1.

I found besides a large account book, which, when opened hopefully, turned out to my infinite consternation to be filled with verses–page after page of rhymed doggerel of a jovial and improper character, written in the minutest hand I ever did see.

—Joseph Conrad

“We’re buying gold for cash,” he says one night, from the crowded stage at Sharkey’s. Several people laugh, but several others approach him after the set about possible sales.

“I have a gold allergy,” explains a woman as she hands over a thin ring to the performer who spoke from the stage. He examines it under a light bulb.

“You get rashes from gold,” he says. She agrees, and walks away with one hundred and fifty dollars in cash.

“I stole this from my aunt,” says one young man, showing him a chain necklace. “But she deserved it.”

“Is that a joke?” says the performer, still sweating from his exertions. He drinks a glass of water while he considers the offer.

We end up next to each other in the bathroom, urinating into the same long trough. I stare straight forward at the band stickers and spidery scrawl covering the wall, but out of the corner of my eye see him turn to look at me.

“You play trumpet,” he says. “And your name is Alex.”

“I don’t anymore, but that’s still my name,” I say, fixating on an obscene message on the wall.

Apparently, the band I played with some years before had made quite an impression on him as a youth. He speaks of sneaking into a jazz club to see us perform. He remembers us arguing with the club’s agent about our compensation for the night. We shake hands after washing.

“Back in the day,” writes local author J. F. Hong in his memoir, A Life of Holes, on pool halls, billiard tables, and the personalities that made use of them, “Sharkey’s was the place to see rich socialites lose big money to common laborers, until a Chinese drifter used a serrated knife on a singer whose melodies he found distasteful.”1

Only after I remember this episode from Hong’s book do I recognize my new acquaintance: his band had gained press, at least minor press, over the last six months after he, Jorge, received a bruising for selling records and petty crafts at someone else’s show.

He and I exchange information about our current jobs and, one way or another, end up talking about tax season.

“It’s killing me,” he says. “Too many moving parts. Would you consider taking a look at the forms for me?”

I warn him, as we walk back into Sharkey’s bar area, that although I work as a civil servant, in a minor office of a minor branch of the local government, my knowledge of taxes and accounting is limited to my own finances.

“No,” he says. “You’re the guy for this.”

The stage lights change from red to green to blue.

The next morning at breakfast I wonder if I’ve performed an error in agreeing to Jorge’s request. Breakfast and dinner, for the tenants of my building, are prepared by the landlady, Madame Yu, and her two daughters. Strictly, this is not part of the lease. She and her daughters keep tabs and deliver bills at the end of the month to each tenant, who may then roll the payment into the next month’s rent check. We, the tenants, wonder, privately, how she and her daughters are able to wake in time to cook breakfast. Their apartment, on the ground floor, is often loud and lit all through the night as strange figures pass in and out to play mahjong. Nevertheless, even after a night of drinking and gambling, they prepare the meal by the time any of us are up.

After the previous night, it is hard to not read my cookie’s fortune as an omen: “New customs end in strange company.”

This fortune is still on my mind when I walk to Jorge’s apartment after work. The sun is low in the sky, low enough to appear beneath the clouds. I pause for several minutes to look down the hill at the light on the harbor.

Instead of meeting me at the entrance, Jorge drops a key out the window and yells out the number of his apartment, 308. The first staircase I try is blocked off with caution tape, not to indicate a crime scene but to indicate two missing steps. At the very back of the building is a second set of stairs that I climb to Jorge’s floor.

“I understand now why you dropped the keys,” I say.

“Two months,” he says. “We’ve been waiting two months for a repair. Every few weeks one of us will get sick of it, cut the tape, and jump the gap. After a day or two, the tape’s back up.”

Jorge spends some time offering a tour of his one bedroom apartment as well as a history of the unit’s previous occupants, mostly derived from reading their mail. He tells me about the electrical engineer who was fired after not showing up to work for two weeks, the antique collector who disappeared after selling a “sixteenth-century” armoire, the family of six that had, somehow, made do with the limited space.

