But certainly for the present age, which prefers the sign to the thing signified, the copy to the original, representation to reality, the appearance to the essence . . . illusion only is sacred, truth profane. Nay, sacredness is held to be enhanced in proportion as truth decreases and illusion increases, so that the highest degree of illusion comes to be the highest degree of sacredness.

—Ludwig Feuerbach, The Essence of Christianity

When a patient first seeks help from a psychotherapist for issues of depression and anxiety, the therapist often discovers that those symptoms signify an identity crisis, a separation between the patient’s projected sense of self and their material actuality. The depression and anxiety are visible symptoms that reveal a deeper unraveling of the patient’s psychological safety nets, an unraveling that threatens the patient’s professional opportunities, moral convictions, and martial aspirations. Likewise, when we look around the world and see the protests in Greece, the Arab Spring movement, and, more locally, the Occupy Wall Street movement, it seems likely that these instances of political unrest are the outward manifestations of a much deeper and more systemic problem.1 It seems likely that the current political unrest is a symptom that points to alienation from ourselves and from one another in and through the spectacle of capitalism.

Religious sects squabble relentlessly over their dogmatic theologies, but this idea of alienation, of separation, is one of the more common and least controversial starting places for talking about sin. For instance, Isaiah 59:2 states that “Your iniquities have made a separation between you and your God, and your sins have hidden his face from you so that he does not hear” (ESV). Adam and Eve were also separated from God after their first sin by being exiled from the garden in which God’s presence resided “among the trees of the garden” (Gen. 3:8). Even Paul Tillich, one of the most influential theologians of the twentieth century writes that “Sin is separation. To be in the state of sin is to be in the state of separation. . . . We not only suffer with all other creatures because of the self-destructive consequences of our separation, but also know why we suffer. We know that we are estranged from something to which we really belong, and with which we should be united.”2

Separation is also a common theme in the Marxist tradition. Karl Marx himself argued that “Estranged labor turns . . . man’s species being, both nature and his spiritual species property, into a being alien to him, into a means to his individual existence. It estranges from man his own body, as well as external nature and his spiritual essence, his human being.”3 Labor separates man from what it means to be human, what it means to be an integral part of the human species. Labor both produces commodities and objectifies workers on the basis of their economic output. They are no longer seen as human but are instead viewed as machines; they are commodities that produce other commodities, which is why workers have been all but replaced by machines in the advent of the technological revolution. The Internet has replaced local bookstores, and supermarkets have replaced cashiers with self-checkout machines—the logic of labor sees human beings as worthless, only assigning worth to their output and to the accumulation of profit.

Although some might assume that the transition from manual labor to cognitive labor has been a blessing that frees humanity from slave-like work, Franco “Bifo” Berardi updates Marx’s critique of industrial capitalism to the twenty-first century’s semiocapitalism by arguing the opposite. Cognitive labor has stolen the eight-hour workday by providing an endless line of instant communication outside our paid hours of work. As Berardi states, “The entire lived day becomes subject to a semiotic activation which becomes directly productive only when necessary. But what emotional, psychological, and existential price does the constant stress of our permanent cognitive electrocution imply?”4 Smart phones allow us to check our e-mail twenty-four hours a day, laptops can be slipped into our vacation carry-ons—instant communication has oriented our entire day, even our days off, toward work.

The workers may have freed their bodies from manual labor, but they put their very souls to work through cognitive labor. As Berardi suggests, “Industrial factories used the body, forcing it to leave the soul outside the assembly line, so that the worker looked like a soulless body. The immaterial factory asks instead to place our very souls at its disposal: intelligence, sensibility, creativity and language.”5 The logic of labor constrains the human soul to its output. Thus, many people come home from work too exhausted to do anything life-giving, and they turn on the television, video games, or computer to virtually role-play, vicariously living someone else’s life because their soul is too taxed to live their own.

