In this two-part interview, the theologian J. Kameron Carter discusses his current work regarding political theology and the construction of the modern racialized world, speaks about the Obama presidency and the recent Occupy movement, and reflects on theology’s ongoing work in the wake of colonialism. In part II of the interview, Carter addresses the Obama presidency and the so-called post-racial moment, considers the shooting of Trayvon Martin, and frames theological education in the wake of modernity as a “criminal act.” Catch up on the conversation by reading part one.

The Other Journal (TOJ): Let’s talk about your work in light of the present moment in American politics. For example, the 2008 presidential campaign of Barack Obama represents a significant shift in the landscape of American politics in terms of how identity has been taken up as a political issue. During his campaign, despite much talk about America’s supposedly post-racial moment, Obama’s American identity was most sharply interrogated during the controversy over his relationship with Rev. Jeremiah Wright, culminating in his speech on race, “A More Perfect Union.” Since his election, he has faced a controversy over the validity of his citizenship, he has been accused of being a Muslim, and he has been accused of being a socialist, among other things. All of these accusations are attacks on his identity that throw his status as an “authentic” American in question. How might this shed light on the continuing question of race and identity in America, specifically in terms of how you have articulated citizen subjectivity?

J. Kameron Carter (JKC): Let’s back up to the 2008 campaign. Many of the things that Obama has been continually accused of in his presidency already announced themselves in the 2008 campaign. The question of his race and religiosity was put front and center in the Jeremiah Wright controversy, particularly because Wright was taken as a kind of synecdoche and symbol for black Christian theology, which, in the way it was talked about in the press, was deemed an abhorrent form of Christianity, precisely because of its radicalism. In that context, Obama had to put some distance between himself and Wright, and in response, he gave one of his most important speeches. It’s packed full of interesting, illuminating, problematic things that are worth a great deal of reflection.

Then, in the midst of that debate, there is the rise of Sarah Palin. God forbid if I stay too long on Sarah Palin, but there are a number of ways to understand Palin, and I think one way we must meditate on her cultural significance is that she became a kind of response to everything that Obama was being accused of lacking. If Obama was suspect as to his birth, she was not. If Obama was suspect as to his Christianity, she was the kind of quintessential representation of the evangelical Christian, and so on and so forth. I think that one of the reasons that John McCain really was pressed to bring Palin onto the ticket as his vice presidential candidate was because she was the symbolic response to Obama.

What you have here is a contest of Christianities. The presidency itself became a staging ground: the campaign for the presidency, for the political space of the presidency and what the president symbolically represents for the nation, became a “sight,” or a to way to see, and a “site,” as in a way to locate our great anxiety over the meaning of Christianity in the present conjuncture. Simply because Obama was elected doesn’t mean these issues have been put to rest. The proof is the Tea Party movement, which is a kind of refraction of what Palin represents. And so, ever since Obama has been in the presidency, he and his presidency have continually been on trial.

Here I can’t help but reference the killing of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin of Sanford, Florida. There have been national protests and a great deal of international attention on this incident, with cries minimally for George Zimmerman’s arrest as a start toward justice for Martin and social justice in the land.1 But beyond this there are deeper, extralegal factors because much of modern law presupposes them. To explain what I mean, consider President Obama’s one guarded comment in response to the killing. Obama was guarded in his response for at least two reasons. One, race has been a spectral presence in his presidency, and every time that specter has made an appearance, there’s been trouble. There was the Wright incident in the campaign, the Shirley Sherrod incident, and the famous “beer summit” in the wake of Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s unwarranted arrest in his Boston home. Each of these incidents spelled trouble for the Obama presidency. He was damned if he dealt with them and damned if he didn’t. The second reason he was guarded was that this is still an open case and there still is an ongoing investigation.

Without doubt, Obama knew he would be questioned about the incident and he was ready with what he wanted to say. At a press conference shortly after the issue went national, Obama said that his heart went out to the parents of Martin over what had happened to their son, and then he said something most telling. He said that if he had had a son, his son would look like Trayvon Martin. This is a powerful statement. While calling for the law to work with deliberate speed, he shifted from the register of law to the register of representation; his comment suggested that this incident is a moment within a wider event and crisis.

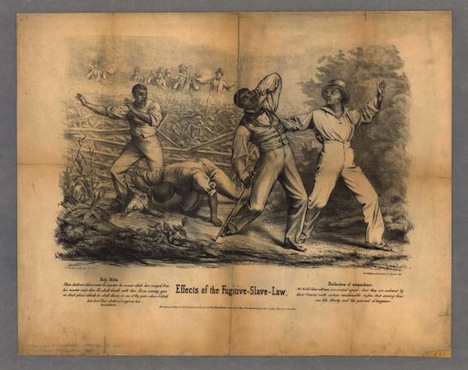

I call it the crisis of the gaze or what one scholar has called a problem of “the right to look.” That is, in our society, who has the right to look and at what and whom?2 Furthermore, that gaze is one of violence. This gaze, which I call iconicity, visualizes some people as the normal, as the proper citizen, and others as improper citizens (at best) or noncitizens or criminal (at worst). Martin was caught within this icon-onomy—and the law itself participates in this icon-onomy; the law is not anterior or posterior to the icon-onomy or the logic of looking. The hoodie, as an item of clothing, was the flashpoint. The hoodie communicated to the one with the right to look (and thus the supposed right to judge) that what was being looked at was a criminal, not just in his activity but in his being (his very existence was criminal). But why just a hoodie? There are many folks who wear hoodies, including white folks. I suggest that the hoodie was a kind of prosthetic, an extension of Martin’s blackness. That is to say, it’s the equation hoodie + blackness = criminal being that we saw enacted in the Trayvon Martin incident. And thus, the hoodie became on Martin’s body a signifier of blackness and thus of criminal being. When Obama said that if he had a son that son would look like Martin, I believe it is this problem he was gesturing toward. And so, among the many kinds of problems that are associated with this killing, legal among them, it’s also a problem of the icon and the gaze.

Patristic thinkers like John of Damascus, Theodore the Studite, and Patriarch Nicephorus of Constantinople taught that icons train us how to see, how to look at the world. My claim is that blackness in modernity functions as an icon. It has been mobilized to train us—to train the Zimmermans of the world, indeed, all of us—how to look at the world. I suggest that that look is both in and already inside of an economy of social violence, which authorizes itself with the force of something like divine authority. In the modern situation, the situation that we are all trapped inside of, race— blackness—will find you if you’re black, just like it found and tracked down Martin. That’s the point. Obama knows that. If Obama didn’t know it when he got into the presidency, he surely knows it now. My work has been to reckon with the fact that this problem I’ve been describing has been mediated by a certain vision of Christian faith, a vision of faith that I take to be a profound distortion of Christianity. Therefore, a big part of my work is to analyze this problem and by working through it, to imagine what it would look like to think of Christianity beyond itself, to think of Christianity after Christianity.

For more of our interview with J. Kameron Carter, please subscribe to our print edition!

1. Zimmerman was arrested and charged with second-degree murder on April 11, 2012.

2. See Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).