“If you’re having second thoughts about me,” I say, “I understand.”

“No, no. No second thoughts,” he says. “I just want to make sure we’re clear on terms here. Do you take ice with your whiskey?”

He pours my whiskey neat and explains that he would introduce me to the documents if he didn’t have a pupil arriving soon.

“I get it,” he says. “I get that this isn’t what you do. I’m not asking that you find me all the special deductions, or that you find some way to stick it to big government in my name. What I want is to hand it over to you, and trust that whatever happens after that is legal. Maybe it’s not the perfect return, but I don’t have to worry afterwards about getting landed with a bad surprise or a knock on my door from federal agents. You hear me?”

“Heard,” I say.

He doesn’t name the sum that he’ll pay me out loud. He scribbles it on a piece of paper and slides it facedown across the table. When I pick it up, assess the number, and agree, he gathers two banker’s boxes from a closet in the hallway.

“I can’t let you take these home,” he says. “But you can work on them here in the evenings.”

The accounts are a mess. Records of all types are mixed in the same box—purchase and sale of gold items; an index of the students he tutored in guitar and piano, how many hours of lessons each had received, how many hours each had paid for; contracts for private performances at art galleries and houses; the booklet that tracked revenue from standard clubs and venues; a W2 from a department store at which he’d labored on piano during the holiday season, after which the management invited him to not return.

“I don’t take requests,” he says, when I ask him why.

I meet several of his students—Jorge teaches guitar and piano, privately, at a competitive rate—including a young man named Kyle, who does not look me in the eye when we shake hands but who I can feel watching me when I’m hunched over a stack of papers.

When there’s a question I’m uncertain about, I either call up an acquaintance who has some small knowledge of complicated documents, or I write the question down on a pad of paper and investigate available materials in our city’s libraries. Initially, I use the municipal branches before moving to one of the local college libraries, which is open later than eight at night and has a large legal collection. This library, however, is closed to the public, and it is only after long waiting periods that I can follow in behind someone with access. One student, an enterprising young man, notices my trespasses and offers, after pulling me aside in the reference section, to meet me outside the library at any time, for a small financial incentive.

“What do you use it for?” I say one time, as we’re walking up the stairs to the door. “The money I mean.”

“I play bridge,” he says. “And this will probably be the last semester I’m here because of it.”

“Bridge,” I say. “I’ve never played.”

“I’ll teach you some time,” he says, and disappears back into the night.

For simpler questions, I step outside, as if for a smoke, and use the payphone in Jorge’s lobby to call my acquaintance.

Various tenants walk through the lobby past the phone booth during my calls. We nod at each other, or don’t, make eye contact, or don’t, as they make their way to their rooms. During a phone call one evening, I hear the door open and close, footsteps on the thin carpet, and then nothing. It’s another minute or two before I realize that no one has walked past and that no other doors have opened. When I turn around, a tall woman is standing nearby.

“I couldn’t help overhearing your conversation,” says the tall woman when I exit the booth. “You’re a tax professional?

“An amateur professional,” I say.

She immigrated to our great nation from Turkey the year before, she explains, and is unfamiliar with the forms. She asks if I’m willing to take a look at her records.

“Of course,” I say, without hesitation.

She asks how much.

“We’ll worry about that later,” I say.

Her apartment is a clean, warm studio on the ground floor. There is no noise from the street or traffic, only occasional clanging as tenants throw their trash into the dumpsters outside. On the other side of the thin curtains and double-paned glass, wrought-iron bars secure the apartment against entry. She has no desk or dining table, so I look over the paperwork on a square coffee table made of a dark wood. The documents are simple—one employer, one W2, no assets, hidden or otherwise, no property, no marriage.

“And where do you work?” she says.

When I tell her, she says I must know everything about toilets. I tell her it’s a different kind of waste, and that I really only deal with the paperwork side of the department’s affairs.

