Recent events in North Dakota illustrate the violence that is inherent in our fossil fuel addiction and the role that nonviolent resistance plays in unmasking this violence. The Dakota Access Pipeline will carry about 470,000 barrels of oil a day from the western oil fields of North Dakota to Illinois. That’s about twenty football-field-sized swimming pools of oil every day. Energy Transfer Crude Oil Company, the operator of the pipeline, promises that the $3.7 billion project would put millions of dollars into local economies, though most of that money would go to temporary labor.1

Initially, it was proposed that the pipeline would flow beneath the Missouri River, just north of Bismarck, a predominantly white community. This iteration of the proposal was rejected due to its potential threat to Bismarck’s water supply. Put simply, oil pipelines have a tendency to burst. In late 2016, for example, a crude oil pipeline leaked 176,000 gallons (about 3,500 bathtubs full) less than three hours away from the new proposed—and White House–approved—route for the pipeline, which will now pass through the ancestral lands of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, whose people regard the pipeline as an environmental and cultural threat.2 These are the lands on which the Sioux ancestors hunted, fished, and are buried.

This shift has been understood by some to be an example of environmental racism. Environmental racism occurs when one group, typically of a low socioeconomic status, is systematically exposed to environmental risk to safeguard other groups or communities, whose members are typically of a higher socioeconomic status. In this case, the charge of environmental racism is grounded in the early proposal for the pipeline—if the water supply of Bismarck were at risk, why isn’t the supply of the Sioux? Furthermore, the pipeline shift sits within a larger historical context of colonialism, including violated treaties, the murder of Sitting Bull, and the construction of a dam that flooded much of the Sioux tribal lands.3

In addition to the framework of environmental racism, the situation at Standing Rock can also be characterized according to René Girard’s ideas of mimetic desire and scapegoating. Girard identifies acquisition and appropriation as imitative—we want what others want. We feel pressured to keep up with the Joneses, and this leads to what Alain de Botton has described as status anxiety, the never-ending feeling that we are not as successful as our peers. Because resources are finite and sometimes scarce, this mimetic rivalry also creates competition, as two parties cannot always agree to share a single resource, say the right-of-way for a pipeline, and that competition can often turn violent. Think of shoppers during Black Friday sales. The desire for bargains and the mimetic conflict that results from limited stock has led to trampling deaths, accidents, assaults, and even murder.4 As Girard suggests, the reciprocity of desire generates a positive feedback loop in which violence tends to escalate.

One of the primary functions of religion, as Girard sees it, is to prevent the spread of mimetic rivalry through the performance of sacrificial ritual, a collective action in which a community attempts to purge itself of disorder. The sacrifice ritual is meant to mimic the mimetic crisis and bring it to resolution via the “scapegoat effect.” For example, the Chukchi people of the Chukchi Peninsula in Russia will kill an innocent family member of the perpetrator of a crime rather than the perpetrator of a crime; they do this to ensure they have a pure victim and to thereby bring reconciliation with the aggrieved party. According to Girard, these rituals do not necessarily solve the initial problem (i.e., the division in a community created by the competition for the same resource), but by uniting the various parties around a shared hostility toward the scapegoat who they deem responsible for the conflict, the violence of the conflict is transferred to the scapegoat and dissipated.5

Girard identifies scapegoats as those people who live on the fringes of society, people whose defining characteristics make them incapable of fully integrating into the dominant community. They are similar enough to broader society that they can function as a sacrificial substitute, but they are dissimilar enough that those sacrificing them can perpetuate their disassociation, their otherness, and deem them suitable for sacrifice. In the scapegoating process, the dominant cultural narrative defines who is at the center and who is at the margins. For example, the adoption of the Canaanite narrative by early colonists in North America marginalized the first peoples and legitimated both their transportation and killing. Now, in North Dakota we see that this same colonialist story continues with a scapegoating that is both personal and spatial. It is clear that in the case of Dakota Access Pipeline, the Sioux are being treated as scapegoats for “unfettered, unregulated capitalism.” And their homelands are treated as sacrifice zones: disposable, pollutable, and unworthy of the same environmental protection as white lands.6

