Divided tongues, as of fire, appeared among them, and a tongue rested on each of them. All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages, as the Spirit gave them ability. . . . “In the last days it will be, God declares, that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh, and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams.”

—Acts 2:3–4 and 2:17, NRSV

Tongues of fire, dreams and visions, a holy spirit poured out on the flesh, prophesies of the world to come—in these miracles, the Spirit is given, and the story of Christian salvation is brought to fruition. Pentecost is a kind of Christian repetition of the Jewish festival of Shavuot, which commemorates the giving of the Torah to Moses on Mount Sinai. As the Holy Spirit is poured out at Pentecost, no longer do cultural, ethnic, gendered, sexual, linguistic, or national backgrounds matter to who belongs and who is excluded; in the Spirit we are all one, and all things are new. A wholly new community of interhuman belonging is possible, as “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord shall be saved” (Joel 2:32).

Despite such a hopeful message of unity and belonging, much of Christian history seems to portray the opposite. Instead of producing a vision of community that is open and hospitable to all, the narrative of Pentecost, or the language of the Spirit, has been posed against the flesh of Christianity’s others. Perhaps no group has borne the brunt of this weaponization of the Spirit against the flesh more than the Jewish people. Through the teaching that Christ has freed sinful humanity from the requirements of the Torah, Christian salvation has become associated with the living spirit of grace whereas the flesh has remained tied to the “dead letter” of Jewish law.1 In this equation, Christian spirit comes to signify the transcendent and nonbodily reality of redemption whereas the flesh is a kind of worldly remainder of humanity’s fallen and law-bound condition of sin.

Such a spirit-centered gospel has typically privileged an otherworldly notion of salvation over material struggles for earthly liberation. And more troublingly, it has provided a foundation for anti-Jewish, anti-Semitic, and colonial Christian supremacism and violence that demonizes and subordinates Jews and other non-Christian peoples (i.e., those who have refused the universalism of Christian truth) precisely as those who lack the Spirit and are therefore stuck in the fallen condition of the flesh. In this anti-Jewish formula, the flesh and the Jewish law kills while the spirit of Christianity gives life.2

If we are to avoid this anti-Jewish and anti-flesh reading of Pentecost, which is imperative for any antiracist, life-affirming, and justice-oriented Christian theology, and if we are to contemplate what it might mean to be of the kind of Spirit that Acts is describing while also remaining committed to the fact of our flesh, we must rethink what it is we mean by both flesh and spirit. If our true being and life is found in our shared flesh, that is, our common capacity to be with and touch one another, to eat and drink with one another, to be at risk with one another, to care for one another through medicine, friendship, and love, to live and die together on earth in all of our fleshly differences, frailties, and vulnerabilities—if we are to contemplate what it means to be of the Spirit in a way that stays true to the fact that we are, together, creatures of the flesh—we need a new theological imagination.3

The American modernist poet Wallace Stevens knew something about imagination, and while it might at first seem a wild stretch, I think we can link Stevens to the message of Pentecost. For Stevens, the imagination is the only thing that is truly real, the only path through which we can possibly cope with the unbearable order of a modern world arranged precisely to make us forget the fact of our flesh and to prevent us from ever questioning what Stevens calls the “doctrine” of the world, its status quos and unquestioned truths. We “[escape] from the truth,” he says in “The Latest Freed Man,” by poetically imagining a different world in which “the morning is color and mist, / which is enough . . . He bathes in the mist / Like a man without a doctrine.” Against our experience of the given order of this world, poetry allows us to conceive a wholly different reality; it “help[s] people live their lives” as it enables them to live in the possibilities of the flesh.4

