For a while, I hoped to frame this essay in terms of a dramatic interchange—something along the lines of “A Slovenian philosopher, a British theologian, and a Swiss dogmatician walk into a bar . . . ”1 Alongside an eye-wateringly hip assemblage of cinematic references, literary allusions, and comedic scenes—my early favorites being when Barth imagines a young adult novel entitled Are you there God? It’s me, Žižek, and when Milbank waxes poetic about the Twilight movies—I wanted to engage some topics that would likely receive attention, were the authors to meet for drinks. Primarily, I envisioned an intense discussion of theological metaphysics, with Milbank emphasizing the importance of the logos asarkos (the Word without flesh), Barth defending his doctrine of election and talking up the logos ensarkos (the Word incarnate, Jesus Christ), and Žižek wondering whether contemporary debates are but symptoms of a secret puzzle, hidden deep within the Protestant tradition, about the relationship between Christology and the doctrine of the Trinity—a puzzle that is by definition unsolvable, a symptom of “the Real.”2 There would then follow remarks on the orthodoxy/heresy binary as it relates to theology and contemporary Marxism; comments on materialism, new forms of transnational religious militancy, and globalization; an animated discussion of the church, in which Barth and Žižek would speak up for a politicized ecclesiology and Milbank would ask Barth some difficult questions about the Eucharist; and, finally, a cameo for a discerning bartender, who, having challenged each thinker to speak plainly about sexism and heterosexism, finds herself appalled by their awkward responses. No doubt, my fictional interchange would not provoke much laughter. Although Žižek’s and Barth’s writings have genuinely humorous moments and Milbank’s hyperseriousness would provide an amusing contrast, there is little chance of this writer viably impersonating the thinkers and no prospect of his penning a winsome script. Still, a contribution of this sort might usefully signal what a profitable academic exchange should involve: a frank exchange of views, with each thinker refining his or her best insights, appreciating the legitimacy and cogency of others’ ideas, and recognizing that the truth can only be approximated, by the grace of God, in provisional and halting ways.

Given my inferior skills as a dramatist, then, as well as a lack of expertise with Žižek’s various works and an inability to inhabit a “radically orthodox” outlook, I am reduced to offering something more prosaic and less evenhanded. Using The Monstrosity of Christ: Paradox or Dialectic? as my principal text, my goal is to imagine what Barth might add to the conversation between Žižek and Milbank. My suggestion, in brief, is that Barth would urge both authors to take the monstrosity of Christ—that is, the nearly inconceivable and always mind-boggling claim that the divine “Word became flesh and lived among us” (John 1:14 RSV), and “bore our sins in his body on the cross, so that, free from righteousness, we might live for righteousness” (1 Pet. 2:24)—rather more seriously than they seem to do.

On one level, Barth would criticize the christological positions that Žižek and Milbank favor. Both authors err insofar as they fit Christ into preexisting theological or philosophical schemes, as opposed to considering him as the concrete, particular, and personal reality who determines theological reflection. On another level, the description of God, Christ, and the atonement in the later volumes of the Church Dogmatics supplies us with a more theologically vital perspective—that is, a perspective that is more intellectually compelling, more attuned to the scriptural witness, and more pertinent to the political moment in which we find ourselves—than either Žižek’s materialist Hegelianism or Milbank’s radically orthodox celebration of plenitude, paradox, and participation. No doubt, the contemporary authors contribute to theological reflection in valuable ways, and their willingness to admit frank disagreement across disciplinary lines is particularly salutary. But in my judgment, neither Milbank nor Žižek proffers an account of Christ that has the theological richness or political suggestiveness that distinguishes Barth’s later work.3

Before elucidating this rather partisan argument, three caveats are in order. First, I must ask readers’ indulgence for sidestepping a number of important issues, chief among which are Milbank’s assessment of medieval theology and its legacy; Žižek’s synthesis of Lacanian, Hegelian, and Marxist insights, as well as his forays into popular culture; both authors’ treatment of G. K. Chesterton, Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Schelling, Søren Kierkegaard, and others; and both authors’ views on Scripture, tradition, faith, reason, and providence. Second, Milbank’s and Žižek’s fondness for brash overstatements, dubious generalizations, and idiosyncratic modes of argumentation notwithstanding, in what follows I will do my best to avoid polemics. Certainly Milbank (to some degree) and Žižek (to an impressive degree) would defend their employment of hyperbole, just as Barth would defend the explosive language of the second edition of Der Römerbrief (1922).4 And some strong words are probably unavoidable when two authors engage in what Creston Davis, in his preface to The Monstrosity of Christ, describes as “the intellectual equivalent of Ultimate Fighting” (19)—although I’ll refrain from wondering why Davis believes that this academic exchange is comparable to testosterone-fuelled displays of violence, staged to entertain teenage boys. Yet my goal is to write and think in a more temperate way, taking both authors’ viewpoints as seriously as possible and endeavoring to imagine how Barth might respond. Third, I should admit straightaway that that this essay will not speculate as to a counter-counter-response. That is to say, I will not turn the dialectical tables once again and imagine what Žižek and Milbank would make of Barth’s sed contra. This is somewhat regrettable. It forestalls a substantive and critical consideration of Barth’s distinctive christological concentration (is it a live option for Žižek or Milbank, given their respective ecclesiologies?); it also risks discouraging much-needed critiques of Barth, developed from diverse theological, philosophical, and political positions. But a short essay cannot do everything. My concern, above all else, is to keep thought moving—to inject Barth’s voice into an important discussion that brings together Christian thought and the Marxist tradition, broadly conceived.

