There is a beloved story among whiskey-drinking Nashville Christians involving the regional oddity that is Will D. Campbell. He was a double-traitor of sorts, first to poor, white southerners when he became a civil right activist and then later to his fellow activists who wondered what would possess a man to minister to the racists. The story goes that an unbelieving friend, who routinely pushed Campbell’s buttons, once asked him to describe Christianity in ten words or less and Campbell replied, “We’re all bastards but God loves us anyway.”[1]

In 1965, Campbell was grieving the loss of a young seminarian, Jonathan Daniels, who had been murdered in Alabama by a sheriff’s deputy. Daniels had participated in a demonstration and was walking to a grocery store when he was confronted by Thomas Coleman, whose shotgun blast killed Daniels instantly. In the midst of his grief, Campbell’s friend pressed him on his past definition of the faith, asking, “Was Jonathan a bastard?”

“Yes,” Campbell replied.

The friend pressed further: “Is Thomas Coleman a bastard?”

Again Campbell replied, “Yes, Thomas Coleman is a bastard.”

Finally, Campbell’s friend drew closer and asked the question Campbell credits with changing his life: “Which one of these two bastards do you think God loves the most?”[2] The question helped Campbell realize he had succumbed to an agenda that simply mirrored the prejudices of white racists. Campbell explains:

I was laughing at myself, at twenty years of a ministry which had become, without my realizing it, a ministry of liberal sophistication. An attempted negation of Jesus, of human engineering, of riding the coattails of Caesar, of playing on his ballpark, by his rules and with his ball, of looking to government to make and verify and authenticate our morality, of worshipping at the shrine of enlightenment and academia, of making an idol of the Supreme Court, a theology of law and order and of denying not only the Faith I professed to hold but my history and my people—the Thomas Colemans.[3]

Daniels’s death led Campbell to conclude, “One who understands the nature of tragedy can never take sides.”[4] This is not to say that Campbell ignored injustice; he did not. Much like a battlefield physician, Campbell committed to performing the equivalent of spiritual triage to the walking wounded he noticed everywhere. So Will Campbell, who had once been the only white man at the formation of the Southern Christian Leadership Council—to name but one of his many high-profile appearances throughout the civil rights movement—became a minister to any in need of one, especially the bastards.

My own turning point didn’t hinge on such a sudden epiphany. Instead, it was programmed into my genetic code, a latent turn of face just waiting to emerge. I was a fairly typical Christian college student. Like most twenty-year-old men, I conceived of my body as little more than a vessel for satisfying my appetite. Beyond that, my evangelical, quasi-gnostic upbringing had trained me not to notice bodies, specifically not my own body.

But cancer abruptly ended those reflexive habits. I needed notes from missed classes; I needed a hand in the cafeteria. Sometimes I needed simple errands run for me. The thing I had come both to count upon and completely ignore—my body—was now exposed and failing me in undeniable ways. What was invisible—my illness—became visible to everyone, and hence, my body also became visible. The radiation therapy marked me with red and pink splotches. My body became a map of my illness and treatment; the surgical scars, a point of fascination for many of my friends and acquaintances.

At the same time I was undergoing treatment, my college roommate and best friend was losing a childhood friend to leukemia. I survived; the other guy, who I never met, did not. My evangelical tradition, I believed, called me to affirm that “God has done this to me. God has done this to him, too. God has designed this cancer specifically for me in order to bring about His unknowable purposes and glory.”[5] This dose of survivor’s guilt complicated matters. Why was I going to live while so many others had not? I obsessively sought a causal relationship between my actions and my survival, for some past choice or unknown variable that might allow me to maintain the facade of control over my fate. Imagining such scenarios was much more comforting than accepting the randomness of the genetic lottery, or in Stanley Hauerwas’s words, acknowledging “illness as pointlessness” or as “an absurdity.”[6]

Reinhold Niebuhr claims that securing life, possessions, or anything one loves against loss is the primary impetus to sin. In other words, as we fully recognize our creaturely limits, anxiety sets in and life can becomes one large effort to “overcome contingency.”[7] Anyone who has endured serious illness inevitably becomes familiar with these feelings of anxiety. Social ostracism, fear, grief, loneliness, and a nearly constant feeling of loss, as if you are losing everything—these are the companions of the sick.[8]

Two years into remission, I did not feel eternally grateful for the gift of life. I did not know a single person who could relate to my circumstances. I felt alone with my anxiety and loss. I felt like a lousy bastard who thought about dying every single day.

