Sunday

We are on the boat, our family, barreling north into a sea of granite peaks. Before us spreads the gleaming surface of Lake Chelan, a fifty-one-mile gash cutting deep into the Cascade Mountains. To our right, the eastern foothills flow by, sun-browned in the August heat. They lie hulking like knuckles on a fist.

In my lap a sudden movement. Samuel, my son of two months, raises his own tiny fists to the sky. He arches his back, stretches his legs, and scrunches his face. His skin flushes to red. “Rrngfthgh,” he explains. It’s one of his daily grunting sessions—not a bowel movement but a release of some wordless tension only he can fathom. I jounce him in my arm and he stays asleep.

Beside me, my wife, Hannah, watches Sam and returns to her book. We are riding a one-hundred-foot ferry propelled by thrumming diesel engines. We are bound for Holden Village, a Lutheran retreat on the site of an abandoned copper mine. To reach Holden is a full day’s journey from almost anywhere. First by road, then four hours on the ferry, then a school-bus ride up a valley. I have never been to Holden, but I’ve been dreaming about it for years. People describe it, their eyes lighting up, as an intentional community deep in the Cascades that welcomes short-term and long-term visitors alike to work or rest. With Hannah and I both on family leave from our jobs, we decided it was time for the journey, even if Sam makes travel complicated.

We’ll both be back to work all too soon, and we feel a need to reflect—on our new roles as parents, our marriage, and how we might attune ourselves to the places we inhabit, whether that’s a dramatic mountain refuge or our neighborhood in Seattle. We hear that Holden is a place of reflection, a place without TVs, advertisements, and the Internet. Plus, they have a diaper-washing service.

I rub the belly of the grunting boy in my lap, hoping to soothe him. Hannah nudges me and motions to the snow peaks coming into view up the lake. Chelan is the third-deepest body of water in the United States, after Crater Lake and Tahoe. Its bottom sits below sea level. I try to focus on a book, then turn again to the mountains gliding by. Sam cries and I offer his pacifier, which he sucks at hungrily. I reach for my coffee mug and reopen the book to find my place. Then a voice blares on the loudspeaker, telling us we’re approaching the landing dock.

This rapid switching from task to task feels like channel surfing. I’m hoping Holden offers a break from this frantic pace. I’m hoping to give sustained attention to fewer things—reading, writing, conversation, exploring the land around us. We’ll see what Sam thinks of the plan.

We board one of Holden’s well-loved yellow school buses and climb the gravel switchbacks to the village. The rumbling and bouncing suit Sam just fine. Stepping off the bus, I see only forest until I look higher and find dramatic granite peaks looming impossibly close to us. In winter, the village spends whole months in shadow, the sun never climbing above the southern ridgeline. Around us are a dozen alpine-style lodges and chalets built with solid timber. These structures, originally constructed by miners, were built to last. And it’s clear the Lutherans have tended them well since taking over fifty years ago.

At lunch in the dining hall, we fill our plates with salad greens and fresh bread—a typically modest but satisfying Holden meal. Afterward, Hannah and I both want naps, but Sam won’t allow it, so I carry him on a walk. We wander the village, visiting the library, pottery room, hiking shed, and fishing supplies. It’ll be tempting to pack my week with too much activity. It always is. We walk along the creek that divides the valley, looking for fish. The water clatters and chatters and Sam relaxes with the noise.

You’re free at Holden to be a Lutheran or not (we’re not), to believe in God or not, whatever. They welcome everyone. But the staff invites everyone to attend a nightly worship service as part of the communal life of the village. So Sunday night we head to Eucharist, the longest service of the week. We gather in the reconfigured gymnasium, and I thumb through a daunting twenty-page order of worship. I’m not well versed in Lutheran theology, but I figure if they’re hosting us in a paradise like this we can hear them out for an hour.

Except that it’s past Sam’s bedtime and we’re all exhausted. The choral singing calms him, but when it’s finally time for communion, I’m mainly thinking about getting him back to our room. The minister speaks words of preparation for the bread and wine, and the cantor sings. We line up to approach the front, Hannah carrying our sleeping child, his legs dangling, his feet not quite reaching the ends of his blue pajama legs. We reach the officiant, a volunteer in sandals and gym shorts. He tears bread from the loaf and hands it to Hannah: “The body of Christ, broken for you.”