She prepares tea, which I politely drink half of as I fill in the necessary numbers and perform the necessary calculations for ensuring that she will be, in the schema of one of our local intellectuals, not a good citizen, but a good inhabitant.

In the end, she asks if instead of paying cash, of which she has little, as I can see after filling out her forms, she could pay me instead in a coupon of sorts. She would give me a certain card that would identify me to a fleet of Turkish cabbies as an insider, a friend, part of the family. It would all depend on getting the right driver, but it could certainly save me time and money whenever I needed a cab.

“This is too much,” I say, looking over the card. “You let me know if any of your friends or family need my help.”

Over a breakfast of hard-boiled eggs, white noodles doused with a sweet peanut sauce, a warm broth of discrete ingredients, I tell one of the other tenants in my building about this. He confesses that he too is in need, that the small font on the forms gives him a headache, that he fears he is about to lose his job and lose everything.

“I sit down. I write out my name and date of birth, and then I lose it. I panic. I’ve thrown away six or seven copies of the same form with only my name and date of birth on them.”

“We’ll get past the date of birth,” I say, and drink my broth straight from the bowl.

My services spread by word of mouth, and soon I’m being approached several times a week by citizens who would never consider walking into a regular tax agency. Many of them are comforted that I’m willing to consider in-kind payment rather than pure monetary compensation. I earn dinner for two at an upscale Ethiopian restaurant; car repair work, which I accept on behalf of my brother’s troubled Datsun; an opportunity to either be hypnotized or have my fortune told, from a mystic; a moving van and crew, from a man who shared his name with a Roman general. In each case they put before me not only the documents but, unsolicited, the circumstances in which those documents were born—hidden pressures, petty conflicts, bizarre addictions and accidents. In each case they tell me what they can’t bear to tell their child, spouse, lover, business partner, colleague, priest, political representative, domestic servant, or, in one case, backgammon instructor.

As I continue laboring through Jorge’s trove, I become more and more disconcerted about the unexpected expenses emerging in the slough of documents, bills unpaid and forgotten, which I tally separately from the tax work. IOUs for strings and pedals from local music stores, phone bills—including a forty-five-minute, long-distance call to an unfamiliar area code—utilities, payment’s on the band’s dying van, tallies of pints drunk at a nearby bar, a note to pay, as quickly as possible, thirty-six dollars to “Char” for unspecified services, et cetera.

“There’s payments here totaling, approximately, two thousand and forty-six dollars,” I say one evening after his student leaves. “And that’s before what’s looking upwards of another thousand to the federal government.”

Jorge reads the list, asks for a pen, and crosses out the thirty-six dollars owed to “Char.”

“We got that figured out,” he says.

“That’s a start.”

But even after this conversation, it becomes clear that Jorge has not fully divulged either his assets or paperwork. It becomes clear that, either through negligence or dissembling, important details and documents have been kept hidden. A month in, I find a letter from his bank, detailing the year’s interest on his savings account, while searching the recycling for a note I threw away several days before. The reason I learn about the house he owns, located somewhere in the counties, isn’t because he thinks the information is pertinent to his legal obligations as a citizen to file taxes. It comes up when he relates an anecdote about provincial auctions.

“Two men walk in wearing top hats,” he begins.

2.

If everyone reacted to music as I do, nothing would ever induce men to fall in love.

—Stendhal

I leave once Jorge finishes his joke. The air that evening is cold enough, and my jacket thin enough, that I’m shivering within two blocks. My hope that the walk itself will warm me up collapses as the rainwater soaks through my shoes and into my socks. Madame Yu is sympathetic when I arrive just after she closes dinner, but she forbids me from using the stocks in the kitchen to prepare a meal, and explains that she would warm up leftovers herself if several friends were not arriving soon to play mahjong.

After switching my socks for a warm woolen pair, settling into a chair near the heater, and drinking a shot of whiskey, a great lassitude overcomes me, and I cannot bear the thought of venturing back into the cold, even for food. Half asleep, I’m visited by a specter, not one that deals in forms or bills or documents or money, but one who shuffles the same deck over and over, faster and faster until the cards bend at the middle and then, one by one, tear all the way through.

