While most people idly converse about evil in the broad terms required for superheroes and populist understandings of international relations, terms that envision evil as locked in a battle against good, few attend to the implications of viewing good and evil in Manichaean terms. Beyond assuming that the good is so simple as to have one static definition, such talk also requires that evil have an intentionality and essence that ultimately would require that it negate even the good of its own being. Western philosophical and theological traditions avoid making recourse to an “evil” entity by defining evil as privation—the loss or absence of what is good. In the Platonic sense, the origin of evil is ignorance, a lack of knowledge, for—as Socrates ably demonstrates to Thrasymachus—the goods of wisdom and justice cannot conflict. In the Christian tradition, evil is caused by the privation of God: it is only in the context of godlessness that we do wrong. In modern philosophy, Immanuel Kant speaks of evil as originating in our inability to be consistent, our failure to love the good for its own sake: even those people with the best intentions supplement their desire for an absolute good with a relative good that eventually corrupts the system. Understanding the evils that we do and suffer from in terms of the absence of well-being requires our accepting privation as an explanatory model.

This understanding of evil as privation also suggests that evil functions as a temporary movement between different goods. All senses of suffering and loss depend on a good that precedes the loss, and the work of redemption—the healing of body and soul—enables a restoration of the good after a loss. This is one way of understanding Job, whose experiences of personal evil as loss are presented between two tales of a life of plentitude and wholeness: for all of the ambiguities of this text, it would seem that one message, at least, is that suffering—even when extreme—is finite. Privation relates evil with good in a dialectic manner: we understand evils in relation to goods, and we can celebrate our goods only after we have already experienced privation and loss. The benefits to privation are many: we appreciate the primacy of the good and remain hopeful that, like Job, we will eventually experience redemption. Just as scars suture together a wound, wholeness and closure seem destined to eventually take the place of pain and emptiness.

However, although the privative model generates a discussion of popular culture and politics, and more profoundly allows us to make meaning out of our loss and suffering, it is inadequate as a foundation for revealing or responding to evil. This inadequacy can be viewed in two ways. First, an evil that occurs through violation or the marring of conceptual goods is difficult to articulate in a privative framework—words fail to grasp the nature of what has been lost—and victims are thereby deprived of being able to articulate their loss as a wrong. Second, some evils—especially systemic evils—are impersonal in nature. We resign ourselves to these evils because they exist at such a large scale that they can infiltrate our world silently, unseen by those trained to look for the blatant, simple evils portrayed in movie theaters or the nightly news. Although the model of privation is functional, we need a new model of evil that will allow us to articulate, discuss, and challenge more subtle wrongs.

The work of this paper is to provide a model of evil that permits us to speak about, and thus confront, more insidious forms of evil. I begin by defining dis-integration as a systematic form of wrongdoing whose hurt uniquely disables healing: unlike disintegration, which allows for a later period of re-integration, I claim that dis-integration is a dissembling whose rupture denies wholeness. I test this model by revealing how dis-integration is able to identify and discuss evils that infect natural, basic, social, and reflective kinds of goods through addition—not subtraction. I then conclude by showing how dis-integration is able to function as a heuristic: I examine the systematic abuse, neglect, and mistreatment of Native American women—evil acts that the United States government and most citizens are willing to overlook, especially because understandings of evil based on privation are unable to reveal the type of evil we perpetuate. In defining evil as dis-integration, I hope to empower us to confront this type of evil and to thereby remove artificial obstacles that prohibit healing.

Defining Dis-Integration

The term disintegration is relatively new: the earliest use cited in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) occurs in a 1796 book on minerals that describes the process by which exposure to air and moisture causes a mineral to fall to pieces. Although one would not define erosion as an “evil” per se, erosion nonetheless seems amenable to traditional conceptions of evil in that it incorporates a sense of privation and loss—here, the loss of integrity. The importance of this initial definition, however, is its mention of a supplement that occurs prior to privation. In other words, the material disintegrates when it encounters air and moisture: its privation comes in relation to its system being supplemented with external factors. My thesis is that this notion of an external supplement can be carried into evil: dis-integration, as a model for evil, is one that is better equipped to look at evils that are supplemental in the way that they cause privation.

