Art by Justin Bower; Essay by Jocelyn Grau

We live in a world where individuality is rapidly fading. Information is so effortlessly accessible to a vast number of people that our concepts of self, distance, and visual difference are disappearing. Justin Bower’s paintings invoke the most unnerving edge of our own tendencies and fears. He conjures the possible loss of our physical selves.

Portraits were originally intended as both a likeness of their subject and a physical stand-in for that person. They were both human and object simultaneously, an incarnation and a representation of the flesh. This unique characteristic allows portraits to exist within a space of magical paradox. Justin Bower’s paintings do not call this space into question. Instead, his paintings question whether the subjects of his portraits were in fact ever living.

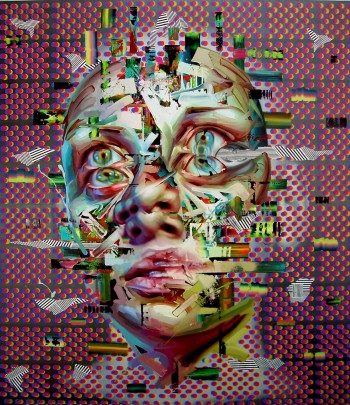

Moving among Bower’s paintings is an unhinging experience. Each painting is a frontal portrait of the same face: a no-man or an everyman. We are not sure. We are only sure that many pairs of the same eyes are tracking us. Blank, dead, duplicated—these ruined eyes follow us, asking no questions, giving no answers. They simply stare, mutely, from their lush paint surfaces, long past the point of engaging their observer. Their faces are bruised and brutalized, cut apart and re-formed through bright and otherworldly marks. Paint seems to actively dissect each face at every turn, ripping their flesh apart with each precise incision of paint.

Our response to these portraits, all cold stares and flayed skin, is entirely personal. However, their meaning hovers around the identity of Bower’s subject. On one hand, the everyman can be seen as universal, as an allegorical representation of every viewer. In this case, Bower’s paintings can be read as a portrait of all people who live in a society where technology and media bombard them daily, where the world they live in is systematically dissecting them through advances in technology, distancing them from the flesh being hewn from their bones.

On the other hand, these otherworldly images can also be seen as a no-man—someone existing outside the self of the viewer. Here, the paintings do not project a living, breathing presence. Rather, they appear lifeless, their yielding alien flesh being investigated for the secrets it might hold.

But what if a third type of subject exists? What if the subject is neither an allegorical representation of each viewer nor an alien thing being experimented upon? What if, in fact, each everyman is alive and is unaware of its own vivisection? Here, the paintings parade an endlessly repetitive illustration of someone who is so removed from their physical being by technology that they are only vaguely aware of their own suffering.

Bower’s repetition and recycling of the same face is troubling. By repeating nearly the same image, he forces viewers to call their own sense of self into question while also forcing them to distance themselves from the image. The many ways he dissects and vivisects the same face pulls viewers out of sympathy with the subject and forces them to see each face as more of an object and less of a human. In effect, he raises a mirror to viewers, asking us to assess our guilt in allowing our own originality to fade.

Aside from being troubling, a drawback to Bower’s use of repetition is that it quickly has a sedating effect. Much of the horror and violence of his work slowly turns to seductive beauty and numbs viewers to its macabre nature.

In the end, Bower’s work forces us to pick our poison. It asks us to locate ourselves within his subject—to respond in sympathy to his everyman, to remove ourselves from his no-man, or to willingly accept the distance technology has begun to put between ourselves and our flesh. Bower’s paintings absorb us into their surface. They suck us up with their lush color and beautifully violent paint marks and then push us away as we take in their repulsive implications. Throwing us outward, they sedate us to their violence and foreboding warnings. We stand mesmerized, seduced and entranced by Bower’s gorgeous surfaces and marks, slowly forgetting our flesh and our transgressions against ourselves.