People don’t want to see clothes. They want to see something that fuels the imagination.

—Alexander McQueen

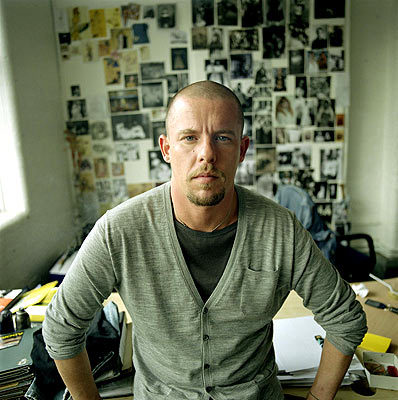

It has been over three years since the death of fashion designer Alexander McQueen, the man who invented the low-rise jean. The loss is sure to go unnoticed or to curry bewilderment among those who observe writers like myself grieving the man’s absence. But those who are familiar with McQueen’s achievements know better. McQueen was one of the most celebrated fashion designers in recent history, an artist whose critically acclaimed work made him a four-time winner of the British Designer of the Year Award. His designs formed the backdrop for our lives. They were donned by Madonna, Penelope Cruz, Nicole Kidman, Sarah Jessica Parker, Björk, Lady Gaga, and Rihanna and then found their way (even if unknowingly and mostly as knockoffs) to closets around the globe. They were showcased in museums and studied by the academy.1 But McQueen’s most notable achievements were his catwalks. His models were placed inside giant chessboards, painted by robotic Jackson Pollock–like machines, and replaced by translucent moving mannequins; they strutted through war scenes with crucifixes strapped to their foreheads, circled piles of rubbish on a shattered glass runway, and rode merry-go-rounds; they were engulfed in flames, showered by waterfalls, stuck through with spears, and dropped into circus rings. These outlandish, thematically driven catwalks-turned-performance-art were the heartbeat of McQueen’s career, and it was in these performances that McQueen presented us with a theologically haunted vision of the body.

Miraculous Bodies

In his spring/summer 1997 runway La Poupée (“The Doll”), McQueen turned to the blatantly theological image of models walking on water. These were his miraculous bodies—beautifully dressed women enacting the impossible. And yet, a number of the models were saddled with jewelry that restricted their movement. Inspired by the German artist Hans Bellmer’s poupée—a project in which Bellmer deconstructed and reconstructed dolls for a series of photographs—McQueen seemed to be inviting his audience backstage to see his dubious role as one who creates dolls that, through a carefully crafted performance, could present a supernatural body. The message emerging from the catwalk was a familiar one for McQueen: in spite of the miracle-working power of fashion, we must see beyond exquisite prints and culturally sanctioned forms to the truth.

What was this truth? Among the graceful “Aryan dolls” (Bellmer’s work was in reaction to Nazi eugenics) who glided across the water, puppet master McQueen included black model Debra Shaw who, constrained in body jewelry that looked like manacles attached to her arms and legs, moved in a contorted and robotic manner down the runway. Denying that the reference was to slavery, McQueen claimed he was attempting to reproduce the puppet-like movements of a doll. Through Shaw’s performance, McQueen challenged the fascism of fashion, its stringent boundaries of what was considered “put together,” and how such boundaries ended up constricting the body, making the exterior impose upon the interior. McQueen used such constriction to reveal fashion’s inability to transit between the external body and the internal person, between the visible and the invisible. Ironically, McQueen’s bodies simultaneously suggested and denied the miraculous body.

McQueen’s miraculous bodies appeared once again in his spring/summer 2000 collection. There, his models, voluminously draped in solid, striped, and mixed gowns, took flight, flying above audience members in graceful, acrobatic, and meditative poses. They created the illusion of glorified bodies soaring above mere mortals. One recognizes in such bodies echoes of Scripture: “For this perishable body must clothe itself with the imperishable, and this mortal body with immortality” (1 Corinthians 15:53 NIV).2 But again, McQueen’s soaring creations were more than resplendent bodies set within an idea of hope. Always multilayered in his approach, McQueen added several dramatic elements to problematize this vision of perfection. For example, a menacing bed of massive spikes positioned underneath the flying figures meant that such feats intimated not only a soaring hope but also a foreboding terror. Then, at one point in the performance, two of the models were overcome by a fitful dance, which seemed to suggest a deep disturbance within the elevated women. And finally, the models were joined by black-frocked figures wearing burkas, implying that the aerial displays were as much about a flight from religion (and, perhaps, its constricting gender norms) as a vision of a miraculous body.