The OED defines disintegration as a natural process, one driven by entropy to break things down into their simplest parts. We understand this symbolically in our personal experience when our world and lives become broken and those goods that we see as crucial to our identity—our jobs, our family, our friends—are wrested away from us by forces outside of our control. The term evil is then applied to the feeling of loss and deprivation, to the un-wholeness we experience. At this metaphorical level, disintegration’s opposite, integration, can itself be seen as a good. We see this throughout the Western tradition, from Plato’s conception of Justice as the harmonious balance of the parts and the whole (which is an image of integrity) to the notion of creation in Genesis, where every part of the system is instrumental to an increasing sense of the good. Integration is also implied in the good of redemption, as seen in the parables of Jesus where the kingdom of God is found when everything lost (coins, sheep, sons) becomes re-integrated into a whole. This echoes the physical sense of re-integration we observe when natural systems are able to re-integrate material that is lost in one place into another part of the ecosystem: the igneous rock that erodes upriver will likely turn into a sedimentary stone over time.

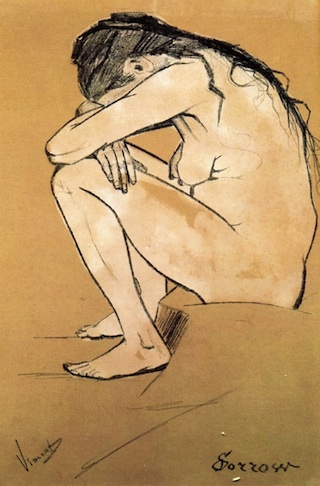

Disintegration is also implicated at a mythological level: the philosopher Paul Ricoeur writes that, at a primal level, evil is understood in terms of a stain or defilement. This is the most embodied of Ricoeur’s symbols of evil, which we experience viscerally through the bloodstains that accompany murder and sexuality. The primitivity of stain is expressed by Ricoeur’s description:

In truth, defilement was never literally a stain; impurity was never literally filthiness, dirtiness. It is also true that impurity never attains the abstract level of unworthiness; otherwise, the magic of contact and contagion would have disappeared. The representation of defilement dwells in the half-light of a quasi-physical infection that points toward a quasi-moral unworthiness. This ambiguity is not expressed conceptually but is experienced intentionally in the very quality of the half-physical, half-ethical fear that clings to the representation of the impure.1

The power of the stain is thus the way that it embodies the sense of fallenness and the loss of purity, the lingering mark of the privation from a former state of innocence or good. Ricoeur argues that stains give rise to language, shaping our vocabulary of the pure and the impure.

Dis-integration can also be used as a way of explaining how a stain educates our conception of evil. At a physical level, a stain is something additional or superfluous that we see added onto an object in a way that cannot be integrated. If I spill coffee on my shirt, the stain is something that is on but not of the shirt, something that prevents the shirt from being seen as a thing: more than a shirt, it is a stained shirt. My ability to see the stain dis-integrates what once had been its own whole. At a deeper level, Ricoeur validates the notion of dis-integration by connecting the idea of a stain with the logic of exclusion. He writes that “the ‘interdiction’ which excludes the accused from all sacred spaces and public places . . . signifies exclusion of the defiled from a sacred space.”2 The stain thus forms a supplement that dis-integrates the accused from society, and Ricoeur writes that the exile or death of the accused is necessary to annul the defilement in a double negation. To be clear, the punishment of exile dis-integrates the accused from social, economic, and basic goods, sundering the individual into an enforced isolation—death also dis-integrates the accused from these goods, but it re-integrates the accused at a material level back into nature. Unlike many assumptions of evil, then, the model of dis-integration reveals how sustained dis-integration from a variety of goods is a fate worse than death, as death grants re-integration at least at one level.

The natural, metaphorical, and mythic registers inform but do not specify the model of evil I propose, which is why I use the term dis-integration to speak about systematic evils done to humans. I posit that dis-integration occurs when a person or entity supplements a system in such a way as to prevent another person from integrating with the system while simultaneously preventing the affected person from leaving. This encompasses a twofold privation: on the one hand, the person targeted by dis-integration is isolated or excluded from its initial context and, on the other hand, this person is not allowed to re-integrate elsewhere. To be dis-integrated is to be intentionally excluded from the systems that had constituted home. This evil is not necessarily only one-dimensional; instead, one can be dis-integrated from goods found in multiple systems—natural, social, spiritual, psychological, economic—through an initial supplementation. To clarify, I am not arguing that disintegration is an evil—in fact, the disintegration of certain social classes and customs in the name of equality has been a good thing. Importantly, dis-integration differs from disintegration in that it attempts to suspend the status of a particularized element, slowing down the dynamics of change which otherwise constitute the system.

