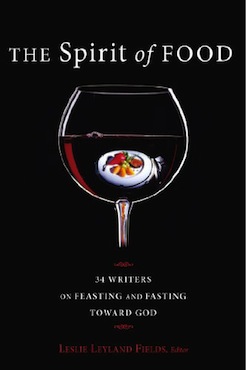

Editor’s Note: In 2010, The Other Journal published The Spirit of Food: Thirty-Four Writers on Feasting and Fasting Toward God, a collection of essays and recipes that colorfully depict how our acts of eating echo the community of the church and the sacrament of Communion. Now, as a companion to Gregory A. Boyd’s recent essay on the randomness of evil, we publish an essay from The Spirit of Food that meditates on the same tragic bridge collapse that opens Boyd’s piece.[1]

1

A bridge has fallen in the city where I live.

I was a thousand miles from home at the time, and my mother phoned to tell me about it. “There’s been a tragic accident,” her recorded voice said. “On 35W, the bridge collapsed into the Mississippi.”

My husband, two sons, and I had crossed that bridge hundreds of times. We back out of our driveway, drive east five blocks, and turn left onto the northbound interstate that brings us to the concrete and steel eight-lane span across the Mississippi River. We crossed it to go to work and visit friends, to get to soccer games, Dinkytown, the Loring Pasta Bar, and the East Bank of the University of Minnesota. And we crossed it to return home.

I played the message again.

2

My mother taught me to make Swedish pancakes in her kitchen long before I had a kitchen of my own. Each pancake is about six inches in diameter, lacy like a doily, in variegated shades of beige and brown like the meat and skin of an almond, and thin as a French crepe. My father, siblings, and I gladly kept the cold cereal in the cupboard on the special days my mother heated up her pan.

Swedish pancakes, topped with either lingonberries or maple syrup, are a special tradition now for my family also. The breakfast is anchored not to a particular holiday but simply to a chosen morning. One of us knows the time is right, says so, and the plan is set.

1

My twenty-year-old son was OK, my mother’s message assured me. My father located and talked to him before they called me. They didn’t want me to worry.

I dialed my parents’ number. “What happened?” I asked, hoping to hear that I had gotten it wrong. But no: at rush hour, less than sixty minutes earlier, the bridge simply fell.

Interstate 35 runs north-south across the United States, from Duluth on the west end of Lake Superior down through Minneapolis and St. Paul, where it splits temporarily into 35 West (35W) and East (35E), respectively, and on through Des Moines, Kansas City, Wichita, and Oklahoma City, finally ending in Laredo on the bank of the Rio Grande. It crosses, among others, the Minnesota, Missouri, and Red rivers, the Kettle, Winnebago, South Skunk, and Washita, the Frio, and Nueces.

Driving north across the 35W Mississippi River Bridge, from the river’s west to east banks, seemed no different than driving on any other expanse of freeway. The bridge ran flat from one river bluff to the next, like a Popsicle stick laid between two bricks, with no graceful arches or taut suspension cords to alert travelers to the deep moving water below. The bridge is set on the far edge of downtown, where the river curves south and the bluffs start their rise from its banks, fooling the eye traveling at fifty-five miles an hour into believing that the continuous scenery is all one frame without an ancient cleft in bedrock running through its middle.

But driving south on the bridge could take your breath away. Here the river curved toward the traffic, its bridges fanning out to the right: the Stone Arch, Third Avenue, and Hennepin. St. Anthony Falls crashed below. The city birthed on the Mississippi sprang up blue and glittering, reflecting sky and water in glass and steel.

