On September 11, 2001, I was in an early morning seminary class when an administrative assistant came and told us that the first of the towers had collapsed. The class put down John Locke’s The Reasonableness of Christianity—after all, nothing seemed reasonable in those hours after we heard the news[1]—and spent the day talking on the phone with loved ones and watching CNN. My life in college and seminary had not been free of suffering—I had started and led a homeless advocacy group in college, worked at a camp for children with developmental needs, and lived in a house in which I occasionally found the homeless sleeping. But 9/11 exposed all these engagements as decidedly one-sided encounters with suffering on my own terms; it thrust me into the uncomfortable place of having to say something, to be a witness to God in the midst of disorder and chaos.

In the weeks that followed, churches struggled to minister to the families of the dead and traumatized while simultaneously describing what to do next. Some Christians responded with words of vengeance and others responded with patience. Intervarsity International Student Ministry recommended compassion for the dead and apologetics against Islam. Others focused on the mystery of evil, calling for Christians to stand with the broken in the midst of their suffering. And still others described the event as a judgment upon America’s moral failures.[2] That 9/11 impacted both Christians and their non-Christian neighbors is reflected in the complicated responses which have emerged since then, even as these reactions have not all been of one accord.

If the 9/11 attack upon New York and Washington were simply an attack upon the church, the question of how to respond would be decidedly less complex. Christ, after all, teaches disciples to turn the other cheek, to give to those who ask, and to pray for those who persecute them. But with regard to how Christians are to minister in times in which the church is not the direct victim of suffering, things become more complicated. What, then, is required of Christians who wish both to minister to their neighbors—those who are suffering—and yet and also bear witness to the call of Christ, a call to suffering? What, in other words, might it look like for members of the body of Christ to bear visible witness to a Christ whose life has overcome death in the midst of suffering and disaster, doing so not as American Christians, but as Christians living in the United States?[3]

In what follows, I hope to lay out one of the fundamental ways in which Christians bear visible witness to Christ’s call and stand with their neighbors who are suffering: repentance of our failure to witness to Christ’s person and work. Only through an ongoing process of repentance for our failures of language and deed—of calling out for blood instead of patience—can Christians properly bear witness to the Christ who has suffered with us and for us, and who transforms death into life.

* * *

In naming repentance as essential to Christian witness in light of September 11, I mean not only turning away from past acts of unfaithfulness in our speech—speech that ignores Christ’s call for forgiveness of our enemies—I also mean repentance as a persistent state which undergirds the Christian life, a continual surrendering of our individual, corporate, and institutional lives to the Spirit. For Christians to be able to stand with their neighbors in the wake of unspeakable terror requires first remembering on what basis Christians stand with their neighbors, and more fundamentally, it requires continual repentance from those modes of witness, habit, and exercise that bear witness to another Christ than the Christ who has suffered and overcome death. It would be too simple to call many of the responses to September 11 reactionary; rather, they were funded by particular understandings of who Christ is, what Christ has done, and who the church is to be. Some Christians forget the reconciliation given them in Christ, a reconciliation that binds them to the world without being of it, and this forgetting leads to total identification with national sentiments of vengeance in times of disaster. Likewise, other Christians take this reconciliation to heart, describing Christ’s work as a movement internal to the liturgical life, and thus withdraw from their neighbors in times of disaster, or at best, proclaim Christ at arm’s length. In times of national trauma, neither response bears witness to the Christ who was crucified and resurrected publicly and whose churches exist alongside—and not in isolation from—their neighbors.

To call for repentance is to thus call for two things.[4] First, it is to call for Christians to remember that in order for us to bear witness to Christ, we must first be conformed to Christ; to be repentant is to recall that we can only bear witness to Christ as we receive that reconciliation of Christ. Second, a call for repentance is a call for Christians to tell the truth about who Christ is and about who Christians are called to be. We are called to bear witness to the Word made flesh and what he has done, the one who has suffered with and on behalf of humanity, who has reconfigured the meaning of death, and who calls the world through the church to new life. That is not to say that we do this perfectly, that we should speak out of a false humility, or that Christians are the only ones who can stand among the suffering, but to say that the church cannot offer true witness or true comfort to its neighbors apart from repenting of its failure to rightly confess Christ.[5] We must acknowledge that our witness to God has been faulty, misguided, and halting. We must acknowledge that there have been times when we have borne witness to another Christ than the one who suffered and bears those wounds even in the resurrection. We must acknowledge that our speaking has often perpetuated violence rather than borne with the suffering and that we have often leapt to offer counsel without first undergoing the purification that makes our Christian witness possible.