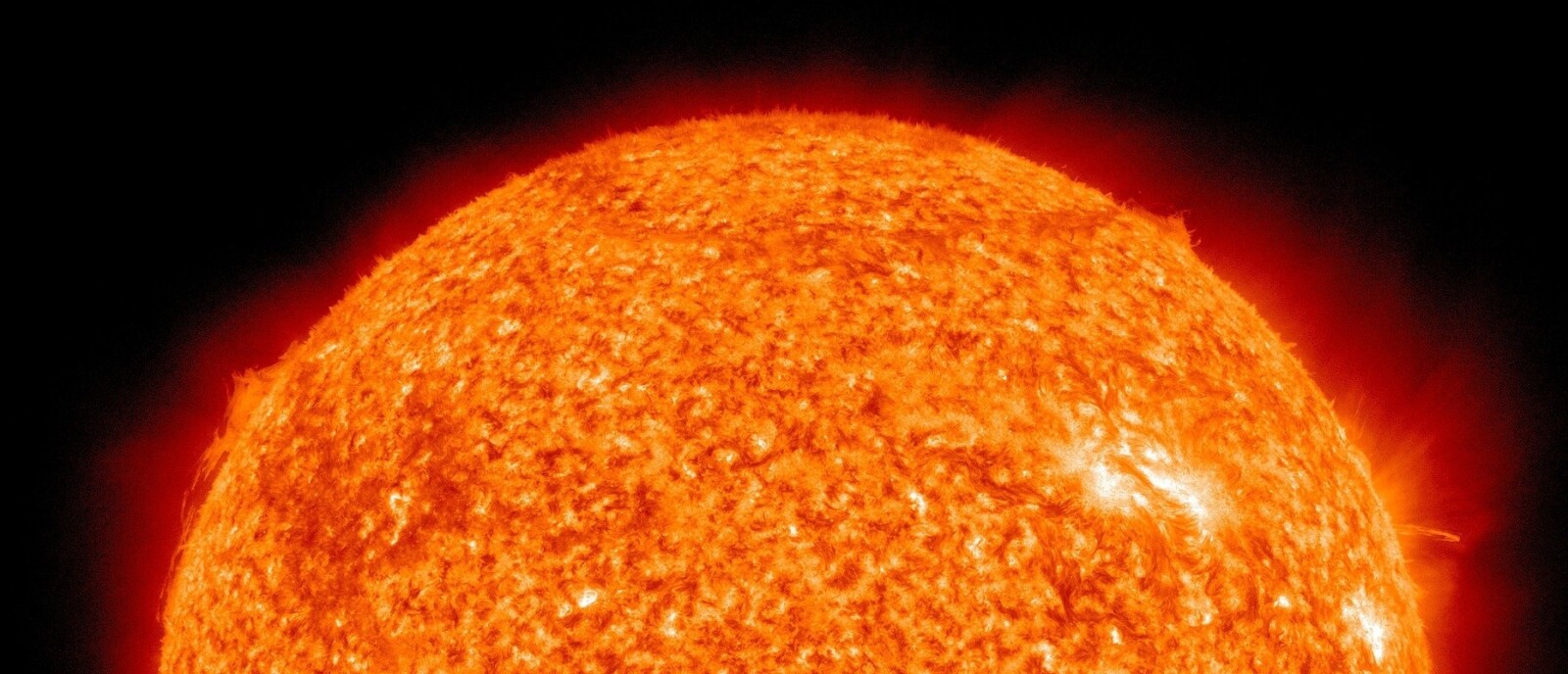

Take the sun, for example. References to the sun abound in Stevens’s poetry, usually signifying the inconceivable source of all things, the condition of our very existence, or the idea of an unmediated and divine reality beyond the limitations of language, culture, and the doctrines of the world. The sun is “a new knowledge of reality,” or it is that which calls us “to be without a description of to be.” As he imagines in “Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction,” “How clean the sun when seen in its idea / Washed in the remotest cleanliness of a heaven / That has expelled us and our images.” Herein lies what I might call the Pentecostal Wallace Stevens. Like the sun that is given from beyond, the Spirit pours out upon us the gift of possibility itself. But also like the sun, the giving of the Spirit as it’s described in Acts can only be felt and experienced from our specific locations, in our particular languages, in our particular fleshly bodies, and, as Stevens will insist, through our particular imaginations.

The Spirit, God, the sun, the sheer fact of our flesh—whatever you call it—is that which cannot be grasped. It has no name; it is unthinkable; it “expels us and our images.”5 Here is the indescribable and ungraspable miracle of our very existence. Any attempt to bring the wonder and beauty of our common existence—the fact of our flesh—into our own descriptive realms and doctrines can only be an act of domestication and idolatry. And yet, we must think it, we must imagine it, we must name it—“gold flourisher”—and embrace the fact that this miracle can only be given and experienced in our shared flesh, in “the difficulty of what it is to be.”6

The Spirit calls us to embrace the fact that we are flesh, that we are embodied and limited, and that we can imagine the presence of God only from our own finite and particular locations. In the message of Pentecost, we are unified not by a spirit that makes us all the same, that allows us to claim some universal, transcendent, and singular truth of “Christian identity,” but rather by an enfleshed imagination illuminating the sheer miracle of each and every person, each and every form of being human, each and every difference that makes the world an inexhaustible place of enfleshed wonder and mystery.