2

The recipe for Swedish pancakes—“Arthur’s Favorite Pancakes”—passed from my grandmother to my mother to me:

2 eggs

1 cup milk

2/3 cup flour

Arthur was my grandfather. Born in 1900 in Nyland, Sweden, he moved to America at the age of twenty-three and settled in Minneapolis, where he married Jenny, my grandmother, who was also from Sweden. Arthur worked for the phone company and occasionally preached in his native language at a Swedish church with an immigrant congregation. When my mother was nine, three churches in Sweden asked Arthur to be their pastor, so the family boarded a ship and set sail. They planned to stay indefinitely, but then Nazi Germany attacked Norway, and they heard the gunfire near the border to their west. Yielding to the pull of U.S. safety, they recrossed the Atlantic and returned to Minneapolis.

I have an old family movie of Arthur, circa 1969, walking from my childhood home toward his car, a turquoise and white Chevrolet. He’s dressed in a navy suit, white shirt, and dark tie. A white handkerchief is folded into his breast pocket. His thinning salt-and-pepper hair is neatly combed. The coloring of his long face testifies to sunshine and good circulation. Jenny died a couple years earlier and he walks alone. As the camera follows him, he waves and smiles. He chuckles. I remember sometimes he laughed so hard he could hardly speak. His smile pulled his dimples in tight. His face taught me joy, as if it were my birthright.

1

“Mom, there’s sirens and smoke everywhere,” my son said when I called him after talking to my parents. He was downtown, walking toward the river.

Less than fifty minutes earlier, he had backed our car out of the driveway, driven east, and taken that north ramp onto 35W. He and his friend were on their way to see another buddy who lived in Dinkytown, just across the bridge. They had planned to leave about twenty minutes earlier, but the friend’s father needed a quick favor. Their original plan placed them on the bridge at about 6:05 p.m., the time it fell. Due to the delay, they approached the bridge about 6:25, but by then, the bridge lay in the river and the road was closed.

Stories like this were everywhere. A friend’s nephew drove south on 35W to cross the river, but at 6:02 he decided to turn off and take a different route. My sister’s coworker crossed the bridge at 6:04, felt the car shake, and thought something was wrong with her tires or the engine. When she reached the other side, she looked in her rear view mirror and saw the bridge drop behind her. Another coworker suddenly chose to forego the 35W Bridge and instead took the Tenth Avenue Bridge, just downriver, a route he never took. As he drove across that smaller, older bridge, he looked over and saw the interstate bridge fall.

2

To start, crack open the eggs and beat them, using a metal whisk, into a pale yellow slurry. Next, pour milk into the measuring cup and add this to the eggs. Whisk again. Finally, spoon the flour into the measuring cup, level it with a knife, and dump it into the egg-milk mixture. More whisking and then the thin batter of no more substance or color than melted vanilla ice cream is ready to cook.

There is more to making the pancakes than following the recipe. The recipe matters, of course, but its list of ordinary ingredients and simple instructions won’t show you how to move your wrist while swirling the batter in the pan or how to wait for the dancing water.

1

When the bridge fell, I was staying in a college dormitory in Santa Fe for a graduate school residency. An undergrad student in a dorm lounge sacrificed his televised baseball game to let me watch news coverage of the breaking story. Paula Zahn—on her second-to-last day at CNN, her first day being 9/11—showed viewers live pictures of smoke rising up from the river and an aerial view of the bridge missing from the line-up of its diminutive fellow bridges, like an octave without a middle C. I looked at these pictures as if a stranger, unable to orient myself to the shift in reality. I was accustomed to seeing my city at eye level, unblurred by smoke and settling dust.

Zahn reported people stranded on the span remnants, rescue boats in the water, and survivors being carried up the riverbank. The bridge’s middle span had dropped right into the water, its weighty fall causing a wind. The north and south ends, sheared off, hung at precarious angles. A school bus, full of children, stopped right at the edge of a downward-pointing span. A semitrailer burned next to the bus, and a railroad car lay crushed underneath the bridge’s north end. Police cars, ambulances, and fire trucks lined both sides of the river. Divers searched the moving water, but not for long, she said. Stormy weather was moving in.