Testing Dis-integration

David Klemm and William Schweiker helpfully explore the initial goods presupposed by calling dis-integration “evil” in their book Religion and the Human Future. The key value they primarily hold up is the “integrity of life,” which manifests in the domains of natural, basic, social, and reflective goods. Biologically, the value of the integrity of life calls for the integration of distinct levels of goods—basic goods of survival, social goods of community and recognition, and reflective goods of art and thinking—into some livable form. Ethically, it demands a life dedicated to respecting and enhancing the proper integration of these goods and a commitment to the well-being of other forms of life. It manifests spiritually as a wholeness and steadfastness toward the proper aim of human existence.3

Natural Goods

Although natural catastrophes are spectacular, the death and damage they cause are not inherently dis-integrating. As the law of the conservation of matter posits, nothing can come from nothing: matter can neither be created nor destroyed. Natural death—through drought, flood, fire, earthquake, or tsunami—tends to be self-regulating as the material that had been alive is re-integrated into the natural system. Thus, privation in a natural system can be understood as the loss of the good of life, but this is a loss that swiftly provides the matter for new life to emerge. Life and death remain integrated.

What does upset the system of nature is a class of compounds known as POPs, or persistent organic pollutants, chemicals noted for their ability to linger in the environment for long periods of time and with toxic consequences. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention notes that even though the use and emission of POPs was stopped in the middle to late 1970s, we are still exposed to them at low levels, generally in our food. One particularly unpleasant type of POP is PCB, or polychlorinated biphenyls. According to Soren Jensen, the Swedish chemist responsible for identifying PCB compounds, PCB “constitutes perhaps the most stable group of organic substances in existence. It poses, therefore, a severe threat to life-forms.” This stability indefinitely delays re-integration into nature, as it remains extremely stable “against both chemical and biological attack,” which means that the burning of oil or wastes simply expels PCBs into the atmosphere. Although “the acute toxicity of PCB is not very high,” Jensen found that it can cause damage to skin and to the liver.4 When mixed with food, as it was in Japan, it led to death and high rates of miscarriage. Other types of non-integrateable waste products produced by humans include polystyrenes (such as Styrofoam) and nuclear wastes, the latter requiring from tens of thousands to millions of years to become re-integrated into the environment. The concept of dis-integration usefully articulates how these types of pollutants can be classified as evil and draws attention to the way that they affect biosystems as a whole by including supplements that preclude re-integration.

Basic Goods

For Klemm and Schweiker, basic goods “are those goods which inhere in finite life independent of human choice, but which are necessary to sustain human agency.”5 Evil would prevent access to these basic goods that human life requires: on a biological level, cancer seems to conform to the structure of dis-integration. On the one hand, cancer cells are mutated varieties of cells that the body is unable to use: these cells either are voided as waste, or are stored as tumors or amyloid deposits. Either way, cancer cells are unlike most other cells within the body because the body cannot break them down and re-integrate them into a bodily economy. In time, especially if these cells spread, the individual is dis-integrated as his or her body begins to fail, no longer allowing the enjoyment of the goods of eating, drinking, sleeping, or breathing. The model of dis-integration is able to name cancer as an evil, not only as it causes the loss of loved ones (thus articulating an evil that privation also names) but also because, at the embodied level, these cancers cause the body to dis-integrate and, in its dis-integration, deny basic goods on an objective level. Cancer cells, which deprive us of the basic good of health by dis-integrating the body, can thus be identified as evil in themselves.

Social Goods

Klemm and Schweiker provide a usefully broad definition of social goods, defining them as inclusive of “family, economic and political institutions (of whatever form), friendship, patterns of interaction with other species, and even the means to think, speak, and act together with others.” One moral evil that dis-integrates an individual’s ability to enjoy social goods is sexual abuse, particularly rape. Privative definitions of evil clearly describe this as wrong, and the model of dis-integration accounts for the variety of systems wronged by these assaults, which dis-integrate the physical wholeness of the victim, introduce into the psychological system a memory that is difficult to integrate, and perpetuate the dis-integration of the individual from the social world. Steven Peterson and Bettina Franzese argue that a sexual assault causes fear, isolation, self-blame, and reclusiveness; put simply, they claim that “sexual abuse and fear leads females to turn away from the outside world—including the political realm.”6 The combination of these effects becomes self-generating: fear leads to increased isolation, and time spent in isolation increases mistrust of the outside world. In other words, defining evil in terms of dis-integration highlights the problem that violated individuals are dis-integrated from a world that, in reflecting reminders of their former normalcy, only serves to delay the possibility of re-integration.