The phone rings shortly after midnight.

“You’ve seen everything there,” says Jorge, as I struggle to regain consciousness. “You know at this point that I don’t have the money to pay you what I told you I would, and you understand how embarrassing this is for me.”

“I know that,” I say.

He tells me that he’s been invited to play a local event at some sort of community center in celebration of Chinese New Year. He asks if I’m willing to accompany him on trumpet.

“I can drive you there and give you a hundred bucks for the performance,” he tells me. “To be straight up, that’s a fifth of what I’ll be paid. You know what I’m dealing with here. I can’t give you more than that. But you’ve got to get paid, too, and this will start that. ”

“That seems fair. It’s just the two of us?”

“Kyle will be there and he’ll get something, too,” he says. “Sandwich and soda money. Nothing he can get himself in trouble with.”

He explains further that we’ll be performing as a live band for the evening’s karaoke—approximately two hours at the end of the night.

“A hundred bucks is nothing to cough at,” I say. “But let me make you an offer. We’ll reduce my fee—how about by half—and instead of paying me that money, you’ll let yourself be hypnotized.”

“Hypnotized,” he says.

I explain the mystic’s payment plan, and that I have no interest in being hypnotized myself. “But perhaps I’d be more interested playing a different role,” I say. “Perhaps I could supply the orders to someone else who is willing to be mesmerized. Set the conditions.”

“I’ll have to think about it,” he says.

The next few weeks pass according to the established pattern—work at the office during the day, accounting for Jorge or other clients in the evenings. I practice trumpet in my apartment to prepare for our gig, first with various scales and then by playing along to old records. I take a break from accounting one Saturday night to visit an old jazz club, The Rattle, which receives a mention in Hong’s opus minimus as a place to which he could not return after an incident in which he “got tight and was visited by the ghost of a Negro singer with whom, in life, I had not been unacquainted.” There are no ghosts visible when I visit.

So much for Hong. I spend much of the day of our performance, a Saturday, at the library investigating a tax deduction for medical expenses incurred through government mandate (i.e., treatment for tuberculosis or other contagious diseases). The phone rings as I’m ironing a dress shirt.

“Tonight’s the night,” says Jorge. “Can you get a hold of your guy?”

“What guy?” I say, laying the right sleeve flat on the ironing board.

“Your hypnotist. I want it to be tonight, before the show.”

I stand the iron upright, then say “We have to be careful here. This is a big event tonight, and there’s money on the line.”

He insists.

Over the glare of the headlights, I see Kyle crawl from the front seat into the back when they arrive in the van to pick me up. Jorge drives without changing the radio station, even for the worst jingles. He talks only to ask for the mystic’s precise address. The route he takes is curious and circuitous, rarely following the same street for more than a few blocks, keeping to residential side roads lined with burnt-out streetlights, dilapidated garages, and tall, bent trees with naked limbs.

The mystic’s house—rented to the mystic after the previous tenants were discovered to be “subletting” rooms at an hourly rate—is marked by a large sign out front advertising fortune-telling, hypnotherapy, and hydrotherapy.

“Wait in the car and watch the instruments,” Jorge says to Kyle. “We’ll be back soon.”

Kyle says something, but it’s lost as we slam the car doors.

The mystic’s sanctuary is accessed by way of a long hallway lined with curtained doorways. A radio announcer’s voice gets louder and then softer as we approach and continue on past one of the rooms. Claws of some animal, I presume a dog, click on a hard floor nearby, but the creature does not appear.

“Watch your heads,” says the mystic, and we all duck through a short opening into the sanctuary.

“So you’re a hypnotist,” says Jorge when we’re all sitting around the table. “You must have seen some strange times.”

“There was once,” says the mystic, “what I would refer to as a fecal event. I lost three of my rugs that day and haven’t yet replaced them. You lose some atmosphere, but hardwood is a hell of a lot easier to clean. I would call that a strange time.”