Fifty to one hundred cars and trucks had been on the bridge at the time, a small number for rush hour. A witness suggested that resurfacing work on the bridge had limited its traffic capacity to one lane in either direction, and therefore, the number of vehicles was far less than on an ordinary Wednesday.

2

“Tell us about the miracles,” my sons often said to my mother when they were little, even though they’d heard the stories again and again. My parents used to travel from St. Petersburg, Florida, to Minneapolis to visit us, and they stayed in a makeshift guest room in our basement. Early in the morning, the two boys would run down the stairs and into their room. They jumped on the bed and slipped under the covers. Arthur starred in at least two stories.

In one of the stories, a teenaged Arthur was alone in the forest of Ångermanland, Sweden and had become trapped under a large rock. Unable to free his leg, he prayed and fell asleep. When he awoke, he found himself free and sitting on top of the rock. The mystery of how he got there sent giggles and goose bumps into my little boys.

The other story was less an adventure tale than a domestic tale. When the grown-up Arthur moved his family to Sweden, their family had little money. One day, Arthur had to take a bus and leave for a few days on church business.

“You can’t go,” said my grandmother. “We don’t have much food and the potatoes are gone.”

“But I have to go,” said Arthur.

He knelt on the floor right then and prayed for potatoes. “God will provide,” he said as he stood and went out the door. No sooner had he reached the gate at the end of their yard than the bus pulled up. The bus driver opened the door and lifted up a sack of potatoes. “A lady in town thought you might be needing these,” he said, handing the sack to Arthur.

1

Two days later and still in Santa Fe, I sent my son in Minneapolis a morning text message—“just checking in.” By late evening he still hadn’t responded. He usually texts back quickly, but he’s busy and worked long hours as a waiter, and there are all kinds of reasons why he didn’t respond, yet I put two and two together and came up with eight million and started to tremble inside.

What could have happened now? If a bridge can fall in the city where I live, a bridge he was nearly on when it fell, then anything can happen. Worry got the best of me and I called him.

He picked up within a few rings and said he was walking to his car on his way home from work. His shift had been long, the tips decent. He carried take-out food from the restaurant. I made light of calling him rather than waiting for him to call or text me, trying to cover my worry. No problem, he said.

2

My husband starts the coffee. Usually there is a Swedish brand or a dark French roast stashed away for just such an occasion. He inserts a white coffee filter into the coffeemaker’s brew basket and measures out the coffee, one heaping scoop for every two cups, although our sons encourage him, “Make it stronger.” He pours water into the top of the maker and presses the start button.

He turns on the television, flips through the stations looking for news, and then turns it off. Headlines won’t penetrate the next hour or two. Laundry lies silently in piles a floor below. A floor begs to be swept.

1

After talking to my son, I walked back to my dorm room, full of awakened nerves. I sat down at the worn wooden desk, opened my laptop, and played music from a CD of hymns recorded by a band of brothers I know.

“Come thou font of every blessing / tune my heart to sing thy grace / streams of mercy never ceasing / call for songs of loudest praise.”

Tremble: be still.

“Be thou my vision / O Lord of my heart / naught be all else to me / save that thou art.”

Throat, tight and dry: gulp life like a baby’s first breath.

A Quaker hymn played last. “The peace of God restores my soul / A fountain ever springing.” I hummed, then sang, so very quietly. “How can I keep from singing? / How can I keep from singing?”

Was it the words affirmed over centuries of collective history and decades of my personal history? Or the familiar melodies? The guitars and harmonica and voices in harmony? Artistic beauty, wrote philosopher Jacques Maritain, slips light into the mind without effort.

Heavy heart: run away in joy.

2

On each side of the rectangular birch table, I place a heavy Fiestaware plate: purple like concord grapes, navy like lapis stone, cornflower blue like the morning sky, and orange like poppies. I often skip a tablecloth or placemats because I like the look of the colors on the light wood palette. I set out coffee mugs in a mix-match style: orange with navy, cornflower with purple, purple with orange, and navy with cornflower. The table explodes color like newly opened watercolor paints.