Hannah is about to move down the line, but then the man places a hand on Sam. He bows his head and whispers. I watch his lips move, not hearing what he says, and my heart swells at the sight of this stranger blessing my son. This child can’t provide anything for himself, can’t even find his hands to suck; he relies on us for everything. Just as his needs are my responsibility, somehow his blessings are mine as well. I accept the bread, then drink from the cup of rich red wine, from the Columbia River Valley downstream from here. We carry Sam to the room, lay him down, and take our rest.

Monday

At breakfast we enter the dining hall just as the last of the mine workers are leaving. The mines closed after World War II when the price of copper crashed. The multinational Rio Tinto corporation has recently agreed to finance an extensive cleanup that will channel away water from the remaining tailings, protecting downstream water sources. It’s an elaborate process, involving some fifty workers from eight contractors who are sharing the village with staff and guests. They eat breakfast before us, depart for twelve-hour workdays, and return to eat dinner after us. The entire valley south of the creek is closed to the public for the next three years. Most of the work is out of sight, but we hear the rumble and groaning of machinery through the forest.

I don’t fully understand the remediation project, but it seems to be a sign of success that Rio Tinto is restoring the damages of a subsidiary it long ago acquired rather than evading responsibility. Holden long-timers seem happy with the presence of the miners, whose presence will change the character of the village for several years.

Last night at the worship service, the village pastor said, “One of my favorite questions is to ask people why they are at Holden.”

I’ve been coming here every summer for thirty-five years.

I’ve gotten up here once every decade, and it lets me mark where I’ve come in life.

I just retired and I want to reflect on what I’ll do next.

I got divorced six months ago and I just need to rest.

I don’t believe in God, but I believe in community. I believe in the peace of mountains.

I work for Rio Tinto—I’d never heard of Holden.

That got me thinking about why I’m here. I turned thirty this summer and six days later became a father. I’d like to enter this new role with a calm, centered mind. But I’m learning it’s not really a job for the mind. This child in our care doesn’t ask me to ruminate on life’s stages. He asks for clothing, bathing, holding, jouncing, diaper changing (and changing and changing), swaddling, making funny faces, and bringing him to Hannah to feed. His birth and his care require constant washing of bottles and pacifiers, nights of broken sleep, and supporting Hannah as much as I can. Whatever my ponderous mind can bring to the job, willing hands and tender words are more important. In the village laundry, where we drop off dirty diapers, there is a Richard Wilbur poem on the wall with the title “Love Calls Us to the Things of This World.” That phrase seems just right.

Tuesday

Today I leave Hannah and Sam in the village to hike with Nathan, another father I’ve met from Seattle. We head northwest up the valley along Railroad Creek, named by the white settlers who charted the valley in search of a railroad passage to the Pacific. Conversation flows easy and the climb goes fast. Soon the fir and pine forest thins and we stop to take in views. Forest blankets the valley below except for clearings of orange soil where heavy trucks work. Great rolling sheets of clouds drift in, keeping us cool and comfortable. We can see them break apart as they reach the warm air east of the mountains.

Soon we finish the switchbacks and climb a meadow trail to Holden Lake. Gray shaggy marmots dart out of sight, if a fat waddling creature can dart. They must be bulking up before winter. Grazing deer look up lazily. That’s probably a sign there are no bears around. Finally the lake appears, an emerald teardrop lying before a granite boulder slope. After a stop for trail mix, we follow a narrow trail that skirts the lake before disappearing in a tangle of young willows. They have stiff, low branches, and bushwhacking here is awkward, slow, and painful. Eventually we reach a boulder field and put our hands to work along with our feet. Half the rocks wobble upon landing, and each footfall becomes a guess. It is slow going. Conversation halts as we focus on each movement. My mind is too occupied even to daydream. My heart labors to keep up. A friend who does technical mountaineering says he loves this process because it requires a mind fully in the present. There’s no room for thinking about anything else. Find the next foothold, make sure the boulder doesn’t move, then look for the next. Step. Step. Step. It’s nothing too complicated, yet it requires absolute focus.

Finally a saddle comes into view, swooping down from the ridge peaks, and with a final push we are at the pass. Ahead of us lies a new valley, barren slopes falling into green meadows and then to forest. Lunchtime. We unlace our boots and open our packs. We talk about other trails we’ve hiked. I love climbs like this for bringing me into the present, yet I find I carried away plotting future trips, pining for long stretches in the wilderness. That’ll be even tougher now with Sam. It may be years before our family is able to take overnight backpacking trips. We tear through our peanut-butter sandwiches from our spot straddled between wild valleys, streams falling thousands of feet in two direction, snowmelt in each one tumbling for unseen miles before meeting in Lake Chelan.

Wednesday

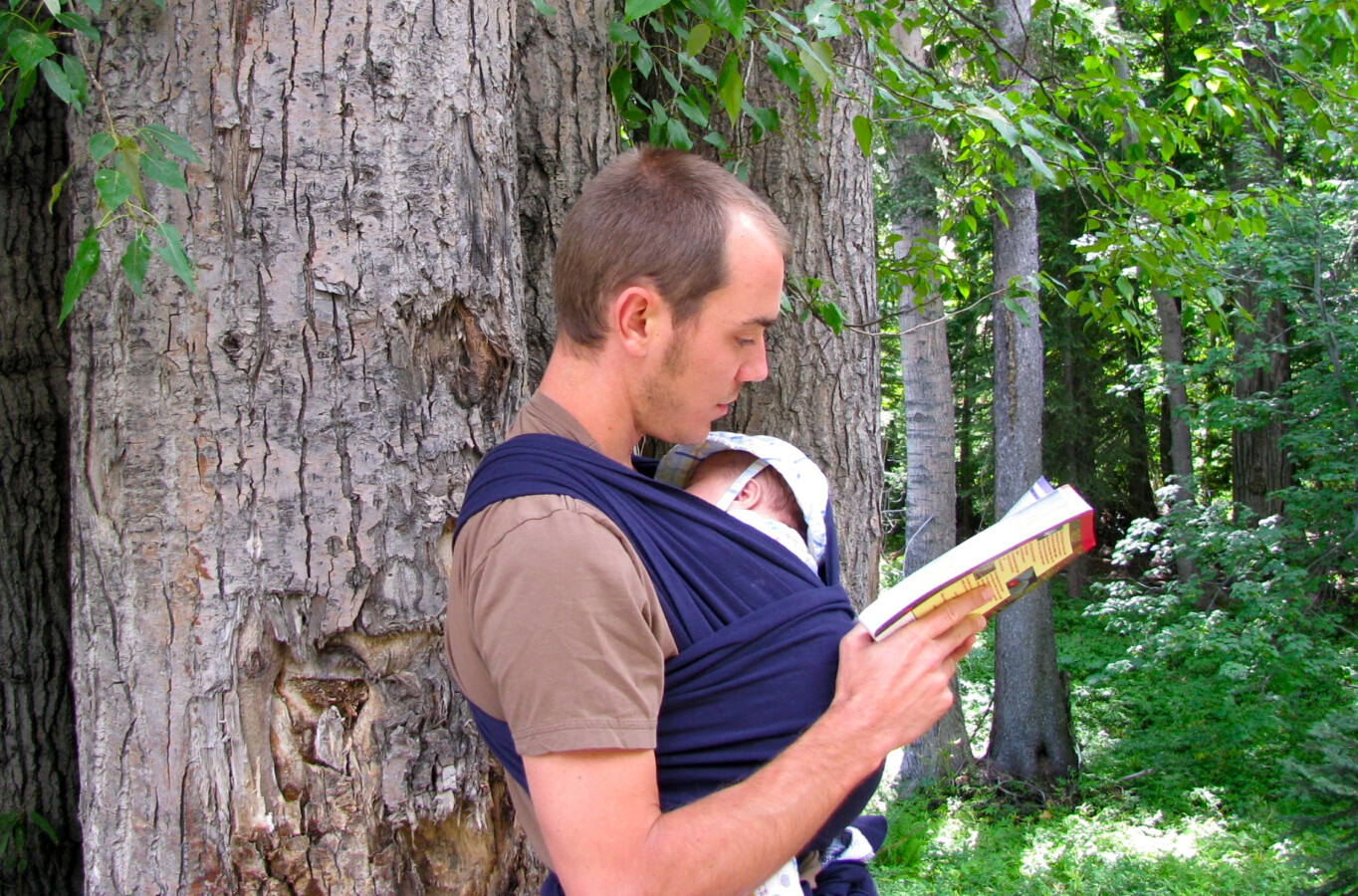

Today Hannah and I stay near the village and walk a short creekside trail. I’m carrying Jim Pojar and Andy MacKinnon’s Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast, a field book that’s colorful and comprehensive yet so heavy I rarely take it hiking. Sam dangles from his carrier on my chest, looking over my shoulder. With his eyesight still developing, the trees must be blurry green shadows, the mountains gray nothings beyond his vision.

When we were dating, Hannah sent me a letter with a poem from Gary Snyder. It ends with a trio of commands:

stay together

learn the flowers

go light

I hear a personal charge in Snyder’s call to learn the flowers. I’ve been intending to study native plants since we moved to the Pacific Northwest four years ago. Once I began to grasp their boundless complexity, learning to name a few seemed like the only decent response. Many of the writers I most admire—Henry David Thoreau, Annie Dillard, David James Duncan, Scott Russell Sanders—fill their work with the flora and fauna of particular places. But it’s difficult. Before long I get distracted and despair of keeping firs straight from spruces (and there are five types of firs in the field guide). And that’s just the trees. I’m even more hopeless with flowers, shrubs, mosses, lichens, and birds.

Today we learn to identify cottonwood trees, spotting one near the hiking shed. Deep craggy furrows cover its bark, and its trunk rises out of sight. Its glossy heart-shaped leaves flutter in the valley breeze. I notice more cottonwoods shimmering up and down the valley. From the guidebook I learn that the Chehalis tribe considered cottonwood to have a life of its own because it shakes even without a discernible breeze. I learn that the Nuxalk tribe used gum from cottonwood buds as a remedy for sore throats, whooping cough, tuberculosis, and baldness. The Okanagan made soap and hair washes from cottonwood ashes. The Squaxin considered it an antiseptic plant and placed bruised leaves on cuts. They drank a bark infusion for sore throats.

That’s maybe half the information on the black cottonwood (Populus balsamifera ssp. trichocarpa), one of 794 species listed in the field book. Perhaps that’s why I get discouraged: once you begin learning about plants, there’s no finishing. Maybe I can make it a lifelong project, learn a little every year. But there’s more urgency now with Sam. I want to be able to teach him the wildflowers. My parents didn’t teach me much about wild creatures, but they taught me about humans—that people more than anything want to be heard; that listening and humor are chronically underrated; that beneath the most bizarre behaviors lurk the same basic motives we all share. They taught me that people are infinitely complex, finely differentiated, worthy of patient study. There’s no end to the learning.

After dinner I read in bed and bounce Sam in my arm. Normally he calms down with jostling and his pacifier. Not this time. I was lost in my book and hadn’t noticed he’d been crying for several minutes.

“Give him to me,” Hannah says. There’s an edge in her voice and in her eyes. She calms him down, and a short while later I apologize. We both realize that we’re tired. We need all the breaks we can get here. When a fellow guest offers to hold Sam after vespers while we get ice cream, we gladly accept.

Thursday

Hannah heard rustling in the brush before we saw the bear, so we were making noise and ready to react when we rounded a bend and came upon the shaggy dark creature snuffling and rooting maybe fifteen feet from us. Sam hung from his wrap on my chest, asleep. His first hike, his first bear encounter. We quickly made ourselves loud and backed the hell up. The bear kept snuffling, never raising its head.

We had hiked with a group out to Hart Lake, some four miles up the valley. It was Hannah’s first hike since the birth, and a bit longer than we might have chosen, but the trail followed a gentle slope, shaded by the creekside forest most of the way. I wrapped Sam on my front and carried a backpack with enough clothes, diapers, and changing gear for five or six babies. We’re still learning. Hannah carried our lunches. We left with a handful of adults and three or four kids and agreed to turn back early if eight miles proved too much.

With good conversation and amped-up kids setting the pace, the outward trip went quickly. I practiced my newfound ability to identify cottonwoods (or are those aspen?) and Sam slept in his snug womblike pouch. At the lake, a sparkling turquoise mirror every bit worth the journey, we lunched on cheese and tomato sandwiches. Our group spread out from there, with some folks going a bit further and others staying to swim. It was just the three of us when we met the bear.

If I’m ever attacked by a bear, I really hope it’s not when I’ve got my son strapped to my chest—even my back would be better; I could shield him that way. After backing up, we stood thirty or forty yards from where we spotted the bear, watching the thick undergrowth for movement. We’d heard that the miners disturbed a mother and cub’s den with their excavation work, sending the pair up-valley looking for safety. I picked up two fist-sized rocks to bang together and throw if need be. We waited for the hikers behind us, two adults and three girls of age ten or so, whom we had recently passed. When they arrived, we decided to make a racket and try passing through. I tucked Sam’s head more firmly in place. If I had to move fast, I wanted him secure.

