A body affects other bodies, or is affected by other bodies; it is this capacity for affecting and being affected that defines a body in its individuality . . . . That is why Spinoza calls out to us in the way he does: you do not know beforehand what good or bad you are capable of; you do not know beforehand what a body or a mind can do, in a given encounter, a given arrangement, a given combination.

—Gilles Deleuze, Spinoza

Profound respect for both the enrapturing relationality and sheer indeterminacy of bodies now infuses societal concern broadly, but no sphere of modern culture better reflects these fresh concerns with embodiment than contemporary art. Entire movements in contemporary visual art have dedicated themselves to body as a topic for critical discourse in conversation with the intellectual advances made by Gilles Deleuze and others. Along with these new trajectories in art theory, the actual bodies of artists and art participants have been incorporated as artistic fields of endless discovery. Perhaps, the profound alienation that many Christians feel toward the visual art of recent years can be explained by this emphasis on body, an emphasis that the disembodied practices of too many Christians simply cannot receive. Contemporary artists, however, have not in large part sought to avoid such alienation with art audiences more broadly. Visceral confrontations have consistently characterized these recent engagements with bodies in art. Radical and debased representations of bodies in painting, photography, and sculpture seek to dismantle pervasive visual stereotypes and to identify more fully with marginalized bodies. In addition to the social encounters created through the performance and installation art of recent decades, multiple strands of contemporary art repeatedly underscore the inescapable contingency of our embodiment. We are bodies and contemporary art will not let it be forgotten.

Such affronts to ideologies of disembodiment have not only provided a form of resistance in the struggle to narrate our bodies, but they have also opened up new ways of seeing and more fully sensing the immense wonder of embodied life. A select few of these artists have intentionally entered into a dialogue with the Christian tradition and its accounts of body through their art practices. These encounters—in particular the work of Andres Serrano, Chris Ofili, and Kiki Smith—offer more than simply another indictment of the disembodied theologies of contemporary Christianity in the West. Their works also hold out the promise of recovering body knowledge as a sacramental reality in the Christian life. These artists can recall for us the impact of what Deleuze so poignantly said when working through Friedrich Nietzsche: “Perhaps the body is the only factor in all spiritual development.”1

Body in Contemporary Art: A Historical Sketch

The body has been for many contemporary artists an art-historical subject to critique, a focus of ideological conflict, and an instrument of art making itself. For instance, contemporary art has destabilized the once-safe avenues of traditional figuration in painting and sculpture. The painters Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon have complicated and confused the conventions of figure painting in profound ways. Bacon’s ghostly figures emerge from his paintings’ distorted surfaces giving the sensation of a bodily presence but little satisfaction that the subject has been documented in a pretty portrait. In contrast, Freud’s meticulous canvases recall a classical style of figuration in their look—realism’s attention to the minute details of a face or the carefully studied flesh tones of a body—but simultaneously trouble the received impression of an artist’s relationship to his or her model. Freud’s compositions highlight the psychological or emotional tensions evident in his subject’s feelings about being rendered in a portrait. In light of their critical interrogations of painting, Bacon and Freud threaten to mark an end to figure painting in any traditional sense. A younger generation of painters have since followed in their wake and further disrupted the conventions of figure painting. Consider Jenny Saville’s unsettling meditations on flesh as a site of manipulation, violence, revulsion, and gender confusion. Or take the gloriously rendered, but often cartoonishly satirical, sexist fantasies of John Currin.2

Body has also become a site for contemporary artists to engage in important ideological debates. In the tumultuous period of social unrest in Western Europe after World War I and immediately preceding World War II, a renegade bands of unruly artists, poets, and performers in Zurich, Berlin, New York, and other locales exercised an altogether new form of creativity, a movement known as Dada, against the dominant narratives of art making. The nihilist provocations of Dada may have been reviled and misunderstood in their own day, but the seminal influence of artists like Marcel Duchamp, Hugo Ball, Jean Arp, Tristan Tzara, Francis Picabia, and Man Ray issues directly from their formative time in those radical groups. In the 1950s, the groundbreaking efforts of Dada groups were overlooked by many in favor of more traditional modes of art making, but some New York artists, like Carolee Schneeman and Robert Rauschenberg, were experimenting with their own rebellious forms of performance art. These came to be called Happenings and they helped to inspire a similar collective of performance artists in Europe called Fluxus that included the likes of Nam June Paik, Yoko Ono, Joseph Beuys, and others.

