Lately I’ve been reading God in Pain: Inversions of Apocalypse (Seven Stories Press, 2012), not so much a dialogue but an series of interlinear monologues between Continental philosophy’s enfant terrible Slavoy Žižek and Croatian radical orthodox theologian Boris Gunjević .

The title is slightly misleading, if only because without knowing what is actually in the book, one has the immediate – albeit false – impression that one is about to read some avant-garde version of process theology, The Divine Relativity 2.0 or something pushing the envelope even further? Fifty Shades of Gray for the discreet postmodern philosophical fantasizer?

In reality – and thus far more interestingly – it is a sophisticated effort to take the previously published exchanges between Žižek and Milbank contained in the academic “best-seller” The Monstrosity of Christ and radical orthodoxy founder John Milbank on to significantly different terrain. After reading through it I have to say, paraphrasing Dorothy on her arrival in Oz, “Toto, we’re not in Pomoland any more.”

The horizons have shifted. So where then are we? That’s a very good question. Whether we like it or not, it seems we’ve arrived – finally – at the “end times”. And the end times means we’ve left behind postmodernism as we know it.

The End of the Postmodern?

Žižek has been telling us for quite a while now – in his own inimitable Žižekian fashion – that the “end” is already, not will be (It’s what scholars for several generations have dubbed “realized eschatology”. Find , for example, the proper point in history.). That seems to be the major theme, at least, of Žižek’s writings and pronouncements since he published in 2010 a provocative mishmash of essays focusing on the folly, inanity, and depravity of Western “progressive” culture entitled Living in the End Times. But here he really gets down to business regarding what it means for Christianity as a whole.

My purpose here, nevertheless, is not to review Inversions of Apocalypse. Largely because of its topical electicism and weird lack of symmetry with Gunjević’s slightly eccentric paens to radical orthodoxy from an Eastern European perspective, the book seems almost unreviewable. But the book does give you a certain shock of recognition, the realization – long in coming – that we are not where we were theologically and paradigmatically even half a decade ago.

If, as I myself wrote thirty years ago “deconstruction is the death of God put into writing,” then whatever God in Pain represents is the death of deconstruction put into writing. The era of deconstruction in the West (approximately 1978-2004, the year of Derrida’s death) coincided with the golden age of Western consumer capitalism. The collapse of consumer capitalism over the last half decade perhaps has been an “event” that , like the death of God in Nietzsche’s parable of the madman, “has still not reached the ears of men.”

Just as many scholars today debate over what Nietzsche truly foreglimpsed in terms of civilizational markers when he uttered this famous prophecy that seemed to come overwhelmingly true in the wars and nihilistic violence of the the twentieth century, so we still have not yet grasped, or sorted out, what is yet “on its way” today, even though unlike the death of God we can probably date it, i.e., the fall of 2008.

But can we not genuinely ask like Nietzsche, though in an entirely different way presently, “are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? ” Žižek and Gunjević make it clear that is where we seem to be from their perspective. Their ruminations are what they call “inversions of apocalypse”, because they place all familiar eschatological premises on a purely immanent plane.

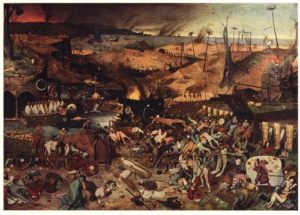

Although as two Eastern European intellectuals who have still not gotten over the fall of Communism they continually make gratuitous and hopeful allusions to “the revolution”, their arguments – even Žižek’s – are thoroughly what I would term “pietistic” at their core. If pietism historically was radical religious subjectivity in the face of overwhelming human disaster (e.g., the Black Death) or political persecution (e.g., a refusal to bow to the brutal imposition by a central monarch of religious conformity), Žižek’s and Gunjević’s new millennial inverted apocalyptical pietism amounts to a kind of highly disciplined authenticity in the face of an uncontrollable unravelling globally of all connections, meanings, banal certitudes, socio-economic institutions and linkages, and forms of association (etc.) – yes, Virginia, even the “friendship” of all your Facebook friends!

Immanent Apopcalyptic Piety

Žižek’s type of discipline is largely personal and of course psychotherapeutic. He wants you to be brutally honest with yourself about your desires, even your darkest ones, and to rid yourself of any lingering idealistic or theo-spiritualistic hypocrisy about who you really are. It is all about creating a present apocalyptic subjectivity, one that actually mimicks God in his decision to become man.

Žižek, by way of explanation, thinks there was nothing “inevitable”, providential, or – God forbid – logical (as Anselm assumed) in the incarnation. It was actually a desperate gamble that actually worked, a cosmological Hail Mary pass that was miraculously caught in the end zone. Christian subjectivity, therefore, consists in a kind of Lacanian realization of the impossibility of desire itself and of subjectification as pure truth-telling , positing one’s “I-ness” not as a new identity but as one “dispossessed of all substantial content, as the self-regulating negativity of an empty singularity.”

It was the same with God, according to Žižek, when he sub specie aeternitatis let go of his own self-engendered Big Otherness , when he as “universal Substance” had to “‘humiliate’ himself, to fall into his own creation,” and “to appear as a singular, miserable human individual, in all its abjection, abandoned by God.” (169)

The themes of abjection and the painfulness of singular subjectivity in a desolated environment coincide naturally with the ever more popular literary genre we dub “posthuman” or “postapocalyptic.” One has only to consider such runaway bestsellers as Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, or Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games. One wonders whether the haunting

scenario of The Road, where a dying and unnamed father in an utterly devastated, post-apocalyptic landscape turns over the task of “carrying the fire” in a seemingly hopeless world, does not closely mime Žižek’s vision of both the divine and human condition.

Gunjević’s vision, however, is not existentialist and absurdist, but what he terms “ecclesial.” His template is Saint Augustine’s meditations on the collapse of Rome and and the historical, if not the eschatological, hope that springs from the ongoing corporate “spiritual exercise” of a renewed holy, catholic community – perhaps even while the barbarians are storming the gates of the urbs mundi. “Pray and work,” as the monks did throughout those dark and archiveless centuries we read about in the textbooks on Western civilization. That seems to be Gunjević’s formula.

Augustine’s coy tension between the unmanifest “city of God” and the crumbling “city of man” plays itself out in much the same way the “ecclesial” functions in contemporary radical orthodoxy, which Gunjević’s breathtakingly sees as the true ideological redoubt from which to withstand the barbarian onslaught.

One gets the feeling that authenticity in the face of apocalypse, for Gunjević, is not unlike living out some highly sophisticated fantasy of nineteenth century Gothic Romanticism. British academics singing matins and expatiating on the the relevance of Scotus to sociology, while the guys in bearskins ransack the administration building at Oxford, strikes me more, however, as the gag for a Capital One commercial than a serious proposal for perservering through the dark times.

Living in the End Times

If postmodernism has become an unconscious, high-brow parody of our legacy, which a lot of pomo types have effectively trashed anyway, “how then should we live”? – if I myself am allowed to indulge in a little parody of Francis Schaeffer. Should we now live with the apocalyptic mindfulness – no matter how “out there” particular accounts of what it entails might appear to us – that both Žižek and Gunjević remind us is what Christianity eminently comes down to in the end. No matter how we configure it, postmodernism has always been a kind of pre-eschatology, not so much a praeparatio evangelium but a praeparatio apocalypsis.

Derrida’s now forgotten essay around 1980 on the emerging “apocalyptic” tone in contemporary philosophy offered a hint of this tendency. Deconstruction was never, as many believed, simply a game of “gotcha” with establishment types, technocrats, or traditionalists. There may have been nothing outside the text, but inside it one could always hear a distant and increasingly loud rumbling.

If “revolution is not a picnic,” as Mao Tse -Tung was supposed to have said. Similarly, apocalypse is not a graduate philosophy colloquium, as Jesus didn’t say, but of course strongly suggested. All you need to do, of course, is read Matthew 24.

Popular culture tends to focus on total, planetwide disasters brought about by some collectively preventable form of social irresponsibility (environmental degradation, arms accumulation, the unleashing of biotoxins, etc.). But the Biblical genre, from which all the latter day variants ultimately derive, focus almost exclusively on God’s dealing with his chosen ones, whoever they might be.

In the “little apocalypse” of Matthew Jesus warns specifically about getting all riled up about both natural and general human disasters (e.g., “wars and rumors of war”). These may be “signs” of the times, but not of the eschaton, Jesus stresses. God’s judgment comes down to a separation of various species of sheep from goats, of deceiving apperances from the real deal, of those who claim to have the answer from those who maintain a kind of non-pretentious innocence about what is actually going to happen, which to be sure only God knows.

All things considered, it’s not simply about living resolutely and authentically – that is to mistake Christianity for Heideggerianity. It’s about God vindicating those who don’t fit into the global or religious norms of the day at all, those whose only virtue was not so much how they lived, but their “faithfulness” to the end.

Call it a unique type of cosmological exceptionalism, if you wish.

Watching Out for Thieves

The takeaway from all Biblical, or even pseudopigraphal, apocalypses is that the eschaton “arrives” both at times and in ways we rarely expect – like a “thief in the night”. And the New Testament is clear – that apocalyptic figure and General Patton commanding the cosmic D-Day invasion of divine power is looking for one thing, and one thing only, when he arrives – faith.

It is not, as far as Jesus was concerned, about righting global wrongs or rewarding those who all along had the proper answer to the question “how then should we live?” The Pharisees had the proper answer, but we know the rest of the story.

Jesus in the Gospel of Luke tells the parable of the “unjust judge” who finally dispensed justice to the woman who had enough faith to harass him day and night. “And will not God bring about justice for his chosen ones, who cry out to him day and night? Will he keep putting them off? I tell you, he will see that they get justice, and quickly. However, when the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on the earth?” (Luke 18:7-8).

So what does this mean for us when so much academic and popular discourse seems to be striking unprecedented apocalyptic tones?

If I have to choose between Žižek and Gunjević, I will opt for the former, only because it is not his suggestions on how to live, but his own “a/theological” (in more than one sense) parable of why God decided to become human that matters.

For Žižek, it was act of faith – not faith in God but God taking a “leap of faith” on his absolute own in an almost pure, transcendental, Kierkegaardian sense. Why did he take such a “risk”? It was “for us.”

If we are to be “ecclesial” in the era of apocalypse, it has little to do with clerical organization and adopting the latest, new and improved version of academic ecclesio-theology, even if it still carries the pomo label. It is about being Christs in the most Christ-like way to each other, as Luther once said.

That is what we truly mean by apokalypsis.

Carl Raschke is Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Denver. His latest book Postmodernism and the Revolution in Religious Theory: Toward a Semiotics of the Event (University of Virginia Press) is scheduled for publication this fall.