Nothing affects us chemically like being in love—the sensation of floating on air; the hazy, dreamlike reality; the natural high. But just like withdrawal from any other drug, withdrawal from being in love can be hell. I was reminded of this last spring. The sun was out, the trees were in bloom, yet life stood perfectly still.

This girl did a number on me. She embodied Bob Dylan’s song “She Belongs to Me”—she had everything she needed, she was an artist, and she didn’t look back. One day while sitting in her apartment, she turned to me and said, “I think I need a break from relationships.” As it turns out, breaking up is, in fact hard to do.[1]

My friends weren’t that great at cheering me up when it happened. Happy little euphemisms about the quantity of fish in the sea fell on deaf ears. On the verge of what seemed like a lost relationship, I thought that the rare Seattle sun would improve my disposition. I was wrong. As I walked to the post office, tears brimming underneath my sunglasses, Dylan’s words came to me, from the song “Meet Me in the Morning” off his 1975 break-up album, Blood on the Tracks. In my mind, he sang, “Every day’s been darkness since you’ve been gone.” Dylan wasn’t making me feel that great either. No one wrote better break-up songs than Dylan, but their emotional message wasn’t exactly uplifting. It became clear that I needed a new source of advice.[2]

Crisis intervention specialists know when working with the depressed to investigate past ways those in crisis have coped with grief. For me this included drinking, sleeping, television, and countless ways of avoiding reality. As a child and adolescent I ran to my parents for comfort, but I’m an adult now and my parents live on the other side of the country. Attachment theorists tell us that when the mother is unavailable to provide comfort, the resilient child will look to the next closest person to be held, whether it is the father or a grandmother or a sibling. If the child can find security easily throughout childhood, it will develop the ability to mother itself. This includes regulating mood and affect. Without consistent attachment figures to provide us comfort and space to explore our worlds, we develop into insecure adults who respond to emotional stimuli by either over- or underregulating our emotions, whereas if we are secure, we have considerable psychological resources for mitigating loss, and these resources include an inner fortitude to search out healing connections with others. But how does this regulation of emotions happen?

In his book The Interpersonal World of the Infant, Daniel Stern notes that “early in life, affects are both the primary medium and the primary subject of communication.” Infant experiences are dominated by emotion. Anyone who has ever interacted with a baby understands this. The baby doesn’t comprehend that mother is in the next room; it only knows that it is frustrated. Our mothers, however, if they are good enough, help us learn through emotional connection and communication that everything will be fine when they leave the room, that it is, in fact, tolerable to exist without them. Through that relationship, we, as infants, experience a transition from co-regulation of affect to self-regulation of affect. This is a dynamic process that also leads to the mental representations of our co-regulators as well as “representations of interactions that have been generalized.”[3]. In short, if we experience a secure attachment that allows us the freedom to explore and to be affectionate, we internalize our mothers and thereby experience a secure mental base from which to explore the dynamic emotional world of ourselves and others.[4] Think of these representations as emotional memory- we remember what it was like to be soothed by our parents and we emotionally soothe ourselves. As adults, we take care of ourselves mentally in the same way that our mothers physically cared for us as infants.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that abandonment has to be fun, and on the sunny day in question, I was in need of some motherly co-regulation of my insecure affect. After Bob Dylan failed, I wondered about other artistic mood enhancers. Are there ways to find co-regulation through others who may not be present with us? Through music and film, or art and poetry? Scrolling through my iPod, I found my answer in Steely Dan.

* * *

Is it possible that listening to a digital facsimile of music recorded eight years before my birth by someone I’ve never met could trigger a self-regulation of affect? Neuroscience suggests that music can cause the same feelings we experience when being loved by our mothers. From a neuroscientific perspective, groovy music triggers the release of dopamine, one of the same neurotransmitters, along with serotonin, that is released when we feel loved. In his book This is Your Brain on Music, Daniel J. Levitin, a neuroscientist, audio engineer, and production consultant to Steely Dan, notes that listening to music causes a series of rhythmic activations in the mesolimbic system of our brains, which is involved in pleasure and producing dopamine.[5]

The process of listening to music is mediated by the cerebellum, which has dopamine receptors and is involved in producing pleasure and regulating affect through its connection with the frontal lobe of the limbic system, the emotional center of our brains. And so we experience a pleasurable response that travels from the ear to the cerebellum and then to the limbic circuit, and it even happens in rhythm with the songs we love.[6] Not only do we receive feel-good chemicals with feel-good music, we also receive them with a beat we can dance to! Combine this process with our feel-good memories of songs and we develop our taste, the songs that make us feel good.