These initiatives, along with other neo-Dada offshoots, created an atmosphere of concern for body that opened the door for subsequent artists to more fully concentrate on placing embodied experience at the center of their art practices. Artists like Vito Acconci, Chris Burden, Ana Mendieta, and Marina Abramovi? began testing society’s assumptions about the value and sanctity of bodies by making art almost exclusively out of bodies in pain (e.g., performance art involving self-inflicted biting, piercing, seizures, and even a gunshot wound). In this climate of experimental performance, nearly anything that can be done with or to a body in art spaces has been done, and in this way, contemporary art has led the charge in showcasing the ideological battles to narrate body that still exist in our society. For instance, the provocations of feminist artists like Schneeman and Mendieta have been championed most recently and emphatically by the disruptive critiques of the Gorilla Girls, a collective of artists that don gorilla masks and suits in order to stage dramatic protests against gender and racial hegemony in various art institutions.3

Alongside these trajectories, the relational art of recent decades has made bodies an integral piece of the artistic armature. Although the various movements in performance art continued in successive decades, the 1980s and 1990s saw a rich expansion of art’s engagement with bodies as activist movements responded to the AIDS crisis of the day and as a new generation of artists experimented with the sociality of bodies. Whereas the body art artists of earlier decades utilized bodies as a controversial replacement for traditional art objects, the relational artists of recent decades have instrumentalized bodies as a means of social participation and engagement. The New York artist collective known as Group Material was founded to provide an alternative to the market-driven practices of individual art making through collaborative projects that made art more relevant to social concerns and more accessible to the art public. As a result of these initiatives and others, artists like Félix González-Torres, Rirkrit Tiravanija, and Carsten Höller have made works of art that must be completed by specific bodily interactions, that do not exist after the bodies involved disperse, and that provide no document beyond such interactions. The work of these and many other relational artists indicates that contemporary art is no longer satisfied to merely contest the representations of bodies. Instead, relational art makes way for an art of bodies and for bodies—a pure and indivisibly embodied art.

Dialogue with Tradition

Although these movements represent serious challenges to the disembodied theologies of many Christians today, several artists have engaged body issues not in opposition to Christian accounts of the body but rather because of them. Undoubtedly, the work of Andres Serrano, Chris Ofili, and Kiki Smith attracts controversy—in some cases, even the charge of blasphemy—but these artists are seeking a free dialogue with the Christian tradition through their art, what Eleanor Heartney calls “the Catholic imagination.”4 Such a dialogue, however, cannot help but elicit controversy, because in the case of received notions of embodiment, much needs to be disturbed. The provocations of these artists have opened up new spaces for reflection on the profound contingency of embodied life, what I am calling here body knowledge.

Andres Serrano

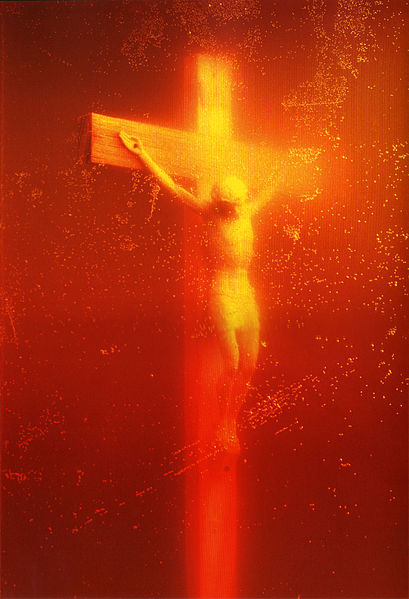

Andres Serrano maintains a form of celebrity all his own in the conversation between religion and modern art5 As a result of the censorship crisis with the National Endowment for the Arts during the early 1990s, he has become a household name in America and a textbook example of the controversial artist/provocateur. Serrano, more than nearly all his peers, will be remembered for one solitary work of art: the Piss Christ photograph. Of course, Serrano has not been shy about revealing his conflicted relationship with the Catholic Church, but contrary to what the angry public might suspect, Serrano’s practice should not be seen as merely blasphemous. It is potentially generative. Serrano has explicitly clarified his art practice in this way: “I don’t really feel that I destroy icons. I feel that I create new ones.”6