Silverware comes next. My left hand wraps around cool stainless steel while my right removes a knife, spoon, and fork from the cluster to place at their respective sides of each plate. I fold four green napkins and slide one under each fork. I set out a white china pitcher filled with cream. A small rectangle of pale yellow butter goes on a china dish. A white bowl holds sugar cubes. Two blue candles stand lit in crystal holders.

My mother served the pancakes on china plates, all white like a canvas on which to stroke and drip the red-violet paint of lingonberries. My Swedish step-grandmother, who crossed the Atlantic on an airplane to marry Arthur four years after my grandmother died, served the pancakes on white china bordered in blue flowers. She swirled lingonberries into whipped cream and heaped it all into a glass bowl like an ice cream sundae.

1

“I am not afraid.” A few weeks later and back in Minneapolis, I read these words written by a man I admire in response to the bridge falling. He’s a pastor and a father and I know he was doing what parents do. They say to their trembling children, “Here take my hand. I’m not afraid.” Then the children lose their fear; their parent’s courage displaces it.

But I can’t write that same compact declaration, and I read in his words a challenge to do so. I can list the reasons why I’m not afraid that bridges—or towers—fall, citing risk statistics and articles of faith. Even so, the human tremble rises up at the prospect of bad news. I’m old enough to know that a parent’s love, faith, and fear are often in a crazy internal knot even as he or she firmly grips that younger hand.

2

The way my mother’s wrist swirled through the invisible parabola as she gripped the frying pan and spiraled the batter into a circle across the pan’s surface made all the difference in what ended up on our plates. Her standards for symmetry, laciness, and delicacy elevated the perfect swirl to the level of artistry.

The swirl yields its prize, however, only in combination with the perfect frying pan. The pan must be heavy enough to withstand and conduct the heat evenly, but not so heavy the wrist can’t easily hold and move it. Before I got married, my mother made sure I had the right pan, just as her mother had done for her. We stood in the department store’s cookware section while she picked up each candidate, testing its feel in her hand and its maneuverability as she did the swirl.

I take out this pan now and turn on the gas flame under my stove’s lower right burner. I’ve learned over the years that pointing the burner’s control knob to the one o’clock position ensures a flame not too high, not too low.

1

A Newsweek web exclusive suggests that the bridge fell due to pigeon dung, an acidic excrement known to corrode nearly any metal. Other headline stories blame a flawed design, cracks and corrosion, substandard concrete, years of strain from trucks bearing weight beyond the legal limit, and ignored inspection warnings.

Engineers are trying to recreate the bridge from its wreckage along the river’s edge, south of its original site. The first bolt to break or supporting beam to buckle may never be determined, but it’s easy to speculate that a general carelessness among the stewards of public safety was an early domino to fall.

2

The pan heats over the flame. I pass my fingers under running water and then hold them over the pan and watch the action of the water droplets when they drip onto the pan’s surface. These sizzle and evaporate; the pan needs more heat. A minute later I try the water trick again, and this time the drops do their dance, skipping and leaping on the pan’s surface.

For the first pancake, I place a small sliver of Crisco in the pan, about the size of the fingernail on my little finger. It melts nearly instantly, and I use a metal spatula to spread it over the pan’s surface. For subsequent pancakes, the sliver will be about half that size. Butter would smoke and burn in a pan this hot.

I transfer a spoonful of batter to the pan’s center with my right hand, and with my left, I lift the pan off the burner. I swirl my wrist as my mother did, and the thin batter rushes to its rightful size and shape. After about eight seconds, I slide the spatula underneath, and flip. The first one always lacks the lace pattern and browns unevenly, but it primes the pan for those that follow.

As each pancake comes out of the pan, I stack them on a plate covered with a pan lid to keep in the heat. A stack of about fifteen signals that its time to call my husband and sons. They inhale deeply and smile at the dual aroma of coffee and pancakes.

