To attempt scorpion pose, or its cousin pincha mayurasana, feather of the peacock pose, get on your hands and knees, and then put your forearms on the mat, shoulder distance apart. Press your palms into the yoga mat, roll up onto your toes, and lift your hips as high as possible. Push your heart forward while engaging your abdominal muscles. See if you can resist the unexplainable fear of being upside down; lift one leg at a time off the ground.

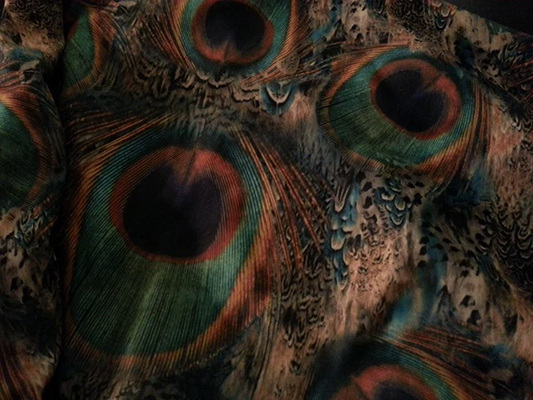

Stay on your forearms and notice what happens. That pull across your sternum? These are muscles that need to be stretched. What seems excruciating and awkward becomes doable when you stop hunching your shoulders and instead let your sternum press forward while your torso holds the rest of the body up. If your back and shoulders are open enough, you may choose to let your toes reach for your forehead, turning the peacock feathers into a scorpion’s inverted backbend.

My toes have never touched my nose or even bumped my forehead. On most days, I keep my toes straight above my hips for a count of five, four, three, two, one before they bump into the wall that’s there to keep me from falling over. Or I teeter back to the mat and thud into a clumsy child’s pose. Some nights, I kick my legs up and down off the floor, knowing they aren’t going to balance over my head. And then sometimes they do balance there, and I panic—the fear is not of falling but of being airborne.

That panic then gives way to visions of falling over, neck torqued on the mat, back snapped in a backbend. These aren’t unreasonable fears. One morning while attempting a headstand, I lumbered sideways and tumbled onto my yoga partner’s arm while he rested in savasana. I rolled into fetal position and laughed, terrified. You can break things turning upside down.

In church one August Sunday, I read the date on the bulletin and remembered it was my ex-husband’s birthday. This particular weekend, Facebook was full of announcements of my college friends’ ten-, twelve-, or fifteen-year anniversaries. “Eleven years ago today we swore to remain faithful to each other forever,” their status updates announced. “Through the hard times and the hardest times of our lives. I love you, sweetie!” I wanted to be impressed, but I couldn’t help feeling that they were being committed at me, as author Glennon Melton might say. The overt and implied message—we didn’t fail—meant that people like me sort of did.

Two thin, long-legged girls come to my Wednesday night yoga class. When they move into forearm balances, their heart chakras (that is, their chest and back muscles) are very open. Their peacock feathers are exuberant. I am the teacher, and I still use a wall most of the time, not because I can’t kick up but because I kick up too timidly if I don’t know something is there to stop me. Their boundless flexibility doesn’t stop there. When the rest of the class, myself included, wiggles into tentative splits, their legs slide all the way onto the ground, their backs arched and long, arms reaching toward the ceiling.

Yoga philosophy teaches non-harming and non-attachment: don’t hurt yourself, don’t beat yourself up, and don’t cling to your limitations or your successes. Yoga also gently suggests that our weaknesses are excellent educators. At a certain point, my body will describe my yoga—my bones and their length will determine my openness in wheel pose or downward dog. The best yoga teachers advise students to work toward an ideal while also respecting the body’s abilities. If I am bobbing up and down in a flimsy, cooked asparagus of a headstand, and the person next to me is in a wide-legged, one-armed handstand, I shouldn’t be obsessed with what either of us can do. I shouldn’t envy her body’s abilities. But of course, I’m human. Shoulds and should nots are there to make us feel bad. So my favorite yoga teachers simply tell their students to always “keep your eyes on your own mat.”

I often look back on my former marriage and then at my yoga, and I think that somewhere in there is an imperfect metaphor. My skeletal structure, my thoughts, and my emotions limit my backbend as well as my vulnerability and trust. Our bones limit what we can do. But what surprises me is that my bones are not fixed and brittle. They are live, malleable tissues. This skeleton, this heart, this collection of organs and thoughts and sensations can slowly shift.

After moving from England to Indiana eight years ago, I wrote a list of the British things I’d begun to miss and turned it into a poem. Sometimes now I play a similar game—what would I have missed if I’d never married him? The answers come as images from my difficult, emotionally exhausting but beautiful life in Great Britain: a path along a winding river in the town where I moved to be near him, the hills I climbed to get home, the long walks under a multilayered sky as the sun set on the cathedral skyline, and the daffodils waving under a train trestle. Some of these images include people, like Vera, my first yoga instructor, or my friends who came over for pizza and brownies. Maybe in my time alone in Scotland I would have learned how to be alone in a country that was never quite empty, how to sleep in a country that never quite got dark on summer nights, but if I hadn’t lived in Durham, I wouldn’t have crossed all those Norman bridges. I would never have attempted to outrun the sculls and eight-man boats flying down the river in the early September mornings. Even if I could rewrite my history, I can’t decide if I’d want to.

Mostly I wish that my ex had stayed that guy from college. In a photo from before we dated, I’m standing on a chair in my friend’s townhouse wearing men’s cargo pants, a T-shirt, and a grin. Had I let him float off into the ether with my other college friends, perhaps that grinning girl might have stuck around. Someday my ex and I might have ended up as friends on social media, or we might never have talked again after graduation. “I’d take that,” my friend says of his ex. “I’d give up the good times to not have gone through hell with her.”