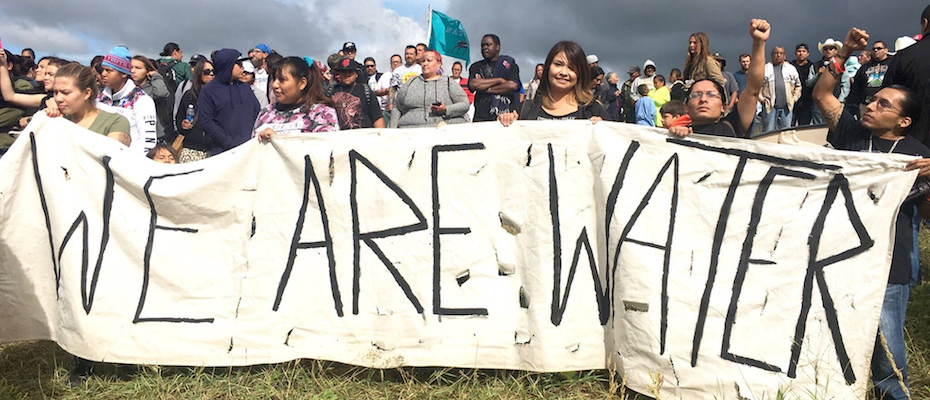

But there’s a subtle twist to these narratives. Girard argues that while scapegoating is common among religions, the Bible uniquely portrays the reality of the violence of the scapegoat effect. The biblical narrative regularly sides with its victim, reframing characters like Job or the woman at the well in stark contrast to the way they were viewed by the dominant society. And then Jesus changes everything, rendering sacrifice untenable in his nonviolent response, unmasking scapegoating violence in all its nasty horror. I argue that this is also what we’ve seen in North Dakota. The response to the pipeline proposal by the local Sioux tribe, other first peoples, and non-indigenous Americans has been nonviolent protest, seeking “to remain in peace and prayer.” According to Bill McKibben, the US federal government’s initial refusal to issue a permit for the pipeline represents a victory for indigenous nonviolent activism, one marked by prayer drums and sacred fires. Furthermore, their nonviolent response unmasks the violence of the system. However, such a victory has been short-lived, as President Trump signed an executive order to advance the construction of the pipeline.7

When the violence of a system goes unchallenged, it is normalized and taken as an essential part of the central narrative: the Sioux, together with their sacrificed lands, are scapegoats marginalized by the narrative of mimetic desire for energy resources, and the violence toward them is subsequently legitimated. A violent response by the Sioux would only reinforce this narrative and produce further reason to scapegoat them. However, a nonviolent response demonstrates the violence of the system as abnormal, recenters the nonviolent in the narrative, and opens up the possibility of transformation. The scapegoats become more human, and the system requiring their sacrifice is challenged as the scapegoat becomes unsacrificable.

Moreover, the violence of the system was made even more clear by the way law enforcement responded to these impediments to economic progress. Authorities used rubber bullets, pepper spray, and water cannons against demonstrators, injuring hundreds. The water cannons were used in below freezing temperatures, with some protestors suffering hypothermia as a result. At one point, the North Dakota governor wanted to block supplies of food and building materials from the site in order to starve out protestors, though he later backed down. In order to justify the violence, police alleged that protestors threw rocks and propane bottles at them, which the protestors deny.8

One further sign of the value of unmasking violence was the apology made by members of Veterans Stand with Standing Rock to Sioux spiritual leaders. These veterans traveled to North Dakota, joined the protests, and then took part in a forgiveness ceremony in which they publicly apologized for historic injustices against the Sioux and their land, ending with “We’ve come to say that we are sorry. We are at your service, and we beg for your forgiveness.” Some of these veterans had served in military units that have existed since the time of the Indian Wars.9 While there is a long way to go in addressing all of the historical injustices of colonialism in North America, this apology is an expression of the kind of solidarity between peoples that is required to disarm the violence of the dominant system.

***

By way of contrast to these events in North Dakota, the Oregon siege presents us with a different mimetic dynamic. The group known as Citizens for Constitutional Freedom occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge for forty-one days beginning in January 2016.10 The goal of their occupation was to force the federal government to turn over government-owned land to local ranchers, loggers, and miners. This was understood as a “return of land” from the government to the people. Once again, we find mimetic desire for control of resources, but in this case, wildlife was scapegoated, as the occupiers’ end goal prioritized land as a commodity or expendable resource. Furthermore, their mantra was oblivious to the colonialist history of ownership there, as the land’s original owners predate the US federal government, white ranchers, loggers, and miners; the land was occupied before European settlement by the first peoples. Such an understanding was lost in the white supremacist worldview of the Oregon occupiers.