A second example, torture, has been justified by politicians as occasionally necessary during times of crisis. Using the vocabulary established above, torture can be seen as introducing a violent supplement to the target’s body with the goal of dis-integrating the target’s sense of self from the body, and this act has the long-range effect of dis-integrating the individual from social goods. In the first part of “Psychology of Torture,” the writer Sam Vaknin argues that “the torture victim’s own body is rendered his worst enemy. It is corporeal agony that compels the sufferer to mutate, his identity to fragment, his ideals and principles to crumble. The body becomes an accomplice of the tormentor.”7 Citing the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) manual on torture, Vaknin adds that torture is intended to “to disrupt the continuity of ‘surroundings, habits, appearance, relations with others’” because a “sense of cohesive self-identity depends crucially on the familiar and the continuous. By attacking both one’s biological body and one’s ‘social body,’ the victim’s psyche is strained to the point of dissociation.” Vaknin argues that the intention of torture is to reprogram “the victim to succumb to an alternative exegesis of the world, proffered by the abuser” which means that

torture has no cut-off date. The sounds, the voices, the smells, the sensations reverberate long after the episode has ended—both in nightmares and in waking moments. The victim’s ability to trust other people—that is, to assume that their motives are at least rational, if not necessarily benign—has been irrevocably undermined. Social institutions are perceived as precariously poised on the verge of an ominous, Kafkaesque mutation. Nothing is either safe, or credible anymore.

Thus, supplementing the victim’s body with intentional physical and psychological pain at an embodied level can be seen as effecting the dis-integration of the person from both basic goods (the relationship with the body) and from social goods (an ability to trust others or interact in the social world).8

Reflective Goods

Reflective goods, according to Klemm and Schweiker, “satisfy not only the drive for meaning in human life, but also open the possibility for creating new forms and ways of life . . . they are the goods of culture or civilization, that is, the entire domain of symbolic, linguistic, and practical meaning-systems.”9 To dis-integrate a reflective good thus requires more than simply eliminating the physical goods that result in reflective goods, as happens in book burnings or in vandalism of artworks. Overall, these actions at most could eliminate a particular instance of meaning or a particular good, or even a set of goods—they would leave a human’s capacity to benefit from reflective goods untouched. To identify how evil dis-integrates reflective goods can most easily be seen in larger cultural systems. Evil dis-integrates when an entity supplements reflective goods ideologically and thereby dis-integrates a target audience from being included in the possibility of meaning. This leads to the creation of reflective goods that reinforce the meaninglessness of the lives of a target audience; binding this target audience to the history of oppression and perverting the possibility open to others in the meaning system.

One example of the dis-integration of reflective goods is the treatment of African Americans since the eighteenth century. Toby Jenkins, in his article “Mr. Nigger: The Challenges of Educating Black Males within American Society,” argues that a wide range of social pressures make it difficult for Black men in America to participate in or access reflective goods. Historically, Jenkins argues that this is rooted in the fact that until 1867 it was illegal for Blacks of any age to be taught to read, despite the fact that higher education in America has a three-hundred-year history. The fact that literacy for Blacks has only moved from 44 percent in 1900 to 57 percent in 2000 shows that something is working to block Black access to reflective goods.10 At a material level, the absence of literacy eliminates the possibility of accessing a wide variety of reflective goods, including visual media (television and movies) and music.