My illness thrust me into a vulnerable space, and in that space I became a little more human. When I finally noticed my own body and came to grips with my mortal shelf life, other bodies also came into focus. Reflection did not come easily during the trauma, but I was becoming a student of a new pedagogy, a pedagogy of bone and blood.[9] As a cancer survivor, I experienced a brief period of shadowless participation in which my bodily sovereignty was not my own, and it led me to two lessons.

My first realization was that the dissipation of my illusions of bodily invisibility was directly connected to the sense of isolation I experienced during my illness, and this forever altered my understanding of racial identities. We whites tend to exist as if we are unmarked racially; we exist within a sociopolitical norm where personal autonomy is taken for granted. We experience the world in a way in which white begins to function societally as synonymous with normal or universal.[10] Such invisibility provides the cover for evading necessary yet difficult conversations on race, either by discounting the significance of racial identities or adhering to “colorblind” ideologies. This polite form of racism has insulated us whites from being confronted by our subterranean privileges, thus creating a “white fragility” that “builds white expectations for racial comfort while at the same time lowering the ability to tolerate racial stress.”[11] Simply put, the great privilege of whiteness is that I am rarely confronted by my race because our world rarely beckons me to do so.

Toni Morrison suggests that the refusal to discuss race, or to actively ignore it, is thought to be “a graceful, even generous, liberal gesture” by whites on behalf of people of color. This gesture, though, actually enforces silence on all racial topics, merely allowing “the black body a shadowless participation in the dominant cultural body.”[12] The longstanding invisibility of people of color, coupled with the freedom of whites to navigate society unmolested, creates an empathy gulf for most whites that is difficult to bridge. Our ignorance of bodily existence (or racial particularity) has meant that all interruptions or challenges to that norm are ostensibly perceived as a threat to peace or order.

Because I felt utterly alone, the second lesson I learned during cancer was the importance of presence. During that time, I became a curiosity. In the pristine white, evangelical world in which I lived, it was seen as impolite for my peers to mention my illness or obvious bodily changes, yet they made me the subject of constant attention. James McClendon calls “presence” a virtue, the practice of “being there for and with the other. . . . It is refusing the temptation to withdraw mentally and emotionally; but it is also on occasion putting our own body’s weight and shape alongside the neighbor, the friend, the lover in need.”[13] For McClendon, presence refers to the intrinsic worth of the body, and among American traditions he saw it exhibited most clearly in the faith and theology of the black church tradition, for whom God’s presence served as a balm to their collective suffering in America. Those who endured in body, mind, and soul a holistic assault upon their personhood and moral agency were led to, in its best incarnations, a holistic Christian ethic.

By experiencing a small measure of fleshly suffering, I was opened up to empathize with others, if only in some miniscule, reiterative way. To come close to me was to experience a primer in conceiving of, perhaps for the first time, one’s own mortality. McClendon notes that the inverse of presence is not “absence” but rather “avoidance or alienation.”[14] The blessing of Christian community is that people drew near to me, even if they did so because of curiosity or theological perspectives I might not share. As my body was threatened, weakened, and vulnerable, I could no longer navigate my day-to-day existence surreptitiously. I was the subject of concern, prayers, and mystery, whether I wanted to be or not. I experienced a transformative moment in which I accepted my humanity and thereby embraced the suffering community around me, a community to which I wasn’t even sure I belonged. Hauerwas explains this journey well:

Once we understand how expressing pain and suffering can delegitimate theodicies meant to legitimate the status quo, then we can see that our willingness to expose our pain is the means that God gives us to help us identify and respond to evil and injustice. For creation is not as it ought to be. The lament is the cry of protest schooled by our faith in a God who would have us serve the world by exposing its false comforts and deceptions.[15]

Back to Campbell for a moment. Campbell’s life exemplifies for me how white southerners can be transformed through the suffering of others. Because he grew up in deep poverty himself, Campbell knew well that the poor, white or black, could not shelter themselves from the harsh realities of disease and death. This fact crystallized for him theologically after witnessing the funeral procession for Noon Wells, a black tenant farmer who worked for a family member. He recalled Wells’s mother leading a train of mourners who echoed her loud cries of “Lord Jesus” and her supplication for Christ to “bring my baby home!” These “Jesus sounds,” as Campbell called them, were the pleas of a peasant mother in Mississippi to the son of a poor Jewish mother who surely understood her plight and pain.[16] Campbell recounted the childhood memory, saying the sounds were “the articulation and recitation of two hundred years of pathos. An emancipation which still had not reached them, or us, if in fact it had reached anywhere at all.”[17]