Monstrosity Diminished

Although Žižek’s professed concern in the opening essay of The Monstrosity of Christ is to tender a “modest plea for the Hegelian reading of Christianity,” readers will be unsurprised to learn that there is nothing remotely modest about his petition. What Žižek offers is a thoroughly materialist interpretation of Hegel: a perspective that twists Hegel from side to side, then turns him upside down and downside up, until all references to transcendence are utterly dialecticized and utterly de-substantialized. Any construal of Geist “as a kind of meta-Subject, a Mind,” in fact, is deemed a bad-faith attempt to make Hegel “a ridiculous spiritualist obscurantist” (60). Žižek views such construals, common though they may be, as erroneously supposing that finitude can be treated as a passing stage in the career of Geist: a failure to think about Spirit, mind, and matter in terms of their elemental and permanent co-implication. “Obscurantism” of this kind, moreover, is adjudged existentially and politically debilitating. Only as we inhabit a genuinely materialist perspective, which accepts finitude in all of its agonistic and negative complexity, do we become vehicles of Spirit and catch sight of a new kind of politics. Why so? Well, when we stare into the “abyss of the Spirit’s self-relating” and reckon seriously with nullity, we no longer aspire to “regain the lost innocence of Origins” (72). We abandon reliance on either a theological “big Other” (a transcendent deity who controls our destinies) or a political “big Other” (the party which, dependent upon a conveniently self-accrediting philosophy of history, presumes to occupy the vanguard and represent the proletariat). More positively, we begin to consider truly emancipatory courses of action. Dispossessed of a false totality and invigorated by a belief in “the ontological incompleteness of reality” (240, my emphasis), we move toward subject positions that recognize and, still more importantly, hold open the void that gapes before us. We discover new resources to contest, in innovative and effective ways, the often-savage operations of global capitalism.5

What does this curious reading of Hegel have to do with Christianity? More than one might think.6 Žižek’s philosophy of history—which, in good Hegelian fashion, is also a philosophy of human subjectivity—identifies Christ’s life and death as the decisive occasion for individual and collective maturation. Žižek believes, specifically, that the incarnation of the Son, understood in terms of the Father’s exhaustive kenotic finitization, releases us from thinking in terms of a transcendent deity who governs the course of history and controls our destinies. Because of Christ, we need no longer suppose that our relationship to God qua Father defines what we are (alienated) and what we may do with our lives (not much). Indeed, freed from such self-sabotaging ideological constructs, we are emboldened to consider futures of our own devising. Following the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ, there arises the community of Spirit—a new historical force, animated by the power that had previously been ascribed to the divine Other and cognizant of the fact that human beings, and human beings alone, have responsibility for history. Thus it is that the “universal God returns as a Spirit of the community of believers” (61, my emphasis) that recognizes materiality as a fundamental “given” but does not consider human life to be deterministically defined or insusceptible to revolutionary change. In brief, then: the incarnation of the Son means the death of the Father, the death of the Son means the advent of the Spirit, and the advent of the Spirit means an existential and political condition poised to imagine and effect a postcapitalist future.

One way of looking at this perspective is as a bold reconceptualization of the old adage O felix culpa! (“Oh fortunate fall!”) The fall is no longer construed in terms of Adam and Eve sinning against God; it is conceived in terms of the Father translating himself, without remainder, into the concrete life of the Son, whose death—the negation of negation—inaugurates the community of the Spirit. Redemption, concomitantly, is no longer something done to and for us (or even with us). It is a possibility that we must actualize for ourselves. Still more audaciously, Žižek is proposing that his reading of the Christian tradition become an integral part of the theoretical world of the left. A radically historicized construal of the Trinity and an appeal to the basal fact of the incarnation is an indispensable provocation for thought. It reveals a revolutionary freedom that lies beyond belief in the “big Other,” whether that “big Other” is conceived as a hypertranscendent dictator, faith in the inexorable march of history, or the disgraceful beauty of late modern capitalism; and it helps to generate the self-consciousness needed for the revolutionary class to “understand its historical mission” and begin “transforming society consciously.”7

The obvious question: What would Barth make of this? He would probably accept, first of all, that Žižek operates with some entrenched convictions, the likes of which cannot be broken down by frontal assault. That is to say, Barth would probably not open proceedings with an attack on Žižek’s supposition that human beings can shape the course of history, denouncing this as an intellectual misstep brought about by a surfeit of proud titanism, nor would he spend time bemoaning Žižek’s willful heterodoxy or his creative (mis)handling of the scriptural witness. In fact, Barth might well grant Žižek’s avant-garde materialism a prima facie cogency. Materialism of this sort may not be theologically desirable, but it is not logically impossible, intellectually incoherent, or ethically insufferable, and it cannot be summarily dismissed. It might even be deemed a “secular parable of the truth”—certainly it seems more philosophically interesting, and more politically vital, than most of what the “new atheists” have offered for discussion.8 Should Barth wish to challenge Žižek, then, he would perhaps begin with an immanent critique. He would pose a simple question, consonant with Barth’s own style of thought: Is Žižek sufficiently dialectical in his thinking?

Probably not. Milbank is right, I think, to identify Žižek’s frequent recourse to the category of “nullity” as reminiscent of a flatfooted natural theology: it ends up “deriving all subsequent rationality in an ordered series from pure nullity—as from pure divine simplicity—in such a way that all reality can be logically situated with respect to this nihil” (158). Indeed, granted that Milbank draws a too-hasty parallel between God qua “first cause” and a nullity that, for Žižek, is by definition not simple (or, for that matter, complex), he is on to something, and Barth would press the point. Nullity does seem to function as an irreducible “given” for Žižek, marking the terminus beyond which his antireductionistic materialism does not go. And if that is the case, it is not clear that reductionism has really been avoided. Can Žižek imagine, one might ask, what it might mean to continue the dialectical process and to negate the “negation of the negation” that is the unclosed materialism of the spiritual community? The question is a little cute, but not unfair. Although Žižek claims to propound a new kind of materialism, and although his appeal to Christ’s life and death as that which holds open the possibility of the “void” is intriguing, the dialectical turn that he does not consider is one brought about by an unforeseeable act of God—that is, the intrusive workings of a deity who cannot be preemptively thought of as the “big Other,” a God who escapes the binaries of mundane existence and who confronts, judges, and redeems humankind.