Eating a tasty piece of bread or an entire pizza also triggers systems that produce serotonin and dopamine and I tried both after the break-up, to no effect. But as Donald Fagen’s voice washed over my auditory cortex, I was able to appreciate the sunlight and to think for the first time that things might actually get better. The soft rock classic certainly lacked the rush of shame that inevitably follows the consumption of a large Italian sausage pie, but more importantly, there is an affective quality to music that gives it more meaning to us and creates a more interpersonal experience. We don’t react to music in the way we react to bread, that is, unless the bread provides us with stimulation and hope as well.

Is it possible to have an interpersonal experience between two people who don’t know each other and aren’t actually speaking to one another? These encounters are what the Jewish theologian Martin Buber described as encounters with “spirit becoming forms.” Buber wrote about his own interpersonal encounters with the theater when he said, “It was the word, the ‘rightly’ spoken human word that I received into myself, in the most real sense.” Buber had an affective encounter with the play that was taking place before him.[7]

Religious worship is steep in these encounters. There is no better example of affect regulation in music than such hymns as “We Shall Overcome” or “It Is Well with My Soul.” Like a mother who honors the baby’s anxiety yet calms it down, these songs let us know that bad things will happen and we will survive. Just as Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel sing in the folk classic “Bridge Over Trouble Water,” “When evening falls so hard I will comfort you,” these songs identify our distress and steer us toward a more calm mental state, thus co-regulating our affect and re-creating the affective connection, like a mother soothing her infant. As Bob Marley explained it in “Trenchtown Rock,” one of the good things about music is that “when it hits, you feel no pain.” We are comforted by singing and being sung to. Some of us are spirited by Lady Gaga or the cast of Glee. I am comforted by Steely Dan.[8] Our relationships with music and with others are complex matrixes with infinite variables

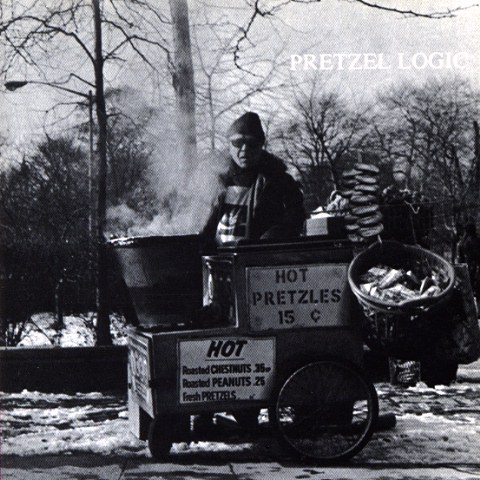

Some pop songs comfort us less like motherly presences and more like sardonic old geezers. Lifelong friends and songwriting team Donald Fagen and Walter Becker deal in the realm of existential angst, and although their characters often self-soothe with opium and hookers, the solidarity of the weary often shines through the seedy cracks of their narratives. Sometimes the tone of a Steely Dan song is like the chastisement of an older brother, like in the songs “Reelin’ in the Years” or “Gaucho.” Sometimes they feel like geriatric losers reminiscing together like in “Kid Charlemagne” or “Deacon Blues.” One gets the idea in listening to a Steely Dan record that Becker and Fagen may be more intimate with their drug dealers than their girlfriends, and it was exactly this kind of jaded camaraderie I desired after being rejected by an attachment figure. There is a sense when listening to Steely Dan of being joined—I was looking for solidarity when I put on Pretzel Logic, for someone who understood the straight male experience and could maybe point me in the right direction, like a child whose parents are absent and compensates by discussing his trials with an imaginary friend.

