In antebellum America, at the height of national debate over the worth of black bodies and the proper sphere of female bodies, Julia A. J. Foote burst into the public arena preaching a new doctrine of sanctification. An African American freedwoman, Foote proclaimed that God offered salvation to the entire person here and now. Her vision of God resoundingly denounced the reigning theology which promised immediate justification through conversion but declared that sanctification was postponed until heaven. Against this error, one she linked with racial and gender segregation, Foote’s gospel message offers a richly embodied theology that makes way for all people to experience God’s offer of full salvation. Even today, Foote provides a pattern for confession of the errors of segregation within the church and society, for encounters with the fullness of Christ’s gospel, and for hope in God’s abiding promise to save on God’s own terms.

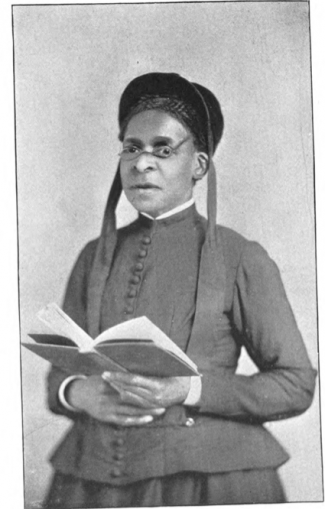

Julia A. J. Foote lived to defy classifications given to her from family, the church, and American society. Born in Schenectady, New York, in 1823 to parents who had recently purchased themselves out of slavery, Foote grew up as a free black with little formal education. She was hired out as a servant when a young girl, and she married at eighteen. Despite discouragements from her parents and her husband, Foote sought out holiness doctrines, was converted, and began to preach entire sanctification among her acquaintances. Undeterred by detractors and the threat of excommunication from the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) church, Foote carried out an itinerant preaching ministry throughout New England, Maryland, and Ohio from the 1840s through the 1870s. Though she acted without ecclesial approval for the majority of her career, the AMEZ church eventually ordained her as a deacon and then elder shortly before her death in 1900.1

In A Brand Plucked from the Fire, Foote defended her gospel, her black body, and her female gender with deftly intertwined body imagery, Scripture interpretation, and theological discourse. Like other African American female autobiographies of the time period, Foote’s memoir affirmed her own self-worth, demonstrated self-determination, and established herself as a voice for her people.2 Markedly absent from her narration, however, are specific dates for national events. By the publication of her memoir in 1879, Foote’s public ministry spanned the antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction periods of American history, but she mentions none of them. As a result, Foote’s narration exposed antebellum Northern prejudice, Southern slaveholding, and the Reconstruction era beginnings of Jim Crow social legislation as one continuous, oppressive corruption of all American bodies.3 The segregationist treatment she and other African Americans received in the North before the Civil War served, therefore, as both a history of how things were as well as a vivid portrait of continued oppression in her present day.

Not one to speak gently, Foote begins her narrative with a drastic account of the habitual dose of Sunday morning discrimination her parents imbibed at church. Instead of welcoming her parents and other blacks as “Christian believers,” the church balconied and cornered them off like “poor lepers,” forbidden to approach the Eucharist table until all whites had been served. One morning, her mother and another woman accidentally left the balcony to receive Eucharist just as two white members belatedly rose to approach the table. The women were stopped by a “mother in Israel” who

caught hold of my mother’s dress and said to her, “Don’t you know better than to go to the table when white folks are there?” Ah! She did know better than to do such a thing purposely. This was one of the fruits of slavery. Although professing to love the same God, members of the same church, and expecting the same heaven at last, they could not partake of the Lord’s Supper until the lowest of the whites had been served.4

In the story, Foote’s use of scriptural imagery exposes the most pious church matriarch to be a blind spiritual guide, “deluded by a spirit of error.”5 By enforcing segregation between white and black bodies, this church matriarch considered herself an earnest protector over the purity of the Lord’s table. With parabolic wit that plays “fruits of slavery” as foil to the equalizing and unifying truth of “same God, same church and same heaven,” Foote overturns this claim of righteous behavior. The mother in Israel was now none other than a blind guide, leading Foote’s mother into the error of segregation through the Christian sacrament.

Although her parents had been led into error, Foote severely critiques their feeble faith as a way of unmasking the tyranny of segregation within the corporate church. The nadir moment in the Eucharist scene is not the matriarch’s control of the table but Foote’s description of her mother as a Christian who “did know better than to do such a thing purposely.” Both the matriarch and the freedwoman, in Foote’s view, are blinded by a segregation that would limit God’s salvific reach on earth, and both women are responsible for their own blindness. By accepting her place in the balcony and behind whites, this newly Christian freedwoman continued to embody the theological claim that privileged white over black and male over female in God’s economy of redemption—no matter how often the preacher declared God’s salvation was offered to all.

Foote’s unflinching critique of her parents also foreshadows her critique of all the African American churches that continued to accept a segregation between faith and full salvation, between black and white, and between male and female. According to Foote, for Christians to believe and act as if black bodies and female bodies must be lower than white bodies and male bodies, is to know “little of the power of Christ to save.” For Foote, love of the same God, membership in the same church, and expectation of the same heaven should result in a negation of any segregationist impulse within Christian doctrine or ecclesial practice. However, Foote believed that the current theology “that all Christians had . . . inward troubles to contend with, and were never free from them until death” resulted in feeble faith and permitted racial and gender segregation within the church.6 Her gospel of “full salvation,” or entire sanctification, speaks of healing the church from this separation and division, as sanctification is assured through a second conversion by the power of the Holy Spirit.

Foote uses her own conversion experience as a witness to the far-reaching effects of sanctification upon the whole person. She explains her own experiences before receiving entire sanctification as “living in an up-and-down way.” Though Foote believes her first conversion brings justification, she is still troubled by the “struggling and fighting of this inbeing monster” of anger and pride. She also experiences external disappointments, as pro-slavery prejudice repeatedly thwarts her desire to receive an education so that she can read Scripture.7 External disappointment led to internal struggle, and vice versa; inextricably linked, both struck her as evidence of the continued power of sin in her life.

Almost overcome by the struggle, Foote finally finds peace in the gift of entire sanctification. In seeking resolution through the Holy Spirit, she feels the gift of God’s “full salvation” dispel the nagging doubts and the power of sin. Foote believes that neither sin nor the power of sin exists within the sanctified Christian, and no external error or persecution can dislodge the power of the Spirit within. To Foote, the tempests of the world may rise and howl, but the sanctified Christian remains a child of God and stands immovable, like an “iron pillar or a house built upon a rock.” 8

Empowered in body and spirit by such “full salvation,” Foote’s embodied gospel of sanctification stops short of confusing humanity with God. Foote protests, “I am not teaching absolute perfection, for that belongs to God alone, but Christian perfection—an extinction of every temper contrary to love.” Foote explains that entirely sanctified Christians can err or misunderstand and need to continually rely upon God. In return, God continues to bestow gifts of illumination of the mind, purification of the heart, and filling of the soul with the love of God, “bringing forth fruit to his glory.”9 These gifts empower all of the Christian’s being to live for God.

Once an unworthy nobody, Foote now believes she is “somebody” in the eyes of God.10 Foote’s own experience of entire sanctification provided her with the power to resist any teaching or social restriction that treated her as less than a fully saved child of God. Believing in the gospel of entire sanctification, Foote was free to stand as her whole self before God and to love God with body, mind, heart, and soul. She had studied Scripture and experienced God’s grace, and she found that God desired to save her whole self and would accept nothing less. Because she was wholly made new and free from sin, to live as if any aspect of her body was excluded would be to live against the doctrine of entire sanctification and to succumb to the worldly error of segregation.11 And Foote believed that any minister or congregation who followed such erroneous logic had no authority to dictate the parameters of her body, her salvation, and her calling from God.

Foote’s interpretation of her call to preach also supports her understanding of God’s desire to sanctify her body as well as her soul. Foote admits that she did not initially accept God’s call to preach because the idea that God would call an uneducated, black female caused her great doubt and fear.12 When Foote finally agreed to preach, she received a vision where the Three Persons of God prepare her to preach as they attend to her body. In the dream, God the Father took Foote by the hand and led her to silver waters before giving her hand to Christ. God the Son then baptized Foote, stripping off her old clothes and washing her in “water feeling quite warm.” After Christ walked her to the shore, the Father clothed Foote in new robes. She then followed the Trinity and a company of angels to a tree, where God the Holy Spirit plucked fruits and fed them to Foote. After eating, the Father declared her prepared to “go where I have commanded you.” When Foote expressed doubt of being believed, Christ provided her with a golden letter of authority to place in her breast. Upon waking from her vision, Foote discovers the scroll is within her heart, to be shown in her life.13 Foote interprets God’s attentive cleansing and feeding in her vision as a sign of God’s acceptance of her female and black body in sanctification, as well as a truth that she must witness to in her preaching of entire sanctification.