Transformed Bodies

McQueen also transformed bodies, often in ominous fashion. Exemplary of this were the Alice-in-Wonderland-like, surreal creatures strutting the catwalks of McQueen’s The Horn of Plenty show. Here McQueen’s models wore garbage cans, used lampshades, or discarded umbrellas; their faces were painted ghostly white, and their lips were enlarged with bright red lipstick reminiscent of blow-up sex toys. What’s more, by recapitulating similar styles on a circular runway without blurring the distinction of the various outfits and the antics of each character, these freakish creatures evoked the idea of an insane repetition. The show was McQueen’s self-critique of the deformative powers of consumerism, particularly the way in which fashion is endlessly and consciously driven toward an environmentally destructive obsolescence.

In answer to The Horn of Plenty, McQueen’s spring/summer 2010 Plato’s Atlantis revealed a very different transformation. The show began with a giant video screen displaying the torso of a woman writhing in the sand. As the video continued, snakes spilled over the woman until she was covered in their twisting bodies, and then the woman and the snakes were engulfed in water. The result of this bizarre snake-meets-woman reverse evolution became apparent when models emerged marching across a sparkling, mother-of-pearl hued runway dressed in short, reptile-skin-patterned, digitally printed dresses. These futuristic creatures suggested a cross between translucent sea nymphs and postapocalyptic superhumans. Their massive, intricately designed stilettos simultaneously referenced the grace of ballerinas en pointe and a large, menacing crustacean claw,3 with the blending of beauty and a dangerous sublime being further evoked by “hair braided into barbaric horn shapes and corn rowed like archaic Greek goddesses.”4 Through such arresting designs McQueen sought to relay the phantasmagorical story of a future rediscovery of Atlantis in lieu of humanity seeking to survive earth’s melting polar caps. As McQueen relayed, “We came from water and now, with the help of stem cell technology, we must go back to survive.”5

Beautiful Bodies

Finally, McQueen’s work was propelled by what he perceived as the untapped beauty latent in the body. McQueen was known for tailoring stunning garments that highlighted the body’s form within well established genres: the perfectly fitting sports jacket or the stunning little black dress. But McQueen became best known for cuts that revealed parts of the body that are not typically highlighted. Believing that “beauty can come from the strangest places,” McQueen found himself “trying to trap something that wasn’t conventionally beautiful.”6 This struggle with socially constructed standards of beauty was a quest for something more, and it provided the impetus for one of McQueen’s most celebrated shows, his spring/summer 2001 Voss show.

McQueen set the stage for his Voss show by placing a large reflective plexiglass box in the middle of the runway while showering harsh light on the fashion media that filled the audience. By intentionally starting the show late, McQueen forced the arbiters of beauty to confront their own reflections. The result was an increasingly uncomfortable self-consciousness that left the fashion media that filled the audience with one of three options: look away, watch themselves, or watch others watching themselves. Describing the event, Caroline Evans explained that “McQueen reduced the observers to objects, turning their own sharp scrutiny of the models back on themselves, highlighting how much the model, as well as the clothes, are objectified in the gaze of the journalists.”7 McQueen continued the gestalt shift by changing the lighting so that the reflective effect moved from the audience outside the glass box to the models inside the box. Playing the part of voyeurs, the audience now watched as models responded to their reflection with the kind of preening and personal inspection akin to one’s self-observation of the body in the privacy of a bedroom mirror.

Accenting the narcissism of the models, McQueen instructed them to increasingly appear psychotic in their search for a socially acceptable beauty. As the drama unfolded and the show progressed, their beautifully wrapped heads began to take on the appearance of bandages; the fetishized material used for apparel began to resemble the collections of ragpickers (i.e., feathers, shells, strips of cloth). One observer wrote, “The creepy idea began to sink in that we were being treated to a performance by some of the world’s top models about beautiful women driven insane by their own reflections.”8 After the last model exited the plexiglass box, the walls of a smaller box on the runway collapsed, revealing a heavyset nude woman covered in live moths, her head encased in a metal, piglike mask attached to a breathing tube.9 The taboo of a fat moth-covered body (think of moths eating clothing) contrasted with the skinny, meticulously dressed psychotics juxtaposed the attractive power of clothing to accent the body’s aesthetics with the horror, oppression, and insanity that the pursuit of a beautiful body can take. McQueen’s quest for an undiscovered beauty alongside his criticism of its counterfeit resulted in a deep-seated ambivalence that surfaced throughout his career; one sees it in his bedecked beauty outcasts, such as amputees and Indians from the subcontinent (who before McQueen had never been used on British runways), and in his incorporation of identical twins in his Overlook show.

