Horror films have mastered the formula of fright. They draw the viewer into a world that looks and feels somewhat familiar: we see houses that look like our houses, we see people that look like us. Yet, in spite of the familiar, we know. We know the house is not empty. We anticipate the stranger in the dark. The audience in the theater acts as one: muscles contracting, eyes squinting, shoulders pulled up as if to lessen the impact of what we know is about to happen. We wait.

I am one in an audience of two hundred packed into a theater in Park City, Utah. We are strangers participating together in the Sundance Film Festival. The theater is cold and dark. I close my eyes and turn my head to the side. The film is so grotesque, the story so vivid and terrible that my body involuntarily tries to stop what is coming at me.

There is no blood. No one is lurking, dying, or trying to escape. There is only a woman. She is alone on the screen and she is telling her story. It’s a true story. I am watching a documentary: I am watching [1]

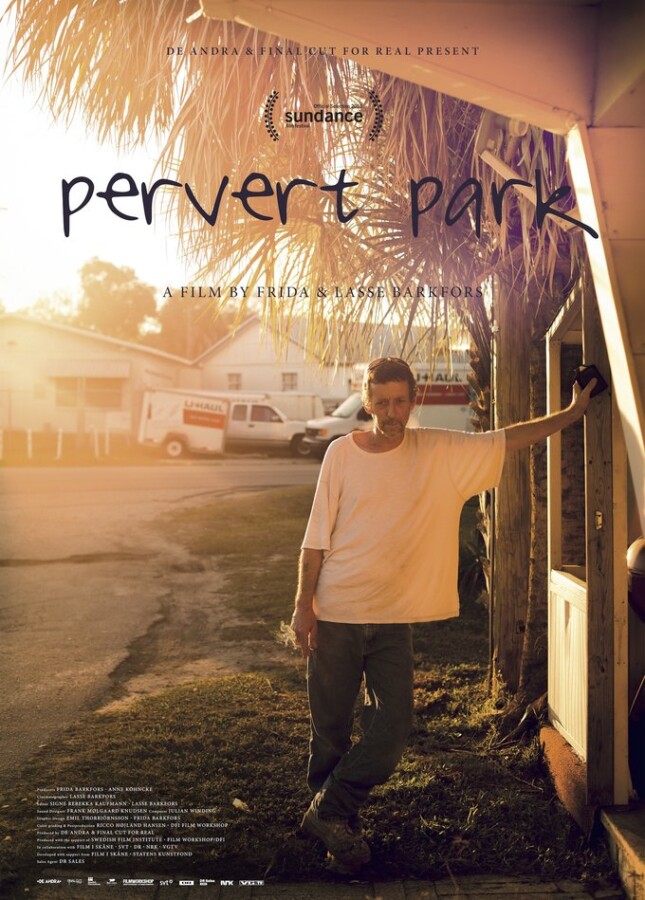

Pervert Park is a pejorative name often used to describe the Florida Justice Transitions center, a community of one hundred twenty convicted sex offenders living together in a trailer park in St. Petersburg, Florida. Florida laws stipulate that sex offenders are not allowed to live within one thousand feet of places frequented by children, such as schools, playgrounds, and churches. To ensure offenders abide by this law they must register their residential address once every two years and alert neighbors of their status as convicted sex offenders. These regulations, combined with the difficulty of finding employment and a subsequent income, leave few places for offenders to live. The Florida Justice Transitions center was established by Nancy Morais, whose son struggled to reintegrate into society and find a place to live after his conviction.

Many residents of the Transitions community find employment within the trailer park through maintenance and repair jobs. The staff members, some of whom are offenders themselves, provide mentoring, job placement, and legal compliance assistance, as many of the residents are required to wear monitoring devices and maintain strict records of their locations. Pervert Park acknowledges these aspects of community living, but the central focus of the film is on how residents pass the days, sharing meals, watching television, talking, participating in church services, and attending group counseling sessions with Don Sweeney. Earlier in his career, Sweeney counseled victims of sex crimes. It was through his work with these victims that he was asked, often by the victims themselves, to provide counseling to perpetrators. In the Florida Transitions community, Sweeney works to create a safe, open environment where residents can share freely about their struggles and successes: without judgment, without shame.