Recovering a discipline of repentance will enable Christians to testify to the one who has suffered and overcome death and to thereby stand with Christ as he stands with those who suffer.[6] But why repentance? Why not emphasize the truth that Christ has overcome death, sin, and social division? In short, I emphasize repentance because Christian individuals, corporate bodies, and institutions are prone to witness to a God made in our own image, and in doing so, we are bearing witness to some other Christ than the Christ who suffered and died alongside us, on behalf of us, and—more hauntingly—because of us. In the absence of repentance, our proclamations of Christ’s wonderful yes, his embrace of the world and all who are brokenhearted, tends to become a vision of the church’s self-sufficiency. And so, as Karl Barth suggests, that yes of Christ must be accompanied by a provisional and chastening no to all of the ways in which our proclamation falls prey to idolatry.

With the ten-year anniversary of the 9/11 attacks behind us, it is important to recognize both those times when the church has witnessed well—standing with those whose lives have been shattered and calling on Christians to forgive those who perpetuate violence, even as those original acts of violence have begotten new violence—and witnessed poorly. And then because the act of witness is never finished, we must follow through with what we learn, striving always to bear witness to our need for repentance from misnaming Christ and our need for God’s grace.

The Repentance of the Individual

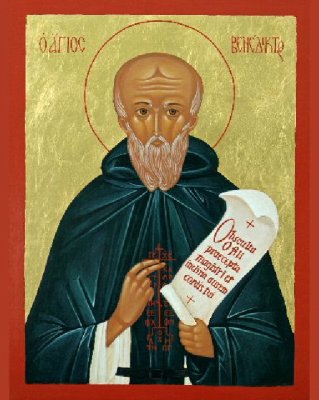

The easy way to dismiss Christian failures of witness after 9/11 is to attribute such failures to a few individuals rather than to the church catholic. These big names certainly get the press, and so shifting the blame their way is natural enough. But the more prominent failures direct us to the fact that—although Christian failure takes a number of forms—it is always individuals within institutions or groups who fail, who speak poorly, and who must ultimately confess before God. Although excessive focus on individual sin can (and has) led to notions of the church not as a body but as an aggregate of individuals, sources as diverse as Benedict’s Rule and Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Life Together acknowledge that corporate disciplines are done in conjunction with attention to the individual. Formation as a part of the corporate body of Christ occurs, as Benedict reminds us, through attention to the ways in which our individual fears, anxieties, and attempts to steer the world have gone astray.[7]

In Life Together Bonhoeffer counsels that “only those who are alone can live in the community,” that only those who have come to terms with having been “singled out by God” understand the gift of fellowship with others. Without solitude, we “plunge into the void of words and feelings,” but when we are “silent before the Word,” we learn to better align our speech to God’s will and the gift of his reconciliation; we learn to speak God’s word at the right time.[8] That is, unless we learn how to be silent and how to attend to our own words and language, bringing ourselves in line with the witness of Scripture, the collective language of the church will become a vacuous blathering. On the other hand, when we are confronted by the reconciling and patient Word of God, we are invited to repent of the moments in which we have spoken loudly and wisely from our own self-centered perspectives, to set down the mantle of “defender of the faith,” and to walk humbly with our God.

If we fail to pass through the purifying fires of individual repentance, of having our lives turned upside down by the Word of God, two things happen. First, the church’s corporate language becomes a sounding gong, speaking together the wrong thing at the wrong time. In this way, we come to amplify individual disorders in a corporate mode and to parrot the popular patriotism of the political cult. Second, the gathering of the church together further corrupts the individuals within the church rather than bringing those individuals healing. Thus, although individual repentance is not a substitute for the church’s collective repentance, it cannot be ignored if the church is to collectively speak anything about Christ’s overcoming of death in public. As individuals stand before God, receiving God’s judgment and forgiveness, they are able to stand with those who suffer, bearing witness to the God who they themselves know to be “for us” the God who has come for us in our death and suffering.

In an era when any response to 9/11 can be broadcast by means of social media without editing or reflection, Bonhoeffer’s words cut deep against contemporary necropolitics. Rather than empowering individuals to be a part of a politics of Jesus, these politics of certainty and retribution—sans the chastening act of repentance—speak of receiving the good news of Christ in its proclamation, but without any recognition that the gospel itself is a judgment upon our speaking of God, a judgment that enables us to speak truthfully. Thus, for Bonhoeffer, individuals must learn to be present before God’s reconciling word so that they might join together into a mighty chorus of witness rather than a maddening mob calling for vengeance.

The Repentance of the Body

In turning to the corporate aspect of repentance, the theologian L. Gregory Jones suggests that “forgiveness is a sign of the peace of God’s original Creation as well as the promised eschatological consummation of that Creation in the Kingdom, and also a sign of the costliness by which such forgiveness is achieved.”[9] Here, Jones draws together two aspects of corporate repentance. First, he notes that the forgiveness of God is received by the gathered church as the work of Christ. This is to say, that any act of repentance which we undertake as a church is only possible because of the prior work of Christ—in the creation of the church, Christians are gathered together only because of Christ’s reconciliation. But second, and equally instructive, is Jones’s counsel that the forgiveness given in Christ is understood within the context of God’s intention for the whole of the cosmos. The church’s reconciliation is understood not as its own possession, but as a sign of what is promised and meant for all creation. As such, the church’s repentance is connected to its mission to bear witness to the world; the reconciliation of the church is, in other words, the foretaste of God’s intent for all the world.

