When it comes to suffering, geography matters.[1] Where we live determines how we suffer and how we respond to that suffering, how we search for healing and hope. It is unsurprising, therefore, that the collective suffering wrought by colonization has molded indigenous theologies toward a hermeneutic of liberation. In many ways, African women’s theology arose as a direct response to the architects of the colonial project and their rogue, destructive ways of misinterpreting the biblical text; harm shaped a hermeneutics of liberation as resistance against the colonial powers and, more recently, against the economic exploitation and cultural hegemony of neocolonialism.

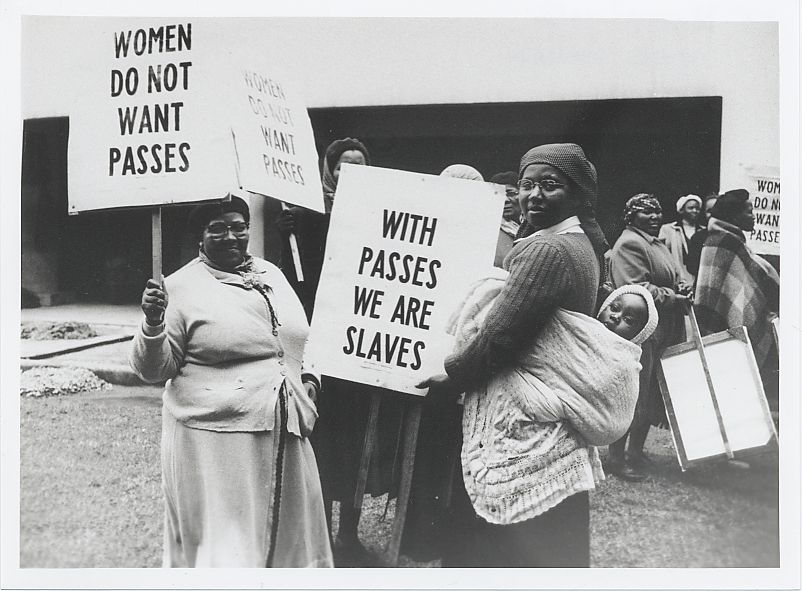

The marginalization of indigenous peoples, so characteristic of the colonial project and its scramble for Africa, resulted in the decomposition of entire African societies—politically, socially, religiously, economically, and culturally. Generally speaking, the colonists espoused a hermeneutic that was rooted in their desire for political control and economic gain. In South Africa we see a clear example of how such a hermeneutic institutionalized racial discrimination that, through apartheid, marginalized black and mixed race populations. Apartheid was intimately linked to the Christian faith and backed by the leaders of the church; the Dutch Reformed Church was one of the major institutions that assisted the South African government in installing its discriminatory and violent policies. The white Afrikaner leaders who instituted apartheid revered Old Testament stories that reinforced their status as chosen people, such as the story of Moses leading the Israelites to the promised land. They held themselves to be modern-day Israelites and South Africa to be their land overflowing with milk and honey. They believed that God had given them and their descendants the whole of South Africa as their promised land. They were captive to a sense of manifest destiny and nothing would impede their right to inhabit the land that had been divinely provided as their own.

The legacy of the apartheid hermeneutic is seen in the social, racial, and gender inequalities that permeate the South African cultural landscape today. Nowhere is this legacy more acute than in the health-care system, where ideology carried over from the apartheid era continues to cause disparities along racial lines: infant mortality is nearly ten times higher in the black population than in the white population; there is one physician per every 330 whites versus one per every 91,000 blacks; and life expectancy is 55 for blacks and 70 for whites.[2] South Africa has one of the highest HIV/AIDS rates of any country, and its highest burden is borne by blacks. As the pandemic has swept through the nation, systemic issues of gender inequality and race-related poverty have stymied effective prevention and treatment efforts. HIV/AIDS is a gendered, geographical disease; although it infects and affects men and women all over the world, its heaviest burden falls on women in sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of global HIV/AIDS cases occur. These women are viewed as less than full citizens or even full human beings, and this dehumanizing perspective has translated into sexual exploitation and epidemic levels of rape, which further exacerbates the high infection rates. Young women in South Africa are five times more likely to be infected with the HIV virus than are young men.