To turn the knife somewhat, Barth might next draw on Ludwig Feuerbach’s famous critique of Christianity. Is Žižek doing theology here, or is he actually promoting a problematic kind of “religiosity”?9 Certainly, it might be the former—theologians do not speak sub specie aeternitatis and should beware of hasty denunciations—but it could well be the latter. Such religiosity may not be akin to that of the cultured Prussian (the bourgeois patriot, quick to support military ventures and eager to extol the glories of nation, blood, and soil, who Barth critiqued in the 1910s).10 It may be a religiosity of a new kind, one that objectifies an internally felt hollowness, nurtured by frustrated revolutionary aspirations, the uncanny ebbs and flows of desire, and the strange transience of life in privileged quarters of the “first world,” in order to play—and only play—at radical politics. And is not such religiosity vividly expressed when Christ is figured as a clown, a figure that suggests that when this “abyss speaks,” one does not hear the bold proclamations of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, but rather the lonely voice of an enfeebled political bystander? It may even be that the figure of the clown reflects something of Žižek’s own identity as an academic celebrity, an identity that, to some degree, has been foisted upon him by an academy that hankers after alternatives to mainstream “liberalism” but lacks the stomach for genuinely disruptive left-wing politics. What else, after all, can we imagine but the slapstick mischief of the circus when the revolutionary potential of “the Real” falls from view, being wholly “disappeared” by the global forces of capital?11

Milbank’s response to Žižek is characteristically uncompromising and continuous with the line of analysis elucidated in Theology and Social Theory.12 He detects in his conversation partner a style of thought that gained currency in the late middle ages and that continues to afflict theology today: a “univocalist, voluntarist, nominalistically equivocal, and arcanely Gnostic” (218) vision that distorts the Christian tradition’s best insights. As an alternative, Milbank commends a participatory metaphysics, anchored in the abundance of the Holy Trinity. Against dialectical conflict, he favors an acclamation of paradoxical harmony; against the givenness of materiality, a creation saturated with transcendence; against Christ as a “vanishing mediator,” a living Word who enlivens the sacramental life of the church; against Protestant atheism, an “authentic Middle Epoch” (218) in which faith and reason unite and “catholic” societies anticipate God’s peaceable kingdom.

The way Milbank elaborates this position is intriguing. On one level, he appeals to a “transgeneric vision” (172) that discerns the underlying harmony of creation. Given that our common experience is not a matter of “random and aporetic contingent finitude” (115, emphasis removed), there is no warrant for Hegel’s ontologization of contradiction nor justification for an appeal to Žižek’s dialectically imaginable, yet ontologically elusive, “Real.” The complex world in which we live invites a different assessment, for its “pleasing harmony” (164) adverts to a “framing transcendent reality” (166). One finds here, in other words, a reading of experience keyed to God’s loving, creative work: a celebration of the fact that “ever since the creation of the world his eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the things he has made” (Rom. 1:20). On another level, in line with Thomas Aquinas, Milbank argues that God’s revealed triune identity enables us to know who sustains creation and moves it toward a glorious end. Indeed, given that Christians understand the Father, Son, and Spirit to enjoy a paradoxical relationship of unity and difference (“paradoxical” in the sense that this relationship exceeds anything conceivable through kenotic and/or dialectical rationality), they can avoid Hegel’s mistakes and engage the world as it truly is: an “embodied plentitude” (138), grounded in the triune God’s illimitable beneficence, that awaits our fitting responses.

The incarnation makes such engagement with the world a live option. Although sin disorders desire and warps perception, Christ graciously reveals the identity of the God who precedes and defines all things and who shapes human activity in ways that accord with God’s providential design. Christ’s saving work, more particularly, has both cosmic and moral dimensions, for “the entry of the infinite into the finite and the paradoxical identification of the infinite with the finite” (212) enables clarity of sight and heals wills for the purpose of forgiveness and peacemaking. And the cross? Granted that the cross is the glorious conclusion of Christ’s revelation of harmony and the crowning moment in the life of the One who orients finitude toward the triune God, its dogmatic significance should not be overstated. Žižek is certainly wrong to suppose that it amounts to a decisive moment of divine self-emptying, such that a new kind of political community can emerge. For Milbank, it is because of the whole of Christ’s life—“one specific finite moment . . . of absolute infinite significance, beyond all human imaginings” (215)—that we know that God has committed himself to us and will bring about our salvation. We know, too, that a Christian community’s political labors ought to be coextensive with its participation in God’s work, the principal mediation of which is the Eucharist. For when the living Christ is truly acclaimed and celebrated, the divine order is made manifest, the giving of gifts has no end, and the church performatively anticipates an eschatological joy that the prophets of nihilism cannot possibly foresee.

Barth could surely respond vigorously to various elements of Milbank’s proposal. He would dispute many of Milbank’s historical judgments and offer a strong defense of the magisterial reformers; he would ask probing questions about Scripture and the analogia entis (“analogy of being”); he would worry greatly, I think, about the paternalistic dimensions of Milbank’s position. But I want to keep in touch with my earlier criticisms of Žižek and pose only one question on Barth’s behalf: Is Milbank’s statement in The Monstrosity of Christ also susceptible to Feuerbachian critique?