Eliminating the possibility of literacy kept some Blacks in the eighteenth century from the meaning system made available by reflective goods (although this effort was thwarted in the continued production of music and the fact that some Blacks were educated despite social convention). The second aspect of the dis-integration of the Black community in America from reflective goods occurred 130 years later. Jenkins writes “that as laws forced society to discontinue direct forms of racial prejudice, television became the new medium to disseminate stereotypical perspectives. And it proved even more successful than the first, as it reached an even greater audience and attacked Blacks even in the privacy of their own homes.” The pervasive nature of the media means that “African American community identity has largely been established in relation to the definitions given to it by the larger society,” including “how to speak, what to believe, how to look, and how to define success.” This results in a social stereotype of Black as “villain and outcast” that Black men are forced to either embrace or fight against but relative to which all are forced to live. By systematically reinforcing the absence of the possibility of contributing to or profiting by reflective goods and by using reflective goods (especially music, movies, and videos) as a medium to reinforce the absence of possibility, Black men can be seen as dis-integrated from the reflective domain through the systematic elimination of access to those reflective goods that would encourage re-integration. In this way, the model of dis-integration is able to account for that which a privative account would identify as evil (the experience of poverty and low levels of literacy), but it also shifts the focus to how these individuals are dis-integrated in a systematic way. The privative account encourages our empathy, as we mourn the loss as something that has happened in the past, whereas the model of dis-integration reveals the structure through which this loss is made possible and it thereby encourages us to make changes in the present that will allow for a future re-integration.

Dis-Integration as Heuristic: Defining the Scope of Evil

In addition to allowing us to speak of evil as it occurs at any one level, an understanding of evil as dis-integrating also reveals how evils imprison people at multiple levels of dis-integration. Victims affected by dis-integration on multiple levels are reduced to a state similar to what Giorgio Agamben calls “bare life,”11 which refers to humans who are able to be killed without being sacrificed. While Agamben’s focus is on how people die, the sorrow of the dis-integrated is being denied even the closure (and re-integration) permitted by a death. Individuals who are dis-integrated at multiple levels are the least advantaged in any given society, and therefore are the most in need of assistance.

One of the most horrifying examples of evil identifiable as dis-integration in our world involves the abuse of Native American women. Overall, Native Americans experience almost twice as much violent crime as the average American, and an estimated one-third of Native Americans have experienced physical abuse. The 39 percent of women who report being victims of domestic violence is likely an underrepresentation, and Native American women are particular targets—they report experiences of violent crimes 50 percent more frequently than Black males. That 75 percent of these crimes are caused by non-Native American perpetrators is problematic because tribes are unable to prosecute non-Native Americans. Although the federal government is supposed to provide protection, Public Law 280, affecting 52 percent of tribes in the continental United States, complicates this arrangement by shifting legal authority from both tribe and federal governments to state and local officials, and because this is an unfunded mandate, it leads to an enforcement gap. Even crimes that receive legal attention rarely result in the protection of women; indeed, a 2004 Department of Justice study found that tribes lack necessary programs or facilities to aid survivors.12 A lack of federal, state, local, and tribal resources—and widespread resignation and apathy—means that Native American women continue to disproportionately suffer.

These women can be said to suffer from a privation of love and law, a pitiable state; however, understanding them as dis-integrated does more to reveal the pervasive nature of their plight. The initial sense of “native” bespeaks an opposition that began as a colonial project, and these kinds of colonial projects can be classified as evil as they supplement an existing economy (native groups using the land for hunting and farming) with an additional force that dis-integrates the original harmony. This was done in America as European groups perpetuated their value structures of racial and cultural superiority using military power, and this assumption of superiority can be seen as an evil committed against native groups on multiple levels.

The initial systematic evil done to indigenous tribes in colonial societies was the dis-integration of individuals from their land. This was done through pre-emption, as the government argued that it alone was able to buy and sell land from tribes. In addition to creating a monopoly, the government in this way also inserted itself as a supplement to an economic system of exchange. The ultimate consequence of this supplement was the interpretation that Indians did not own their land—they merely occupied it—which was then used to justify the dis-integration of tribes from their traditional lands as occurred in the Trail of Tears.13 Problematically, Indians were not considered citizens and thus were given little legal ground from which to argue their claims. Thus, the first consequences of the supplement of the Anglo-European government—which quickly became our federal government—into North America was the dis-integration of Indians from natural and legal systems.14 This ultimately led to the Removal Act of 1830, when tribes were forced to be physically dis-integrated from their lands, and extensions of this act led to further reductions of Indian lands, from 138 million acres in 1887 to 48 million acres in 1934. Almost half of the remaining land is either arid or semi-arid, which shows the perpetuation of evil relative to the basic goods of food and employment.

