Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of three reviews on Terrence Malick’s latest film.

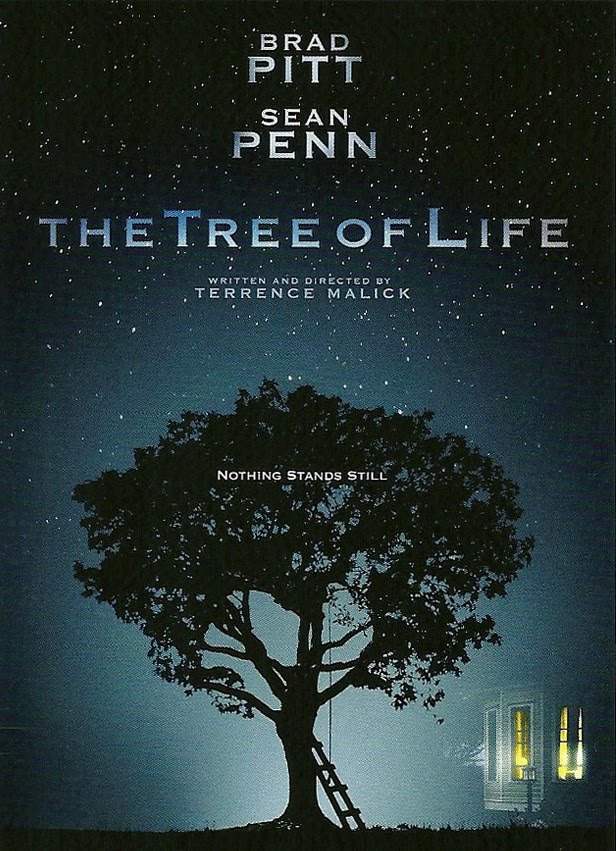

In reviewing any new work, particularly one from someone as storied and reclusive as director Terrence Malick, upon whose oeuvre critics tend to either lavish praise or shower derision, one has to gauge the newest constellation against the firmament of the back catalog. So it comes as no surprise that virtually every available critique of Malick’s most recent opus, The Tree of Life, contains at least some reference to his past work—a decidedly abbreviated category composed of four films—along with a mixture of biography and legend concerning the man himself.

What’s somewhat anomalous about The Tree of Life is the film’s ability, along with Malick himself, to crack the veneer of supposed objectivity and dignified remove that most critics try to maintain. There is something about the films of this utterly shy auteur (he didn’t even show up to the press conference at Cannes where the film premiered, eschewing the red carpet for the briefest of appearances at the tail end of the film’s screening) that makes film lovers salivate. In light of The Tree of Life’s abstruse and at times aggravating nature, the largely positive reception it has enjoyed seems to indicate a wave of enthusiasm that was predetermined, even before the film finally rode into the light after years in the editing room.

I’m referring not only to the tsunami of hype generated by the ambitious PR machine at Fox Searchlight, but also to a groundswell of good old-fashioned anticipation, a surfeit of good faith built up over Malick’s forty-year career and stoked by the assumption that a work labored over as long as this one (legends of the director’s fastidious work ethic in the editing room abound) must be worth the wait. We’re not dealing with an “Emperor’s New Clothes” scenario—the film has its merits to be sure, but it seems that those of us familiar with his work were predisposed to find them.

Some critics have turned a blind eye to their own inability to parse The Tree of Life’s dense thickets of philosophical overgrasping. But their best efforts at justification can’t mask the lingering disappointment. I get it; it’s hard to bag on a legend. Having for the better part of a decade cited The Thin Red Line as my favorite film of all time, I can empathize with anyone who wanted The Tree of Life to surpass anything Malick had ever done.