The wall behind him is pocked with niches holding statuettes of elephants and six-armed goddesses, colored beads and scraps of cloth, a curved knife that seems more ceremonial than functional, icons of saints, glass bottles, and what looks like vellum written over in Arabic.

“I can light some candles and incense if you want,” he says. “But it really doesn’t matter.”

“Let’s do a candle,” I say. “Right here in the middle of the table. I’m not too big to say I don’t need it.”

He walks into the other room, a stovetop burner clicks and ignites, and he returns with smoke swirling against his chest from two incense sticks and a votive candle. He positions these at the center of the table and removes a brass bowl from a niche in the wall behind him. He raises this on the fingers of one hand, raps the side with a short rod, waits until the reverberations have died out, and hits it again. This carries on for some time.

The mystic leans across the table and whispers into Jorge’s ear before saying, for all of us to hear, “Alex has something to tell you.”

Jorge nods and looks at me.

“And what do you want to tell him,” the mystic asks.

The question takes me by surprise. The short notice for this session and the preparations for the evening’s events had left me with little time to consider what I would say to Jorge while he was in his hypnotic trance.

“There’s a man following you tonight,” I say, after a moment. “A Chinese man who knows you trade in gold. If he hears you play a song, any song, and if you play that song, any song, without making any mistakes, he’ll gut you with a serrated knife.”

The three of us consider this. The mystic repeats, “A Chinese man is following you tonight. He knows you trade in gold. He thinks you’re loaded. He’ll follow you to the party. If you play a single song without making an error while playing, he’ll disembowel you on stage with a serrated knife.”

The mystic balances the bowl on his thumb and two fingers, and hits it a final time.

“That’s it?” says Jorge.

“That’s it,” says the mystic.

“That’s that,” I say. “We’ll be late if we don’t leave soon.”

Kyle is shivering when we step back in the car. He holds his hands between the front seats toward the air as it circulates, first cold and then warm, through the vents.

The building is pale brick, two stories tall, set back from the street by a large plaza of the same pale brick with a fountain in the center. Statues of simian creatures with gaping maws, knobbed joints, and ridged spines guard the door on either side. Children run around carrying blazing sticks, setting light to fireworks. One boy, as we walk by, pulls off a girl’s thick gloves so she can operate her lighter.

“What did he tell you?” I say to Jorge as we near the entrance. “The mystic, I mean.”

Jorge shakes his head.

The interior looks as if it were modeled after an old train station, a large open room interrupted with black marble columns and lined with tall, paned windows that, during the day, would have allowed for most of the interior to be lit naturally. A staircase at the far end of the room leads up to a mezzanine. Large woodblock prints decorate the walls, depicting naval battles, scenes from country life, an octopus pleasuring a woman. Although the room is altered, and in full color, I recognize it from a photo in Hong’s book.

“The owner, Mr. Li,” he writes, “Was known for sending his agents to China to find promising but impoverished youths. He paid for their passage to our great nation, where they would be trained as pool hustlers and kept under his employ until they had earned so many dollars.”

The night is well under way at this point, hundreds of celebrants moving between the many card tables, stopping sometimes to watch the next hand played out, yelling out advice on strategy and warnings about other players, placing bets with whoever will take them. They crowd tightly around the mahjong tables, ferrying drinks to the old women who likely have not stood up in hours. The billiard players are mostly young men, black hair slicked back. Cash changes hands quickly and openly, both American dollars and Chinese currency, which Kyle tells us is called yuan.

As we’re walking through the middle of the hall with our gear, the host presents not only himself but also a bottle of Chinese whiskey labeled in green with gold script.

“Later, you may drink this,” he says, grinning, and motions us to follow him up to the mezzanine. The crowd parts, perhaps because they see the gear we’re carrying, perhaps because they see our guide.

A wide staircase leads up to the mezzanine, where the stage is located. Halfway up, the stairway splits, and a statue of a two-faced figure points to both sides. The rat face points to the left; the monkey face, to the right.