The supplement of federal authority over the sovereign authority of indigenous tribes also led to the dis-integration of social goods through the destabilization of tribal organization. One example of this occurred on the Colville Indian Reservation, where multiple tribes were thrust into the same geographic vicinity and then were instructed on how to determine which individuals were and were not part of the tribe. Federal officials told tribes how to constitute tribal relations, leading to a result Alexandra Harmon describes in the following way:

Had council decisions been final, Colville enrollees would have been an enigmatic mix of people possessing all possible degrees of aboriginal ancestry, hailing from all corners of the Northwest, and sharing only an ability to persuade most councilmen that they identified with Indians already on the reservation. Of course, council votes were not final. The commissioner refused to enroll anyone who lacked aboriginal ancestry or appeared on another reservation roll, for example.15

The demands of the federal government thus dis-integrated social goods in three ways: they forced different groups onto the same land; they mediated what it meant to belong to the tribe—and they didn’t necessarily take all of the native recommendations—and they forcibly removed Native American children from their social environment, placing them in boarding schools and programs “designed to eradicate traditional culture, family patterns, and communal behaviors.”16 This clearly shows how systems of tribal relations, supplemented by federal interventions, dis-integrate definitions of family and politics by inserting elements that fundamentally and irrevocably alter the original social structures.

Finally, the assumption of cultural superiority and the mediating influence of federal governance led to the dis-integration of reflective goods as European languages and traditions supplanted native ones, leading to a loss of indigenous art, language, and religion to the point that the Choctaw Tribe was scheduled for termination in 1969,17 consistent with what Robert Miller calls the Termination era. With the advent of activism and the Red Power movement, the US policy relative to Indians has since changed to one of self-determination; however, this has not successfully led to re-integration—most telling, perhaps, in the situation of Native American women. The sum total of these dis-integrations create situations in which Native American women are able to be violated with impunity as bare life and without recourse to goods that most Americans take for granted.

Examining dis-integration in the context of Native Americans clarifies how evil functions at a systemic level: by supplementing a system in a way that isolates one element, we do evil by restricting the ability to integrate while also eliminating the possibility of leaving the situation, and this also results in a privation of goods. The benefit of using dis-integration as a model is that one can use it to analyze patterns within systems and that it does not rely on the ability to identify any one agent as “responsible” for the evils that are generally long standing and diffuse. By refusing to become mired in questions of blame, we hopefully can also begin to work toward the re-integration of those who are systemically denied goods.

Removing Supplements

To conclude, I will offer a final example of the benefit of using dis-integration as a model of evil against the more traditional model of privation. Although Haiti has long been known for its poverty and political instability, little had been done to assist the country beyond occasional military interventions. The most recent of these, Operation Uphold Democracy (1994–1995), successfully restored President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power. The change in power alleviated some abuses but did nothing to help Haiti’s reputation as being impoverished and burdened with entrenched criminal activity. The Bush administration, which did not favor Aristide, sidestepped the government and gave funding to nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). As Jeneen Interlandi of Newsweek reported,

“Our government started giving all of its aid directly to NGOs,” says Paul Farmer, U.N. deputy special envoy to Haiti. “And our policies influenced those of other countries and international financial groups.” As the most capable workers flocked toward the new, comparatively high-paying NGO jobs, the Haitian public sector waned; health and education went from bad to worse, and already rampant corruption grew and spread. (November 8, 2010)

The inherently unstable situation caused by a country that depends on and uses foreign aid for its basic needs was made worse as the monies were directed and distributed in unsystematic ways. Rather than looking for ways to help the country achieve a better sense of political and financial integration—for the good of the people living there—politics took an unstable situation and made it worse.

In January of 2010, a massive earthquake struck Haiti, destroying its infrastructure and displacing thousands of people. Using a model of evil as privation, fund-raisers advertised the need for food, clean water, and materials for shelters that would help to restore the country. These fundraising efforts were initially successful: in the ten days following the earthquake, donations were made at the average rate of $1.64 million per hour.18 In six months, over one billion dollars in donations had been given, enough to cover the basic necessities of food and water needed to sustain life. Donations slowed by July of 2010, when the trauma of the oil spill in the Gulf shifted the public’s attention. According to the November 8, 2010, edition of Newsweek, despite

$8.75 billion for reconstruction and the coming of a veritable Haitian renaissance, progress has fizzled on practically all fronts. Yes, shelters have been set up—tents and tarpaulins, mostly—but they offer scant protection against hurricanes like Tomas, which bombarded towns around Port-au-Prince late last week.