The New York Times’s A. O. Scott likens Malick to Herman Melville (May 27, 2011). He then tempers his own suggestions about how the film might have been improved by implying that had Melville taken the advice of those who might have tightened up some of Moby-Dick’s exploratory rambling, the author would have ended up lobotomizing one of the most treasured jewels in American letters. Scott concludes that even though some viewers (himself included) won’t be able to appreciate everything in the film, that’s OK. After all, he says, “The imagination lives by risk, including the risk of incomprehension.”

In fairness, it must be said that any analysis of The Tree of Life should qualify its critique in light of the fact that Malick is clearly attempting a different kind of film this time around. His watermarks are all still there—the whispered voice-overs relaying characters’ inner monologues, the flawless execution of period details, the infatuation with the natural world and with light, the stunning cinematography. In addition to these common threads, though, Malick’s past films have all been tied together with, and maintained internal consistency by means of, the presence of a much stronger narrative than what’s offered this time around. Badlands detailed a killing spree; Days of Heaven was the story of a man running from a murder charge, with his lover and little sister in tow; The Thin Red Line depicted the US infantry’s advance across the island of Guadalcanal in World War II; and The New World followed Pocahontas and John Smith as they yearned for one another across a great cultural divide. Each of these films features ambiguity, yet while they all have moments of opacity, you’re never truly lost, never left waiting all that long while to see what happens next.

In his latest epic, Malick incorporates all the challenging elements of his previous work while neglecting to deliver the kind of sufficiently arcing narrative that allowed his loose aesthetics to cohere in the past. You’d have to get up pretty early in the morning to avoid acknowledging the sheer power and beauty of Malick’s vision as channeled by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, but alas, pure beauty cannot substitute for the development of characters. This is not Koyaanisqatsi or Baraka, films that let the audience know from the get-go that they can kiss a traditional narrative structure good-bye. Malick sells his viewers something of a false bill of goods, leading them by means of certain conventions, particularly in the film’s opening act, to believe that they are watching the kind of movie that will actually go somewhere. It does not, and neither the film’s ambition nor the manifest sincerity of Malick’s grand gestures entitles him to a free pass on the sluggishness of a stalled plot.

Lubezki has been quoted as saying that Malick was less concerned with narrative than with creating a feeling—something akin to the rush of emotion conjured by a long-forgotten scent or a snatch of music. There are indeed many feelings we’re left with as the film jumps between modern day skyscrapers and mid-century Texas, one of the more predominant being angst.

Young Jack O’Brien, wonderfully channeled by Hunter McCracken, is torn over his relationship with his stern father and acts out accordingly. As a grown man we find Jack still adrift. The unmoored frustrations of his childhood, his ambivalence toward his father, and the death of one of his brothers have left him haunted and confused. A sense of forlorn hope permeates his character.

Malick’s choice to set his story in a quiet corner of Waco, Texas, during the mythological golden years of the 1950s, replete with a summer swimming channel, green fields, rope swings, and kids walking safely down the middle of sleepy streets, allows him to juxtapose the idylls of childhood with some of life’s most brutal realities. The images of the O’Brien boys riding their bikes through tall grasses will trigger untold memories, yet there is so much angst in the mix that the yearning gets choked out.

The Tree of Life stands in stark contrast to period pieces like Stand By Me or The Sandlot, nostalgic paeans set in the same slice of twentieth-century American history. We don’t pine for the lost innocence of childhood while watching this film—there’s too much trauma, confusion, frustration, and violence in the O’Brien household to make us want what they’ve got.

This is intentional. The death of Jack’s younger brother R. L. thrusts the eldest son and his parents into a struggle pitting the security and comfort of all that a white picket fence promises against the encroaching darkness of death and grief. Soon after learning of her son’s death, Mrs. O’Brien begins to question God.

Where were you? Why did this happen?

It’s at this point that Malick makes his boldest move in a long career filled to bursting with them. He undertakes a cinematic portrayal of God’s response to Job, that most famous of beseechers. The film segues from suburban Texas straight into a twenty-minute montage detailing the creation of the universe and the genesis of life on Earth. Galaxies spiral, cells multiply, dinosaurs graze, all of it overlaid with a soaring aria. The images are gorgeous, the allusion unmistakable; God did not deign to answer Job save to ask his own question, “Were you there when I fashioned the earth?”