Romanticism and Resurrection

Andrew Bolton has argued that McQueen’s work should be identified as a contemporary form of Romanticism.10 In light of Bolton’s claim, philosopher Charles Taylor’s work on the genesis of contemporary Romanticism proves quite helpful for assessing McQueen’s project. In A Secular Age, Taylor seeks to capture what it feels like to live in our contemporary secular Western society, a society in which belief in God has become “one option among others, and frequently not the easiest to embrace.”11 Taylor claims that in spite of its ever-increasing fragmenting, pluralizing, and fragilizing options, our age remains inconclusively haunted by a sense of loss and malaise concomitant with secular disenchantment. Given that we moderns are immersed in such fraught dynamics, Taylor sees us as torn between the immanence of disenchantment on one side and the significance of a potentially lost transcendence on the other. As a result many people today—not just “card-carrying theists”—find themselves suspecting that a greater “fullness” may yet be found, “a third way” between a purely immanent frame and religious faith.12

For Taylor, contemporary suspicions of “fullness” find their immediate source in nineteenth-century Romanticism. As unbelief reached a critical mass in the nineteenth century, people found themselves adrift in a cold, anonymous, cavernous, infinite space (rather than place) that was marked by an increasingly secular experience of flattened time. Uncomfortable with the ruthless leveling of instrumental reason, Romanticism provided an immanent mystery by which we can deal with “the feeling that there is something inadequate in our way of life, that we live by an order which represses what is really important.” Victorians were pulled between an inability to believe the old Christian faith and an unwillingness to give into a purely mechanical and material universe devoid of depth and fullness, and so they turned to the healing power of an aesthetic life. Forsaking both self-imposed exploration into one’s despair and Byronesque self-affirmation of defiance, these Romantics held out an Emersonian hope for a new age able to realize “a harmonious perfection, developing all sides of our humanity.” As Taylor explains, the Romantic impulse was especially evident in the way the arts increasingly took on a creative “world-making” element of their own. In doing so, the arts afforded a way to address a lost transcendence without returning to religion per se (although religion was not necessarily eliminated), and thus, Romanticism emerged as a modern salve to a modern problem, a countermodernity within modernity. Because late-modern Romantics like McQueen also find themselves caught between similar cross-pressures as their nineteenth-century forbearers, they too suspect there might be “something fuller, deeper,” and therefore, they also turn to the world-making power of the arts, explore the boundaries of humanity, and seek to find a fullness through encounters with nature.13

Taylor’s analysis sheds light on McQueen’s conflicted sketches of a miraculous, transformed, and beautiful body. Through his catwalks, McQueen reached into the depths of his imagination to hold out both a critique of constricting forces (e.g., consumerism, convention, racism) and a vision for a new world, a better humanity, a fuller or deeper something unleashed. Often, as in Plato’s Atlantis, McQueen sought this something through reimagining the body in light of an encounter with nature. Given the success of McQueen’s work, it appears he touched a powerful sentiment still at play: an impulse to imagine a body unleashed, transformed, and reclaimed to its fullness.

Yet as McQueen’s conflicted runways demonstrated, this vision is problematic within a secular frame. Taylor points out, as McQueen decried in his Voss show, that the task of choosing a lifestyle presents its own burden,14 and this burden is all the more pronounced in a secular age because such decisions are measured merely through social reference—for example, through the fashion media’s objectifying stares in the Voss show. Like the self-focused models in the Voss show, we are thus left without adequate resources to ground the fullness we seek. Therefore, the miraculous is problematized, transformation is seen as little more than illusion, and deeper beauty is crushed by cultural constriction. Accordingly, and again in line with Taylor’s analysis, late moderns are torn: fashioning the body has become critical for finding fullness, yet at the same time the experience is strangely elusive, a tease, oppressive.

This predicament suggests an uncanny resonance with St. Augustine’s famous claim: “Our hearts are restless until they find their rest in thee.”15 Indeed, McQueen’s work attests to the ongoing power of the aesthetic body to evoke powerful theological motifs on the post-Christian West, even as the fullness that such longings suggest is incommensurate with an immanent frame. Such is the dynamic behind the conflicted deferral one recognizes in McQueen’s work. This impulse is not to go unnoticed, for if we take Taylor’s claim seriously—that Romanticism emerged as an attempt to reclaim something lost in the absence of the Christian faith—then McQueen’s intimations of a miraculous, transformed, and beautiful body are nothing less than traces of the Christian vision of resurrection which continues to haunt both collective memory and common culture.

Death and Two Dantes

London Telegraph fashion director Hilary Alexander noted, “McQueen did not just look at clothes, he looked at the whole sway of the human landscape.”16 In line with this, in his fall/winter 1996/1997 Dante collection, McQueen positioned himself as a modern day Dante, trekking through the inferno of the modern world, seeking to articulate contemporary fears, juxtaposing and merging the modern quest with the anxieties of our contemporary context. Even so, a strong contrast exists between the medieval and modern Dante. Where the former respected death as deserving a passionate denunciation, the latter demonstrated “little humble sense of mortality.”17 And while one saw death defeated by a God who passed from death to resurrection, Inferno to Paradiso, the other merely toyed with death in what Rebecca Arnold sees as an act devoid of “moral restraint.”