Bolstered by such vivid scenes of God’s call and care for her body and soul, Foote refused to order her life or her ministry by a logic of racial or gender segregation, which she labels “error.” For example, after her minister excommunicated Foote for holding meetings on sanctification, Foote appealed the excommunication with a personal petition to the larger AMEZ denominational body, telling them, “I considered myself a member of the Conference, and should do so until they said I was not.”14 Or when another minister attempted to rescind an offer to preach at his church as a way of keeping the peace among his parishioners, she refuted his position by explaining that “if I am invited . . . to use the weapons God has given me, I must use them to his glory.”15 While on a preaching tour “laboring for white and colored people” through Ohio, Foote would not preach to any white congregation that would not open “their house” to admit African Americans.16 In each of these examples, Foote held her authority from God, given to her through the gospel of entire sanctification, above the authority of anyone who would require her to conform to erroneous social logics that would segregate justification from sanctification, female from pulpit, and white from black. Aware of the reproach she incurred and the trouble she stirred, Foote continued on, believing she fulfilled her “commission from heaven” and relied on “Christ alone.”17

With stony determination, Foote announced the need for structural change within the church along with the tenets of entire sanctification. Just as Foote refused to abide by segregation in her own life, she also urged the corporate church body to refuse segregation as well. Though her sermons about sanctification began with a focus on the inward soul and personal salvation, she seamlessly tied these lessons to curses at “Prejudice,” encouragements for other Christian sisters, and warnings against “worldly” honors, pleasures, designs, and pursuits.[18] As she wove the personal and social together, Foote tied sanctification closely to the immediacy of heaven, or the in-breaking reign of God. For example, in her exhortation to Christian sisters, she reminds them that one day they will all “unite with the heavenly host in the grand chorus,” and therefore, they should not silence themselves for fear of worldly reproach.19 By directly contrasting the noisy heavenly host with the censorship of human opinion, Foote pressed the church to move away from “the fruits of slavery” and gender discrimination and toward the same God and the same heaven at last.

Foote also deliberately took action to promote herself as a preacher of the gospel, believing that she and others like her witnessed to the power and truth of entire sanctification. When she attended the AMEZ Conference to appeal her excommunication, Foote met women who also “believed they were called to public labors in their Master’s vineyard” but were so distressed by opposition from ministers that they “shrank from their duty.” Foote gathered the women together and proposed a series of revival meetings “under the sole charge of women.” The women rented out a building and held nightly meetings of singing and preaching. Foote reported that the meetings were “a time of refreshing from the presence of the Lord,” attested by many conversions and sanctifications. Foote’s cohort even closed the meetings with a love feast, which caused a great “stir” among ministers and church members.20 Though her critics gossiped that Foote was withdrawing to form a new denomination or spiritual cult, Foote held her ground as a committed member of tradition. With a defiant embrace of gospel preaching through bodies just like hers, her encouragement of sanctified preaching continued to press for the reorganization of the church body toward equality between men and women.

As candidly as Foote described herself entirely sanctified by God, she also narrated her failures at preaching the gospel and refuting the error of segregation. Foote won the debate against the minister who appealed to peace, but in the end he succeeded by placing himself in the pulpit and refusing to move. Her attempts to defy racism and prejudice while traveling from city to city produced mixed results.21 Foote also experienced a crisis of doubt for several years while suffering from a vocal illness and the death of her husband, but she was eventually restored to faith and later her ability to preach. 22 Foote believed experiences of oppression and her own bodily weaknesses did not exclude her from anointed service. On the contrary, they intensified her witness to God’s judgment against the errors of segregation and God’s superior activity of full salvation. Despite the difficulties, she continued to believe in God’s immediacy and loving concern for every aspect of human life, including our bodies.

Through her life story, her teaching, and her preaching activities, Julia Foote’s theology of sanctification offers a pattern for maintaining an awareness of human bodies in our theological reflection. First, Foote’s denunciation of segregationist theology and Christian practices of communion exposes the discrimination hiding beneath social propriety, theological orthodoxy, and liturgical orthopraxy. Just as Foote minimized historical markers so that antebellum Northern prejudice slid neatly into post-Reconstruction segregation for her readers, her memoir continues to slide forward, pressing current readers to confess the “error of segregation” in their own place and time. Foote’s refusal to separate her body and spirit underneath the cleansing power of God continues to sound a forthright, unequivocal refutation of what Emilie Townes calls the “fantastic hegemonic imagination” of racial and gender segregation. Townes similarly identifies the “rending of the marvelously complex interlocking character of our humanity” as “the most devastating impact of the cultural production of evil” still found within theological and cultural worldviews. This rending “encourage[s] us to separate our bodies from our spirits, our minds from our hearts, our belief from our action.” Both Townes and Foote agree that the way past the hegemonic imagination is to begin by admitting that it is a force “deep within us,” one that everyone must “answer [for,] remembering that we are in a world that we have helped to make.”23 Foote’s candid critique of her own African American denomination alongside her unyielding refusal to legitimate any form of prejudice by white churches and white American society, therefore, provides a pattern of confession that all have fallen short and that all are bound by the hegemonic “error of segregation.”

Foote’s courage to confess was followed by her stony determination to proclaim the sanctifying power of an encounter with God. As her message embraces her body and attends to the bodies of others, Foote’s doctrine of sanctification provides a vision of God’s saving grace upon whole persons and whole communities. Much like M. Shawn Copeland describes the character of Baby Suggs from Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Julia Foote was a historical voice of hope toward “the principle of life, which is love, and call[ed] the freed people to new identity-in-community, to the demands of proper love of the black self, black body, and black flesh.”24 Yet Foote went further still and called both white and black into proper love of self, body, and others through sanctification. In Foote’s belief in God’s love for her own body, in her encouragement of other African American women, and in her stubborn refusal to bend to prejudice, Foote witnessed to the freeing power of God to African Americans. And despite the segregationist evidence against them, Foote believed that God’s promise of sanctification extended to white bodies and souls too. Yet with her visions of being washed by God and the same heaven at last, Foote continues to overturn the segregationist hierarchies, reorganizing everyone within the church according to the heavenly table. To encounter the fullness of Christ’s gospel, whites could not maintain their closed congregations or their place at the head of the communion line.

Foote’s gospel of entire sanctification was ultimately a statement of hope in the continued generosity of God’s promises over the whole person and the whole of the church community. No matter what the church matriarch or powers that be said or did to organize God’s family or God’s table according to the errors and hegemonies of segregation, Foote continued to proclaim, “Yes, yes; our God is marching on.”25 Two hundred years later, Emilie Townes presses the church to witness to this very same God, who is “justice wrapped in a love that will not let us go and a peace that is simply too ornery to give up on us.”26 Perhaps Foote’s tenacious moxie wasn’t merely a personality trait after all. Her persistence was also the embodiment of an ornery God who persists in saving on God’s own terms and sometimes in spite of the blindnesses within the church and Christian theology.

Although the doctrine of entire sanctification had its heyday in the nineteenth century, Julia Foote remains a powerful example of embodied theology.27 Her theology of sanctification is complex and multilayered because she sought to live as an entirely sanctified person. Through autobiographical story, Foote exposed the deformative influences of racial and gender segregation that she and other black women experienced in theological teachings and Christian worship practices. In her theology of sanctification, she attends to God’s redeeming power upon the whole person, body, and soul. In doing so, Foote refused to bend to the errors of segregation, and worked for gender equality in the pulpit and racial equality in the congregation. At the heart of these activities was her eschatological vision of unity, a vision of “the same God and the same heaven at last” in the church, experienced here and now through entire sanctification.

As we wrestle with the relationship of theology and the body in our current contexts, Foote provides a pattern for maintaining an awareness of human bodies and social logics of the body in our theological reflection. As an embodied message of salvation, her theology of sanctification provides a pattern for confessing the continued influence of segregation, for encountering the full grace of Christ to root out these errors, and for witnessing to hope in God’s promise of justice and redemption.

1. William L. Andrews, ed., introduction to Sisters of the Spirit: Three Black Women’s Autobiographies of the Nineteenth Century (Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press, 1986), 9–10.

2. Elements in Julia Foote’s narration parallel Clarice J. Martin’s summary of African American autobiographical elements in “Biblical Theodicy and Black Women’s Spiritual Autobiography: ‘The Miry Bog, the Desolate Pit, a New Song in My Mouth,’” in A Troubling in My Soul: Womanist Perspectives on Evil and Suffering, ed. Emilie M. Townes (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1993), 15–21.

3. According to Emilie Townes, Jim Crow legislation in the South was created with the help of northern antebellum segregation as model: “By 1860, nearly every phase of Black life in the North was segregated from Whites. Railroad cars, stagecoaches, and steamboats all had special Jim Crow sections designated for Blacks alone. This segregation extended to theaters, lecture halls, hotels, restaurants, and resorts, to the schools, prisons, hospitals, and cemeteries. In White churches, Blacks sat in ‘Negro pews’ or in ‘nigger heaven’ and had to wait to receive communion after the Whites. . . . Northerners contented themselves with a virtually slave-free society. However the presumptions and stereotypes undergirding the attitude of White supremacy and Black inferiority made the North a poor teacher for the South during Reconstruction and beyond” (In a Blaze of Glory: Womanist Spirituality as Social Witness [Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1995], 51; Townes quotes Leon G. Litwack, North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790–1860 [Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1961], 97).

4. Foote, A Brand Plucked from the Fire: An Autobiographical Sketch, in Sisters of the Spirit, 167. Little is known about Foote’s activities after the publication of her autobiography in 1879.

5. Foote, 167.

6. Foote, 167, 183. According to Laceye Warner, “Foote demonstrated, not only the way in which such prejudice undermines the vitality and integrity of Christian experience among the dominant culture, but also the possibility of debilitating effects for the faith journeys of the disenfranchised” (Saving Women: Retrieving Evangelistic Theology and Practice [Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2007], 108). I am indebted to Warner’s work for first exposing me to Foote as a powerful theologian and preacher.

7. Foote, 183-185.

8. Foote, 185.

9. Foote, 232; 228–29. According to Bettye Collier-Thomas, Foote’s sermon on “Christian Perfection” indirectly criticized perfectionist groups Foote considered extreme, such as the Oneida Perfectionists, the Millerites, and the Prophet Matthias. Foote also disagreed with other female preachers over the doctrine of sanctification, such as Sojourner Truth (a follower of Matthias) and Rebecca Cox Jackson. See Collier-Thomas, Daughters of Thunder: Black Women Preachers and Their Sermons, 1850–1979 (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998), 62.

10. Faced by innumerable daily reminders of their racial and gender unworthiness, black women were, Delores Williams argues, especially drawn to nineteenth-century evangelical Christianity because “this kind of religion helped them put concepts of unworthiness on the side of sin.” Conversion to the Christian religion provided liberation from “unworthiness” to “somebodiness” (“A Womanist Perspective on Sin,” in A Troubling in My Soul, 143).

11. Foote does not use the term segregation in her memoir. I have used it to encompass several segregations that Foote labeled “a prejudiced or sectarian spirit” in regards to racism, sexism, and dissension in society and the church (163). Due to Foote’s recognition of multiple types of segregation, Elaine A. Heath narrates Julia Foote as a protowomanist who denounced the “church’s threefold syncretistic attachment to sexism, racisim, and classism” (The Mystic Way of Evangelism: A Contemporary Vision for Christian Outreach [Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008], 84–100, esp. 89 and 100.

12. Foote, 200. According to Warner, “Foote’s reluctance to accept her call was understandable in light of the fervent opposition expressed toward women’s public speaking. . . . This danger was compounded for Foote and other African-American women preachers by racial prejudice” (Saving Women, 131). Foote’s call to preach in the 1840s occurred during a time of considerable backlash against women’s public speaking in the United States. The public outcry against the abolitionist work of Sarah and Angelina Grimké resulted in the strict banning of women’s preaching and public prayer in many denominations. In addition to this rigidity about sexual hierarchy, denominations such as the Methodists, Freewill Baptists, and Christians were also demanding their clergy to be educated and limiting lay decision making as ways to “help reduce the inherent conflicts of a democratic society.” In the 1840s, uneducated male preachers were being “forced out of ministry,” as these denominations “set stricter limits on lay power” by forbidding women to vote on church business (Catherine Brekus, Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740–1845 [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998], 281–89).

13. Foote, 203. Notice that Foote’s vision is also deeply sacramental. Although Foote never returns to the subject of the Lord’s Supper in her memoir, this vision incorporates the sacraments of baptism and Eucharist within her theology of entire sanctification. That God declares her prepared after undergoing each sacrament implies that all sanctified Christians are prepared to go and tell the gospel, whether or not they receive special visions. These implications further undergird Foote’s defense of her call as part of her general calling as a Christian. God’s singling out of a poor, black woman is not an exception to any rule.

14. Foote, 207. Here, in considering herself a member of the conference, Foote aligns her membership in the denomination with the usual way in which itinerant ministers held membership in the Methodist Conference and not to a local church. Thus, in this one movement, Foote both refuses to be excommunicated and places herself on the same membership level as a male AMEZ preacher.

15. Foote, 214. Foote’s description of her gifts as “weapons not of this world” is a direct reference to Paul’s own description of his preaching in 2 Corinthians 10:4.

16. Foote, 222. Foote reported that in welcoming her to preach, the Zainsville, Ohio, white Methodists allowed African Americans inside their church for the first time. In these gatherings “perfect order prevailed,” while the closed church had also shut the door to Christ, who said “Go, preach my Gospel to all.” Foote also continued to preach in African American churches.

17. Foote, 208. Foote claimed “Christ alone” during moments of feeling alone and disconnected from the rest of Christ’s body because of her calling to preach. Though appeals to Christ alone may sound like a rejection of church tradition and church authority, Foote’s continued preaching within churches and attendance at the annual conference show that she positioned herself as a church reformer. Foote held to traditional doctrines, such as the Trinity, and followed Wesleyan doctrines and traditions. For more on Foote’s orthodoxy and her theological ties to John Wesley’s and Phoebe Palmer’s holiness theologies, see Warner, Saving Women, 117–125.

18. Foote, 218; 227–30. Laceye Warner’s chapter on Foote in Saving Women narrates the emergence of Foote’s insistence on racial reconciliation and women’s ecclesiastic rights as part of her theological framework. These practices cannot be separated from Foote’s evangelistic ministries of visitation and preaching (Warner, 129–40).

19. Foote, 227. Foote’s imagery of the heavenly host echoes the birth narrative in the Gospel of Luke, Pauline epistle language regarding parousia, and the Book of Revelation. Due to her own difficulty in receiving formal education and the absence of much of a historical record of her life outside her autobiography, it is difficult to trace the traditional influences upon Foote’s hermeneutic of scriptural interpretation. Her echoes of Scripture in her narration of life events and her defense of the gospel support her self-identification as a devoted student of Scripture. The echoes also imply that Foote read her life events and her world through the scriptural narrative. More work could be done on Foote’s hermeneutic of Scripture and the numerous scriptural echoes within her memoir.

20. Foote, 210–11. According to Foote, those upset with her group for holding a love feast “seemed to think we had well nigh committed the unpardonable sin” of blasphemy. Foote and her group had chosen a Methodist worship ritual well known for allowing both women and men to share their religious experiences publicly. In quarterly Methodist love feasts, as “many as one hundred or two hundred people could step forward…to share their testimonies” (Catherine Brekus, Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740–1845 [Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1998], 128).

21. Foote once successfully kept her berth by refusing to move, despite a male passenger’s refusal to share an entire boat cabin with her. However, Foote tells of another voyage where she caught a severe cold because rules against nonservant blacks forced her to spend a cold, damp night on deck. Through these examples, Foote exposes the men involved as carrying “dark, slave-holding principles” but directs most of her anger toward the (Satan-like) figure “Prejudice . . . thou cruel monster!” who will exist until the final coming of the reign of God (215, 218). Here, Foote seems to understand the personal and social structures of prejudicial racism and seems to hold a future expectation of heaven coming to earth on the Last Day. In Foote’s memoir, her eschatology is too dynamic to be classified as premillennialism or postmillennialism.

22. Foote, 228. Foote declared that she never lost her sanctification, and those who believe in such a thing believe Satan’s lie about salvation. Instead, Foote blamed her illness on her own withdrawal from God, though God never withdrew from her and eventually brought her back to faith in victory. In this example, Foote interpreted bodily afflictions as signs of her own unbelief or her need for further illumination. In assigning this kind of divine activity over the body, Foote follows a dominant theological strain in Protestant American Christianity. Like Puritanism and other Reformed traditions emphasizing Providence, early American evangelicalism interpreted moments of suffering as moments of divine testing, punishment from sin, or educational trial. Foote reinterpreted this tradition of divine concern over daily life in a new way and combined it with traditional visions of heaven to further assert the gospel of entire sanctification over all bodies and souls.

23. Townes, Womanist Ethics and the Cultural Production of Evil (New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006), 164; 159.

24. Copeland, Enfleshing Freedom: Body, Race, and Being (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2010), 52.

25. Foote, 214.

26. Townes, Womanist Ethics, 165.

27. There is no disembodied theology, though some types of theology hide some types of bodies and, in doing so, distance theology from the body. Theologies that hide certain bodies or ignore the body leave themselves open to be used against certain bodies. See Willie J. Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011) for a theological account of the ways in which the particular body of Christ became hidden, thereby opening the way for supersessionism and colonialism within the Christian theological tradition. Jennings and Foote both emphasize the excavation of these influences within Christian theologies of redemption.