One of Malick’s greatest strengths has always been his ability to grapple mightily with giant issues and tackle cosmic questions while paying no heed to the danger that his films might be thought pretentious. Ignoring the potential uncoolness of earnest passion has served him well again here—against all odds, the creation epic does not come off as cheesy or overwrought. Instead, we’re left pondering the great mystery of theodicy: how can a God who allows bad things to happen to good people be truly omnipotent while also truly good?

Part of Malick’s genius lies in his uncanny ability to telescope the viewer’s focus in the blink of an eye, moving deftly from universal themes to images that remind us of our individuality and back again, straddling the divide between the infinite and the mundane. At one point in The Thin Red Line, the focus jumps from a large battle scene to the pitiful struggle of a chick trying to hatch from its shell after falling from a nest, pivoting on a dime from the struggle of empires to that of a single, transient living thing. The shift in the moment that the creation montage begins, from the heartache of one woman to the origins of the cosmos, is one Malick will never top.

After the interlude ends we are returned to the O’Brien household of a decade earlier, its occasional joys and outbursts of rage captured in glimmers and hints. Malick has no equal in his ability to bend film to the task of evocation, and my complaint is not that he fails to deliver beautiful images, or even to reach the emotional lodestones he is digging for. Nor is my quarrel with his choice of questions, as those he asks are some of the most primal of all.

It is not for lack of heft that The Tree of Life falters but for want of mechanics. The plot, the frame to which all this beauty has been welded, is held together with flimsy string where it should be bolted. The images are incandescent, the themes endlessly resonant, the characters all rendered in fine detail, but things move so slowly and with so little resolution that by the end of the film one feels bludgeoned by endless lovely pictures.

Rather than using redaction and ellipses to great effect as he has in the past, drawing our mind’s eye to what is not visible by means of implication and allusion, Malick gives us a sketch of the O’Briens which remains only that. We see that Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien have a tense relationship punctuated by different parenting ethics. Mr. O’Brien tries to inure his sons to their natural aversion to violence through impromptu boxing lessons whereas their mother offers unconditional love. He rips the covers off them in the morning whereas she playfully holds ice cubes to their feet. Their stances face off across life’s ultimate division, delineated in the opening minute of the film as being composed of, “the way of nature and the way of grace.” But for all this, we never get more than a brief snapshot of the family’s larger story.

When asked to feel for Jack as a depressed adult who can’t move forward, our hands are tied. How has Jack’s relationship with his father changed in forty years? What has his mother done with her grief? How has the death of R. L. affected Jack’s relationship with his other brother, Steve? It wasn’t Malick’s intention to answer these questions, as stated by his cinematographer and evidenced by his film, and there’s a lot of gristle to chew on without bringing them into play. The problem lies in the director’s implicit request that we become invested in a family we see frozen under glass.

There’s an irony present in the indisputable complexity with which the characters are painted—Mr. O’Brien, with his evident love at odds with his forced, awkward displays of tenderness; Jack in his grief and longing; Mrs. O’Brien in her suppressed anger and incarnate grace. None of them are flat. The problem is that they don’t change. We ascertain their basic roles and the disposition of their characters within minutes, only to wait with increasing impatience as their imperfections and luminescence are fleshed out for two long hours during which the story refuses to move forward.

No filmmaker, no matter how great his talent, is above the responsibility of sustaining his audience’s interest if that filmmaker chooses to make a movie that feels on a visceral level as if it should be going somewhere. For all its lambent glory, all the evocative power of its characters’ longing, The Tree of Life fails to achieve what it might have had its undeniable power been given a full head of steam and allowed to run upon the clarifying rails of a more discernible plot.