The Oregon siege sits in a larger narrative that surfaced during the 2016 presidential election. From 2008 to 2012, the number of antigovernment groups in the United States increased more than 800 percent. Local unemployment, mimetic rivalry for land and autonomy, and racism have made white Americans subconsciously fear a loss of privilege. It is no coincidence that the rise of these antigovernment groups occurred during the Obama presidency. Cliven Bundy, the father of two of the occupiers (Ammon and Ryan Bundy), was himself involved in a standoff against federal agents in 2014. It was then that he wondered aloud whether black people would be better off enslaved. Such extremist views are, according to David Smith, the lasting legacy of the Revolutionary War with its narrative of violence. In turn, extremist politics is dominated by mimetic rivalry as various extremist groups compete against each other for power and followers.11 George Marshall shows how figures like climate-change-denier Myron Ebell, who led Donald Trump’s transition team for the Environmental Protection Agency, can see themselves as involved in a David-and-Goliath type of struggle against big government and a corrupt environmental movement.12 Indeed, mimetic desire extends to personal autonomy and freedom from control. However, this freedom is not upheld as a universal ideal but as a right of the white person who is at the center of the narrative of discovery, and in this narrative, big government and its concerns for environment and equality—i.e., liberal values—are the enemy. This is why the Oregon protesters scapegoated what they saw as an interfering federal government and the wildlife refuge that more directly represented that interference—they aimed to resolve the violence of their white supremacy.

The reaction from law enforcement officers to the Oregon siege, especially when compared to the response in North Dakota, is consistent with our overwhelming willingness to scapegoat environmentalists and indigenous peoples. In North Dakota, law enforcement officers used force against protestors who they claimed were armed with various makeshift weapons; they made more than 140 arrests in October 2016; and they even threatened the protesters’ food supplies. Meanwhile, in Oregon, federal agents tried to avoid confrontation with occupiers who were armed not with sticks and stones but firearms. The electricity was not cut off; supporters were free to join the occupation; and the occupiers could leave and return with groceries. And the arrest of the Oregon occupiers only came after many weeks, following criticism from Governor Kate Brown.13 The comparison to Dakota suggests a systematic difference in approach to white protestors—those rendered “patriots” and “constitutionalists” and hence unsacrificable—and indigenous people who are scapegoated for the American Dream.

Moreover, the result of the trial of the Oregon occupiers suggests that at least some members of the American public share the same mimetic desire as the Bundys and their allies. Seven of the occupiers were charged with conspiracy to impede federal employees from discharging their duties. The group also faced federal weapons charges that carried long prison sentences. Yet the jury was convinced that the defendants were involved in a legitimate protest against government overreach. They believed that the occupiers posed no threat to the public. The jury believed in the same central narrative, exhibited similar mimetic desires, and believed in the same scapegoats. Hence, the original seven charged Oregon occupiers were acquitted, while at a more recent trial two were found guilty of lesser charges.14

***

We have entered the geological era of the Anthropocene, a period in which humans have raised carbon dioxide to the highest levels in millennia, disrupted the natural ecosystem cycles by overuse of fertilizers, created a “hole” in the ozone layer, converted most of the global land surface to human use, driven species extinction rates up to one hundred times the natural background rate, and introduced novel entities such as plastics into the biosphere. Michael Northcott has applied Girardian thinking to these human inflictions on climate, identifying the mimetic rivalry of an increasingly borderless economic system wherein multinational corporations can compete with peasants for land in Africa, and climate change can increase regional conflicts over access to food and water.15 Such global forms of mimetic rivalry drive human agency to outstrip geological forces.

The Anthropocene requires sacrifice and scapegoats for its maintenance. At the economic and cultural level, this is made possible by what Northcott calls the “cult of consumerism.” Advertising, marketing, and public relations are all aimed at driving mimetic desire toward consumption. This desire is stimulated by encouraging a worship of novelty in the form of designer fridges, smartphones, and luxury cars. And while constant consumption is facilitated by the production of devices with built-in mechanical obsolescence, the mimetic desire for novelty and social status reveals that our cultural obsolescence is built in as well.

Underlying all of this material consumption is the need for energy, which is in turn linked directly to the extraction, transport, processing, and burning of fossil fuels. Throughout this process, the needs of some people groups and their homes are sacrificed or scapegoated so that material consumption may continue unabated. This phenomenon is well illustrated by the plight of the Sioux of North Dakota. In the near term, those who challenge the dominant narrative of the in-group—climate scientists, protestors, and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe—are made to be scapegoats, whereas the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge occupiers have successfully cast themselves as patriots and constitutionalists. The dominant narrative thus serves to justify both the threatened violence of the Oregon occupiers and the violence against the North Dakota protestors.