By the time Pretzel Logic came out in 1974, Steely Dan were familiar with trials. The team of Becker and Fagen had struggled with the music industry since the mid-sixties when they began their attempted first-choice career as songwriters. They had some small success, penning a single for Barbara Streisand, but for the most part, their songs were considered too complex to find much pop appeal. Eventually, they started their own band in order to showcase their compositions. Their style was unique, combining a postmodern musical pastiche of jazz, rock, Latin, and blues with untimely vague lyrics. When their first record, Can’t Buy a Thrill, came out in 1972, it contained two surprise hits, “Do it Again” and “Reelin’ in the Years.” By the time their third record, Pretzel Logic, came out in 1974, they had solidified themselves as consistent and prolific genre-bending pop songsmiths.

In contrast to other successful pop bands, Steely Dan wrote very few love songs, and Pretzel Logic is no exception. There is one song on this record about a woman, the androgynously titled “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” a plea by the unrequited Fagen to a woman who may or may not plan on calling him one day, but even here, Fagen is vainly detached. Still, Pretzel Logic gives an occasional glimpse of the void behind Fagen’s narcissistic shell and this, in the song “Any Major Dude Will Tell You,” is where my own affective connection with Steely Dan takes place.[9]

“Any Major Dude Will Tell You”[10] is essentially a letter from Fagen to a funky friend whose super fine mind has come undone. We aren’t privy to the impetus for the chaos, but we are informed that the friend’s world has been fragmented by loss. Fagen attempts to provide hope as he sings, “Any major dude with half a heart surely will tell you my friend / Any minor world that breaks apart falls together again.” But Fagen’s cheering up would ring hollow without his contingent response to his friend in the second verse, which he starts by asking, “Have you ever seen a squonk’s tears? / Well, look at mine.”

Donald Fagen isn’t the most handsome guy in the world, but he’s not the ugliest. On a scale from Lemmy to Elvis, he falls somewhere in the David Crosby territory. However, a self-comparison to the legendary folk creature, the squonk, is especially harsh. William T. Cox wrote about the squonk in his 1910 book, Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods. He described it as a creature that is so ugly that it only travels at night and weeps constantly. Its “misfitting” flesh is covered in “warts and moles.” When cornered by a hunter, the squonk would actually dissolve itself with its own tears.[11] And so Donald Fagen refers to himself as a squonk, a creature who is so painfully aware of its own brokenness that it can destroy itself in its tears. Fagen, the major dude of the song, connects with his friend by humbling himself, by letting go of his own defenses. In a very un-rock-star moment, Fagen lets his self-loathing shine in an attempt to join a brother in grief.

And yet he still sings that things can get better, that any minor world that breaks apart falls together again. There is something redemptive about hearing how small our worlds are, about being joined in our small-world grief, even if it is being joined by someone in our headphones. This is an affective connection with music, created by the rhythm, the harmony, and most importantly, a human being poetically confessing his humanity. Actual self-regulation of emotion is an illusion- our ability to soothe ourselves is an outcome of our ability to reach out to others even if they only exist in our memories or our headphones.

Of course, nostalgia also factors into our affective connections with music. For example, my father sings like ex-Doobie Brother Michael McDonald. This matters because the blue-eyed soul singer fashioned a career from singing back vocals on Steely Dan classics. And this matters because my affective coalescence can’t be explained by the just dopamine that Pretzel Logic causes to surge through my neural pathways. Songs can make us feel all kinds of emotions. It is the affective quality of “Any Major Dude Will Tell You” that matters and it is the internal representation of my father that Fagen triggers. But in the same way that the hymns we sing engage our mental representation of a figure that may or may not have anything to do with an actual deity, Fagen’s words of encouragement come to me like my father’s words of comfort as a child.