I think so. Milbank’s remarks, in fact, seem ready-made for a Barth-inspired version of ideology critique. It all seems a bit too religiously intoxicating. When Milbank offers a Hopkinsesque description of a car journey by the River Trent, undertaken alone, in which “[e]verything is univocally bathed in a beautiful, faintly luminous vagueness, tinged at its heart with silver” (160), in which the mysterious interplay of a river, roofs, spires, and a winding road delight author and reader alike . . . Well, it requires little effort to imagine Barth’s response. Do we really want to give experiences of this kind a place in theological reflection? Do we not find here a rhapsodic universalization of a particular standpoint—a quintessentially “Anglo-Saxon” one, to boot, albeit of a romantic and decidedly middle-class sort—that distracts attention from the scriptural record that ought to direct thought?

Barth’s concerns would compound, were he to consider how Milbank’s experiential reflections dovetail with his treatment of the incarnation and the Trinity. On one level, Barth would note, perhaps somewhat mischievously, certain points of connection between Milbank and the younger Friedrich Schleiermacher.13 Certainly the so-called founder of modern Protestant theology did not see “Christ’s human existence [as] entirely derived from the divine person of the Logos by which he is enhypostasized” (210) in his early writings. Yet, much like Milbank, Schleiermacher supposed Christ to be the one who reveals to us, and thereby makes thinkable and experienceable, the coincidence of finite and infinite. Schleiermacher, too, was rather reluctant to construe Christ’s death-in-abandonment as the all-important culmination of his identity, the decisive pivot around which salvation turns, preferring to view “the ‘perfect suffering’ of the Cross” as “but one aspect of an entire action whereby the finite is restored to full existence in time through its paradoxical conjunction with the infinite” (212, my emphasis).14 And Schleiermacher, too, thought primarily in terms of the exemplary life of Christ transforming our religious consciousness, invigorating our sense of creation’s harmony, prompting the formation of intensely relational church communities, and spurring progressive political activity.

On another level, Barth would ask: What vision of the Trinity is invoked here? Milbank’s account of the divine life—a “realm of fantastic pure play” (186) in which love circulates ceaselessly and dialectical agonism has no place—is certainly a dogmatic tour de force. This reworking of insights drawn from Gregory of Nyssa, Augustine of Hippo, Thomas Aquinas, and (to a lesser extent) Meister Eckhart and Nicholas of Cusa supports a doctrine of God that fits snugly with an understanding of creation organized around the categories of harmony, relationality, plenitude, and gift; it shows how a richly textured experiential faith might dovetail with insights drawn from patristic and medieval theologians. But could it be that just as Žižek cannot look beyond nullity, Milbank is stuck with an understanding of God controlled by contestable presumptions about impassibility and transcendence? More sharply, is it not possible that Milbank writes so lyrically about God’s “infinite relating” because he projects what he perceives as the gentle harmony of creation onto a theological screen, as opposed to thinking about God in light of God’s self-revelation? And could it be that this very projection leads Milbank to hold the hard realities of Christ’s life, suffering, and death at too much of a distance from God’s immanent being?

This last question is perhaps the most important of all. Although Milbank’s God participates in the world in a thoroughgoing way, this God does not ever open himself to the ambiguity, sinfulness, and suffering of the creation of which he is Lord. At every point, God remains serene and untroubled: the infinite is “in” the finite, but in no respect does any portion of finitude affect God’s infinite triune relating. Consequently, God’s solidarity with us, understood in light of the life and death of Jesus Christ, is downplayed to a worrisome extent. Milbank will not allow even the slightest “particula veri in the teaching of the early Patripassians” (CD IV/2, 357), for he will not imagine a doctrine of the Trinity that, in a radical way, takes it bearings from the incarnation. Or to put it in terms that Barth favors, Milbank does not think in terms of God freely determining himself, as Son, as one who suffers with us and on our behalf. As such, Milbank cannot conceive of what Barth would adjudge to be truly “monstrous” for thought: the divine Son becoming and being flesh, submitting himself to the rejection that sinners deserve, electing himself to be Christ crucified.

Monstrosity Rethought

Thus far, Barth’s imagined contribution to the Žižek/Milbank debate has been quite critical. With respect to Žižek, I have suggested that Barth might develop an immanent critique and ask whether “today’s forms of radical scientific materialism” really “keep the spirit of infinity alive” (242). Žižek’s own materialism, it seems, is less open than he would have us suppose: a fascination with nullity effectively rules out a dialectical negation of materialism and blocks any thought of the intrusive, liberative work of God as the “One who loves in freedom.”15 And this, in turn, raises a crucial question: Is Žižek’s materialist Christology less a way to think novelly about the Real and more the projection of a subject allured and frustrated by the apparently unassailable ascendancy of global capitalism? With respect to Milbank, Barth would dispute the appeal to experience and worry about the metaphysical moves that accompany it. Indeed, if Žižek fails to think beyond nullity, Milbank fails to imagine a theology that avoids an unhelpful binary: either an immanent Trinity of “pure play,” wholly untouched by the world, or a completely historicized and materialized economic Trinity. Milbank therefore never considers the possibility that God establishes a limited kind of “real relationship” between God and creation in the person of Christ; he never explores the idea, more specifically, that God sovereignly intends for the concretely lived history of the Son to bear upon the Son’s eternal being. And, perhaps not coincidentally, given his reluctance to dwell on the unlovely reality of Christ crucified, the upshot is a fairly lackluster account of atonement. Milbank focuses less on what P. T. Forsyth memorably styled the “cruciality of the cross”16 and more on Christ’s restorative exhibition of the gloriously paradoxical relationship of creature and Creator.

Put bluntly, neither Žižek nor Milbank describe Christ in especially monstrous terms. There is little to disrupt the intellectual and political status quo, given that both authors fit their Christologies into preexisting schemes of thought (a neo-Marxist reading of Hegel, on the one hand; a radically orthodox metaphysics, on the other). In fact, these schemes of thought, beyond being susceptible to Feuerbachian critique, effectively limit what might be said about God, Christ, and radical politics.17

What would it mean to take the monstrosity of Christ seriously in light of the Milbank/Žižek debate? Since Barth does not pose this question, we do now enter the realm of conjecture. It is also important to note straightaway that my account of Barth’s theology—which, as will become clear, focuses on Church Dogmatics II/2 and subsequent part-volumes—depends on some interpretative judgments that require a lengthier defense than can be provided in this context. However, given that neither Milbank nor Žižek want shrinking violets for conversation partners, and given that I have offered a fuller statement about Barth’s theology elsewhere, there is no need for reticence.18 Barth’s positive account of Christ’s monstrosity, I want to suggest, would likely involve three moves, which I will only sketch: (a) a “post-metaphysical” account of the Trinity, developed in light of Christ’s concrete history, that supports a flexible theological materialism; (b) a political theology that focuses on human “being in becoming” as well as divine “being in becoming”; and (c) an understanding of atonement that presents Christ’s death as central to our salvation and indicative of that which we often want to deny—the tragedy of sin and the victory of grace.

To consider the Trinity in light of Christ’s concrete history, so far as Barth is concerned, requires that theologians do more than draw connections between discrete dogmatic loci and thereby signal compatibility between their account of God and their description of Christ’s person and work. At issue here is the conviction that the actual, concrete, and personal history of Jesus Christ—that is, the life, death, and resurrection of the rabbi from Nazareth, narrated in the canonical Gospels—has a direct bearing on the being of God qua Son. This is what it means, in fact, to say that Jesus Christ is the “electing God” and the “elected human.”19 God has sovereignly decided upon an identity, as Son, that is irrevocably bound to, and in some way funded and constituted by, the lived history of Jesus of Nazareth.20 Now this, I hurry to add, is not a decision that God is required to make. It is also not a decision that, à la Hegel and Žižek, collapses the immanent Trinity into the economic Trinity, with the result that God’s being is controlled by historical events. The point is rather that God assigns himself, as Son, an identity that is eternally inclusive of the embodied and concrete history lived out by Jesus. Or to put it a bit differently, God is Lord over God’s being to the point at which God’s freely deciding to become the enfleshed Word coincides with the Word of God being enfleshed, being Jesus Christ, for all eternity. To think along these lines might be rather dizzying, but that is no reason for undue caution: dogmatics is not in the business of rendering God familiar. There is here a starting point for a highly actualistic, “post-metaphysical” doctrine of God, an attempt to think of Exodus 3:14, John 1:1–18, and Acts 2:33 simultaneously.21

Consider now what this means for the Žižek/Milbank debate. Generally, one need no longer treat the immanent Trinity/economic Trinity distinction as an unyielding binary. For sure, the distinction has utility. Talk about the immanent Trinity emphasizes the priority of God’s being: it signals that God’s life is (infinitely) more than God’s relating to humankind and underscores that the incarnation has as its condition of possibility God’s unlimited, transcendent sovereignty. Talk about the economic Trinity ensures that the creative, reconciliatory, and redemptive actions of God that Scripture narrates have their ground in, and are deemed suitably revelatory of, God’s eternal being, while not being considered exhaustive of that being. But the distinction ought not to be reified to the point at which God’s freedom to define Godself is underrated or obscured. Indeed, if one disavows a crude disjunction between the immanent and economic Trinity, one is freed up to posit an ontologically significant connection between the history enacted by the incarnate Son and the being of the Son. To draw on Eberhard Jüngel’s phraseology, since, for all eternity, God sovereignly determines to become and be, as Son, the concrete person of Jesus Christ, the logos asarkos is always becoming and being the logos ensarkos.22

This understanding of God and Christ, moreover, supplies the foundation upon which a christologically defined theological materialism can be built. Because of a sovereign, elective decision, made “before the foundation of the world” (Eph. 1:4), the embodied history of the man Jesus is a permanent feature of the divine life. This, ultimately, is what Barth means when he writes that the “obedience of Jesus Christ as such, fulfilled in that astonishing form . . . is a matter of the mystery of the inner being of God as the being of the Son in relation to the Father” (CD IV/1, 177) and insists that Christians must therefore “correct our notions of the being of God,” even “reconstitute them” (CD IV/1, 186). In view of Christ’s history, we begin to think beyond the “pure play” of the divine persons; we discover a divine perfection defined by God’s opening of Godself to the lived, embodied history of the Word. The fullness of divinity and the fullness of human physicality can be imagined to coincide in time and (divine) eternity, in the person of the Son; by the grace of God, these opposites, separated by an “infinite qualitative difference,” are always-already held together (but not confused, much less made of equal value). By extension, materiality as such, and more particularly the life of each human, receives a remarkable kind of dignity. Because the “atonement is history” (CD IV/1, 157), we know that God’s openness to the concrete person of Christ is paired with Christ’s openness to humanity. Christ accepts us as we are; he, the “firstborn of all creation” (Col. 1:15) envelops the people whose head he is. Consequently, humanity as such—that is, humanity in all of its wondrous, diverse, and sometimes awkward corporeality—is set before God the Father as a sanctified and redeemed creation. Christ’s intercession on our behalf carries in its wake an affirmation of human (and perhaps nonhuman) bodies as unsublatable elements of the creation that God affirms, enjoys, and wills to save.

When one begins to theologize in this way, some interesting ethical and political possibilities also come into view. On a general level, because Christ is God’s definitive statement about the value of human life and because we are charged to live as valued members of his body, it follows that Christian ethics includes a forthright affirmation of human rights. The rhetoric used by theologians might, on occasion, differ from that employed by their “secular” colleagues, but the gist of their positions will be welcomed: because God has affirmed the preciousness of human beings, we must do likewise. On a more particular level, because God reveals Godself as a “being in becoming” who is open to ontological difference (that is, the difference of the human Jesus), Christians are emboldened to affirm various forms of human “being in becoming.” Situated in and defined by a Word who becomes, Christians are given a new kind of liberty and begin to recognize and delight in difference and transformation—even in certain forms of individual and collective experimentation—that honor the liberated future toward which we are being moved. What one finds here, in fact, is what Milbank and Žižek rightly identify as fundamental for radical politics today: a theological ontology and anthropology that supports progressive political theory and encourages various kinds of political action. True, a loose analogy is at work. There is a huge difference between the self-constitution of the divine Son and the “opened” horizons that accommodate diverse forms of human flourishing. Yet there is no need for a strong analogy. My contention is simply that the obvious plasticity of human life, productive of an ever-expanding array of individual and collective identities, is comprehensible—or, even better, affirmable—when one accepts that we are made in the image of the God who, as Son, freely transforms himself, becoming and being what he need not be.23

And whereas Barth sometimes failed to think consistently about what it means to say that the human being is “set in motion from its very center by the act of the Subject who exists here” (CD IV/2, 29), falling victim to outmoded and damaging claims about sex, gender, and sexuality, the interpretative line that I am pursuing affords us an opportunity to correct his mistakes. We can update the indirect but insistent democratic socialism of the Church Dogmatics with a fuller understanding of oppression—one that, among other things, complements Marx’s insights with an analysis of sexism and heterosexism and brings Barth into conversation with those who struggle for women’s rights and the rights of the queer community. Žižek’s worries notwithstanding, the “politics of identity”—that is, mostly laudable attempts to expose and overturn an array of viciously discriminatory conventions—can and should go hand-in-hand with critiques of economic injustice.24

Does this exhaust what might be said about the monstrosity of Christ? Not yet. Thus far, we have only what is “monstrous” for the doctrine of God (a God who determines himself, as Son, in terms of Christ’s concrete history) and what is “monstrous” for a politically charged theological anthropology (an understanding of the human that recognizes that we, too, are “beings in becoming”). Barth presses us to take another step and to recognize Christ’s monstrosity in terms of his burdening himself with the nearly unbearable weight of human sin.

God’s love for humankind, Barth believes, means more than the Son becoming human. It means the Word becoming flesh, disposing himself as one who undergoes judgment. It means, even more dramatically, that Christ freely takes upon himself the wrongdoing of others, even as his own conduct proves irreproachable. As Christ sets his face toward Jerusalem, as his disciples forsake him and the elites of the day conspire against him, his solidarity with sinners becomes ever more intensive, ever more thoroughgoing—so much so that his being made “in the likeness of sinful flesh” (Rom. 8:3) culminates in his being the one who “bore our sins in his body on the cross” (1 Pet. 2:24) to the bitterest of ends.25

Christ’s life is therefore both kenotic (as Žižek wishes it to be) and glorious (as Milbank wishes it to be). It is kenotic because Christ does not maintain his distance from his enemies, holding fast to an identity that stands aloof from their sinful machinations. Instead, he opens himself to the schemes of those arrayed against him. He allows himself to be defined by others; he accepts their wrongdoing; he exposes our sinfulness, past, present, and future for what it is—an attack on God and God’s gracious ways and works—when he dies on Calvary. (He “did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited but emptied himself . . . and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross” [Phil. 2:6 and 2:8]). Christ’s life is glorious because, in the same moment that he is subjected to the wickedness of his enemies, he endorses God’s judgment upon sin and releases God’s boundless love once more. Insofar as he disposes himself as the true representative of sinful humankind (one who takes our wrongdoing upon himself) and the sole substitute for sinful humankind (one who endures the punishment that we deserve), that which obstructs God’s love is now finished. Indeed, precisely because he “made our sin His own” (CD IV/1, 241), precisely because he offers what must not be to God, God is able to do “that which is ‘satisfactory’ or sufficient in the victorious fighting of sin.” God brings about a “victory” that is both “radical and total” (CD IV/1, 254); God kills off the sin that we commit and carries us, in the body of the risen Christ, toward a redeemed condition. Put a bit differently: granted that, by way of the cross, God says an unequivocal no to human wickedness and accepts the awful sacrifice of God’s only-begotten Son—a sacrifice that is itself humanity’s endorsement of God’s rejection of sin—God’s yes to humankind is spoken anew with unparalleled force and clarity when Christ is raised from the dead by the Father, in the Spirit.

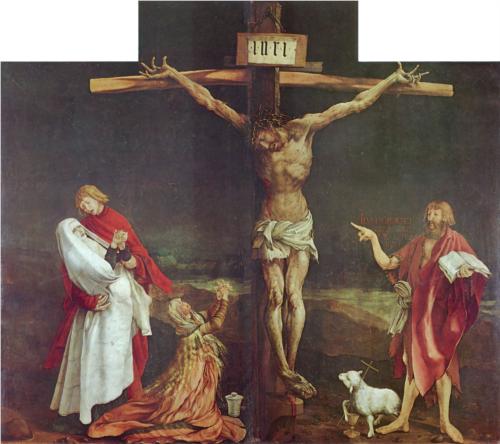

The monstrosity of Christ crucified, then, cannot be thought apart from the monstrosity of sin. Our unfailing faithlessness, our petty and not so petty falseness, our abiding cruelty, our intolerable sloth and boundless stupidity: this is what we behold when Christ dies. As we look upon the figure of the crucified rabbi, we learn about sin’s deathly wage. Still more monstrous, however, is the fact that the full weight of human wrongdoing is borne, lovingly and freely, by Christ. To make the point in a way that Barth would surely approve, the outstretched finger of John the Baptist, powerfully depicted in Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim altarpiece, accuses me of monstrosity, just as it accuses you; it reveals God’s rejection of our hate-filled efforts to impede the communication and circulation of love. Yet accusation and rejection is not the whole story. At the foot of the cross stands Christ’s mother, Mary Magdalene, the Beloved Disciple, and John the Baptist: four individuals who already know something of a grace that overcomes sin, acquits us of guilt, assures us of a joyous redemption, and pushes us to move, ecclesially and politically, toward the kingdom. And the implicit counterpoint to their grief is the joy of the resurrection—that mysterious public declaration of God’s determination to move beyond a mere declaration of forgiveness and to bring every human being into the closest possible union with God, in Christ, through the Spirit. Christ has “borne the consequence of [our] separation” from God in order “to bear it away” (CD IV/1, 247), and what follows is the ramifying of Christ’s resurrection: a gradual and often imperceptible conforming of all human life to a future in which God’s will on earth is truly done. It seems unbelievable, it seems politically impossible, it seems more unlikely with each passing moment, but it is a truth that Barth will not and cannot repress: the monstrosity of sin is overtaken by the monstrosity of grace. The political task before us, then, is to honor this truth in the most concrete terms, to realize the liberating promise that God declares to be our future, and to “revolt against disorder . . . going to meet the coming kingdom of God, by seeing and grasping the possibilities which are provisionally present or which offer themselves not for divine but for human righteousness and order.”26

1. This essay is adapted from a chapter in the forthcoming volume, Karl Barth in Conversation, ed. Travis McMaken and David W. Congdon (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock).

2. A statement from Jacques Lacan’s “Seminar on ‘The Purloined Letter’” is relevant here: “the real, whatever upheaval we subject it to, is always and in every case in its place; it carries its place stuck to the sole of its shoe, there being nothing that can exile it from it” (Lacan, Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink with Héloïse Fink and Russell Grigg (New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 2005), 17. In Žižek’s rendering, “the Real” is that which is not absorbed by diverse patterns of hegemonic thought and diverse material processes: a site of alterity that stimulates liberative political action.

3. Quotations from the works under consideration—Slavoj Žižek and John Milbank, The Monstrosity of Christ: Paradox or Dialectic, ed. Creston Davis (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009); and Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, various translators, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (London, UK: T&T Clark, 2009)—are set in the main body of the text. Page numbers are used to refer to The Monstrosity of Christ, whereas the letters CD are followed by Roman numerals to denote quotations from the relevant volume and part-volume of the Church Dogmatics. For ease of reference, page numbers for the Church Dogmatics refer to the standard English translation.

4. On this issue see Jones, “The Rhetoric of War in Karl Barth’s Epistle to the Romans: A Theological Analysis,” Journal for the History of Modern Theology / Zeitschrift für Neuere Theologiegeschichte 17.1 (2010): 90–111. Also of interest is Stephen H. Webb, Refiguring Theology: The Rhetoric of Karl Barth (Albany, NY: SUNY, 1991).

5. As Friedrich Nietzsche’s Zarathustra says, “Hail to me! You are coming—I hear you! My abyss speaks, I have unfolded my ultimate depth to the light!” So Thus Spoke Zarathustra, ed. Adrian Del Caro and Robert B. Pippin, trans. Adrian Del Caro (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 174. Žižek’s project might be construed as a politicized outworking of this clutch of exclamations: an insistence that a certain kind of nihilism, when mixed with idiosyncratic interpretations of Karl Marx, Jacques Lacan, and G. W. F. Hegel, offers a promising opportunity for disrupting twenty-first-century capitalism.

6. In exploring Žižek’s work in relation to Christian theology, I have learned much from Adam Kotsko, Žižek and Theology (London, UK: T&T Clark, 2008) and Marcus Pound, Žižek: A (very) Critical Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008). I have also profited from Cyril O’Regan, “Žižek and Milbank and the Hegelian Death of God,” Modern Theology 26.2 (2010): 278–86.

7. Georg Lukács, History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectic, trans. Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, n.d.), 70 and 71. Emphases altered.

8. For more on “secular parables,” see the epilogue to George Hunsinger’s pioneering text, How to Read Karl Barth: The Shape of His Theology (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1993), 234–80.

9. For Barth’s mature account of “religion,” see CD I/2, §17 (280–361). See also, of course, Feuerbach, The Essence of Christianity, trans. George Eliot (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1989).

10. As is well known, Barth was dismayed to discover many of his former teachers supporting Germany’s efforts in the Great War. In 1914, writing to Martin Rade, Barth lamented how “love of the Fatherland, enjoyment of war, and Christian faith” could be thrown into “hopeless confusion” (Barth, Offene Briefe, ed. Diether Koch [Zurich, Switzerland: TVZ, 2001], 27).

11. A suitably Žižekian illustration of this point is one of the finest North American films of the late 1970s, scripted by Jerzy Kosinski and based on his own novella: Being There (directed by Hal Ashby, 1979). At the end of this film, the clueless star of the drama (played brilliantly by Peter Sellers) has been thoroughly transformed. He is no longer Chance the gardener, rendered destitute by the death of the old man whose property he helped to maintain. Through various twists of fate and luck, a political culture defined by abject superficiality, and the misguided patronage of a dying business magnate, he is now the sophisticated Chauncey Gardiner: Shirley MacLaine’s avant-garde lover, a respected intellectual force in Washington, DC, the heir to a massive fortune, and likely the next president of the United States. Could it be, then, that an unwitting clown—someone who walks on water at the end of the film, which suggests something significant about the “old man” whose garden he tended—is poised to effect real change? Well, no. Chance/Chauncey will in fact have no political impact, not least because corporate plutocrats organize his ascension to the presidency in order to maintain the status quo. Might there follow some kind of moral transformation in those same plutocrats, though, given Chance/Chauncey’s unwittingly profound/obviously banal remarks? Again, no. Were the narrative to continue, the only outcome would be for this “clown” to be exposed for what he is—a mentally limited man who is obsessed with bad television—and then subjected to a political “crucifixion,” unaccompanied by any resurrection. Why suppose, then, that a political theology that construes Christ in analogous terms will achieve anything more? It risks encouraging activism that lacks significance beyond the comedic; it supports forms of political theater that amuse those who recognize capitalism’s faults but struggles to promote much in the way of substantive social, economic, or political change.