Within his series Bodily Fluids, Serrano created a group of photos that involved the submersion of various classical statuettes in a clear container of the artist’s own urine. The photographs demonstrate the artist’s technical virtuosity by lighting the submerged objects without any manipulation of the photos in postproduction. The submerged objects  included a Madonna and Child statuette, a classical female bust, the Discus Thrower, the Archangel Michael, and of course, a crucifix. Each of these statuettes resembles the standard, mass-produced editions that one might easily find at any museum gift shop. Of the range of experiments here in light and color combinations, the Piss Christ photo seems the least interesting. It has few of the soft transitions of color contrast that are seen in the Madonna and Child II photo or the Female Bust photo, but like all the others in this group there is in Piss Christ a depth of rich color value. In Serrano’s rendering, there is an uncanny glow and luminosity to the normally dull and overlooked figurine.

included a Madonna and Child statuette, a classical female bust, the Discus Thrower, the Archangel Michael, and of course, a crucifix. Each of these statuettes resembles the standard, mass-produced editions that one might easily find at any museum gift shop. Of the range of experiments here in light and color combinations, the Piss Christ photo seems the least interesting. It has few of the soft transitions of color contrast that are seen in the Madonna and Child II photo or the Female Bust photo, but like all the others in this group there is in Piss Christ a depth of rich color value. In Serrano’s rendering, there is an uncanny glow and luminosity to the normally dull and overlooked figurine.

Despite the continuity of this group of works, the Piss Christ photo received special attention and intense public ridicule. David Deitcher explains that “Serrano’s photographs are therefore indefensible to so many, not simply because they blaspheme, which, in a narrow sense, some of them do; they are insupportable because they find beauty in substances that have always made people recoil in horror and embarrassment.” Various commentators have viewed this work along a diverse spectrum of meaning, from a purely political reference to the public paranoia over the body’s excretions during the AIDS crisis of the 1990s to a devoutly pious gesture. Amid the diversity of interpretive schemas, Linda Weintraub offers no less than six different options for reading Piss Christ: simple blasphemy, an attempt at refreshing the fact of Christ’s intense humiliation, a defiling of the tawdry figurine and not the figure represented, a test of public tolerance and an affirmation of expressive freedom, a questioning of the sincerity of the public’s reverence for art over religion, and lastly, the offering of a lush image.7

Quite simply, Serrano enjoys the ambiguity that surrounds how the photo should be received.8 As an artist, he seems content to play the role of provocateur, and in the case of Piss Christ, he is provoking the public in general and the Church more specifically to recall the scandalously embodied foundations of Christianity. Serrano offered the following confession in 2003:

I was appalled by the claim of “anti-Christian bigotry” that was attributed to my picture. The photograph—and the title itself—are ambiguously provocative but certainly not blasphemous. . . . My use of such bodily fluids as blood and urine in this context is parallel to Catholicism’s obsession with “the body and blood of Christ.” It is precisely from the exploration and juxtaposition of these symbols that Christianity draws its strength.9

Chris Ofili

Like Serrano’s infamous photograph, Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary received intense scrutiny and public derision because of its shocking surface during the 1999 Sensation group exhibition in New York City.10 For his part, the artist has explained himself in these terms: “My project is not a p.c. project. . . . I’m trying to make things you can laugh at. It allows you to laugh about issues that are potentially serious.”11 Ofili produces a collection of polymorphous cultural icons from often-disparate sources such as hip-hop journalism and branding, ’70s psychedelic funk, Catholic tradition and hagiography, urban fashion, gangsta rap, African artifacts, and blaxploitation films. He provides a visual landscape of black culture that is at once devoid of cultural hierarchy and literally dripping with colorfully sexy, ethereal splendor. Klaus Kertess describes Ofili as an artist who “renders holy sexy and vice versa.” He explains further that “Ofili provides aesthetic pleasure in generous portions but intends that pleasure to draw the viewer in to question and/or reconsider conventional beliefs.”12 Although his body of work envelopes all manner of cultural touchstones and privileges none, the emergence of his thoroughly Africanized Madonna in 1996’s The Holy Virgin Mary represents the most difficult cultural translation of that icon in recent memory.