Using a privative model of evil encouraged a type of short-term thinking that made people believe they were fixing the problems of Haiti. The more complex situation—including the fact that most citizens were systematically deprived of basic, natural, and reflective goods before the earthquake due to the supplement of nongovernmental organizations and criminal activities—was ignored.

After two years and $2.38 billion dollars of pledged aid, Haiti is still in conditions that must seem all too familiar. On January 12, 2012, Sara Miller Llana of the Christian Science Monitor reported that while “approximately 1 million people have been relocated, some 520,000 still live under tents and tarps at 758 camps across the capital,” with “an additional 200,000 Haitians who are in equally vulnerable situations, having moved into overcrowded conditions with families or other nonsustainable arrangements.” Llana goes on to add that many Haitians are still being deprived of basic and natural goods, including food.

Although the natural disaster that overwhelmed Haiti would have been devastating even in the best of circumstances, earlier attention to the evils caused by Haiti’s dis-integration could have resulted in a country better able to deal with disaster. For instance, the relief efforts in Japan, an island nation devastated by a natural disaster fourteen months after Haiti, are much farther along. Instead of continuing to worry about displaced populations, the focus in Japan is on the possibility that it will recover its economic position by the end of 2012. Rather than diminish the pain and tragedy suffered by those in Haiti or Japan, my point instead is to highlight the horrifying consequences of dis-integration. The abstract evils that linger in Haiti may not lead to record-breaking levels of donations, but it is crucial to speak about dis-integration in order to address the systemic evils that continue to destroy the integrity of life both here and around the world.

1. Ricoeur, Symbolism of Evil. (New York, NY: Beacon Press, 1986), 37.

2. Ibid. 39.

3. Klemm and Schweiker, Religion and the Human Future (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008), 76–78.

4. R. Y. Wang, R. B. Jain, A. F. Wolkin, and L. L. Needham, “Serum Concentrations of Selected Persistent Organic Pollutants in a Sample of Pregnant Females and Changes in Their Concentrations during Gestation,” Environmental Health Perspectives 117, no. 8 (2009): 1244–49; CDC quoted in Wang et al., “Serum Concentrations,” 1244; and Jensen, “The PCB Story,” Ambio 1, no. 4 (1972): 123 and 127.

5. Klemm and Schweiker, Religion and the Human Future, 76.

6. Ibid., 77, and Peterson and Franzese, “Sexual Politics: Effects of Abuse on Psychological and Sociopolitical Attitudes,” International Society of Political Psychology 9, no. 2 (1988): 282.

7. This and all subsequent Vaknin quotations in this paragraph are from “Psychology of Torture I,” Knol, July 30, 2008, http://knol.google.com/k/psychology-of-torture#.

8. See Henry Shue, “Torture,” Philosophy and Public Affairs 7, no. 2 (1978): 124–43. Here, Shue argues that killing people is less morally wrong than torturing them in times of war.

9. Klemm and Schweiker, Religion and the Human Future, 78.

10. Jenkins, “Mr. Nigger: The Challenges of Educating Black Males within American Society,” Journal of Black Studies 37, no. 1 (2006): 132 and 144. Note that my capitalized usage of the term Black in this paper follows that usage of Jenkins.

11. Agamben, Homo Sacer (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998), 8.

12. R. A. Hart and M. A. Lowther, “Honoring Sovereignty: Aiding Tribal Efforts to Protect Native American Women from Domestic Violence,” California Law Review 96, no. 1 (2008): 188, 190, 205, 208, and 212.

13. Robert Miller, Native America, Discovered and Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis & Clark, and Manifest Destiny (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 175.

14. Ibid., 166.

15. All information about Colville is from Harmon, “Tribal Enrollment Councils: Lessons on Law and Indian Identity,” Western Historical Quarterly 32, no. 2 (2001): 175–200.

16. R. Bubar and P. J. Thurman, “Violence Against Native Women,” Social Justice 31, no. 4 (2004): 73.

17. V. Lambert, Choctaw Nation: A Story of American Indian Resurgence (Lincoln, NE: U. Nebraska Press, 2009), 61–110.

18. Timothy C. Morgan, “US donations to Haiti average $1.64 million per hour,” Christianity Today, January 22, 2010, http://blog.christianitytoday.com/ctliveblog/archives/2010/01/us_donations_to.html.