So what lessons can be learned from a mimetic analysis of these two events in order to challenge a system that produces such injustices? It is clear that nonviolence is an essential part of a strategy of unmasking the powers; mimetic violence escalates whereas nonviolent resistance shows violence for what it is. That said, this strategy can come at a cost, as evidenced by some of the injuries sustained. For example, in November 2016, Sophia Wilansky, an environmental activist from New York, was hospitalized suffering a severe injury to her left arm, narrowly avoiding amputation. Wilansky claims this is from a concussion grenade whereas law enforcement authorities maintain it was from a homemade weapon.16 It is an essential part of Girard’s model, which is supremely demonstrated in the cross; nonviolence unmasks and undoes the violence of mimetic rivalry but it does not come without costs.

Following Christ’s disruptive intervention, the church should be at the forefront of such modes of resistance. Christians have been involved in the Standing Rock protests, but the church has not owned nonviolence.17 Events like those at Standing Rock also provide opportunities for reconciliation between Europeans and indigenous people. Whether it is former servicemen recognizing the legacy of the military or Christians seeking to undo the damage of the doctrine of discovery, the scapegoating of indigenous people by Western civilization has done untold damage. In the long term, the whole earth and all people will be scapegoated by the cult of consumerism. Unmasking the powers will involve reconciliation between people and places everywhere.

- Jack Healy, “North Dakota Oil Pipeline Battle: Who’s Fighting and Why?” New York Times, August 26, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/02/us/north-dakota-oil-pipeline-battle-whos-fighting-and-why.html.

- Amy Dalrymple, “Pipeline Route Plan First Called for Crossing North of Bismark,” Bismark Tribune, August 18, 2016, http://bismarcktribune.com/news/state-and-regional/pipeline-route-plan-first-called-for-crossing-north-of-bismarck/article_64d053e4-8a1a-5198-a1dd-498d386c933c.html; and Bec Crew, “The Thing the Standing Rock Protestors Were Afraid of Just Happened,” Science Alert, December 14, 2016, http://www.sciencealert.com/that-thing-the-standing-rock-protesters-were-afraid-of-just-happened.

- Jeffrey Weiss, “Oil Safety or Environmental Racism? SMU Forum Shows Dakota Access Pipeline Divide,” Dallas Morning News, October 25, 2016, http://www.dallasnews.com/business/energy/2016/10/25/dakota-access-pipeline-oil-safety-environmental-racism-smu-forum-shows-divide; and Larry Rasmussen, “Environmental Racism and Environmental Justice: Moral Theory in the Making?” Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics 24 (2004): 3–28.

- See Girard, “Mimesis and Violence,” The Girard Reader, ed. James G. Williams (New York, NY: Crossroads, 1996), 9; de Botton, Status Anxiety (New York, NY: Vintage, 2005); and Melanie Dostis, “Five of the Worst Things That Have Happened during Black Friday Madness,” New York Daily News, November 24, 2015, http://www.nydailynews.com/life-style/5-worst-happened-black-friday-article-1.2445679.

- Girard, “The Surrogate Victim,” The Girard Reader, 10–12; 27–31.

- Ibid., 12–14; Alfred A. Cave, “Canaanites in a Promised Land: The American Indian and the Providential Theory of Empire,” American Indian Quarterly 12 (1988): 277–97; and Muriel Kane, “Chris Hedges: America’s Devastated ‘Sacrifice Zones’ Are the Future for All of Us,” RawStory, July 20, 2012, http://www.rawstory.com/2012/07/chris-hedges-americas-sacrifice-zones-being-destroyed-for-profit/.

- Christopher Mele, “Veterans to Serve as ‘Human Shields’ for Dakota Pipeline Protestors,” New York Times, November 29, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/us/veterans-to-serve-as-human-shields-for-pipeline-protesters.html; McKibben, “The Victory at Standing Rock Could Mark a Turning Point,” Guardian, December 5, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/dec/04/standing-rock-victory-turning-point; and Peter Baker and Coral Davenport, “Trump Revives Keystone Pipeline Rejected by Obama,” New York Times, January 24, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/24/us/politics/keystone-dakota-pipeline-trump.html.