Campbell remained connected to black suffering, specifically through his work in the civil rights movement, but the work would cost him dearly with his brother, Joe, a man incapable of finding community or healing anywhere. Joe Campbell suffered from bouts of deep sorrow, addiction, frequent violent outbursts, and sociopathic behavior, but he also showed occasional moments of lucidity, like for example in this racist rant aimed at Will:

You think you’re going to save the . . . South with integration, with putting niggers in every schoolhouse and on every five-and-dime store lunch counter stool. . . . What you’re saying is that you’re going to use the niggers to save yourself. What’s so Christian about that?[18]

Joe’s racist, addiction-fueled invective was meant to get under his brother’s skin, and it worked. Will Campbell was learning the cost of presence: it meant stepping into tragedy, which also meant no longer denying the systemic forces that oppressed poor whites like his own family members. Will would lose his brother not long thereafter, yet his ministry—to Klan members, murderers, and prisoners—transformed by the confrontation with Joe, can be read as an attempt to save those similarly diseased like his brother and the people of his homeland. Campbell allowed himself to be misunderstood in order to be a minister to anyone and everyone. He was never quite at home again on any of the acceptable political or denominational teams. He was a bastard for the rest of his days.

In each of the vignettes I have shared about Will Campbell, he was confronted by death, with each confrontation helping him understand a new aspect of his ministerial calling. They were conversion experiences for him. I can relate. Cancer was my second baptism.

Just as baptism prepares us for death by submerging our old self beneath the waters, cancer revealed to me a world that did not require my presence. It also showed me that while I was not essential for the world to keep spinning, I was loved deeply by my community. The trauma of my illness meant I neither questioned the reality of my death ever again nor did I wonder about my worth to loved ones. I also heard, in new ways, the lessons from my parents that not every child of God felt loved in this world; not everyone got a fair shake. Not everyone was given the benefit of the doubt by powers and authorities.

For this reason, when I hear the death wails, I must be moved from compassion to action. When I hear the Jesus sounds, I am called to rage against death and for those who are its routine targets. When I hear Eric Carner gasp “I can’t breathe,” it must be an echo of my own baptismal vow, and I must hear it as a man’s last affirmation of his humanity and as condemnation of the forces that killed him. As Christopher Marshall explains in his exegesis of the parable of the Good Samaritan, Jesus calls us to be motivated by “sharing in [the victim’s] personal suffering and isolation.” Compassion for one’s neighbor “is the emotional signal that we all participate in a common stream of humanity and it is this shared humanity . . . that evokes the obligation to love others as creatures of equal worth and rights as oneself.”[19] If Jesus truly shows us how we are to be human, then our ears and our hearts must be trained to hear these death wails; otherwise, we deny something essential in our created intention.

Of course, not everyone hears immediately. Cancer and remission has not magically kept my indignation in check against those who do not share my newfound racial revelations, but by the same token, surviving cancer has not granted me license to become insufferable to those same people, for I know that I have not been magically cured of my racism. I received a harsh vessel of transformation that mercifully does not come to everyone, and for that reason the lesson of the last seventeen years since my remission has been that I am called to welcome all and minister to all. The Jesus sounds changed me forever, but not everyone has heard them. Until they do, Jesus remains for everyone, especially the bastards.

[1] Campbell, Brother to a Dragonfly, 25th anniversary ed. (New York, NY: Seabury/New Continuum, [1977] 2009), 220.

[2] Ibid., 221.

[3] Ibid., 222.