A biblical hermeneutic that engages the sacred text through a lens for liberation and healing from the ravages of AIDS must, then, bear witness to the injustice of gender inequality and economic poverty. The Botswanan theologian Musa Dube speaks with just the prophetic voice to address this issue. Much of her work focuses on gender- and HIV/AIDS-sensitive rereadings of the biblical text through which she tactfully reproves the injurious hermeneutics imposed by imperial Christianity. She asserts that the suffering of African women today has been made worse by reading the biblical text in a way that connects disease and poverty with God’s punishment, portraying women, children, homosexuals, and displaced persons as the targets of God’s wrath.[3] Dismantling such a detrimental hermeneutic, which the architects of imperialism so steadfastly crafted, has become one way in which Dube has resisted the persistent yet covert forms of colonization and persecution that remain deeply entrenched in her context.

Dube writes that female leaders in sub-Saharan Africa are embracing “justice-seeking ways of reading [the biblical text] that affirm life, the right to healing and medicine, the human rights of all, while they counteract the social structures of poverty, gender, and international injustice, which are the fertile grounds for the spread of HIV/AIDS.”[4] By bearing witness to the suffering and structural subjugation of African women while also calling forth embodied justice and a movement toward life, Dube and her fellow African theologians are attempting to undermine systemic and societal evil, counter the spread of HIV/AIDS, and act as a catalyst for the gospel.

For an example of Dube’s postcolonial feminist theological paradigm consider her rereading of Mark 5:21–43. This narrative tells of the woman who had been suffering with a bleeding disorder for twelve years and could not find relief. When Jesus passes by, she reaches out in faith and touches his cloak, which results in a miraculous healing. Jesus then accompanies a man named Jairus to his home, where his daughter lies dead as a result of an illness. Jesus speaks, calling the girl to rise up, and she is made well. A traditional (and valid) interpretation of this text points the reader to broad categories such as the importance of having faith and belief amid suffering. However, Dube focuses on the nuances of the narrative that become apparent only when read from a different worldview—in her case, one that is rooted in the oppression that African women encounter daily.

Dube retells this story of the bleeding woman and the dead girl as Africa’s own story, the narrative of suffering women across the continent and their encounters with the powers of oppression. When Jesus enters the house of Jairus and sees the girl’s limp, lifeless body lying there before him—a symbol, Dube argues, of wounded Israel being pressed down by the heavy hand of Roman imperial rule—he speaks words that bring life back into her: talitha cum, rise up. These words catalyze life, healing, and liberation. A foundational story for women in this context, it is fitting that the name talitha cum theologies has been adopted by African women’s theology. According to Dube, talitha cum is “the art of living in the resurrection space . . . continually rising against the powers of death—the powers of patriarchy, the powers of oppression and exploitation, the powers that produce and perpetuate poverty, disease and all forms of exclusion and dehumanization.”[5] This is a space pregnant with the possibility of witnessing life rising out of death; it is here that African women’s theology is manifest in the stark realities of daily existence on the continent.