- Healy, “North Dakota Oil Pipeline Battle,” New York Times; Julia Carrie Wong, “Dakota Access Pipeline: 300 Protestors Injured after Police Use Water Cannons,” Guardian, November 22, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/21/dakota-access-pipeline-water-cannon-police-standing-rock-protest; Josh Voorhees, “North Dakota Police Want to Deny Standing Rock Protestors Food and Shelter,” Slate, November 29, 1016, http://www.slate.com/blogs/the_slatest/2016/11/29/_north_dakota_police_will_cut_off_standing_rock_protesters_supplies.html; Terray Sylvester, “Standing Rock Protesters Won’t Be Blockaded as North Dakota Back Down,” Huffington Post, November 29, 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/standing-rock-protest-blockade_us_583df645e4b0c33c8e12ad8e; Derek Hawkins, “Activists and Police Trade Blame after Dakota Access Protestor Severely Injured,” Washington Post, November 22, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/11/22/activists-and-police-trade-blame-after-dakota-access-protester-severely-injured/; and Valerie Richardson, “Dakota Access Protestors Set fires, Lob Molotov Cocktails, Fire Shots in Face-Off with Police,” Washington Times, October 27, 2016, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2016/oct/27/authorities-begin-removal-dakota-access-protest-ca/.

- Sandy Tolan, “Veterans Came to North Dakota to Protest a Pipeline. But They Also Found Healing and Forgiveness,” Los Angeles Times, December 17, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-north-dakota-20161210-story.html.

- James Purtil, “The Oregon Siege Is Finally Over. What Actually Happened?” Hack, Triple J, February 12, 2016, http://www.abc.net.au/triplej/programs/hack/the-oregon-siege-is-over-what-actually-happened/7164530.

- For information on US-based hate groups, see “Hate Map,” Southern Poverty Law Center, https://www.splcenter.org/hate-map. On Oregon see Ashley Fantz, “Oregon Standoff: What the Armed Group Wants and Why.” CNN International Edition, January 6, 2016, http://edition.cnn.com/2016/01/04/us/oregon-wildlife-refuge-what-bundy-wants/; and cited in Purtil, “The Oregon Siege Is Finally Over.”

- George Marshall, Don’t Even Think about It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change (New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2014), 37; Henry Fountain, “Trump’s Climate Contrarian: Myron Ebell Takes on the EPA,” New York Times, November 11, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/12/science/myron-ebell-trump-epa.html.

- Carissa Wolf, Kevin Sullivan, and Mark Berman, “Final Oregon Occupiers Surrender to Authorities, Ending the Refuge Siege,” Washington Post, February 11, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2016/02/11/cliven-bundy-arrested-as-oregon-refuge-occupation-nears-possible-ending/; and Sam Levin, Nicky Woolf, and Damian Carrington, “North Dakota Pipeline: 141 Arrests as Protesters Pushed back from Site,” Guardian, October 29, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/oct/27/north-dakota-access-pipeline-protest-arrests-pepper-spray.

- Courtney Sherwood and Kirk Johnson, “Bundy Brothers Acquitted in Takeover of Oregon Wildlife Refuge,” New York Times, October 27, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/28/us/bundy-brothers-acquitted-in-takeover-of-oregon-wildlife-refuge.html; and Camila Domonoske, “2 Convicted of Conspiracy of Second Group of Oregon Occupiers,” NPR, March 10, 2017, http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/03/10/519690383/2-convicted-of-conspiracy-in-trial-of-second-group-of-oregon-occupiers.

- Will Steffen et al., “Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet,” Science 347 (2015): 1–17; Northcott, “Girard, Climate Change, and Apocalypse,” in Can We Survive Our Origins? Readings in René Girard’s Theory of Violence and the Sacred, ed. Pierpaolo Antonello and Paul Gifford (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2015), 287–310; and Philip Slavin, “Climate and Famines: A Historical Reassessment,” WIREs Climate Change 7 (2016): 433–47.

- Julie Carries Wong, “Standing Rock: Injured Protestor’s Father Says Police Account Is ‘Bogus Nonsense,’” Guardian, November 24, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/23/standing-rock-dakota-access-pipeline-sophia-wilansky-injury; Caroline Grueskin, “Protester Subpoenaed to Federal Grand Jury, Resists Testifying,” Bismark Tribune, January 4, 2017, http://bismarcktribune.com/news/state-and-regional/protester-subpoenaed-to-federal-grand-jury-resists-testifying/article_afbcec7a-0d8f-5221-b627-371d2c0f0c75.html; and Georglanne Nienaber, “Army Corps Issues Eviction Notice to Oceti Sakowin Camp at Standing Rock,” Huffington Post, November 26, 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/georgianne-nienaber/army-corps-issues-evictio_b_13238434.html.

- “Standing Rock Is a New Turn in Christian Ties with Native Americans,” Economist, November 27, 2016, http://www.economist.com/blogs/erasmus/2016/11/church-and-dakota-pipeline-protests.