Pervert Park tells the stories of its residents by depicting one-on-one interviews with the filmmakers, group counseling sessions led by Sweeney, and the mundane tasks that comprise daily life. The Danish husband-and-wife team Frida and Lasse Barkfors shot this documentary, their first, in an attempt to expose stories that are often too painful and too uncomfortable to discuss. By creating an atmosphere of trust, they sought to give the most despised humans a platform to speak openly about their crimes, their recovery, and ultimately their humanity.

Like many documentaries, Pervert Park asks us to look at something we would rather not see. It directs our attention to the humanity of those we might otherwise shun. It gives us the opportunity to consider not only the crime but also the criminal whose life existed both before and after the crime. Though it is difficult to watch and painful to process, Pervert Park is in this way a film that can teach us how to see.

I want to be very clear here: Pervert Park does not attempt to rationalize or dismiss the crimes committed by the offenders. It is not a film about forgiveness. It is not a film about the victims. Instead, it is a film about Bill, Tracy, Jamie, and Patrick, four residents of the Transitions community whose stories unfold in a non-linear way.

When we are first introduced to these residents, we see a sort of purgatory where the residents are neither prison inmates nor fully integrated members of society. The visual structure of the film underscores this storytelling technique by literally following the residents as they walk the empty streets of the mobile-home park. This is not a neighborhood in the traditional sense: there is no through traffic or idle passersby, no children and few pets. We follow in the steps of the residents and it is from this vantage that we are given eyes to see the lives of people we, most of the time, would rather not see.

We meet Bill. He is tall and skinny with gray hair and sad eyes. He works maintenance at the center, installing showers and preparing trailers for new residents. We learn that from a young age Bill and his brother were sexually abused by their babysitter. Bill speaks plainly about the abuse he endured from his babysitter, as well as the physical and emotional abuse he suffered from his parents. He was forced out of his home as a teenager. He fell in love, married a young woman, and began a family of his own. A tragic traffic accident took the lives of Bill’s young family and sent him, as he describes it, in a downward spiral that eventually landed him in prison as a sex offender.

It is unclear how long Bill has been a resident at the park. What is clear, though, is that Bill has become an advocate for the program and the humanization of its residents. The Florida Transitions center has a 0 percent recidivism rate, which means that they have never had a resident reoffend. Bill wants people on the outside (as he calls it) to know that with the proper help and support, the lives of sex offenders can be changed for good.

We meet Tracy. She takes classes and sings for the church service. She is overweight, has short red hair and deep lines around her bright eyes. Tracy was in prison for sexually abusing her eight-year-old son. Her history with abuse began when her father molested her while she was still a baby in the crib. She was sexually active her entire childhood and received, unbeknownst to her at the time, an abortion before she was even a teenager. Tracy’s shattered trust and misguided introduction to sexuality led her to an ongoing intimate relationship as an adult with her own father.

Tracy claims responsibility for her crimes as a victimizer like no one else in the film. In a poignant scene, we witness a group counseling session where residents discuss the difficulties of having outsiders hold such a permanent, negative opinion of the residents of the community. They see us as monsters, Tracy says. When Sweeney asks if she sees any monsters in the group, Tracy, without missing a beat, replies, “No, just me.”

We meet Patrick. A socially isolated gamer who raped a five-year-old girl. He admits that he will never leave the Florida Transitions center for fear that he might relapse and offend again.

We meet Jamie. A graduate student who was caught in an online sting operation for agreeing to have sex with a minor. He hopes to become a professor and teach film studies.

These are the stories we hear when we are willing to listen. They are quite literally the stories of the least, the last, and the lost. They are ugly and heartbreaking, gritty and real. The Barkfors’ documentary gives us eyes to see complexity in a world so often depicted as one-dimensional. But to reveal dimension comes at a price, to stand inside this complexity puts us in a vulnerable position.

After the film ended, some audience members filed out of the room while others remained seated for the question-and-answer session with the filmmakers. The atmosphere was tense and solemn. In place of the chatter that typically follows screenings at Sundance, there were only hushed whispers. When the lights came back on, I found that I could not move from my seat. What I had witnessed was so intense it required my full attention to absorb the story as it unfolded. There was little room for my own emotional reaction. Now that it was over, though, I was struck with the conflicting emotional weight of the film.

I felt deep compassion for the offenders. Especially for residents who, like Bill and Tracy, were caught as children in the cycle of abuse and were never given a chance to be free from its terrible grip. I mourned for the residents who clearly experienced personal healing and recovery yet were unable to move forward in their lives on account of their crimes. My heart broke when Florida Transitions founder Nancy Morais appeared on screen and spoke about being a mother of someone who has committed such an atrocious crime.

