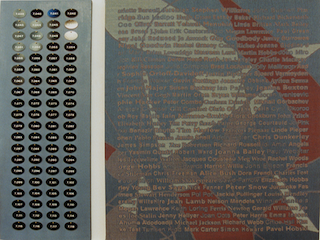

Paul Hobbs, By Name, 1995, woven cloth and discs, 106 x 98 cm, artist’s collection. Courtesy of the artist.

On the left I have placed a gray board covered with black plastic discs, each engraved with a sequential number. They remind me of cloakroom discs, soldiers’ dog tags, perhaps prison numbers. The discs are identical except for a change of digit. The first is 7,039, the last 7,118, to suggest we are some way into a sequence. The numbers do not start at a round figure, nor do they end in a round figure. And if any of the discs were removed or replaced, one would barely notice. They are all eminently disposable.

We are immersed in these kinds of numbers. We have numbers for our bank accounts, tax IDs, insurance plans, passports, zip codes, cell phones. These numbers say a little about us, yet none of these numbers fully defines us. Our names, however, link us with our family, our community, and even our nation. They suggest something of our character and affirm our humanity. In naming someone we show them respect and dignity.

On the right is a brightly coloured woven cloth covered in names. There are about 150 names listed here, set in four typefaces. The names include politicians, sports figures, artists, murdering despots, and actors. Two-thirds of the names are ordinary people who are not in the news. But all of the names belong to real people. And just as the numbers in the left column appear mid-sequence, the visible names are run off the edge—so one reads “phie Hacker” instead of ‘Sophie Hacker,” or “iegfried Sassoon” not “Siegfried Sassoon”—as if more names could be found to the left and right, as if, perhaps, we all may appear on this list. The names are not ordered alphabetically or grouped according to kind. They stand as individuals, all of equal worth. Most importantly, they are all woven into the cloth. To remove any name, one would have to cut it out, forever ruining the whole.

[nggallery id=9]

In Matthew, Jesus told of a farmer who planted wheat in his fields. At night the farmer’s enemy sowed weeds there and later the man’s servants asked, “Where did the weeds come from? Shall we pull them up?” “No,” replied the farmer, “for you might uproot the wheat with them. Wait till harvest. Then collect the weeds and burn them, and gather the wheat to the store” (see Matt. 13:24–30). One day there will be a final reckoning, suggests Jesus, but in the meantime evil people will be allowed to live among the good. And every person has the chance to turn from evil, repent, and claim the forgiveness of Christ, so long as they are alive.

As I crafted this piece, I was challenged by this parable and by the life story of Comrade Duch (Kang Kek Iew), the former director of the Khmer Rouge prison Tuol Sleng who was jailed for life in March 2012 for organizing the torture and murder of more than 12,000 men women and children. In the years after the fall of the Khmer Rouge, he worked as a teacher, met a Cambodian American missionary, and became a Christian. Later he was tracked down by a journalist and exposed in an article. He then gave himself up, and he is the only member of the former Khmer Rouge regime to have confessed to his crimes.

In the parable of the Lost Son, Jesus spoke of the son who returned from his dissolute life, expecting to beg for his father’s mercy and a menial job. But his father ran out to meet him, reinstated him, and celebrated with a party (Luke 15:11–32). It’s easy to imagine the local drug dealer as the son in this story, to see him turning to Christ, walking up that path and finding God the Father, who knows us each by name, running out to meet him, embracing him and bringing him home. But can we imagine Comrade Duch receiving that kind of welcome? That is the kind of question I hope to inspire with this work—can we imagine a truly repentant former torturer or a former mass murderer gaining that kind of forgiveness?