Any analysis seeking to unify the work and understand Ofili’s distinct strategy must hold in tension the disparate references contained within this work. On the one hand, Ofili’s Virgin appears robed in a lovely blue, the traditional color of Mary’s mantle, and floating on a golden background with dotted lines of monochromatic gold radiating a halo from herhead, two traditional indicators of divinity in iconography. On the other hand, this Virgin displays exaggerated African facial features and the contours adorning her form resemble what the artist describes as “vaginal shapes, flowery.”13 Like all of the other works from this period in Ofili’s career, the painting utilizes large balls of elephant dung that are covered in resin and applied to the canvas. As with other canvases, two dung balls support the canvas of The Holy Virgin Mary as it leans against the gallery wall, and the exposed breast of the Virgin has a large dung ball indicating her nipple. Barely noticeable in the work, Ofili has intermittently scattered on the splendid gold atmosphere of the Virgin round cutouts of naked female buttocks from pornographic magazines. These cutouts of various sizes and hues resemble winged insects hovering about the figure. For Ofili, they stand in for butterflies, but in these same shapes, Heartney sees a clear reference to the nude putti of so many Renaissance depictions of the Virgin. Ofili explains the convergence of disparate imagery in The Holy Virgin Mary in this way:

One of the starting points was the way black females are talked about in contemporary gangsta rap. I wanted to juxtapose the profanity of the porn clips with something that’s considered quite sacred. It’s quite important that it’s a Black Madonna. . . . I wanted to make a ’90s version of the Holy Mary, an in-your-face ’90s version of Christ’s mother. . . . I really think it’s a very beautiful painting to look at, full of contradictions, which is perhaps why it’s been misunderstood.14

Here, Ofili exercises his own freedom as an artist from the political dialectic of multiculturalism. He creates the visual landscape that he wants to see, and oddly enough in this landscape, he makes room for the Virgin Mary. Cleary, his depiction constitutes a highly sexualized Virgin, celebrated chiefly for her potent sexuality and fertility. The gesture behind her representation, however, remains significant, for the irrepressible trace of the icon comes through as well. Social propriety dictates a strict separation of the spiritual from the sexual, but Ofili’s painting doesn’t simply reject this separation. His Madonna pokes fun at the way in which either extremes— Victorian prudishness and multiculturalism’s permissiveness—seek to make body knowledge subservient to purely ideological concerns.15

Kiki Smith

Kiki Smith manages to elude easy categorization. Numerous associations surround her work: for example, participation in Collaborative Projects’ (Colab) legendary 1980 Times Square show in New York City, identification with the craft-making art practices of the 1970s and 1980s feminist critique, and contributing to the revival of figurative sculpture in postmodern art.16 Smith grew up in the home of two working artists and with a small gang of artistic collaborators in her twin sisters. Before raising a family, her mother had acted on Broadway and sung opera, but her father, minimalist sculptor Tony Smith, enjoyed a long and celebrated career in the art world. Tony Smith had received training from the Jesuits and his wife was a convert to Catholicism. They elected to raise their children in that faith, and the culture of theirhome was not only infused by the parents’ activity and background in the arts but also by the visual-spiritual aesthetic of their Catholic faith.17 Thus, her childhood laid the foundation for her intensely spiritual and, at the same time, intimately tactile perspective on the arts. Her practice consists more in an inductive exploration rather than a deductive exercise, and in that approach, body became a point of convergence for the dual influence of her Catholic imagination and her political consciousness. Her father’s generation had abandoned body as territory already covered by naturalism in the arts, but for Smith the sensibilities of feminism and the spirituality of Catholicism came together to offer her a fresh perspective on the human form:

In working with the body, I feel I’m actually making physical manifestations of psychic and spiritual dilemmas. Spiritual dilemmas are being played out physically. That puts me in a Catholic tradition, but in Catholicism there’s a fetishizing of experience—there’s empathy for suffering but also an artificiality: the suffering is removed and objective. And I think you have to look at everything as interrelated. One’s inner life is not separated from one’s social life, one’s gender, one’s political life. That’s the feminist model. Most of the time when I talk to women, that’s what I see: the social and the intellectual and everything else constantly melding and falling into each other.18

Smith draws upon a host of images and icons from the cultural collection of common myths and preconceptual knowledge of ourselves; she draws from fairy tales, folklore, and perhaps most significantly, the biblical stories of the Christian tradition. Indeed, one of Smith’s most potent realizations of the synthesis described above appears in her treatment of iconic saints in the Christian tradition. In her choice to reimagine biblical figures like Eve, the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and Lot’s wife and mythical characters like Lilith, she seeks to address the unfortunate artificiality she detects in Catholicism, a violence she sees directed at the bodily suffering of women.