Despite never truly being free from work’s objectification, the hegemonic view within the United States commonly links free-market capitalism to democracy and freedom; the American dream has always been a synonym for the belief that if we work hard enough we can pull ourselves up by our bootstraps.6 These pseudotruths provide the psychological safety net that validates our alienation. According to Guy Debord, these psychological safety nets are the spectacle separating the material actuality of capitalism and “an uninterrupted monologue of self-praise” used to validate its actions and self-image.7 There is a disparity between the mythological ideas capitalism promotes about itself and the way the capitalist reality manifests. This separation is most clearly shown by macroeconomic data, which show that the rich keep getting richer while the poor keep getting poorer.8

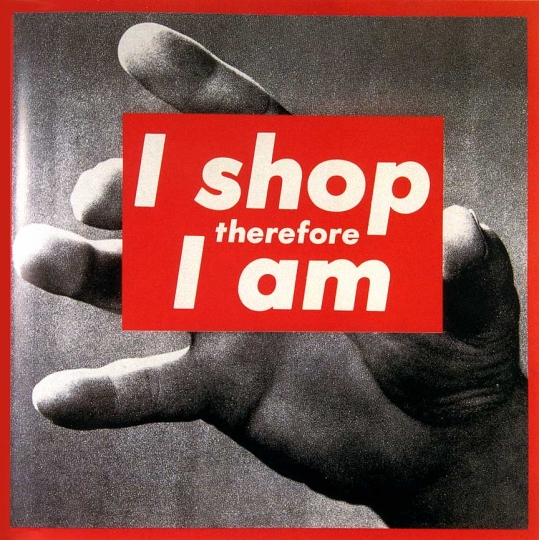

The spectacle is a worldview promoted by a confluence of capitalism, mass media, and governments that has been actualized into the material realm; it refers to the commodity’s colonization of social life because it takes all that once was directly lived and turns it into mere representation by supplanting relations between people with relations of commodities.9 As Debord puts it, “The spectacle is capital accumulated to the point where it becomes image.”10 Consumerism creates a culture that makes us feel as if we need a fancy car or a big house to create an image of wealth that will impress our friends or strangers. It is, however, important to note here that Debord does not mean that the advertisements themselves are the spectacle; rather, the spectacle is the way in which the projected image mediates people’s interactions,11 and the way the spectacle mediates people’s interactions is through separation, as Debord states: “Separation is the alpha and omega of the spectacle.”12 The spectacle separates us from others by changing our interactions with others based on the judgments we make of their appearance and whether or not that fits into the culture industry’s definition of cool. We no longer see people with curiosity for who they really are, but instead we place them into the stereotypical images provided by the spectacle.

The spectacle also separates us from ourselves because we come to understand that to be accepted by our peers we have to live into the images that culture defines. Every subculture has certain images of how to act and look, and all of theses images correspond to products to buy. Certainly a choice exists as to which subculture we choose to fit ourselves into, but the choices are limited to what the spectacle presents as viable options. And the more we live into, idolize, and believe the images of need proposed by the dominant culture industry, the more we become alienated from ourselves. By adopting the image of the spectacle, our actions are no longer our own. Our actions become those of people outside ourselves who represent our actions for us.13 Thus, just as estranged labor controls our actions and activities while on the clock, the more we define our desires by the desires proposed to us in advertisements, the less control we have over our lives while off the clock.

This spectacular separation is evident in our everyday lives. Raoul Vaneigem argues in The Revolution of Everyday Life that there is a difference between living and surviving. He defines survival as “life reduced to economic imperatives. Therefore, survival is life reduced to what can be consumed.”14 Obviously this applies to the 40 percent of the world who live on less than two American dollars a day, those individuals who are barely surviving. Yet this characterization also applies to the rest of our society, as consumerism separates us from authentically living our own lives. If we are constantly idolizing the things we buy to the point of constructing our self-identity in terms defined by the brands we wear, are we truly living life as ourselves? Or are we just surviving inside images that someone else created for us? If we live into this manufactured image of who we are not, it will not be long before we forget who we are.