My sense of nostalgia with Pretzel Logic may or may not be because my father raised me on the music of Steely Dan and because he sings like a member of their crew. Music is a mystery and so is Steely Dan. As much as we know about the neuroscience of sound or about attachment theory and affect regulation, there is an unknown spiritual element to that movement within us when we listen to music. This is another reason that music is inextricably tied to worship. This is also why listening to ’70s soft rock is sometimes a spiritual experience: the utter depravity of Fagen’s lyrics and their near perfect combination with the sophisticated, aristocratic harmonies and production of Pretzel Logic exists on an unexplainable plane, a true intersection of our most immanent base conditions and the transcendence of beauty and knowledge.

* * *

Three days after my walk with Steely Dan, the girl I pined for informed me that she needed a break, not a break-up, prompting my interest in the neuroscience of overreaction. The rupture that caused me grief experienced was repaired over the course of a few days. I no longer had to rely on my iPod to cope with loss, and yet, traumas happen to us every day, some large and some small. Music helps us navigate these terrifying waters of attachment and loss, but nothing compares to the healing power of looking into the eyes of a caring Other. And while Steely Dan will be there when I need to cope with another loss, feeling loved does not compare to being loved.

A piece of pizza, a rock song, or a mound of cocaine are coping mechanisms. Some of these mechanisms are healthier than others, but they cannot replace true relatedness. They can only fleetingly take our minds off the absence and hold us over until the hunger or loneliness returns. This is what Fagen calls “time out of mind,” an escape from the anxiety of loss, a numbness to reality. But unlike drugs, art, like communion bread, can provide hope in its narrative and its neuroscience. It is this dual chemical and eschatological nature that makes music powerful and healing. It’s all in the chorus of “Any Major Dude Will Tell You”—when the demon is at your door, in the morning he won’t be there no more. Sometimes, we just need to hear it sung that everything can go back to normal.

[1]

<A HREF=”http://ws.amazon.com/widgets/q?rt=ss_w_mpw&ServiceVersion=20070822&MarketPlace=US&ID=V20070822%2FUS%2Ftheothejour-20%2F8014%2F09c13c33-3003-4c01-b48b-6e42a3bb4e41&Operation=NoScript”>Amazon.com Widgets</A>

[2]

<A HREF=”http://ws.amazon.com/widgets/q?rt=ss_w_mpw&ServiceVersion=20070822&MarketPlace=US&ID=V20070822%2FUS%2Ftheothejour-20%2F8014%2Fa5d7dae7-8bc8-49f8-9f67-6d8f271f002d&Operation=NoScript”>Amazon.com Widgets</A>

[3] Stern, The Interpersonal World of the Infant: A View from Psychoanalysis and Developmental Psychology (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2000), 132–33 and 97.

[4] David J. Wallin, Attachment in Psychotherapy (New York, NY: Guillford Press, 2007), 65.

[5] Levitin, This is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession (New York, NY: Penguin, 2006), 191.

[6] Ibid., 189 and 192.

[7] As quoted in Kenneth Paul Kramer, Martin Buber’s I and Thou: Practicing Living Dialogue (New York, NY: Paulist Press, 2003), 49 and 59.

[8]

<A HREF=”http://ws.amazon.com/widgets/q?rt=ss_w_mpw&ServiceVersion=20070822&MarketPlace=US&ID=V20070822%2FUS%2Ftheothejour-20%2F8014%2F2ae854fc-a97b-4a2d-8cf2-566ee65eb701&Operation=NoScript”>Amazon.com Widgets</A>

[9]

<A HREF=”http://ws.amazon.com/widgets/q?rt=ss_w_mpw&ServiceVersion=20070822&MarketPlace=US&ID=V20070822%2FUS%2Ftheothejour-20%2F8014%2F31914099-9cf8-4a8f-b841-09afb51685db&Operation=NoScript”>Amazon.com Widgets</A>

[10]

<A HREF=”http://ws.amazon.com/widgets/q?rt=ss_w_mpw&ServiceVersion=20070822&MarketPlace=US&ID=V20070822%2FUS%2Ftheothejour-20%2F8014%2F1eca5601-829a-4be7-850b-1854969ca5d7&Operation=NoScript”>Amazon.com Widgets</A>

[11] See Cox, Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods: With a Few Desert and Mountain Beasts (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2010 [1910]).