As Luke wrote in the book of Acts, receiving and living into the imaginative spirit that illumines and embraces the common condition of our shared flesh, which cries out for justice and belonging, will make you appear crazy:

Amazed and astonished, they asked, “Are not all these who are speaking Galileans? And how is it that we hear, each of us, in our own native language? Parthians, Medes, Elamites, and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabs—in our own languages we hear them speaking about God’s deeds of power.” All were amazed and perplexed, saying to one another, “What does this mean?” But others sneered and said, “They are filled with new wine” (Acts 2:7–13).

From the perspective of those who are invested in containing and policing the flesh, of forcing all human difference, desire, and belonging into a violently controlled and hierarchized world of nationalist, capitalist, patriarchal, White supremacist, and anti-Black order, this is inebriation. The order of this world operates around a profoundly impoverished imagination that cannot conceive of the possibility of different forms of enfleshed life beyond economic transaction, political calculation, and White normativity.

The weeks following George Floyd’s murder in the United States have intensely shown how powerful and entrenched this order remains. George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor. We must say their names because they are of our shared flesh. We must carry their memory and spirit within our flesh as we imagine a justice to which each and every one of us is called. The death of each and every Black person in the United States by the violence of the White supremacist order is a high crime against the flesh upon which the Spirit is poured out.7 State violence against Black people is violence against all of us; it is blasphemy against the Spirit.

The uprisings in Minneapolis and elsewhere in response to police brutality are not spontaneous events, even if they seem so to some of us. Rather, they are the welling up and overflowing of a deeply cultivated and uncontainable imagination of and longing for a justice that, despite the sustained and deep organizing of other forms of protest that have long preceded these particular uprisings, seems never to arrive in America. For a lot of us, especially White people, these events are difficult to comprehend. For a lot of us, our first instinct is to recoil from the messy and violent acts of property damage and fires. “They must be drunk,” we are tempted to say. But the Spirit moves in unpredictable and undomesticated ways—it refuses every demand to remain contained within our White doctrines, it “expels us and our images.”

Like these uprisings, perhaps the event of Pentecost in Acts was not spontaneous either. Perhaps the outpouring of the Spirit on Jesus’s disciples was also an overflowing of something that had always been there, present in the flesh of Jesus and all others moving and living through the imagination of an inconceivable justice to come. It was there in Jesus’s refusal to play by the doctrines of the world as he ate with sinners and befriended prostitutes; it was there in his riotous upheaval of a temple turned market; it was there at his crucifixion by the Romans, like the crucifixion of George Floyd by the Minneapolis police, a death that in the imagination of resurrection is refused and resisted; and it was there at Pentecost when it burst open toward the production of a new life of interhuman belonging that simply could not wait any longer.

As we process the events following the murder of George Floyd, I suggest that we imagine a kind of Pentecostal and poetic irruption of the Spirit grounded in the fleshly traditions of the oppressed. We might think of the giving of the Spirit as that perpetual uprising of the flesh that has been and continues to move in uncontainable and unwieldy desire against the order of US state violence. Like the sun that bears no name, tongue of fire, all things are illumined and possible. We stand in flesh and spirit awaiting justice for Floyd and all others crucified by an antiflesh and anti-Black world. May we have the imagination to make it so.

- Jeffrey Librett, “From the Sacrifice of the Letter to the Voice of Testimony: Giorgio Agamben’s Fulfillment of Metaphysics,” Diacritics 37, no. 2–3 (2007): 15.

- Librett, “From the Sacrifice,” 17.

- On the theme of the flesh, see Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (1987); Alexander Wehilye, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014); Mayra Rivera, Poetics of the Flesh (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015); and Roberto Esposito, Immunitas: The Protection and Negation of Life (Malden, MA: Polity, 2011).

- Stevens, “The Latest Freed Man,” in The Collected Poems (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1990), 204–5; and Stevens, “The Noble Rider and the Sound of Words,” in The Necessary Angel: Essays on Reality and the Imagination (New York, NY: Random House, 1951), 29.

- Stevens, “Not Ideas about the Thing but the Thing Itself,” in The Collected Poems, 534; “The Latest Freed Man,” 205; and “Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction,” in The Collected Poems, 381.

- Stevens, “Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction,” 381.

- See Spillers, “Mama’s Baby,” 67.