Likely the most visually arresting piece in Smith’s oeuvre, her Virgin Mary of 1992, consists of a life-size écorché, a figure rendered without skin for the benefit of exposing the muscular structure. Made of wax and cheesecloth, this sculpted écorché demonstrates the traditional, diminutive posture of her iconic namesake. Smith describes the evocative nature of the pose: “There are certain poses of the Virgin Mary, with her arms out to the sides, and if you actually stand that way, it opens you up and makes you vulnerable, maybe even compassionate.”19 Amid the near horror of exposed muscle tissue and fat deposits that are made poignantly realistic through the deep red hues and pale nude tones of the wax, this Virgin bears the violent scorching of divine visitation and at the same time demonstrates the resolve and internal strength to stand and receive with submission what the Lord offers. In this way, Smith grants the viewer a sense of the Virgin’s unique body knowledge.

Likely the most visually arresting piece in Smith’s oeuvre, her Virgin Mary of 1992, consists of a life-size écorché, a figure rendered without skin for the benefit of exposing the muscular structure. Made of wax and cheesecloth, this sculpted écorché demonstrates the traditional, diminutive posture of her iconic namesake. Smith describes the evocative nature of the pose: “There are certain poses of the Virgin Mary, with her arms out to the sides, and if you actually stand that way, it opens you up and makes you vulnerable, maybe even compassionate.”19 Amid the near horror of exposed muscle tissue and fat deposits that are made poignantly realistic through the deep red hues and pale nude tones of the wax, this Virgin bears the violent scorching of divine visitation and at the same time demonstrates the resolve and internal strength to stand and receive with submission what the Lord offers. In this way, Smith grants the viewer a sense of the Virgin’s unique body knowledge.

Whereas Smith’s Virgin Mary delves into the bodily sacrifices of a revered religious figure, her Mary Magdalene charts an entirely new trajectory for traditional hagiography.20 As inspiration for her work, Smith explicitly references the fact that female saints seem to have their innate sexuality severed from them in light of their spiritual service. In response to this one-sided tradition, Smith seeks to repair the sexuality of Mary Magdalene and produces an altogether newcompromise.21 Of the work, Thomas Baltrock relates, “Her Mary Magdalen is no saint, but equally the figure is not a feminist statement.”22 Indeed, the life-size bronze statue maintains, at once, the dual nature of feminine loveliness and primitive creatureliness.23 Thus, her Mary Magdalene becomes a poignant foil for her Virgin Mary; the female sexuality that God has eclipsed in the body of the Virgin has been restored and released back to a natural delight in the Magdalene, evidenced by her self-sustaining covering of hair and the fact that the chain attached to her ankle has been broken. The juxtaposition of these two figures may suggest a sense of liberation and freedom available only to the Magdalene, but there remains in the Virgin’s tortured flesh a sign of mystical union with God.

These carefully nuanced re-creations of iconic saints in the Christian tradition hold out both the promise of  transcendence and the acknowledgment of the sacrifice, loss, and pain contained within their spiritual journeys. Thus, Smith offers her viewers a mixed bag of affirmations: body knowledge both signifies the spiritual telos of life and the persistent hardships known only to the present body; here, everyday existence knows too well the in-breaking of both heaven and hell. The picture of grace in Smith’s work therefore remains bound to the extraordinary fragility of this life. Displayed in her obsession with corruptible, everyday objects and materials, Smith demonstrates what Marina Warner calls “a love of humble, quotidian forms and processes . . . [that] do not claim to surpass life through art’s power, but only to stumble after organic vitality with every clumsy means at her disposal.”24 Smith’s Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene represent a revolutionary attempt at reconciling body knowledge more fully with the irrepressible wisdom of the artist’s experience in the Christian tradition.

transcendence and the acknowledgment of the sacrifice, loss, and pain contained within their spiritual journeys. Thus, Smith offers her viewers a mixed bag of affirmations: body knowledge both signifies the spiritual telos of life and the persistent hardships known only to the present body; here, everyday existence knows too well the in-breaking of both heaven and hell. The picture of grace in Smith’s work therefore remains bound to the extraordinary fragility of this life. Displayed in her obsession with corruptible, everyday objects and materials, Smith demonstrates what Marina Warner calls “a love of humble, quotidian forms and processes . . . [that] do not claim to surpass life through art’s power, but only to stumble after organic vitality with every clumsy means at her disposal.”24 Smith’s Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene represent a revolutionary attempt at reconciling body knowledge more fully with the irrepressible wisdom of the artist’s experience in the Christian tradition.

Body Matters

A final comparison is in order here. With his magisterial study of sexual renunciation in early Christianity, Peter Brown describes the aim of his book The Body and Society as giving back to the men and women of the church’s first five centuries something of the “disturbing strangeness of their most central preoccupations” with their bodies.25 Perhaps, in addition to feeling a vast cultural distance from figures like Saint Thecla or Saint Antony, the church of recent years has lost its awareness of that disturbing strangeness entailed in Christian discipleship. Rather than reviling their bodies, Brown explains that representative ascetics like the desert fathers “imposed severe restraints on their bodies because they were convinced that they could sweep the body into a desperate venture,” and these embodied journeys were directed toward “the eventual transformation of their own bodies on the day of the Resurrection.”26 The question remains for Christians in every generation since: How might we renew such an embodied hope today? Perhaps, a similarly radical and no less embodied protest is necessary in this age.

In many ways, there is profound continuity between the challenges the desert monks faced and what we encounter today. The most potent threats to Christian views of embodiment are often cast in terms of care for bodies. In the ancient world, a body was just another cog in the machinery of empire, and although the empire’s appetites could not be denied they needed direction. Specifically, the subjugation of bodies in marriage went a long way to meet the population demands of a great empire and fulfill the requisite forces necessary to protect it. Today, the civil religion of empire has been replaced by the tyranny of consumer comforts and bodily enhancements, and the primary enemy of our age is not the barbarians at the gate but rather the formidable adversaries of ugliness, aging, sickness, and death. Just as Gnostic tendencies plagued the first-century church by encouraging a fatalistic hedonism, the quest for bodily perfection here and now threatens to undermine genuine care for the dignity of actual bodies and any of the distinctiveness in embodied Christian practices. Has the church understood that the implicit Gnosticism of consumer-driven bodily enhancements is no less insidious than the original heresies that the Apostles opposed? If so, the practices of the church will show it.

While the desert fathers and mothers of early Christianity disciplined their bodies in the wilderness in order to save the soul of the church, the body art artists of today are retreating to the space of contemporary art to question again the old assumptions about bodies. For artists like Andres Serrano, Chris Ofili, and Kiki Smith, body is no longer a necessary evil of our existence but rather an integral component of our redemption and renewal together with Christ and with his saints. In their austere and idiosyncratic fashion, these artists have recalled the transformational strangeness of early ascetics and martyrs. Bodies do not belong to other bodies; bodies do not belong to the state or the market. Bodies belong to the Lord, and in this freedom they bear witness to the grace of Christ. Just as Brown’s The Body and Society narrates Christian accounts of embodiment that do not fit with modern stereotypes, these artists help to recall the strangeness of such views in another way, and with their provocative works they defamiliarize us with bodies only to return us to the wonder of them once more. In such art works, it is clear that Christians today must account for body knowledge in fresh ways and recover their own bodies as the place for anticipating Christ’s re-creative work.

1. Deleuze, Nietzsche and Philosophy, trans. Hugh Tomlinson (London, UK: Continuum, 1983), 39.

2. Both Saville and Currin are represented by Gagosian Gallery, an elite international art dealer with a network of galleries in several countries. To learn more about Saville, visit http://www.gagosian.com/artists/jenny-saville, and to learn more about Currin, visit http://www.gagosian.com/artists/john-currin.

3. To learn more, visit http://www.guerrillagirls.com.

4. My consideration of these artists has benefited from the work of Heartney, in particular her volume Postmodern Heretics: Catholic Imagination in Contemporary Art (New York, NY: Midmarch Arts, 2004), 143.

5. Serrano has consistently examined a host of traditional religious topics and symbols in his photography. His bodies of work include politically charged attempts at tableaux vivants (e.g., The Church, The Interpretation of Dreams, and the History of Sex series) involving controversial juxtapositions of nude victims; raw meat; classical Christian symbols and representatives of the ecclesial hierarchy; studies of light through the lens of bodily fluids like urine, blood, milk and semen; and provocative portraiture, as in the case of the Nomads series, The Klan series, The Morgue series, and his recent collection of over one hundred portraits, America. To learn more about the artist, visit http://andresserrano.org/. To view the Piss Christ photo, visit http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Piss_Christ_by_Serrano_Andres_(1987).jpg.

6. Shayne Bowman, “‘Initial Shock Wears Off’ from Serrano’s Work,” Auburn Plainsman, May 16, 1991, B1. Similarly, with Christian Walker, he states that “I’ve never considered myself an activist, a champion of any sort of in the social realm. I like to think in terms of raising more questions than answers” (Serrano, “Andres Serrano interviewed by Christian Walker,” in Glenn Harper, Interventions and Provocations: Conversations on Art, Culture, and Resistance, SUNY Series, Interruptions: Border Testimony(ies) and Critical Discourses [Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1998], 116).