Many pundits, thinkers, and ordinary folk have noted that 9/11 drew America into the reality of the rest of the world. And in this respect, they are not far from the truth. But Christians in America should not have been looking for something else to connect them to their neighbors because the church’s reconciliation already speaks of its connection to the world—the repentant church is a light to the world, bearing forth the reconciliation of Christ, who embraces the world’s suffering in order to overcome it. In short, the church’s repentance leads it into the world and toward its neighbors. And in this role, the church serves as a foretaste of the “new humanity”; the life of the penitent and reconciled church exists as an image of the Christ who was sent to save the world.[10]

As Bonhoeffer saw, repentant individuals find their reconciliation with others in Christ; they find their reconciliation not as they withdraw from the world, but as they are drawn together into the world. Likewise, the corporate life of the church is one of mission into the world, a mission that through Christ’s own suffering and forgiveness joins with the suffering of the world. But the church can only do this by repenting of not being this body—by confessing that it colludes with power, ignores its Lord, and dismisses its calling. Only in repentance can the church offer a true word. As churches continue to reason together about what it means to live as the body of Christ in a world broken by acts of violence and terror, they must remember that they are drawn together and reconciled by the Christ who is sent for our healing and that we must follow our Lord into the world of suffering and violence as ambassadors of reconciliation.

The Repentant Institution

It is not enough for repentance to be a matter of the interior self or of the corporate body, however, because Christian faith is characterized not simply by the commitment of individuals but also by the institutions that aid individuals within their corporate organization, institutions that organize their relations and activities in offices, practices, and habits of doctrinal discernment. To describe what it might mean for the church as an institution to repent, I now turn to one of twentieth-century theology’s lesser known lights: William Stringfellow. To be sure, Stringfellow was not the only one to meditate on the capacity of institutions to function as a “power and principality,” but few wrote as provocatively and prolifically on the topic as Stringfellow.[11] By “institution”, I mean in many ways what Bonhoeffer did, in describing a community as having entities that exist over against the community—its codes, statutes, and organizing structures.[12] But as Stringfellow highlights, these entities often take on a life of their own, operating as a “power” rather than as an aid to the church.

Stringfellow worked as a lawyer in Harlem for a large part of his life. He was a self-taught theologian who worked for a time at the East Harlem Protestant Parish before becoming disenchanted with its bureaucracy. After leaving the employ of the church, Stringfellow used his legal skills to defend several notable ecclesiastical dissidents, including James A. Pike.[13] Stringfellow’s description of the value of church institutions is too complex to be undertaken fully here, but it can be summed up in this way: if the church is best described as a gift of God that can only happen as a consequence of Christ’s self-giving and the Spirit’s irruption into the world, then the ways in which the body of believers exhibit this gift to the world must mirror the manner in which the gift is given.[14] In other words, if Christ has called a new body of witness, this body must express itself in its institutions and order in ways that are commensurate with its calling. For Stringfellow, this included a willingness to revisit institutional proclamations that had been unfaithful and naming them as such, as well as an openness to the possibility that the very structures which enable our witness obscure certain possibilities of proclamation, silencing certain words of the Spirit which God in Christ calls forth.

Stringfellow is not suggesting that faithful churches should jettison the concept of institutions—as a creaturely body, the church can no more do away with institutions than people can do away with their own bodies—but that churches carefully evaluate the relationship between institutions and God. We must remember that institutions are to be seen as dependent upon the active lead of God, upon the reconciliation of Christ, lest they become lords over against the church or impediments to the church’s witness.[15]

For the church’s institutions to follow through with the kind of repentance exhibited by the individual and by the body corporate, the church must be willing to acknowledge when its own structures have inhibited its witness rather than enabled it and when its habits have become idols more than gifts. To borrow the phrase of John Howard Yoder, the church must be willing to “loop back” through its history—not to discard that history or heritage, but to prune back those things which have overshadowed the Christ who suffered among us and who calls the church to suffer with the world still.[16] If the institutions of the church lead us to neglect the suffering of our neighbors or to reject the 9/11 perpetrators as irrevocably beyond the grace of God, Stringfellow’s concerns bear considering: institutions of thought and practice, as part of the created order, can lead Christians away from discipleship as much as they can lead Christians toward Christ, unless they too mirror the reconciliation and repentance that must characterize individuals and the gathered church.