McQueen’s Dante show began with backlit stained glass windows and a candle-lit, cross-shaped runway. As Victorian church music began to play, one might have sensed that this was the soundtrack to McQueen’s vision of salvation. But the models strutted on stage dressed like LA-gang-style youths, sporting images from Don McCullin’s iconic war photographs, and the church music was overpowered by the sound of gunfire and pounding club music. Caroline Evans sums up the message: “the collection was about religion as the cause of war throughout history.”18 Clearly missing (or rejecting?) the Christian hope of resurrection, McQueen found himself unable to offer anything substantial to take its place.

This gap is evident in McQueen’s Givenchy fall/winter 1999/2000 show. In the show, mannequins with translucent heads sprang up from trap doors, rotated slowly across the runway, and then descended back into the floor. Those present were amazed at the lifelike movement of the dummies. At the completion of the show, McQueen “rose up . . . like Mephistopheles to take his bow before descending back into darkness.”19 McQueen’s illusion of bridging the space between animate and inanimate bodies, between deathliness (the fall) and beautiful life (consummation) took place “behind the scenes.” For McQueen, such reversals remained a slight of hand.

Conclusion

In 2010, Alexander McQueen came face to face with death itself as revealed most horrifically in the death of his mother. Despairing in the face of such an enemy, he took his own life. McQueen’s death is lamentable on many levels. Considered the “genius of a generation,”20 his suicide represented not only the loss of a celebrated designer but a man who was keenly attuned to his age. Although this modern Dante’s journey was cut short, one can still retrace his moves through his catwalks. There we can see that even in an increasingly secular world, the news of a miraculous, transformed, and beautiful body that once jarred the first century and held the West’s imagination for over a millennium continues to echo. Yet tragically, like McQueen, many people have trouble recognizing the elusive body that haunted McQueen’s catwalks. Therefore, as we remember McQueen’s life, may we do so praying for those who, though now equipped with low-rise jeans, still await ears to hear and eyes to see the body’s true hope.21

1. McQueen’s work has been exhibited by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, Design Museum, Guggenheim, Victoria and Albert (London), and the Textile Museum. Additionally, McQueen’s work has been discussed by noted fashion theorists such as Carol Evans, Bradley Quinn, Elizabeth Wilson, Brenda Polan, Rebecca Arnold, Malcolm Bernard, and Valerie Steele.

2. Cf. 1 John 3:2.

3. Watt, The Life and Legacy of Alexander McQueen (New York, NY: Harper Design, 2012), 262.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid., 261.

6. Andrew Bolton, Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011), 197 and 142.

7. Evans, Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity and Deathliness (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 94.

8. Ibid., 98.

9. McQueen’s inspiration for this display was Joel Peter Witkin’s photograph “Sanitarium.”

10. Andrew Bolton is the costume curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See Bolton, Alexander McQueen, 12–15.

11. Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007), 3.

12. Taylor, A Secular Age, 304.

13. Ibid., 326, 358, 384, 353, and 403.

14. Svendsen, Fashion: A Philosophy (London, UK: Reaktion, 2006), 140–41; Taylor, A Secular Age, 482–84. And note here how styling a life is an aesthetic task.

15. St. Augustine, Confessions, trans. R. S. Pine-Cofin (New York, NY: Penguin, 1961), 1:1.

16. Alexander, “Alexander McQueen’s suspected suicide: Hilary Alexander’s tribute,” Telegraph, accessed June 4, 2010, http://www. telegraph.co.uk/fashion/fashionvideo/7216018/Alexander-McQueens-suspected-suicide-Hilary-Alexanders-tribute.html.

17. Dante Alighieri’s poem declares, “Death, always cruel, Pity’s foe in chief / Mother who brought forth grief / Merciless judgment and without appeal! / Since thou alone hast made my heart to feel / This sadness and unweal / My tongue upbraideth thee without relief.” Later, Dante explains, “I address Death by certain proper names of hers . . . I tell the reason why I am moved to denounce her . . . I rail against her.” See La Vita Nuova, trans. Gabriel Rossetti (Toronto, Canada: Dover Publications, 2001), 7. In contrast, see Rebecca Arnold, Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: Image and Morality in the 20th Century (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001), 59 and 59.

18. Evans, Fashion at the Edge, 157. In spite of his references to Darwin in many of his shows, McQueen was not a materialist. Nearly nine years later, when McQueen’s close friend Isabel Blow committed suicide, he spent a month in India on what he called a pilgrimage, immersing himself in “the contemplative life and Buddhist culture.” See Bridget Foley, “Hail McQueen,” W Magazine, http://www. wmagazine.com/fashion/ 2008/06/alexander_mcqueen?currentPage=1.

19. Ibid., 89.

20. Kristin Knox, Alexander McQueen: Genius of a Generation (London, UK: A & C Black, 2010), 7.

21. See Ezekiel 12:2.