A few months back my wife and I were reconciling our shared calendar when she asked a simple question that struck to the heart of our social identity and the future of our small family. She turned to me and asked, “Do you have next Monday off?”

The occasion, for which I was caught completely unawares, was the Labor Day holiday. I haven’t worked jobs that closely followed the calendar of federal holidays, and so it was welcome news to learn of this holiday in which we remember the efforts of those who went before us to establish many of the labor laws we understand to be normative today.

As I reflected on this newly discovered three-day holiday, I was struck by the way in which celebration influences identity. Memorial Day, Independence Day, Thanksgiving Day—these national holidays all speak to a national identity. These times of celebration and rest and travel speak to what we as Americans consider to be our story. Each American may celebrate these days somewhat differently or feel differently about the respective histories or myths that surround these holidays, but together we take these days, place them on a calendar, and celebrate in our own ways.

***

Advent is now upon us, and a new year has begun on the Christian calendar. If the timbre of our national holidays suggests we are a people of individuality and freedom, then Advent suggests a people of longing and waiting. Like Simeon shuffling his feet every day in the temple as he awaits the Christ child, we await his returning again. We are a people of waiting, and we are in good company. Recently, the lectionary’s Sunday readings have included selections from the First Letter of Paul to the Thessalonians, which was written to a people who waited and became concerned when Christ seemed to be taking his time.

What will happen to those who died before Christ came?

How much longer will this suffering last?

Why is he running so late?

Paul’s response is to remind them of the future, of the day when Christ will come and with a blast of the trumpet make them into a new people, a new creation. Until then we are like the Thessalonians, a people who wait, who anticipate, and who continue in faith as we recall the future. In this season of Advent, we recall the future and wait in hopeful longing for the fullness of Christ to be revealed. Still, one may ask, like the Thessalonians, what does it mean to be a people of waiting and how does one wait faithfully?

As I outlined above, a people group can be identified by their collective memory and the way in which they call to mind this memory through their annual celebrations. Just as we call to mind our American state of independence in July by lighting fireworks and grilling hamburgers, Christians call to mind the proclamation and promise of a renewed creation in the eschaton, when Christ comes again to make all things new. This history is summed up in the much-quoted narrative of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation, and we are a people who sit in the tension of the final two stages.1 But this is not a dispensationalism that calls us to prayerfully read the tea leaves, as if the eschaton were preceded by a discernible warning of the impending rapture. Instead, we are called to be a people who are identified in the very act of our waiting, a people who hold loosely to that which is not yet fully restored and who care deeply for the whole of creation with the conviction of a divinely inspired mandate.

While discussing the way in which God’s identity works within time and human agency, the late Robert Jenson states, “Her [Israel and the church’s] God is not salvific because he defends against the future but because he poses it.”2 Here, Jenson is adding his name to a long line of theologians who recognize that God’s interaction with creation and time includes both act and promise. In the action of Christ’s incarnation, life, death, resurrection, and ascension we recognize the acts of God which open up a new identity for the world. History moves forward in this progressing revelation based on each new act of God. The future of this seminal act in Christ’s coming is pushed ahead of us with the promise of his return. Therefore, the identity of the people called Christians is based on the act and promise of the person proclaimed as Christ. It is in this pilgrimage to the future that Jenson states that the eschaton belongs to lived history.3 Pushing against an existential—and ultimately gnostic—history, Jenson calls the church back to a lived reality that recognizes the acts of God in salvific history and moves us forward into a future that is open to the Spirit’s in-breaking as we await the advent of Christ and new creation.

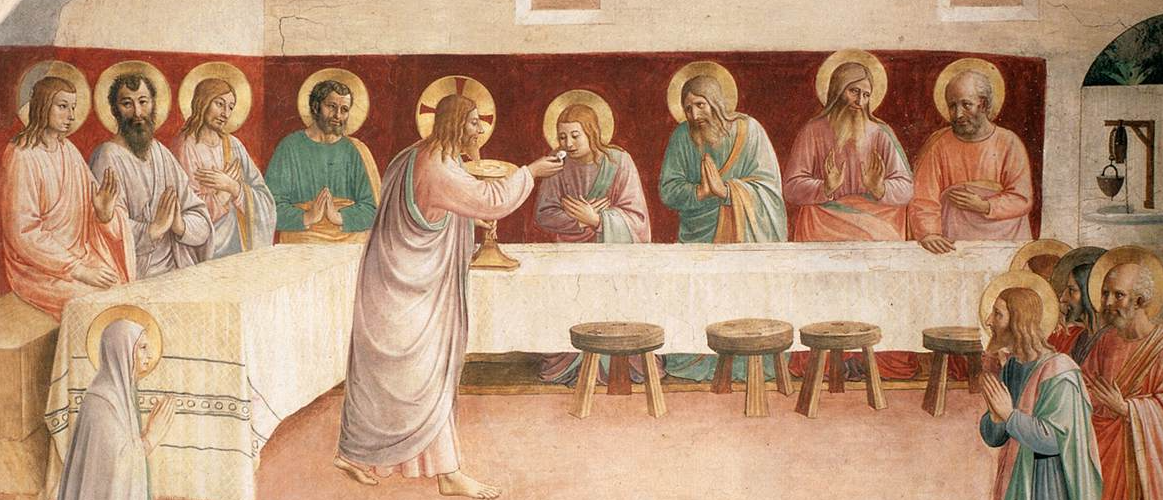

Yet how does one practice this identity of waiting? To answer this question and to avoid the pitfalls of thumb-twiddling, antagonism to creation care, and hypersensitivity to the assumed changes in the eschatological winds, I suggest the Eucharist.

Within this revolutionary act, we celebrate the group identity given to us by hoping the past and remembering the future.4 We hope in the proclamation of the apostles that over many generations has reached our ears and filled our hearts, and we remember the future by not only recalling the promises of Christ but by experiencing time in a new way. At the table, we collectively recall through the action of partaking in the bread and wine both the history of God’s acts and the wedding supper of the Lamb when he returns for his bride, the church. This seminal act grounds us in history, the present, and the promised future because we recall this narrative. In fact, one might understand the eucharistic celebration as an act of narrative therapy in which we discard the narratives that latch themselves to our worried hearts and take on a new story that is shaped by the acts and promises of Christ. This narrative challenges our nihilistic cultural fears of a closed future and instead offers us a new identity, an identity set in the acts and promises of Christ who has opened to us a hope for the coming future.

Of course, eucharistic theology may make some uneasy, as it hints at a metaphysics that has separated the church for many generations. Yet this is not a call to a particular soteriological cuisine, and it is not a call to a contemporary gnosticism that separates the bread from the Spirit. Instead, it is an invitation to recognize that our group identity is one that is enacted in a shared memory of taking the bread and the cup. In this memory our physicality is affirmed through the life-giving act of eating, and the promise is brought deep into our memory through the future hope of the consummation. In this act, time itself becomes a seamless garment for us to recall dramatically, in the partaking of the elements, the history of God’s redemptive acts and to hope the future as the celebration of communion becomes for us a reenactment of the wedding supper that is being prepared.5

Advent is thus a time of anticipation, of waiting, and of recollection—anticipation because we remember the future presented to us in the promise of Christ; waiting because we sit in between the now-but-not-yet of resurrection and consummation; and recollection because in the act of partaking in the Eucharist we, in a way, have been here before. We have feasted with the bridegroom who in the incarnation left his Father in order to cling to his bride and whose spirit is with us now, as close as our heart is to our chest (Rom. 10:8). In the acts of God and in the promises of Christ, we have a new identity, and we celebrate this identity by being a people of waiting—a people who remember God’s love for creation by recognizing that it is full of potential because of God’s act and promise, a people who sit in the tension and expectation of Advent much like children expectantly await the Christmas holiday in which presents can be opened and family visited and hopes fulfilled.

With the coming of Advent, the sentiment of Augustine rings true, “Our hearts are restless until they find rest in you.”6 We thus recall the acts of God, and we remember the promised future posed by God, and it is in these group activities that our hearts rest deeply in the presence of God, who both acts and promises through the incarnation of God’s Son. And it is in this story that we find ourselves and we wait. We become a people recognized by our waiting, by a dynamic waiting that propels history forward in the action of the Eucharist. We wait with the memory of the promise; we await the new holiday to be celebrated in the eschaton with the marriage supper of the Lamb.

- See N. T. Wright, Christian Origins and the Question of God, vol. 1, The New Testament and the People of God (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1992), 143–44.

- Jenson, Systematic Theology, vol. 1, The Triune God (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1997), 67.

- Jenson, Triune God, 67.

- See Robert E. Webber, Ancient-Future Worship: Proclaiming and Enacting God’s Narrative (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2008).

- See Laurence Hull Stookey, Eucharist: Christ’s Feast for the Church (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1993), 32.

- Augustine, Confessions, trans. Henry Chadwick (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2008), 3.