7. Deitcher, “Cumulus from America,” Parkett 21 (Fall 1989): 142; Weintraub, Art on the Edge and Over, 162–4.

8. Heartney perceptively acknowledges the formal and conceptual unity of the work that in turn inspires such a diversity of readings. She explains that Piss Christ and the other works from the Bodily Fluids series “employ physical substances both for their beautiful effects and for their cultural, historic and religious meanings. To substitute some other material would have undermined their aesthetic and conceptual power” (“Looking for America,” in Serrano, America and Other Work [London, UK: Taschen, 2004], np).

9. Serrano, “Ambiguously Provocative,” Conscience: The Newsjournal of Catholic Opinion, Art, Religion and Censorship Roundtable, March 2003. He continues, “The photograph in question, like all my work, has multiple meanings and can be interpreted in various ways. So let us suppose that the picture is meant as a criticism of the billion-dollar Christ-for-profit industry and the commercialization of spiritual values that permeates our society; that it is a condemnation of those who abuse the teachings of Christ for their own ignoble ends. Is the subject of religion so inviolate that it is not open to discussion? I think not.”

10. Ofili is represented by Victoria Miro Gallery in London (http://www.victoria-miro.com/) and David Zwirner in New York (http://www.davidzwirner.com/). To view Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary, visit http://www.davidzwirner.com/artists/chris-ofili/survey/image/page/54/.

11. Ofili interviewed by Kodwo Eshun, “Plug Into Ofili,” in Chris Ofili, by Lisa Corrin, Chris Ofili, and Godfrey Worsdale (London, UK: Serpentine Gallery, 1998), np. Worsdale claims that “Ultimately, to engage fully with the work it must be experienced as a group of complex, conflicting and sometimes deceptive possibilities rather than a statement of uncompromising intent” (Worsdale, “The Stereo Type,” in Chris Ofili, 10).

12. Kertess, “Just Desserts,” in Devil’s Pie, by Angela Choon, Klaus Kertess, Chris Ofili, and Cameron Shaw (New York, NY: Steidl and David Zwirner Gallery, 2008), np. Any assessment of Ofili’s painting should be tempered by the fact that commentators of his work repeat the claim that Ofili remains a practicing Catholic. See, for example, Heartney, Postmodern Heretics, 143.

13. Corrin, Ofili, and Worsdale, Chris Ofili, np. Concerning the cutouts hovering about the Virgin, Moyo Okediji remarks, “take a look at several Yoruba representations of female divinities, including Oshun, Yemoja, and Olokun sculptures, and tell me if you would not find pointed breasts and open vaginas boldly displayed by the artists.” Similarly, John Peffer sees a potent unity of themes represented in the painting: “For the Swazi the honorific for the Queen Mother is Ndlovukati, for the Zulu it is Ndlovukazi. Both translate as ‘Lady Elephant.’ What an apt title for Mary too, that very reverenced Queen Mother of the Catholics” (Quoted in Donald J. Cosentino, “Hip-Hop Assemblage: The Chris Ofili Affair,” African Arts 33, no. 1 [2000]: 43–44). Compare this composition with Ofili’s Blossom, 1997.

14. Ofili also theorizes about classical Western depictions of the Virgin’s sexuality: “The exposed breast is hinting at motherhood but those images are very sexually charged. She’s painted as this beautiful, passive, angelic woman, pure and very attractive looking. I think the Virgin Mary was an excuse for pornography in the homes of these holy priests and Godfearers” (Corrin, Ofili, and Worsdale, Chris Ofili, np).

15. Worsdale discusses the unexpectedly subtle genius of Ofili’s unavoidable experiment in controversy: “For the artist, a misunderstanding of this painting is not symptomatic of the work’s failure, in fact Ofili argues that it is within the misunderstanding that the work exists. Political correctness is purposefully unsustained” (“The Stereo Type,” Chris Ofili, 8).

16. Smith is represented by Pace Gallery (http://www.pacegallery.com/). In the introduction to the catalog for the recent touring retrospective Kiki Smith: A Gathering, 1980-2005, Siri Engberg describes her practice in this way: “Smith marginalizes no medium, whether she is working in plaster, wax, glass, paper, porcelain, bronze, photography, printmaking, or a host of other materials and techniques that form her complex and very personal vocabulary” (Siri Engberg, Linda Nochlin, Lynne Tillman, and Marina Warner, Kiki Smith: A Gathering, 1980-2005 [Minneapolis, MN: Walker Art Center, 2005], 19; also see Chuck Close, “Kiki Smith,” Time 167, no. 19 [2006]: 170). Colab included such prominent artists from the period as Jenny Holzer, David Hammons, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat and others—see Heartney, ed., After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art (New York, NY: Prestel, 2007), 191. See also David Little, “Colab Takes a Piece, History Takes It Back: Collectivity and New York Alternative Spaces,” Art Journal 66, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 60–74.