I also felt a hot, heinous anger. I rumbled with rage. I am a mother. I had spent the last seventy-five minutes hearing stories of children who lost their innocence at the hands of disturbed adults. My instincts were on high alert. I was afraid. I felt unclean.

I could not move, so I wept. Other audience members stepped over my legs to leave the theater, and I slouched in my chair, pulling my winter coat across my lap. I wept because it was too much to look at it. It was too much to hold the shame and blame of this brokenness. It was too much to be a mother and a Christian and a human. Having eyes to see left me feeling vulnerable, broken, confused, and angry.

When Frida and Lasse Barkfors took the stage to field questions, their calm, generous demeanor warmed the room as best it could, but we were still raw. We were so rattled that the questions hewed to the safer, more technical aspects of filming. We asked about gaining the trust of the residents in such a short amount of time, about monitoring devices, about being foreign filmmakers on American soil talking about such a controversial issue. The questions raised by Pervert Park—the ones that we couldn’t put to words that night—are not easy. They are questions that work to connect the head, the heart, and the hand, questions that use vulnerability and brokenness and confusion and anger to cultivate new understanding.

The films we typically see in theaters are packaged nicely. They follow a plot line and develop characters fully. Pervert Park is a film in which nothing really happens. There is no central, unifying event. There is no movement within the lives of the subjects. There is little action. Yet, in this stillness is a film that has the potential to interrupt the narrative of life. As good films will often do, Pervert Park lifted all two hundred of us from different walks of life and for a brief moment placed us alongside the life of another. In a cold, quiet theater we were provided the space to see and feel the complexity of a world so often portrayed as one-dimensional.

This is what Jesus did. He interrupted the narrative. He separated foregone conclusions from living, breathing realities. He created space to consider a larger truth. He suggested that what we see might only be a small part of a bigger picture.

I have always been drawn to the most basic examples of Jesus’s humanity: the stories of how Jesus ate meals, how he was a member of a family, how he walked and slept, how he cried. These illustrations of Jesus’s everyday life allow me to grapple with his humanity. They fill in the gaps. They point to something larger than what we see. It is a natural extension of this interest, then, that the gospel stories I hold on to most are the ones where Jesus takes the time to recognize the humanity of others. These are the stories where we see Jesus pause because he notices the pain of someone in his path. This is where we see Jesus distinguish between someone’s identity and their being. As deep calls to deep, so it seems that Jesus’s humanity calls out to the humanity of the rest of us. It beckons us to recognize what we hold in common: we have bodies, we have spirits, we have minds, hearts, hopes, and fears.

To recognize the humanity of another is not a prescription for forgiveness or harmony. It doesn’t guarantee anything; but it does establish a firm foundation to build upon. To name the humanity of another can be a complicated, conflicting task. Furthermore, there is a real and terrifying risk that comes when this recognition puts in jeopardy the safety of our communities and the lives of our children. We are a culture that is in many ways risk-adverse. We want clear choices. We want labels. We want to know exactly what is in our food, who is living in our neighborhood, and where our tax dollars are being spent. We tend to like comedies that make us laugh, not documentaries that feel like horror movies. That is why looking at something (or someone) we would rather not see, something on the fringe of our society, poses a risk. Is there value in exploring the humanity of another, regardless of how heartbreaking and difficult it might be? Jesus seemed to think so. Is it risky to do so? Absolutely.

We spend much of our time looking only at the things we like to see. We curate our digital selves to portray a certain pleasing image. We carefully select the sources from which we get our news. We want people to like our Facebook statuses and the pictures we post on Instagram. Our lives are full but insulated, and with so much vying for our attention, it is easy to ignore the things we do not want to see. This is why Pervert Park is a relevant, modern parable. It interrupts the world we think we know. It asks us to consider the humanity of another. It creates space. Pervert Park is a film about the people no one wants as neighbors. It has the power to disrupt our perceptions of reality, and in the process of doing so, it reminds us that even the most vile members of our society still have heartbeats.

1. Frida Barkfors and Lasse Barkfors, Pervert Park, directed by Frida Barkfors and Lasse Barkfors (Copenhagen, Denmark: De Andra, 2014), screened at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival.