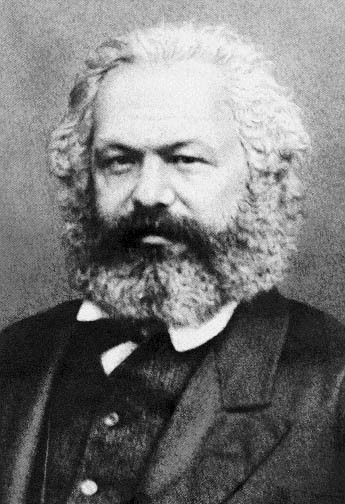

Karl Marx in Christian Theology—Promising or Perilous?

Karl Marx is as well known for his atheistic and materialist critique of religion—Christianity especially—as he is for his theory of capitalism and revolutionary praxis. Indeed, he famously argued that “the ‘criticism of religion’ is the conditional premise of all criticism,” the purpose of which is to uncover the material reality of the human condition under “the illusionary sun” of theological “niceties.”1

Marx is not a sort of crypto-theologian, nor is there a religious remainder in Marxism itself, and yet I do think that Marx’s critique of religion can help Christian theologies be more Christian and so aid Christian churches in becoming more like the biblical ekklesia. I am not merely suggesting that Marx’s critique of religion discloses inconvenient truths about the contemporary forms and practices of the Christian church and, in so doing, aids and abets the church’s rediscovery of itself, even if, in the end, it dispenses with Marxian thought. On the contrary, my claim is that Marx ought to be read by the church as an apocryphal prophet who might help us become more Christian.2

Christians have long associated Marx with the dark sociopolitical history of communism and the reductive vulgarities of atheist materialism, and Marx’s critique of religion seems to be congruent with the Enlightenment’s rejection of classical Christian theological beliefs and the legitimacy of religious authority in public life. It is true: Marx was not friendly toward religion or theology, and he was averse to Christianity specifically, which he considered historically complicit in the alienating and reifying effects of capitalism on the working and producing classes. He resisted the idea that “the social principles of Christianity” should be counted on to support and promote social liberation or economic justice:

The social principles of Christianity preach the necessity of a ruling and oppressed class, and for the latter all they have to offer is the pious wish that the former may be charitable. . . . The social principles of Christianity are sneaking and hypocritical and the proletariat is revolutionary. So much for the social principles of Christianity!3

But if we stop here, we will overlook some important aspects of Marx’s critique of religion, aspects that can be of great help to the church as we recalibrate our notions of faithful Christian life to our current social and political conditions. What is problematic for Marx about religion and theology is its alienating and ideological character, an issue that Christians still face today. We have much to learn from Marx about how to identify and combat it in our midst.

To be clear, I am not simply suggesting that in Marx, the Christian church (especially in the United States) finds reasons to disentangle our theo-logic from our longstanding affiliation with the economic and social goals of capitalism. Nor am I arguing that returning to Marx represents an opportunity for a liberal, religious socialism akin to the now defunct Social Gospel of the early twentieth century. To make either of these points would simply be an echo of other interesting work done elsewhere, most notably by self-proclaimed Christian “radical” Shane Claiborne, New York Times journalist Ross Douthat, and philosopher Ken Surin.4 Instead, what I want to say here is that Marx can teach us something about the nature of religion and theology, and so he can help us revitalize our own understanding of what Christianity is and what it means to be a Christian in today’s world.

Marx’s Critique of Religion: A Brief Overview

For the sake of clarity, I will condense Marx’s critique of religion to four points: (1) religion as the “opium of the people,” (2) religion as ideological “false consciousness,” (3) religion as commodity fetishism, and finally, (4) religion as money. I think that each of these four critiques of religion double as theological sites for Marx, and so within them lie important lessons for Christian theology and for Christian churches about the politics of discipleship, or in Marx’s parlance, the social-practical activity of revolutionary praxis.

To take Marx’s view of religion seriously as an immanent critique does not necessitate that we all become materialists, atheists, or (even worse for some of us) socialists, but I do think that in attending seriously to Marx’s critique of religion, we can still find catalysts for the church to become better at being Christian: a globalized and diverse faith community that works in advocacy, action, and resistance, suffering with and for others for the sake of a more just, equal, and gracious world, a world where all lives are livable, all bodies are recognized, and all deaths are equally mourned.5 This may sound a lot like Marx’s utopian political dream, but it is also the Christian hope of heaven, as displayed in both the prophetic tradition of the Hebrew bible (i.e., Amos, Isaiah, Hosea) and in the moral vision of Jesus Christ’s kerygma (e.g., “proclamation”) in the New Testament. Certainly, later Marxist readers, such as Theodor Adorno, Ernst Bloch, and Paul Ricoeur, have found ways to think critically about utopia, not as a purely eschatological expectation of that which lies in the future but as the benchmark for what one should hope for in the redemption of the past and strive for in the present. In modern Christian eschatology, this critical dimension of utopia is present in voices as diverse as Enrique Dussel, Jürgen Moltmann, and Marcella Althaus-Reid, all representatives of a Marxian critical legacy in their own way.6

Religion as the Opium of the People

So, how does Marx describe religion, and why—and in what forms—does he consider it problematic? Marx’s analysis in “Toward a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right” is one of the most well-known texts in modern philosophy:

The struggle against religion is therefore indirectly the struggle against that world whose spiritual aroma is religion. Religious suffering is the expression of real suffering and at the same time the protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, as it is the spirit of spiritless conditions. It is the opium of the people.7

The central metaphor used by Marx here speaks to the ambiguity at the heart of his critical analysis of religion. As the “opium of the people,” religion is both the “expression” and “protest” of a certain social situation. It attests to and arises from a complex set of material realities that conditions economic exchange which, in turn, produces “real suffering.” Emphasizing the social dimension within which religion is always producing and being produced, Marx interprets religion as both the testimony of the experience of oppression and the consequence of various contradictions at the core of the productive forces and social relations that are operative in the economic base of human experience. This aspect of Marx’s understanding of religion is highlighted in his use of the infamous opium metaphor, for in Marx’s day, the use of opium was conterminous with both the protest and suffering of the working class under capitalist conditions. As one commentator recently noted,

In the nineteenth century, opium expressed the immiserization of the people. Opium use increased with declining conditions for the working class: more health problems, and the outbreaks of epidemics such as cholera. As [Friedrich] Engels, for example, pointed out in The Condition of the English Working Classes (1845), declining health was directly related to the ravages of capitalist relations. Opium thus “expressed” in an indirect way the ravages of capitalism on the health and well being of the population, but most particularly the workers.8

An avowed atheist and historical materialist, Marx followed his friend Ludwig Feuerbach in denying the existence of God as anything other than an “illusion,” a “projection” of human desires, aspirations, and values into an abstracted, idealist transcendence that only rips humans from the soil of their lives: the real social relations and productive forces that are the stuff which make human life human. Feuerbach’s goal, the goal of all true criticism as Marx saw it, was to invert this way of thinking, to turn thought and action away from “heaven” and return it to the messy register of “earth,” “law,” and “politics” where real life processes occur. Marx thought that by setting critical thought back on its political feet, perhaps we might get to the real work that needs to be done. Marx writes in his eleventh thesis on Feuerbach that “the philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.”9 To do this, Marx found it necessary, at least in the early stages of his work, to critique religion. He believed that the kind of consciousness that religion offers only prevents social actors from recognizing the world as it is. In this way, religion was problematic not because it was “false” but because it was ideological. In other words, speaking in terms of the history of class struggle, religion works in the favor of the ruling class—it hides and covers up the reality of social life, naturalizing what is constructed and universalizing what is particular. This makes it appear to the working and producing class as if the social relations and productive forces of their material lives are factual givens when they are actually a direct effect of the alienation and reification of human life under capitalist relations, an effect that benefits the bourgeois at great expense to the very workers and producers who are paying the price with their labor.

So we see that Marx’s critique of religion has as much to do with his moral and political critique of oppression (something that Christian churches certainly should be able to support!) as it does with any sort of anti-theological argument about such religious beliefs as divine transcendence, life after death, et cetera. It has more to do with the effect of religion on social and political life and the role that religion has in perpetuating oppressive, heartless, and spiritless conditions. I believe that Marx has something important to say to Christianity about the effect we are having on the world at large, and if we are wise, we will listen.

Religion as Ideological False Consciousness

To further understand Marx’s critique of religion—and to assess what it ought to mean for Christians and for churches today—it must be situated within his much broader analysis of ideology as “false consciousness.” This task is difficult because Marx’s treatment of religion and ideology is fragmented, unsystematic, and ambiguous. But Marx’s concern with ideology, and the place of religion in ideology, has again to do with Marx’s political interest in the economic contradictions of social relations and productive forces, the real effects of which wreak havoc on the most vulnerable persons in modern life. To Marx, ideas become ideological when they are used to or function to protect and benefit the interests of the dominant classes through manipulation, deceit, and pretense. Instead of seeing the truth, workers take on ruling ideologies in their social consciousness, which causes them to think and act differently than if they knew the actual truth about the economic contradictions that determine their material conditions.

What is this truth that ideology hides, according to Marx? The workers and producers are at the mercy of the capitalists who use them as instruments in their ongoing quest to manufacture, market, and sell commodities. This system of exchange and production actively alienates workers from the products of their actual work, from themselves, and finally from each other. Ideologies act in various strategic forms, all of which have deleterious effects on the human actors. These forms are, in many ways, the very things that comprise human life under capitalism: money, products, commodities, and labor. Through these forms, ideologies hide contradictions in economic reality, reify social relations, and alienate humans from themselves, each other, and the products of their work. These forms embed themselves in the economic fabric of history and society in such a way that only the ruling class benefits: “the ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force.”10 Marx’s point is that religion is a superstructural element of human life that is constituted by economic conditions and so it can often function as an ideology in the hands of the ruling class. For Marx, an ideology leads to a social form of human consciousness that passes its appearance (independent of history and society) off as reality (material conditions). In this way, religion can become an instrument of oppression that further reifies persons, turning relations (to self, others, and the products of their work) into so-called things which, in turn, confront their creators as alien, hostile, and threatening.

Religion as Commodity Fetishism

In his later analysis of capitalism, Marx turns to the process of commodity fetishism. Commodification is that fetishizing activity that transforms social relations into things that can then get exchanged and transacted in the market. In fetishization, social relationships are objectified; they are reified as something vulgarly economic, which covers up their intrinsic value, replacing it not in terms of use (what meets human needs directly) but rather in terms of exchange value, or what the commodity is worth in relation to other commodities. Marx explains the problems with commodities in an early section of Capital: “We have seen that when commodities are in the relation of exchange, their exchange-value manifests itself as something totally independent of their use-value.”11 The crude relation of market exchange becomes the dominant mode of relationality in capitalism, not only between commodities but between persons as well. This ideologically masks or covers up the true economic character of social relations and productive forces, especially played out between the working producer and the capitalist manager.

For Marx, a fetish is a specific mode of commodity, “abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.”12 Roland Boer recently suggested that our notion that Marx thinks of fetishism as a religious idea is supported by its frequent mention in his unpublished notebooks and his study of world religions, complete with many biblical quotations and theological allusions.13 The (religious) problem with fetishization is comparable to the problem of alienation and reification of labor and capital; it switches the qualities of human social relations with that of objects, conferring upon them a transcendent, enchanted value, a mystification that finds its ultimate site in that of capital itself. Commodity fetishes oppose and antagonize their producers as external to them and their creative powers. These fetishes reverse the natural mode of object production, where there exists a natural, positive relational connection between the producers and the objects they create for their own use, to meet her own needs. But the ultimate crime of the fetish is that it is not a primarily mental operation but one that reproduces itself innumerable times within social reality itself, specifically in religious forms:

As against this, the commodity-form, and the value-relation of the products of labor within which it appears, have absolutely no connection with the physical nature of the commodity and the material relations arising out of this. It is nothing but the definite social relation between men themselves which assumes here, for them, the fantastic form of a relation between things. In order, therefore, to find an analogy we must take flight into the misty realm of religion. There the products of the human brain appear as autonomous figures endowed with a life of their own, which enter into relations both with each other and with the human race. So it is in the world of commodities with the products of men’s hands. I call this the fetishism, which attaches itself to the products of labor as soon as they are produced as commodities, and is therefore inseparable from the production of commodities.14

Marx shows us how religion often is performed as a fetishistic exercise. Religion and its practitioners, who economically benefit from its endurance, enchant it with a sort of transcendent and abstracted magic so as to increase its own marketability and its viability as a commodity: its value in relations of commodity exchange, or as we would say today, its brand. To apply this to today’s religious scene, where religion is broken down into partitioned components and reified for consumption, to fetishize religion into a commodity only increases the disparity between its use value and its exchange value as it is traded back and forth in transactions of sale and purchase. As an example, one could cite the popularity of religious kitsch, religious theme parks, the men’s and women’s conference speaker circuit, and the use of religious advisors in corporate America. Certainly an in-depth materialist analysis of the world market for these items and services would be required to fully explain why they emerge and how they become so popular. Nevertheless, this only benefits those in power and influence who control the religious market and the factory of religious goods, such as religious services, theological beliefs, liturgical rituals, sacramental practices, vestries, youth social groups, and Sunday school meetings. These acts, even though they are likely to benefit those at the top, distress the social relations “on the (churchly) ground” so much as to alienate those who are most religiously active and instrumentalize those who are most in need of its redemptive message and moral vision.

Religion as Money

Marx is perhaps at his most theological in his critical analysis of the capitalist fabrication of money and its dominating effects on society as the primary mediating activity. Marx interprets money as the medium of capitalist exchange, an activity which is explained through a theological analogy that illustrates how it produces alienation in social life. The very essence of money is to function in a mediating role that actively dehumanizes persons as workers by externalizing that which is properly their own and setting it against them, self-alienating them, and making them Others to their selves. Their own will, the product of their labor, and those to whom they are constitutively related confront and threaten them in the mediating activity of the money relation.

Marx turns to theology for an analogy through which to explain the alienating nature of representation and what happens to it in the case of money. He argues that in theology, Christ “represents originally,” and thus is seen as the “ideal mediator.” The unique identity of Jesus Christ as “two natures united in one person” means that Christ represents humans before God, represents God before humans, and finally represents humans to other humans.15 These relations mirror the way that money represents private property for private property, society for private property, and private property for society.16 In other words, ideologies detach humans from the context and product of their work by supplanting the natural and direct “as such” relation with a historical and indirect “as if” representation. Money, like Christ, steps in and acts like an indirect mediator between producers, products, and consumers, separating and dividing natural relations with constructed ones. But Marx goes on to suggest, in the fashion we have already described in detail, that Christ, like money, alienates persons from their proper value. God only has value insofar as he represents Christ, and the persons only have value to the extent that they represent Christ. Money operates the same way. Money plays in capitalist society as a mediator of religious value; it is fetishized and then it reifies social relations and productive forces into a rigid, given thing whose inflated and enchanted exchange value determines our own value, which is always already mediated between objects and ourselves.

Can Christians Preach Marx in Church?

So my main question remains an open one: Can we take Marx to church with us or does his atheistic and materialist critique of religion render him irrelevant or, worse, perilous for guiding Christian theology and church life? Marx’s critique of religion is not motivated by a vulgar materialism nor does he replace religion with worship of the secular basis of social relations. Instead, Marx’s critique of religion has interesting resonances with the message of biblical prophets like Amos, Hosea, and Isaiah, whose condemnation and indictment of Israel’s unfaithfulness challenges its complicity, hypocrisy, and reticence in regard to the concrete realities of social and political conditions of the time. For them, as for Marx, what is needed is for the faithful to return to the practical activities of “faith in history and society” and embrace “the cost of discipleship,”17 even at the risk of losing cultural prestige, political power, and economic cachet. Amid the crushing, oppressive effects of advanced capitalism on the global scale—detachment between producers and consumers; wage exploitation of poor, local communities by wealthy, global corporations for the sake of profit; the inability of workers to purchase the very products of their creative labor creates; and profound ecological devastation, to name a few examples—this is a lesson that we desperately need to hear anew in the church.

My point is that Marx is not as interested in abolishing religion per se as he is in exposing and critiquing its materialist base. He is interested in surpassing the abstractions of theological idealism and refocusing the attention of true criticism on the oppressive and dominating dynamics of the social world. He wants to identify the theological causes of reification and alienation as they affect the real, active processes of human life. Marx is imminently critical of religion where he finds it because of the way it continues to do harm at the most basic levels of human life—and this is a critique we should all share! In this way, I consider Marx better at being critical of Christianity than we are; he sees in religion, and in Christianity specifically, a propensity to sponsor and promote material conditions that dominate persons rather than emancipate them.

I do not believe that Marx’s fight is directly with religion. Rather, his critique of religion is a means of making a revolutionary critique of the social world, specifically of the capitalist way that the materialist conditions which make up the “earth” work only for a precious few and alienates a great many others. He wants to return our attention to the struggles and suffering that happen in this world, to keep our theological heads out of the heavenly clouds, and to open our economic eyes to the destruction taking place before us. Indeed, if we in the church are to find any common cause with Marx, we can certainly find much on this score. The church has had a front row seat to the social and political ills of capitalism and does have to look long or far before it finds intratheological reasons to resist this way of being and acting. It has watched as capitalism’s unholy gospel of self-interest, competition, and consumption has turned against us, dominating and exploiting us, rendering us hollow, empty and longing for something altogether different.

Much of what our contemporary churches do today is driven by the goal of being successful in the world market; our churches are often motivated more by corporate organization theories on messaging, branding, and advertising than by the theological particulars of the biblical moral vision. Marx calls for us to enact a thoroughly immanent critique of idolatry and fetishism within the church, asking us whether or not we have caved to the materialistic and consumerist desires of our culture in return for the cultural power of our institutions, economic security for our leaders, and market desirability for our brand(s).

Our pastors and church leaders are usually more concerned about targeted growth than they are about economic justice, social hope, or the everyday struggles of local politics in their communities. Churches are not nearly as engaged in advocating for fair wages, labor safety, or corporate oversight as they should be; they do not see their kingdom work as having something to do with this earth, unless it has something to do with abortions, guns, or sexuality. Marx gives us the critical tools to ask why this is and to discover the inconvenient truth under the ideologies that masquerade as our so-called gospel.

This is not to say that Marx strips away unnecessary theological accouterments that conceal some lost core or pure essence. Instead, preaching Marx in church affords us the terrifying but promising opportunity to be confronted by critical theory, a form of interrogation whose practical purpose is always human emancipation or “to liberate human beings from the circumstances that enslave them.”18 This does not spell an end to the church, but rather presents us with an opportunity to renew our commitment to the sociopolitical dynamics of becoming Christian—even if that calls for a radical evaluation of the current form and voice of our faith communities.

On top of this, Marx challenges all religious traditions, especially Christians, to consider and question their relationship to capitalist economies. This requires us, in some cases, to acknowledge those instances when either our complicity or complacency has resulted, intentionally or not, in an unholy cooperation with capitalism. We must come to understand the extent to which Christianity has been put up for sale in our cultural milieu, enchanted with fetishistic qualities, and taken on the mediating function akin to that of money. Indeed, Marx is something of a prophet when it comes to the way that religion, especially Western Christianity, is now expressed and treated as a commodity fetish in our contemporary culture. Theodor Adorno said it this way:

Religion is on sale as it were. It is cheaply marketed in order to provide one more so-called irrational stimulus among many others by which the members of a calculating society are calculatingly made to forget the calculation under which they suffer.19

Marx got it right when he argued that Christianity fits particularly well with the story that capitalism tells about the inherent nature of humans and the way we naturally interact with our environment.20 But this story is one that is a decisively modern story; it is also strange and distant to the politics of Jesus Christ and it is alien and contradictory to the biblical mission of the church to the world. Why Christianity has found it so important to attach itself to the goals of capitalist society is not hard to decipher, but the matter of why it continues to do so, considering the destructive effects on our global world, is an increasingly disturbing question. By advocating that religion interrogate its materialist base, Marx joins his voice with the Hebrew prophets in articulating a way out for Christianity that helps Christians be less capitalist and more human, and as such, more Christian.

1. Marx also says that “The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions.” For both passages, see Marx, “Toward a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: Introduction,” in Karl Marx: Selected Writings, by Karl Marx and Lawrence Hugh Simon (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, [1844] 1994), 28.

2. The extent to which such a reading is equivalent to becoming more Marxian is a more complicated question that I will not take up here.

3. Marx, “The Social Principles of Christianity,” in Marx on Religion, ed. John Raines (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, [1847] 2002), 185–86.

4. See Shane Claiborne and Chris Haw, Jesus for President: Politics for Ordinary Radicals (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008); Claiborne, The Irresistible Revolution: Living as an Ordinary Radical (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2006); Douthat, Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics (New York: NY: Free Press, 2012); Douthat, “Can Liberal Christianity Be Saved?,” New York Times, July 14, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/15/opinion/sunday/douthat-can-liberal-christianity-be-saved.html?_r=0; and Surin, Freedom Not yet: Liberation and the Next World Order (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009).

5. This description of the meaning of contemporary politics is paraphrased from the work of Judith Butler. See Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. (London, UK: Verso, 2003).

6. See Dussel, Beyond Philosophy: Ethics, History, Marxism, and Liberation Theology (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003); Moltmann, Theology of Hope: On the Ground and the Implications of a Christian Eschatology (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1967), 20ff and 230ff; and Althaus-Reid, The Queer God (New York, NY: Routledge, 2003).

7. Marx, “Toward a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,” 28.

8. Andrew M. McKinnon, “Reading ‘Opium of the People’: Expression, Protest and the Dialectics of Religion,” Critical Sociology 31, no. 1/2 (2005): 25.

9. Marx and Engels, “Theses on Feuerbach,” in The German Ideology: Including Theses on Feuerbach and Introduction to the Critique of Political Economy (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1998), 571.

10. Ibid., 67.

11. Marx, “Capital, Vol. 1, in Karl Marx: Selected Writings, 220.

12. Ibid., 280.

13. See Boer, “Opium, Idols and Revolution: Marx and Engels on Religion,” Religion Compass 5, no. 11 (2011): 698–707; and Boer, “That Hideous Pagan Idol: Marx, Fetishism and Graven Images,” Critique 38, no. 1 (2010): 93–116.

14. Ibid., Capital, Vol. 1, 233. Italics added for emphasis.

15. Marx, “Excerpt: Notes of 1844,” in Selected Writings, 42.

16. Ibid.

17. Here I cite two famous books, one from the Catholic political theologian J. B. Metz and the other from the Protestant political theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Metz, Faith in History and Society: Toward a Practical Fundamental Theology (New York, NY: Crossroad, 2007); and Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1969).

18. Max Horkheimer, Critical Theory (New York, NY: Seabury, 1982), 244.

19. Adorno, Notes to Literature, vol. 2., trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1992), 294.

20. For more theological specifics on this historical relationship, see the very fine Mark C. Taylor, After God (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2007).