involved in this exchange with two poets whom I learn so much from every time I hear from them. Since I’m no longer traveling and getting out like I used to, it’s been lifesaving to be involved in this. Working on it has also had a profound effect on my perception and understanding of sin.

TOJ: A recent issue of Comment magazine is called Letters to the Young. It features a series of essays in which writers, artists, critics, pastors, and others offer wisdom to their counterparts at earlier stages within their respective callings. What would you say in a letter to a young writer of faith?

JL: I’m increasingly reluctant to say much to the young writer. But since you ask, I guess I should venture something. My experience is that faith allowed me to take risks in life and writing that I wouldn’t have taken otherwise. It allowed me to live largely outside the core of the literary world and to become a writer I never would have become had I followed the instincts I had during my graduate program and in my early publishing.

It’s not an experience that’s totally positive; there’s a great loneliness to it. But there’s something profoundly good about that. It forces one to live in hope, not expectation. It allows one to realize—at least some of the time—that what matters is the work working in you and leading you forward, not the successes, the publications, the prizes, to realize that you, in fact, are part of the work you’re writing.

[audio:https://theotherjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Waiting-for-Rain-1.mp3|titles=Waiting for Rain by John Leax]

Waiting for Rain I Remember Three Old Poets Who Wandered the Slopes of Flat Mountain in My Youth

In the afternoon wind the leaves turn

their pale undersides to the sky thickening

with clouds. It will rain by evening.

I walk slowly, easing my way

with the old stick that has let me

softly down many mountains.

Nothing pressing, free in the plenty

of time, I find my mind drifting

to thoughts of three old poets

who were bread and wine,

a sweet communion to my youth.

Each is gone, and I am old.

The first raised me from failure,

the second set me free,

the third gave me a snowy owl

and left a rifle in his will.

It never came.

The first discovered winter

a vast white emptiness, and cursed

the hope that bound us from the start.

He threatened pills but mercy

struck him by surprise.

The second disappeared without a word.

The third learned chaos,

raged against the loss of name

and place and died uneasy

week by week then day by day

before the hour of forgiveness

covered him in sand.

I give thanks for my old stick,

its polished knob and thorny spikes.

It bends a bit under weight

but it holds me up

as I bear these three through the wind-tossed

afternoon. I’ll carry them awhile—

as far as heaven in my prayers.

[audio:https://theotherjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Walking-the-Circuit-1.mp3|titles=Walking the Circuit by John Leax]

Walking the Circuit around the Cornfield I Walk Every Day, I Glimpse the Nature of Creation and Submit to Joy

Beneath the intermittent buzz of cars

spinning down the two-lane,

of trucks rumbling home,

the constancy of water falling to the river

lives, a rocky song rising

over the silent corn.

In summer air the tassels are still.

Gnats swirl in the sharp light,

a constellation of dark amazements

turning about a moving center.

Though all creation groans,

the movement of the leaves

in the tallest cottonwoods

betrays the presence

of the wind:

the love that calls each moment forth

desires gnats and corn

and walkers blessed with ears and eyes.