I didn’t realize, though, that when I ended our marriage it would make me regret the small moments of happiness. Once we rode a boat to Mackinac Island, hiked through Yosemite, strolled down the hill to Durham City, hand in hand. Once we drove to an overgrown urban neighborhood to adopt a puppy. I expected to regret the divorce and the amputation of his life from mine. What I didn’t expect was to look at the puppy, now a seven-year-old dog sleeping at my feet, and wonder if he’d be on that list of lost, missed things too.

I attended a power yoga workshop in Fort Wayne, and before our class, the instructor, Bryan Kest, talked at length about the Sanskrit word asana, which Westerners define as a “pose,” “manner of sitting,” or “to sit quietly.” Everything can be an asana, Bryan told us, if you do it in a way so that you are (metaphorically) sitting quietly, with focus and calm breath. Instead of merely running down a track, you could be running-asana. You could be standing-asana, meeting-asana, eating-asana, washing-dishes-asana—with focus and calm, everything becomes yoga.

But during my marriage, even my yoga wasn’t focused or calm. The version of me standing on a chair, grinning, no longer existed. I was always looking ahead to my to-do list or checking over my shoulder for overdrafts and outbursts of anger. If my husband was at home, I didn’t like practicing yoga. He made fun of the instructors on my yoga videos. He would talk to me while I was practicing—it is very hard to breathe only through the nose only and also talk—or touch my butt as I tried to hold warrior three. Once in a hotel room while I practiced crow, an arm balance, he said he wanted to knock me over. Down dog, he said, looked like a great sex position. Any balancing pose was an excuse to make me lose my balance.

What I’ve only recently realized is that my lack of calm in our marriage was connected to a very strong feeling of being unsafe, and nothing felt as unsafe as sex. After a few years of marriage, I hated practicing wheel, a backbend, at home unless I was alone. In this position I felt less like light and more like a model for the Kama Sutra, and my breath became shallow and panicked rather than focused and attentive. I found it was hard to focus and tune out distractions if I was concerned about getting molested and then judged for falling over.

On the morning I left him, I tiptoed out of the guest room. The night before I’d autopilot-packed a bag without him noticing, then hid out in the bathroom to text friends for places to go. When I snuck out of the house, I took just long enough to stroke the long, gentle muzzle of my dog and to rub his ears, telling him it would be OK. I took a deep breath. This was leaving-asana.

Each September brings an ex-anniversary with complicated, though sometimes happy, memories. The night before our wedding, I drank Guinness in a pub with my grad school friends, college roommate, brother, soon-to-be-husband, and aunt and uncle. Of all the wedding memories, it is my favorite, the one that doesn’t weigh me down.

When I must look through old photos, the muscles of my heart begin to catch and pull. It feels like taking a nature walk through landmines—look out for the bombs, but not so closely that you actually look at them. Someday I’ll delete the photos that include my ex, but in the meantime they linger, along with the wedding photo album, the personalized wedding plate and bowl from my grandmother, my wedding dress that sleeps in a box in my hallway closet, a box of his belongings on a file cabinet.

The catch in my heart, the uneasy stirring, tells me it is time for them to go. When teachers of yoga speak of non-attachment, they are speaking concretely and abstractly—they mean that we are not to become too attached to our things or our beliefs. Travel light, the yogis believe. When you load up too much and then ignore what you carry, your back hunches forward and the heart chakra closes down. Look: the peacock carries nothing but its own exuberant plumes. To do risky things, to be risky, carry as little as possible.

Right before my second ex-anniversary, my ex sent me expensive jewelry, complete with a sentimental note and “all [his] love.”

Stop. Keep your eyes on your own mat, Katie, and turn to face the wall.

Soon after, I mailed the box of his stuff, including the jewelry, back to his mother. The tight shoulders, the constricted heart, began to work themselves open.

Statistics on divorce, while often miscalculated, still tell a story that most Americans are bad at marriage. The stats suggest that some of us even revel in marital flippancy. I wonder if we need this flippant attitude toward a dead marriage in order to live with ourselves. No matter how much grace a divorce brings, it still feels like the wrong kind of exclusive club, the membership we all dreaded. Some of us are happier for it but still sobered by what we’ve done. Some of us, like me, feel doubts about whether we did it right. Some of us reach for pebbles and slide them into our pockets. For memory? For safekeeping? For throwing back? I rub the rocks through my fingers. I haven’t decided yet.

Some of my favorite yoga poses are the ones that hurt the most. Warrior one twinges my back and wheel feels like I’m bending a steel rod in my spine while the universe balances on my bellybutton. When talking students into pigeon or other hip-opening poses, yoga instructors remind them that hip stretches can relieve back, neck, and head pain. They also note that the hips store our stress and our trauma. We ignore this trauma and allow it to build into pockets of stress that cause chronic pain. The messages of the body hide here. In pigeon pose, we lean our bodies forward as far as they can over a knee that is bent to the side so that our shin becomes parallel with our shoulders. The other leg stretches out behind us. Sometimes when I am in pigeon, what I’ve buried and forgotten makes me want to punch the floor. Keep breathing.

And I keep practicing being a peacock, trying to float into and stick pincha mayurasana. I start by practicing yoga with my feet on the ground. Then, when I’m ready, when I feel the catch in my heart, I get on my forearms and knees—heart open, stomach pulled tight—and turn myself over. I try to do it without flailing, kicking, or falling over, but if the only way I can do it is ugly, then I do it ugly. I try to stay there, try to keep breathing, try to point my toes toward the sky, my body a brilliant feather announcing it is here and not afraid.