17. In an interview with David Frankel, Smith relates the significance of her Catholic upbringing: “I was very influenced by the lives of the saints when I was a kid—you have a body with attributes and artifacts evoked by a sort of magic. Catholicism has these ideas of the host, of eating the body, drinking the body, ingesting a soul or spirit; and then of the reliquary, like a chop shop of bodies. Catholicism is always involved in physical manifestation of physical conditions, always taking inanimate objects and attributing meaning to them. In that way it’s compatible with art” (Smith, “In Her Own Words: Interview by David Frankel,” in Helaine Posner, Kiki Smith, and David Frankel, Kiki Smith [Boston, MA: Bulfinch, 1998], 38). Also see Michael Kimmelman, “The Intuitionist,” New York Times, November 5, 2006; and Smith, “Kiki Smith/Chuck Close,” in Betsy Sussler, Suzan Sherman, and Ronalde Shavers, Speak Art!: The Best of Bomb Magazine’s Interviews with Artists [New York, NY: New Art, 1997]).

18. Posner, Smith, and Frankel, Kiki Smith, 32. Along these lines, Heartney elucidates the idea of woman as nature in Smith’s oeuvre: “In Smith’s work this idea manifests itself through a focus on the body that travels from the inside out. She rejects the Western world’s long-standing tendency to privilege vision over the other senses and to charge artists with the task of creating an objective representation of the visible realm. Instead, she expresses a corporeal sense of reality in which taste, touch, and smell are as important as sight. For Smith, knowledge is subjective and cannot be separated from our sensate experience of the world” (“Kiki Smith: A View from the Inside Out,” in After the Revolution, 194–5). To view Smith’s Virgin Mary, visit http://www.sfmoma.org/explore/collection/artwork/22705.

19. Smith in Michael Kimmelman, Portraits: Talking with Artists at the Met, the Modern, the Louvre, and Elsewhere (New York, NY: Random House, 1998), 73.

20. Consider the following depictions set on a spectrum from extreme modesty and almost unnoticeable humility, as in Perugino’s Galitzin Triptych of 1485, to what appears to be a form of bodily penance in Donatello’s wood-carved sculpture of 1454–55. To view Smith’s Mary Magdalene, visit http://womeninthearts.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/smith-mary-magdalene.jpg.

21. Heartney explains the artist’s gesture in terms of acknowledging and correcting Donatello’s vision of the saint. She writes, “Depicting the Magdalene as a wild, almost animal like creature in her later years as a hermit in the desert, Smith pays homage to Donatello’s famous version of this subject. However, while Donatello dresses Mary Magdalene in tattered garments that hang loosely over her emaciated body, Smith depicts her naked, with a hairy voluptuous body, as if she had become resexualized by her return to an animal state” (Postmodern Heretics, 159).

22. Baltrock, “Both Ancient and New: Works by Kiki Smith in St. Peter’s, Lübeck; Reflections of a Theologian,” in Smith and Baltrock, Kiki Smith: Werke/Works, 1988-1996 (Cologne, Germany: Salon Verlag, 1998).

23. Smith describes the project in this way: “In the park [in Düsseldorf] there is a big column with a statue of the Virgin Mary on top of it. I thought it’d be nice to make a sculpture of Mary Magdalene as a primitive woman, maybe with a chain on her leg, looking up at this statue of the Virgin Mary. In Southern German sculpture, from the early Renaissance and the Gothic stuff, Mary Magdalene is portrayed as a wild woman. They had hairy, wild men in German folklore too, like dancing bears. I used the wax to sculpt the hair. Her face and bosoms, hands and feet, knees and elbows are smooth, but then the rest is all hairy” (Smith in Sussler, Sherman, and Shavers, Speak Art!, 147).

24. Warner, “Wolf-girl, Soul-bird: The Mortal Art of Kiki Smith,” in Engberg, Nochlin, Tillman, and Warner, Kiki Smith, 46.

25. Brown, The Body and Society: Men, Women, and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity, Twentieth Anniversary Ed. (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2008), xv.

26. Ibid., 222.