1

Thirteen people died in the bridge collapse and about one hundred were injured. One of the men who died drowned while helping others get out of their cars. Another man died when his semi hit the side of the bridge. The truck’s movement to this position perhaps stopped the school bus full of children from going off the sheared edge. The current theory is he careened his truck into the bridge side, at the cost of his life, for that very purpose. All the children lived.

One woman who survived said that when her car stopped falling, people were everywhere helping those in cars and in the water get out and to safety. She called them her angels. A friend of my older son—tall, broad shouldered, always smiling and laughing, infused with a joy kindred to Arthur—was near the bridge when it fell and bolted down the riverbank to help pull people out.

2

“Come and sit down,” I say. “Start eating.” The pancakes are never eaten in solitude as a bowl of corn flakes or toast and jam often are. Neither are they carried on a plate from room to room, pushed into the hungry mouth by the forkful while getting dressed or gathering papers for the day ahead. My husband and sons each take a seat. I stand behind mine.

Now God be thanked. Reality shifts and Beauty, already present, welcomes Peace and Life and Joy to the feast; we bow our heads to their transcendent First Cause. We lean into the stream of mercy that sings over rocks, rolls and rushes across continents and bodies of water and generations.

The stack of pancakes circles the table. I run back the ten steps to flip another pancake. I keep cooking while they eat, walking back and forth between flips to join the conversation. I sit down intermittently and toward the end.

We talk about school, work, friends, music, and books. The spoken word swirls around the table’s center of gravity. The tender pancakes carry the gentle sweetness of maple syrup, the sharp sweetness of lingonberries. We wipe our mouths and laugh.

My husband gets up to make another pot of coffee. I check that there is still cream in the pitcher.

“Are you full yet?” I ask. “Who wants more?” The extravagance of this meal stuns me. There is always at least one more egg to crack, one more galup-galup of milk to pour from the carton, a couple more spoonfuls of flour, another sliver of shortening. The common ingredients transformed by heat and swirls and served amid bursts of color lavishly feed our hunger.

1

I went to look at the bridge site one month after it fell. The Tenth Avenue Bridge had reopened for traffic after being closed for several weeks. Chain-link fencing rose up from its west side and one lane had been closed off for pedestrians. The walkway was as crowded as any at the state fair.

Six stories below, the twisted metal looked as insubstantial as an erector set, as flimsy as a bobby pin. The rust caked like refried bean residue on silverware. The concrete surface lay peeled off like a sheet of vinyl flooring. The exit sign I had followed countless times stood propped on its side in debris at the river’s edge.

People clamored for a spot at the fence. Cameras clicked. We grow up singing the nursery rhyme and playing its game—“London Bridge is falling down, falling down, falling down”—but what do we really know of such things?

2

The pancake stack disappears. The last of the coffee sits in the mugs. A few drips of syrup and lingonberries glisten on the wood’s surface. We are happy about each other and we are full. My mother told me Arthur’s last words before he died were, “Gud är så god.” (God is so good.)

I know not to waste suffering or fear. I know to use them as hard lessons, to extract the nugget of what I have yet to learn or what I need to learn yet again or what I can only hope to someday learn. But how not to waste these moments?

We’ll soon get up from the table and do who knows what and drive who knows where for all the rest of our lives. But here, now, the wholeness of this moment, dense and round as a concrete piling driven deep into bedrock, anchors our paths. This is what it feels like when all is well. A mnemonic of experience as real as any. Might not a person just tip right over from the weight of fear or angst without this ballast at the other end?

[1] This essay was first published by The Other Journal as “Things that Fall and Things that Stand” in Leslie Leyland Fields, ed., The Spirit of Food: 34 Writers on Feasting and Fasting Toward God (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2010), 98–110. Reprinted here with permission from Wipf and Stock Publishers.