Several days after the birth of our daughter, my husband returned to the hospital to retrieve the placenta, which we had left behind in the flurry of newness and fatigue. The attendant at Labor and Delivery didn’t ask for his name or our date of delivery—she just retrieved a white plastic tub marked “placenta will go home with patient” and handed it over to him, as if it were the only afterbirth awaiting pickup. That seems likely, as in most hospital births the placenta is discarded immediately after exiting the mother’s body. Call it curiosity, call it creative research—I just wanted to hold onto it for a while, to inspect it, poke at it, and learn from it somehow.

As a sculptor, I am intrigued by the materiality of the flesh. I believe it to function as a microcosm that points to various aspects of the immaterial human experience. Years before ever becoming pregnant, I was already fascinated by the spiritual and cosmic significance of the human belly button and its relationship to the creative act. As a child I pulled at mine, trying to flip it inside out. Years later, as a graduate student, I poured plaster into it regularly, making castings of its negative space. The belly button is the first mark that life leaves on the body; it is a scar that points to our origins.

Many creation myths describe our world as originating from a central point. The Greek term omphalos (navel) can refer to various symbolic centers that are believed to connect the earthly and divine. Just as the human belly button marks our connection to (and inevitable separation from) our mothers, these so-called navels of the world are often associated with myths of cosmic origin, functioning as physical markers of the very sites at which our earth was supposedly born into existence. This symbolism can be found across cultures and religions, but in Christianity alone, we see a number of manifestations of the omphalos in Scripture: the tree of life, tower of Babel, Mount of Olives, Jacob’s ladder, Jerusalem, the holy temple, the cross, and ultimately, consummately, in the person of Christ.

I’m excited and inspired by the navel, umbilical cord, and placenta as both site and symbol of the simultaneity that is embedded in the human experience. Questions of origin and existence are constantly shaping how I think about my creative work, and my belief is that the work of the artist is primarily ontological. In the act of making, we participate in the creative act, in the ongoing shaping of being. As a person of faith, I am likewise convinced that the role of the artist is not merely to create beauty but also to help us investigate our own origins and to thereby discern meaning in the very fact of our existence. In this way, all creative acts can be seen as intermediary attempts to narrow the distance between the known and the unknowable, the material and the immaterial. Just as the human belly button marks both a connection to and a separation from our physical origins, the work that I make points to a similar simultaneity of opposites, referencing the body’s attraction and repulsion but also the immaterial void of human longing in us all, which I believe, ultimately, is rooted in a desire to comprehend our origins.

My own understanding and experience of the creative act is anchored in the fact that, above all, the original creative act, the shaping of existence by the creator God, is imprinted on my being. As createdness, I bear the image of my Creator, participating in this creative act in the specific creative activity of being both a mother and a visual artist. These are the two most potent ways through which I relate to and abide in my creator God.

***

In the natural and home birth community, it is not so shocking for a woman to keep her baby’s placenta. Placental encapsulation—a process whereby the placenta is dried, ground up, and made into pills—has recently grown in popularity, and many women claim there are benefits to consuming their nutrient- and hormone-rich placentas in the weeks after giving birth, praising it for helping with lactation and easing postpartum depression. Alternatively, some women choose to bury their placentas, a ceremonial act that honors the organ for its role in creating and sustaining new life.

The placenta is a wondrous organ. It’s a shame that the medicalization of maternal health has relegated it to the realm of medical waste because this means that most women in North America don’t get the chance to see their placentas, let alone ponder their significance. In her essay “Placental Thinking,” Nané Jordan considers contemporary and traditional uses of the human afterbirth, arguing that in claiming and honoring the placenta, we can come to better understand the sacredness of birth and the gift of life that mothers bring. Through what she calls “placental thinking” Jordan suggests that we “extend the metaphor of the placenta.” “Like the grand communicator,” she explains, “the placenta and umbilical cord define the paradox of the two bodies’ connection and separation.”1

Lauren Frances Evans, Knot Connected, in Omphalos, Jacksonville University, 2015, cardboard and latex enamel paint, 7 × 7 × 5 feet. Courtesy of the artist.

It’s become a customary practice in our current culture for fathers to cut the umbilical cord. This is a somewhat new phenomenon, given that fathers weren’t even welcome in the delivery room until the late twentieth century. The cutting of the cord is touted by some as a first rite of fatherhood, a way for a dad to participate in the birthing process and to bond with the baby upon his or her arrival. But my baby’s father didn’t cut the cord. I did. He and I became one in her making, yes, but at that very moment shortly following her birth, she and I then began the ongoing transformative process of becoming two.

I had been fascinated by the practice of the lotus birth (also known as umbilical nonseverance), in which the cord isn’t cut at all. Instead, the placenta is delivered, still attached to the child, and is cared for and kept near the child until it dries up and naturally detaches itself within several days. I was fascinated by the spiritual significance of this practice, its acknowledgement of the holistic and mystical process of childbirth, but I was not nearly committed enough to carry around a decomposing organ for the week following delivery. So instead I made the snip. Throughout the pregnancy, I became increasingly convinced that I ought to be the one—that it was my duty—to take that first step in our becoming two. In the act of cutting the cord, I acknowledged the personhood of my daughter apart from myself, which I continue to wrestle with to this day.

Numerous myths of cosmic origin attribute the birth of existence to a divine mother goddess. Greek mythology gives this primal mother earth goddess a name: Gaia. Traditional Christian orthodoxy affirms Mary as the bearer of God (Theotokos), and some Christians refer to Mary as the mother of God (mētēr theou). As the mother of Christ, she represents the mother goddess, not merely as myth but also as an incarnate being to whom we can relate.

In the Christian faith, we tend to exclusively attribute male characteristics to our Creator, using masculine pronouns and even calling God “Father.” But I think we lose so much of the rich imagery and significance surrounding the birth of the cosmos, as well as our relationship to our Creator, when we gender our God in this way. What if our creator God, in addition to being Father God, might also be thought of as Mother God? Imagining that this cord that connects us to the divine, becomes so much more potent for me when I imagine it in this real, embodied, maternal way.

I’ve also been frustrated and dissatisfied with the lack of liturgy within my faith tradition related to birth. The experience of becoming a vessel for this new life, and bringing her forth into this world, has been the most challenging and spiritually significant experience of my life. Two years have passed, and I am still grappling with all of its myriad meanings. I can’t help but wonder whether this experience of becoming two—of bringing new life into the world, of becoming a mother, of acknowledging the other in this way—might actually be understood not so much as a curse but as a blessing, if more history and theology had been written by women, or even with women in mind. I can’t help but wonder whether we might instead see birth as a sacramental rite that actually unites us in the divine expression of embodiment and incarnation.

I think often of Mary, the mother of Christ. She experienced, physically, what Christ describes when he speaks of bearing fruit in John 15. He says, “Abide in me, and I in you” (John 15:4 ESV). I imagine this indwelling he calls for can be known, on this earth, no better than in the maternal experience. Not only does the new life physically dwell in its mother’s body, but the mother’s blood pulses back and forth through the placenta and umbilical cord, in and out of the child’s tiny developing flesh. I think often of Mary, imagining how much more boldly she must have felt this, as a vessel for the young incarnate God. As all mothers do, she feeds him by her own flesh and blood, nourishing him with a life-giving vine. What a perfect picture of how God, too, feeds us.

In her essay “Placental Thinking,” Jordan describes the mother’s breast as an external placenta. When the cord is cut, the mother and child are no longer connected by the vine of flesh and blood. The mother’s womb is no longer the child’s home, but she quickly learns that her body still belongs to the child. Breastfeeding the child is just the next step in the slow, drawn-out process of becoming two. The child feeds on his or her mother, relying on her breasts for their life-giving sustenance, connected to her, latched, for the greater portion of that first year.2

In addition to their functional similarities, the placenta and breast can also be likened in their appearance. The tree of life has become a rich symbol for both, used throughout many natural and holistic birthing communities to resemble the complex network of vessels and the dynamic interchange of life-giving substance between the mother and child. Often the doulas and midwives who offer placental encapsulation will also make prints with the organ, pressing it onto paper to create an impression resembling the tree of life. Likewise, as part of a recent fad, some women took breastfeeding selfies and then superimposed an image of the tree of life on top of their so-called brelfies. A quick googling of “placenta print” or “tree of life brelfie” will yield countless examples of each.

In the nursing relationship, the mother and child experience an entanglement of selfhood and identification in the other. Particularly in the early months, the mother who exclusively breastfeeds her baby will find it extremely difficult to be apart from her child for more than a few hours at a time. If she is apart any longer, her breasts will become engorged with milk, leaking and soaking her bra as her body reminds her that her child needs to eat. I get nauseated just thinking about how my entire body ached that first time I was away from my daughter for longer than expected. I was excited to be away from her, to finally assert my independence from her, but I soon learned how badly I still needed her, my body physically in pain, longing for her presence.

***

Before becoming a mother, I always thought of attachment and separation as psychologies experienced by the child. I didn’t realize until experiencing it firsthand that, not unlike the blood circulating through the placenta, these psychologies very much go both ways. For example, I became so accustomed to sharing the bed with my daughter as I nursed her through the night that on the rare evenings she slept peacefully in her bed without me, I yearned for her. I couldn’t sleep without her in my arms.

Lauren Frances Evans, Becoming Two VIII, 2018, air-drying clay, 2 × 3 × 3 in. Courtesy of the artist.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this entanglement and have been working it out in a new body of small sculptural studies that I’ve entitled Becoming Two. At times I imagine vividly that my daughter and I are still connected by this cord. It’s a tug of war. At times we pull in opposite directions because we each want loose, while at other times we pull to be closer to one another. Often, I tug at the cord, longing for my independence from her, and more often than not, she tugs to bring me closer, unwilling to let me exist apart from her.

Author Jane Lazarre confronts a similar sensation in her fiercely honest and compelling 1976 memoir about early motherhood, The Mother Knot, a feminist classic that remains extremely relevant to this day:

After only several days of his life, we both felt that the breast was his. As he drew the milk out of me, my inner self seemed to shrink into a very small knot, gathering intensity under a protective shell, moving away, further and further away, from the changes being wrought by this child who was at once separate and a part of me. Frightened that he would claim my life completely, I desperately tried to cling to my boundaries. Yet I held him very close, stroked his skin, imagined that we were still one person.”3

My two-year-old, still nursing, is only just now beginning to understand that my breasts don’t belong exclusively to her. Many women, particularly in North America, wean their babies long before they are ever able to make this distinction, before they even learn that their mothers are themselves separate entities.

My daughter began saying “daddy” quite some time before saying “mama.” At first we found it odd, since she spent so much time with me, and she always seemed to favor me over my husband. But then my mother made an astonishing observation: “She still sees you as an extension of herself.” It made sense then, all of a sudden, that if I wasn’t a separate person, if I didn’t exist apart from her, then I didn’t need a name to be distinguished from her. I was her. We were one.

As I think about weaning, about the impending end to our nursing relationship, I think often of Mary, so often depicted throughout art history with the Christ child at her breast. I imagine that she nursed him well into toddlerhood. I imagine him asking excitedly for “boobie” like my toddler does so often. I imagine how much more intensely she must have felt the simultaneous letdown of attachment and separation, of becoming two, not only with her child, but also with her God.

Simultaneous letdown occurs when both breasts release milk at the same time. This phrase has come to encapsulate much of the complexity of motherhood for me. The term letdown refers to the physiological response triggered by the release of oxytocin, the so-called love hormone that is produced when a baby begins suckling at the breast. During the letdown reflex, milk begins to flow more freely, often spraying with force into the back of the baby’s throat. At times, even when the baby isn’t nursing, an increase in oxytocin can cause a lactating woman to letdown without warning, such as when she hears a baby cry or looks at a picture of her baby. Not every mother experiences simultaneous letdown, but I did, and I can assure you that unless you happen to have a baby at each breast (and I never did), this experience is inconvenient, frustrating, and downright messy.

Typically, when we say something is a letdown, we are expressing disappointment. I can’t help but assume that this breastfeeding term must have been coined by a woman who experienced the simultaneous letdown that is becoming two. She must have known the paradoxical feeling of release, of holding on and letting go at the very same time.

Lauren Frances Evans, Monument Letdown, 2018, dehydrated breast milk, hydrated lime, and matte medium on paper, 12 × 12 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Before the varied letdowns of motherhood occur, a woman must first bear down. So often labor and birth are depicted as the woman gritting her teeth, pushing with all her body’s force. “Push, Push, PUSSSSHHHHHH,” we hear the nurse chanting, as the new mother struggles with all her might to bring forth her new baby. This bearing down is often depicted as the most intense and difficult stage of labor, one that requires extreme and total effort on the part of the laboring woman.

This, however, was not the case for me. I had been in labor all day, feeling the urge to push for hours but being instructed during every single contraction not to push. My cervix hadn’t fully dilated. We waited hours for that last centimeter, that little lip of flesh, to clear. The most difficult part of my labor was the not pushing. When I was finally given permission to push, I was able to let go and allow my body to take over. The wave of relief I felt on that very first push was unlike anything I’d ever experienced. To bear down, I found, is not only to push but also to release.

In her Guide to Childbirth, famed midwife Ina May Gaskin describes the process of cervical dilation through what she refers to as the “sphincter law.” Gaskin suggests that the cervix must be utterly relaxed in order to open up properly and fully, explaining that “labors that don’t result in a normal birth after a ‘reasonable’ amount of time are often slowed or stalled because of lack of privacy, fear, and stimulation of the wrong part of the laboring woman’s brain.” Her explanations are elaborate and beautiful (and quite critical of common obstetric practices). She stresses that the cervix behaves like a sphincter and that “sphincters cannot be opened at will and do not respond well to commands (such as Push! or Relax!).”4