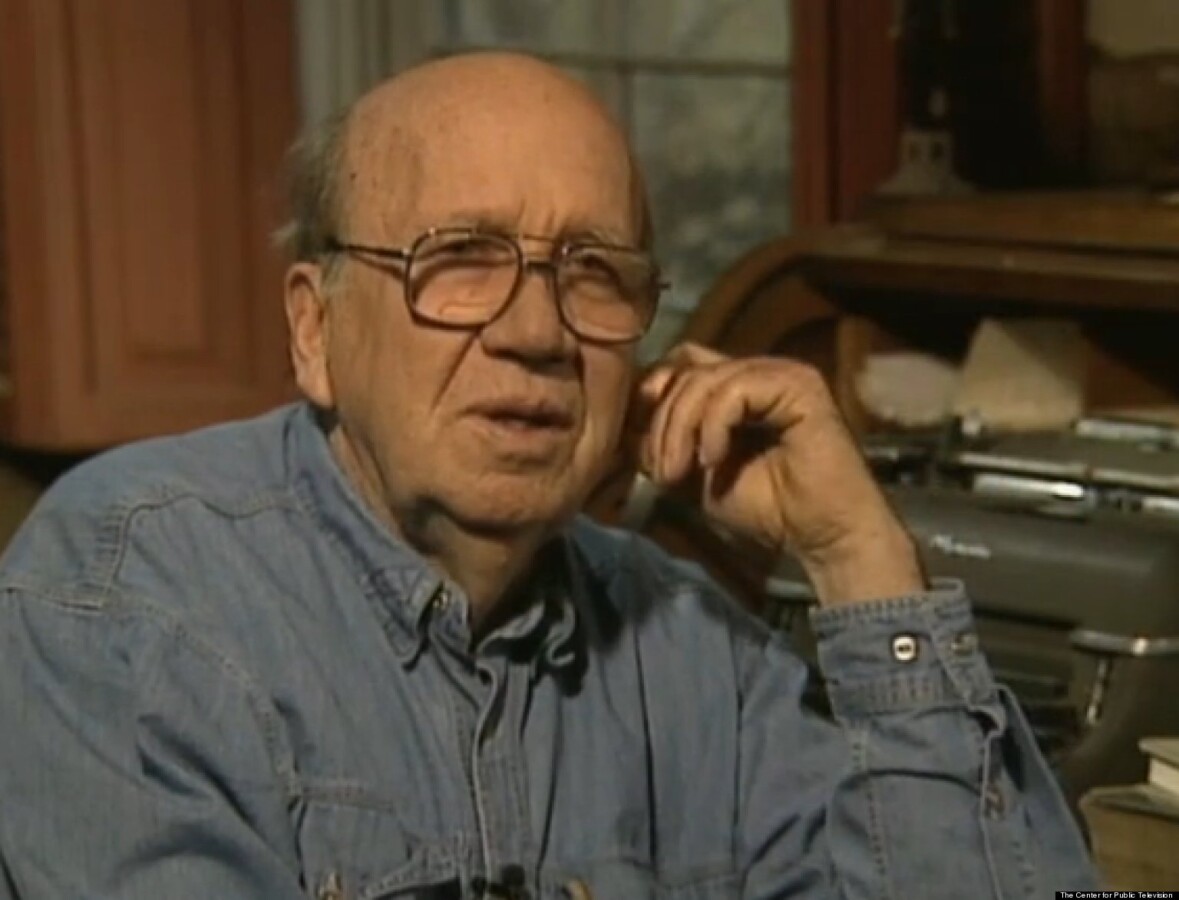

[4] God’s Will, DVD directed by Michael Letcher and Ossie Davis (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Center for Public Television and Radio, 2000).

[5] See John Piper, Don’t Waste Your Cancer (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2011), http://www.desiringgod.org/books/dont-waste-your-cancer.

[6] Hauerwas, God, Medicine, and Suffering (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1990), 63.

[7] Niebuhr, The Nature and Destiny of Man, vol. 5, Human Nature (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996), 185.

[8] Jann Aldredge-Canton, Counseling People with Cancer (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 1998), 82–83.

[9] See James K. A. Smith’s recent works in the Cultural Liturgies series, Desiring the Kingdom and Imagining the Kingdom (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2009 and 2013).

[10] James Cone raises this matter in God of the Oppressed, rev. ed. (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1997), 42f.

[11] Robin DiAngelo, “White Fragility,” International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 3, no. 3 (2011): 55.

[12] Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), 9–10.

[13] McClendon, Systematic Theology: Ethics (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1986), 106.

[14] Ibid., 107.

[15] Hauerwas, God, Medicine, and Suffering, 82–83

[16] Campbell, Brother to a Dragonfly, 60.

[17] Ibid, 62.

[18] Ibid, 201.

[19] Marshall, Compassionate Justice: An Interdisciplinary Dialogue with Two Gospel Parables on Law, Crime, and Restorative Justice (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2012), 73 and 78.