12. See Milbank, Theology and Social Theory: Beyond Secular Reason (Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1993).

13. See here Schleiermacher, On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers, ed. Richard Crouter (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996), esp. 120–21.

14. For sure, neither Milbank nor Schleiermacher make the incautious claims of Alain Badiou—that “death cannot be the operation of salvation” and that “the Christ-event is nothing but resurrection” (Saint Paul: The Foundation of Universalism, trans. Ray Brassier [Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003], 70 and 73). In addition to their respective emphases on resurrection and a shared sense of the Christ as a person and community-forming power, both Milbank and Schleiermacher take seriously Christ’s ministry and grant some significance to his death. Yet neither dwell overlong on the saving effects of Christ’s death, and in both one finds an intriguing anticipation of Badiou’s creative misreading of Paul.

15. See here CD II/1, §28 (257–350).

16. See here Forsyth, The Cruciality of the Cross (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1997).

17. I am of course not suggesting that Barth’s theology is unaffected by philosophical influences, much less that it is the be-all and end-all of dogmatic work. All theological work bears the marks of its context, and Barth’s is no exception. Barth himself was fully aware of this, thus his early remark that “[o]f none of us is it true that we do not mix the gospel with philosophy” (Göttingen Dogmatics: Instruction in the Christian Religion, vol. 1, ed. Hannelotte Reiffen, trans. G. W. Bromiley [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1991], 259). Equally, Barth had an unwavering insistence that the relative truth of theological statements, if there be such a thing, is a matter of God’s gracious superintendence of our broken language—and not the talents of any given thinker, no matter how celebrated he or she might be. The question I want to press, rather, is this: In the final analysis, what directs the theological programs of Barth, Žižek, and Milbank? My answer, simply put, is that Barth’s theology succeeds, and provides an impressive goad for thought today, because of the relatively consistent way in which it derives theological claims from the concrete personal reality of Jesus Christ, whose history is mediated to us by way of Scripture—and not from abstract schemes of thought. This does not mean, again, that Barth is rendered immune from criticism, given his conscious or unwitting acceptance of certain philosophical mores. Nor does it mean that Milbank and Žižek should be deemed theological personae non gratae. But the point still holds. The distinction of Barth’s theology is its unflagging determination to follow, to “think after” (nachdenken) Jesus of Nazareth, the Word incarnate. The work of Milbank and Žižek, by contrast, often seems guided by metaphysical commitments that stand aloof from and prior to the scriptural witness to Christ’s person and work. He is not the animating center of their respective viewpoints; he is an illustrative symptom of those viewpoints. He is not the “monster” in terms of whom they think; his monstrosity is a function of their general descriptions of reality.

18. Jones, The Humanity of Christ: Christology in Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics (London, UK: T&T Clark, 2008).

19. See here esp. CD II/2, §33 (94–194).

20. In addition to the differences between the authors under discussion, it is worth noting that Barth and Badiou diverge dramatically. Badiou will say that “we need retain of Christ only what ordains this destiny [that of the ‘new creature’], which is indifferent to the particularities of the living person: Jesus is resurrected; nothing else matters, so that Jesus becomes like an anonymous variable, a ‘someone’ devoid of predicative traits, entirely absorbed by his resurrection” (St. Paul, 63). Barth takes the opposite position, albeit with Rudolf Bultmann, not Badiou, as his conversation partner. Because it is exactly the “particularities of the living” person that God embraces as constitutive of the identity of the Son, the Christian theologian is expressly forbidden from viewing the resurrection in such a way that the cross is “absorbed” and rendered ontologically passé.

21. For more on these issues, see especially Bruce L. McCormack, Orthodox and Modern: Studies in the Theology of Karl Barth (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008), 183–277. Among the challenges to McCormack’s reading of Barth, George Hunsinger’s essay, “Election and the Trinity: Twenty-Five Theses on the Theology of Karl Barth,” Modern Theology 24, no. 2 (2008): 179–98, strikes me as most valuable. As is probably apparent to readers familiar with debates over Barth’s view of election, my position has most in common with McCormack’s, even granted some differences.

22. See here Jüngel, God’s Being is in Becoming: The Trinitarian Being of God in the Theology of Karl Barth, trans. John Webster (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001).

23. This construal of human “plasticity” has various points of connection with certain claims in Kathryn Tanner’s recent work, Christ the Key (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010). Tanner and my/Barth’s dogmatic frameworks differ at key points, but our theological anthropologies appear to end up in similar places.

24. In a wonderful pair of sentences, Gerard Loughlin writes: “Queer seeks to outwit identity. It serves those who find themselves and others to be other than the characters prescribed by an identity” (“Introduction: The End of Sex,” in Queer Theology: Rethinking the Western Body, ed. Loughlin [Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 2007], 9). I am making a similar point to Loughlin, albeit from a different dogmatic position: my concern is to update, correct, and expand Barth’s theological anthropology by way of his doctrine of election in order to ground a liberative theological ethics.

25. Although it is right to say that the cry of dereliction is “the uttermost cry of faith,” it is not quite enough to say that it is offered “at the edge of nothingness” (Richard H. Niebuhr, Faith on Earth: An Inquiry into the Structure of Human Faith, ed. Niebuhr [New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989], 96). The situation is much more dire. Christ’s words are spoken in face of nothingness—that is, the full weight of sin and God’s judgment against it—and they express the condition of one who is encompassed and overwhelmed, if only for a moment, by that same nothingness.

26. Barth, The Christian Life: Church Dogmatics Volume IV, Part 4: Lecture Fragments, trans. Geoffrey Bromiley (London, UK: T&T Clark, 2004), 212-3. My emphasis.