* * *

The decade since the events of September 11 have presented more than a few opportunities for Christians to evaluate their personal, corporate, and institutional witness. Public proclamations that followed September 11 which emphasized vengeance rather than Christ’s suffering and resurrection must be repented of. But even as September 11 beget two international wars, damaged relations between Christians and Muslims, increased nationalism in churches, and blurred the lines of allegiance between Christ and country, the opportunity and need for repentance has only increased. Christians must remember that it is only by being forgiven that we can call for forgiveness, mercy, and reconciliation.

As we reflect on the decade of war and destruction that has prevailed in the wake of 9/11, I believe we must wrestle to hold together our witness of Christ’s suffering and redemption as well as a repentance of our failure to reflect this suffering and redemption. We must continue to proclaim that Christ suffered among and for us and that Christ now calls the church to bear witness to the truth that in him suffering is not the final word. And we must be willing to acknowledge the ways in which our witness has not been true, has skipped past repenting of our violence and our disobedience, and has failed to bear witness to the Christ of the resurrection. It is with this plea for repentance that I end, in the hope that the churches of America can be marked by their penitence, in order that they be known as witnesses of the truth.

This act of repentance is not one that can be done once for all time but one that must be a part of the ongoing practices of the Christian life. As the wars waged in the wake of the attacks of 9/11 continue to loom large in public memory, Christians are reminded that the legacy of moral failures is longer than we can predict. But praise be to God, the legacy of faithfulness extends beyond moments of seemingly pointless witness. May it be that in the years to come Christians may recover repentance in its individual, corporate, and institutional aspects; may the witness of the body of Christ be fulsome and ever renew the church.

[1] As Marilyn McCord Adams has argued, the presence of horrors such as 9/11 illuminate what Augustine described as the “non-sense” of evil—that evil, as the privation of good, ultimately cannot be explained or attributed to a single cause; rather, acts of violence and death that we might characterize as evil are a turning of the love of God into a perverted love of one’s self. See Christ and Horrors (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 42ff.

[2] For more on Intervarsity’s response, see http://www.intervarsity.org/ism/article/802 and George Weigel’s later book Faith, Reason, and the War Against Jihadism (New York, NY: Doubleday Press 2009). For more on responses that emphasize standing together with the broken, see Vincent Druding’s moving reflection, “Ground Zero: A Journal,” First Things (online) (December 2001), http://www.firstthings.com/article/2008/04/ground-zero-a-journal-6. For more on responses that perceived the tragedy as God’s judgment, see the interview with the late Jerry Falwell by Pat Robertson on the 700 Club program on September 13, 2001, http://www.beliefnet.com/Faiths/Christianity/2001/09/You-Helped-This-Happen.aspx .

[3] See 1 Corinthians 15:57, NRSV.

[4] In describing repentance, I am not thinking of Catholic penitential practices or Protestant practices of personal guilt and confession, but of acts that characterize both the individual and the church’s corporate life.

[5] See John Milbank, Theology and Social Theory (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 1990), 1.

[6] On this point, see Thomas Weinandy’s Does God Suffer? (Edinburgh, UK: T&T Clark, 2000), for a helpful exposition of how Christians have traditionally confessed that Christ embraces suffering.

[7] St. Benedict, The Rule of St. Benedict (New York, NY: Vintage Press, 1981).

[8] Bonhoeffer, Life Together/Prayerbook of the Bible, DBWE 5 (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2005), 82, 83, 85.

[9] Jones, Embodying Forgiveness: A Theological Analysis (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1995), 5.

[10] See John Flett, The Witness of God: The Trinity, Missio Dei, Karl Barth, and the Nature of Christian Community (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2010).

[11] Other notable voices in this twentieth-century recovery of the “powers and principalities” include Karl Barth, Oscar Cullman, and John Howard Yoder.

[12] See Bonhoeffer, Communio Sanctorum: A Theological Study of the Sociology of the Church (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1998), 42ff.

[13] See Anthony Dancer’s biography of Stringfellow, An Alien in A Strange Land: Theology in the Life of William Stringfellow (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2010), 81ff. For Stringfellow’s version of these events, see Stringfellow and Anthony Towne, The Bishop Pike Affair (New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1967).

[14] See Stringfellow, “The Church as Event,” Christian Scholar 40 (1957): 212.

[15] Ibid., A Second Birthday (Garden City, NY: Doubleday Press 1970), 145–6: “I do not denigrate institutionalism as such in the Church. I see, specifically in the account of Pentecost, that the Church’s peculiar vocation is as an institution—as the exemplary principality—as the holy nation. So ideas of a non-institutional church or a deinstitutionalized church or underinstitutionalized church seem to me to be as nebulous as the Greek philosophy from which such ideas come and contrary to the biblical precedent.”

[16] Yoder, “The Authority of Tradition,” The Priestly Kingdom (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984), 71.