Another poignant example of Dube’s reinterpretation of the biblical text through a lens of liberation is seen in her reading of the story of the demoniac in Mark 5. Jesus approaches a demon-possessed man who had been living among the tombs of a burial ground. Upon seeing Jesus, the man pleads to be left alone. Jesus responds by asking what his name is, to which he replies, “Legion.” Jesus then proceeds to cast a demon out of the man and into the swine standing nearby. The political and social undertones of this story are apparent in several ways. At the time, legion was a term used for a battalion of Roman soldiers. The demon-possessed man, then, is portrayed as having been occupied by Roman imperial powers. Dube suggests that this narrative is a creative articulation by its author, demonstrating in a subversive way that colonization bears the quality and likeness of demon possession; to be colonized is to be possessed by an evil spirit. The Roman occupation created a geopolitical context, she says, that led to a human being residing in a tomb, annihilated by the evil imperial forces and living among the dead in a subhuman way. In casting the spirit of Legion into the swine, Jesus was, in effect, casting out the spirit of Rome and its powers of subjugation and death.[6] The response of Jesus in this situation bears witness to the radical subversion of empire that he stood for. Here, he is seen as one who liberates, bringing healing into a space of unbridled iniquity and darkness. For Dube and other African women theologians, this is the Jesus of Africa who is the catalyst for life where death once ruled as king.

With a prophetic voice similar to that of Dube, Mercy Oduyoye looks at African women’s theology through a contextual Christology. According to her perspective, Christology must be about how women live into the liberation of Christ in an active, participatory manner. Theology for the African woman is an embodied reality that presses against all the powers that seek to dehumanize—the powers of patriarchy, racism, poverty, and disease—while simultaneously welcoming a spirituality that advocates for the liberation of her humanity.[7]

The African Instituted Churches is a postcolonial institution that seeks to provide an alternative to the colonial style of Christianity that has dominated the landscape for so many decades; it is a network of churches in which African women are able to participate in Christ’s liberation. Here, women have been afforded the opportunity to revisit their core identities as they relate to religion and to read their own lives as contextualized by Jesus’s story.[8] In their embrace of a movement that expresses a spirituality of liberation rather than a Western missionary religion, African women have found in Jesus one who suffers with and for them. In his victory over death, they find hope and a reason to move forward into the experience of resurrection in their own lives. Oduyoye presents a theology of the African woman that is holistic in scope, like that of Dube, with a lens for liberation from disease, sexism, racism, poverty, and patriarchy.

Liberation in this sense is so intricately tied to salvation that the two become inseparable.[9] A contextual approach to theology, one that recognizes the role of place and history and culture, brings with it a contextual approach to soteriology, and in the case of African women this now means a propitious and concrete shift away from bondage and into freedom. This is an embodied and present salvation, one that will neither be postponed nor replaced by the hope of an ethereal afterlife. The cross is now—and so is resurrection.

[1] In this essay, I write about female theologians from sub-Saharan Africa from the perspective of a white, North American male. I acknowledge the inherent complexities of this endeavor. Also, note that this opening line is adapted from the opening sentence of Kris Rocke and Joel Van Dyke’s Geography of Grace: Doing Theology from Below (Tacoma, WA: Street Psalms, 2012), 17, which reads, “When it comes to grace, geography matters.”

[2] Victoria Scrubb, “Political Systems and Health Inequity: Connecting Apartheid Policies to the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in South Africa,” The Journal of Global Health 1, no. 1 (2011): 7.

[3] Dube, “Grant Me Justice: Towards Gender-Sensitive Multi-Sectoral HIV/AIDS Readings of the Bible,” in Grant Me Justice: HIV/AIDS and Gender Readings of the Bible, eds. Musa Dube and Musimbi Kanyoro (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004), 6.

[4] Ibid., 13.

[5] See Dube, “Talitha Cum: A Postcolonial Feminist and HIV/AIDS Reading of Mark 5:21–43,” in Grant Me Justice, 134; and Dube, “Talitha Cum Hermeneutics of Liberation: Some African Women’s Ways of Reading the Bible,” in The Bible and the Hermeneutics of Liberation, eds. Alejandro F. Botta and Pablo R. Andinach (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2009), 138.

[6] Ibid., 125.

[7] Oduyoye, “On Being Human: A Religious Anthropology,” in Introducing African Women’s Theology, eds. Mary Grey, Lisa Isherwood, Catherine Norris, and Janet Wooton (Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2001), 73.

[8] Oduyoye, “Jesus the Divine—Human: Christology,” in Introducing African Women’s Theology, 55.

[9] Ibid., 64.