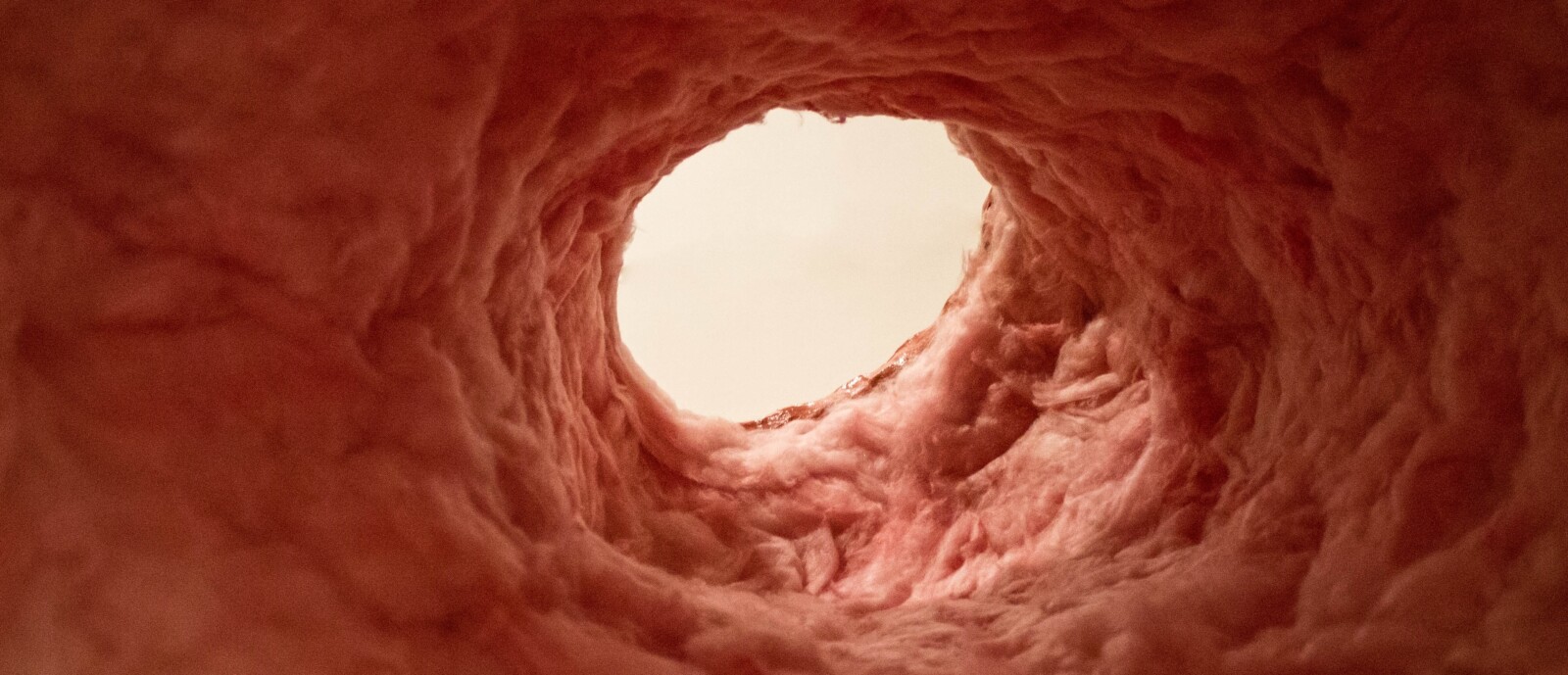

Shortly after the birth of my daughter, I created three collages that I’ve titled Sphincter Law I, II, and III, but I wasn’t explicitly thinking of Gaskin’s sphincter law when I made these pieces. It was only when a pregnant friend asked, “Is that a cervix?” that I realized how much the pieces reminded me of this portal, of the complex and somewhat paradoxical experience of its expansion.

I liken the creative process to the complex, laborious, and life-giving experience of becoming a mother. As a maker, I’m not always conscious of the significance of the work I make until I have the chance to step back and see my image reflected back to me in it. This is a truly mystical unfolding, which I also experience when I catch glimpses of myself in my daughter’s face. And I can only imagine that the creator God must experience something similar in relation to us, God’s creation.

Both roles, artist and mother, are lenses through which I come to better understand and relate to my creator God. But these aren’t simply metaphors for God—each is an embodied knowing, an incarnation. In each role I experience a simultaneous oneness and otherness in relation to God. Just as my child could not have existed apart from me once, I too could not exist separate from the creator God. Just as she bears the mark of our separation in the center of her abdomen, I too feel God’s otherness at the center of my being.

- Jordan, “Placental Thinking,” in Placenta Wit: Mother Stories, Rituals, and Research, ed. Nané Jordan (Bradford, ON: Demeter, 2017), 145.

- See Jordan, “Placental Thinking,” 149.

- Lazarre, The Mother Knot (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1976), 35.

- Gaskin, Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth (New York, NY: Bantam, 2003), 170.