Outside of living into the stereotypical semblance the spectacle has created for us, there is an anxiety caused by our desire to be loved and accepted by others. We numb our true desires and concentrate on keeping up the necessary image so that we may be accepted by the rest of society. As Vaneigem states,

Survival is life in slow motion. How much energy it takes to remain on the level of appearances! The media gives wide currency to a whole personal hygiene of survival: avoid strong emotions, watch your blood pressure, eat less, drink in moderation only, survive in good health so that you can continue playing your role. . . . Today our respect for life prohibits us from touching it, reviving it or snapping it out of its lethargy. We die of inertia.”15

In order to function within society, we must be confined within its restraints. Yet the restraints of society’s spectacle separate us from truly living life as ourselves, because our anxiety for acceptance numbs our true desires in order to stay within the comfort of society. Imagine, for instance, if time were literally money: the rich could only die of bodily harm, and thus they would never truly live because they would be afraid of taking risks; they would only seek out a safe, numb, and comfortable survival.

Yet how do we bridge this gap between living and surviving? How do we end the separation within our selves and start living authentically? Vaneigem argues that we can only traverse this gap through love and the revolution of everyday life: “People who talk about revolution and class struggle without referring explicitly to everyday life, without understanding what is subversive about love and what is positive in the refusal of constraints—such people have a corpse in their mouth.”16

Love is an anecdote to alienation because it connects. Love not only connects people to one another, but it also roots people within themselves. If we truly love ourselves, we will not be afraid to show who we are to the world instead of embracing the idolized, manufactured identity the spectacle imagines for us. By embracing our own bodies, spiritual essences, and what it means to be our authentic self as defined outside of the spectacle, love for the self allows us to live as our true selves. And then we can turn this love of self toward the other, applying the same love of self to the other. We must have a love and awe for the other that helps us treat the other as a person and not as an object through which we can gain something. We must love the other as the other loves his or her self, so as to ensure that the other’s personal needs and countertransference do not overshadow or objectify him or her.

If only we actually followed Jesus in what he identified as the greatest of all the commandments—love God and love people—then every Christian would be a revolutionary in their everyday life. The world we live in faces many problems—economic, social, political, and environmental—yet the capitalistic narrative continues with life as usual. These problems are the outward manifestations of our sin and of the separation caused by spectacular capitalism. We are separated not only from the means of production, in that we don’t know where our products come from, but also from our selves and others. Ending this separation would be truly revolutionary for it would reorient our interactions with the world around us. Through the love of self and love of others, we can become revolutionaries as we reorientate our everyday lives outside the spectacle. Love reunites us with others, for it helps us see them with a curiosity for who they really are rather than according to qualities that are defined by the spectacle. Love changes how we fulfill our basic needs because it means that we actually care about how they are fulfilled—if we really love others as Jesus would have us love, would we still buy T-shirts, shoes, chocolate, and other products from corporations that oppress their workers? Love is the antithesis to sin and central to human being, as we long to love and to be loved, to be connected rather than separated. Love bridges the gap between living and surviving because it reawakens our heart to beat, to care, and to live authentically outside the prescriptions of the spectacle.

1. Gustavo Beck expands upon this idea of the relationship between psychology and politics in “The Psychic Economy of Occupy,” Adbusters America, November 1, 2012, 19.

2. Tillich, The Shaking of the Foundations (New York, NY: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1976), 154–55.

3. Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, ed. Dirk Jan. Struik, trans. Martin Milligan (New York, NY: International Publishers, 1993), 114. Emphasis in the original.

4. Berardi, The Soul at Work: From Alienation to Autonomy (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2009), 90.

5. Ibid., 192.

6. An ironic metaphor considering physics has proven that it is nigh impossible for a person to actually achieve such a task.

7. Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York, NY: Zone Books, 1994), 19.

8. United Nations Development Programme, “Summary,” Human Development Report 2005, 17–18.

9. Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, 12, 13, and 29.

10. Ibid., 24

11. Ibid., 12.

12. Ibid., 20.

13. Ibid., 23.

14. Vaneigem, The Revolution of Everyday Life, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Seattle, WA: Left Bank Books, 1983), 159.

15. Ibid., 161.

16. Ibid., 26.