The first singer is a middle-aged man in a red turtleneck, hair parted on the side of his head, glass of whiskey in the right hand, microphone in the left hand. He picks a slow ballad filled with multiple, extended instrumental breaks—possibly the worst species of song for karaoke. I wait until the end of the first chorus to jump in, playing a brief line that exactly matches the melody of the verse—a safe move for an unfamiliar song.

It happens then, and it surprises me, even knowing what was said at the mystic’s. Jorge leads the first measure of the second verse with the wrong chord, a full step off in our key. Kyle fumbles on his guitar as he tries first to match the error and, second, to return to the proper progression. The man in the red turtleneck remains oblivious. He stands on his tiptoes, arches his back, and belts out the chorus. The crowd cheers him back to his seat as the host calls up two young women for a duet.

I establish a pattern of performance, as we cycle through singers and songs. A few bars on the intro and outro, fills between full measures, a solo after the final chorus. I take up the melody when the singer falters or loses his place and sings the chorus over the verse’s chords.

Jorge introduces a single error into each song, and with each error Kyle becomes more unnerved, turns paler and paler in the yellow glare of the spotlights. Between two songs he wipes sweat from his forehead, drinks a tall glass of water, and stares at the strings on his guitar.

“One hundred and fifty years ago” says a reporter when he writes up this performance months later, at the opening of his piece on Jorge, “A man wrote of the Chinese that ‘It would seem as though history had first to make this whole people drunk before it could rouse them of their hereditary stupidity.’ And it did seem that the drunk, against the sober, were the more clever at betting, the more confident at singing, the more coordinated at dancing. They called every bluff and hit every falsetto note.”

About halfway through the evening I notice the man sitting alone at one of the large circle tables. He wears a gold watch, horn-rimmed glasses, and a short mustache. While everyone watches the singer dancing across the stage, he keeps his eyes on us, even as a server brings him a pork steak.

The song finishes. A woman wearing blocky, buckled shoes takes the microphone and rolls up the sleeves on her sweater. Kyle is bothered enough that it doesn’t take an error from Jorge for him to start the song in the wrong key. I close my eyes to concentrate on doing what I can to salvage the intro. When I open them, I see the man at the round table saw through the pork bone with a serrated knife, stick his tongue in the center, lick out the marrow. When he cuts through the bone again, bits of dark brown sauce spray onto his white shirt and the tablecloth from the force of his sawing. The table shakes and, as it does, I lose track of the key, the tempo—the song altogether—and play the same major scale over and over. Kyle looks straight at me, mouth wide open.

At the end of the night, the host hands Jorge an envelope, which Jorge puts in the inside pocket of his jacket without opening.

“Mr. Li was very pleased with your performance,” the man says.

“We didn’t know he was here,” says Jorge.

They shake hands and offer each other good fortune in the coming year.

It’s only after we’re in the car that Jorge opens the envelope and pulls out not green bills but four red Hong Kong hundred-dollar bills.

“Maybe with the exchange rate this will actually be a windfall for us,” I say, but Jorge crumples the bills and tears the envelope into smaller and smaller bits, which flutter to the floor of the car.

When I arrive at my apartment building just before dawn and walk past Madame Yu’s unit, the door, as usual, is open. Although I don’t make it to breakfast, the other tenants let me know that, when they went to eat, there wasn’t so much as a fried egg prepared.

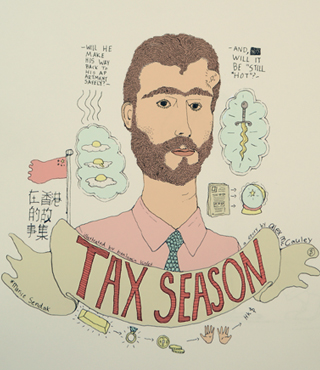

Editor’s note: the sketch for this article was done by Benjamin Violet. You can learn more about the artist at @fakebenjamin.

1. This memoir, somehow, was both self-published and published posthumously.