We yelled and banged rocks. Sam didn’t like his new position and contributed cries. Our yelling trailed off as we reached the spot, and I turned to the girls: “Hey, how many kinds of candy can you name?” A lot, it turned out. “Airheads!” “Warheads!” “Jawbreakers!” “Jolly Ranchers!” We hollered into the brush, walking slow and scanning for movement. “Snickers!” “Milky Way!” “ “Dark chocolate!” “White chocolate!” “Gross!”

I don’t know how I wound up in the lead again, with Sam in front, but for that stretch I led our train through the wilderness. The bear never reappeared. We yelled a while longer, but mostly because it was fun. It struck me as a fitting image of our family: at the moment we’re safe, even if we don’t know what threats lurk in the shadows. We know we can’t fight off all of them. But we’ve got good companions and a shimmering green valley to explore. And for once I’m remembering to enjoy it, to notice how a sunlit pine forest smells different than a rainy one, to watch the broken light filter through branches, reaching us way down here.

Friday

Today is a time for winding down, preparing for tomorrow’s departure. Other villagers inevitably start asking whether we’d come back, and while I think we’d both love to, we know it may be years until we do. Like most Americans, we don’t get much vacation time, and we’ll need to use what we have to let Sam get to know our extended family in the Midwest. This week I’ve been reading Jonathan Franzen’s novel Freedom, which probes the American notion of “have it your way” freedom—the myth that independence means merely the ability to chase your own desires. Make this kind of consumerist autonomy your highest goal and you’ll be miserable, Franzen seems to be suggesting. You’ve got to devote your life to something larger than yourself.

I think about this as I hike alone, something that feels selfish and a little unsafe. I asked Hannah to watch Sam again and told her I wouldn’t be too long. Some new friends and their children started the hike with me, but they wanted to turn back sooner than I did. I’d gotten it into my head that I could reach the end of a trail; I’d caught summit fever. I huffed up the steep incline trying to make good time. For what purpose? I realized before long that I’d rather be back with my family on our last afternoon here. Yet I also wanted to complete this self-imposed task. When so much of my work in life is murky and uncertain, I relish the clear accomplishment of a hiking goal. The destination is literal, not ambiguous. Yet even now I realize that my goal is arbitrary, that it’s not what’s best for my family or me.

I turn around at the campground at the end of the trail, underwhelmed and unable to enjoy the destination. On the way down I run wherever the trail is clear enough, eager to get back to my family. I’m still learning.

At dinner we sit with three teenage sisters from Michigan whose family has been playing extraordinary string music at vespers each evening. Over plates of salmon, rice, and greens, they talk about performing as a family quintet. I mention that the older two sisters, the violinists, exchange a lot of meaningful glances as they play.

The oldest sister smiles. “It usually means one of us made a mistake.”

Maybe so, but I admire the way they hold a full conversation through arched eyebrows and knowing smiles—all while playing heart-stirring hymns and folk melodies. It gives me hope for our family. We’re constantly missing cues and misunderstanding Sam’s cries, but in time we’ll learn to understand each other’s rhythms.

Saturday

We’re back at the landing on Lake Chelan, waiting on a long stone bench as waves slosh against the bank. The yellow bus has brought down those leaving Holden today, perhaps twenty of us. The ferry is late, so we’re lined up like ants on the shore of this vast lake. Dragonflies buzz overhead. Across the water the knuckled hills bake in the sun. I’ve just fed Sam a bottle, and now he sleeps in Hannah’s arms, beneath a swaddling cloth that shields him from the sun.

I’m glad for the delay that gives us time to sit and think about traveling back into the wired world. Beside Hannah and Sam sits the family of musicians from Michigan. The sisters all have notebooks open on their laps, writing down who-knows-what, their blond hair bright in the sun.

I’m reminded that this journal in my own lap is nothing unique. At Holden there were plenty of guests resting in Adirondack chairs with open notebooks, jotting down lines and gazing off at mountain peaks to think. I’m part of an endless crowd of journalers, letter writers, bloggers, tree carvers, and cave painters who want to leave a mark of what they’ve seen and felt. That’s fine. I still want a record of these early days of fatherhood. Taking notes has reminded me to notice what I feel and think and, more importantly, what’s happening around me. It’s helped me pay attention. The word journal comes from the French word jour—day. So often I’m apt to worry about the future or wallow in nostalgia. The practice of journaling pulls me into the present, where I belong.

And where my son lives.

Our bus driver cheers, and the rest of us look up. Miles up the lake, barely a speck on the horizon, the white boat appears, cruising south. We’re headed home.