Tomorrow, after one of the longest years of any of our lives, we will (thankfully) celebrate Christmas. I, for one, am more than ready for it.

One of my favorite Christmas choral pieces for the season is “O Magnum Mysterium” by the American composer Morten Lauridsen. I return to it several times a year around this time, for it speaks to me of the entire mystery and beauty of our story:

O great mystery,

and wonderful sacrament,

that animals should see the newborn Lord,

lying in a manger!

Blessed is the virgin whose womb

was worthy to bear

the Lord, Jesus Christ.

Alleluia!

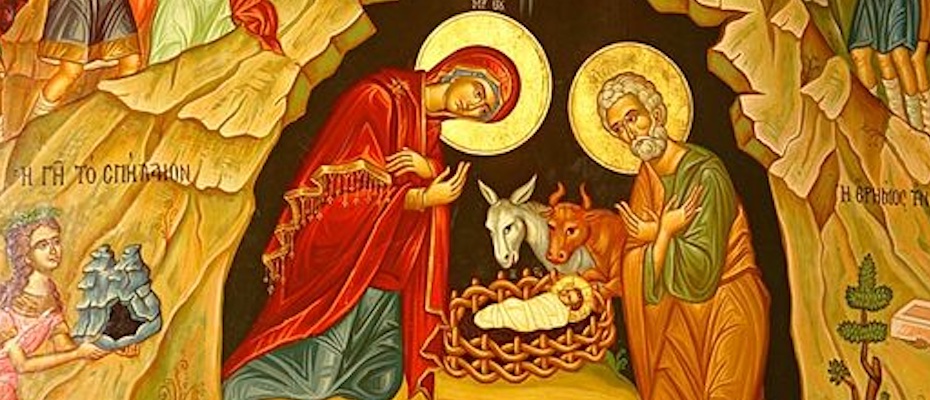

But it’s not just this mystery that captures my imagination. It’s the wild incongruity of it— “that animals should see the newborn Lord, lying in a manger.” Imagine it: the ox and the donkey, created and ever held in being by the Almighty, now look down upon their God, present not just in but as human flesh—helpless, vulnerable, and weak. Stop and ponder: the virgin whose womb was fashioned by the hand of God now bears God, even as God ever and always bore and bears her still to the very end of time. And if the gospel is true, then we are to believe that it is precisely by this wild incongruity that the world is saved.

Just what kind of a God would tell a story like this?

“O Magnum Mysterium” ends, as it surely must, with an alleluia. We fall down in worship and gratitude, as we should. But in between my own allelulias, as often as not, I find myself smiling, even laughing at the wonder of it all. And this laughter, I think, is a mode and manifestation of the great universal alleluia. It is a sign of the kingdom.

The theme of laughter, of course, is everywhere in the Scriptures. Laughter is, indeed, a regular response to the goodness of the Lord. The psalmist wrote the following:

When the Lord restored the fortunes of Zion, we were like those who dreamed. Our mouths were filled with laughter, our tongues with songs of joy. Then it was said among the nations, “The Lord has done great things for them.” The Lord has done great things for us, and we are filled with joy. (Ps. 126:1–3 NIV)

For all the flaws in the advice of Job’s friends, this promise proved true: “He will yet fill your mouth with laughter and your lips with shouts of joy”(Job 8:21). Jesus himself made laughter a sign of the kingdom’s arrival: “Blessed are you who weep now, for you will laugh” (Luke 6:21).

And of course, who can forget the story of Abraham and Sarah, who upon being told that they, even they, in their old age would bear a child, laugh at the wonder and absurdity of it, only to discover that this promise also is true, and thus they name the child Isaac, which means “he laughs.” As Sarah says, “God has brought me laughter, and everyone who hears about this will laugh with me.” I can imagine her chuckling with wonder. “Who would have said to Abraham that Sarah would nurse children?” she continues. “Yet I have borne him a son in his old age” (Gen. 21:6–7).

Who indeed would say such a thing? Who could say such a thing, and both mean it and bring it to pass? Only God. And so Sarah laughs and laughs, and Abraham laughs with her, and now we also laugh with them at the surprise and wonder of the goodness of God who out of bodies as good as dead (Rom. 4:19) knit together a son, Isaac, in the once barren womb, the son who is a living laughter and whose own life will forever serve as a figure of that other Son who was and is and ever shall be Laughter Incarnate.

What is it, I wonder, about our laughter that makes it a sign of the kingdom?

The question was driven home to me recently in conversation with a friend who went through an absolutely awful time last year. I had walked closely with him through an unfolding process that for a season looked like one of the most remarkable and best things that had ever or would ever happen to him—a life-defining opportunity—only to see it sour in the worst possible way at the last possible moment.

The experience left my friend eviscerated. It felt like a cruel joke, not just to my friend, but to all of us who watched it happen. The ironies in the story were, and are, everywhere.

But here’s the curious thing—as we recently looked back upon the year and talked about those ironies, it became clear that for him the experience and perception of those events are changing. Where once they felt only cruel—fantastically cruel, spectacularly cruel—now, as the Lord is growing redemption after this scorched-earth experience, so also the first ever-so-delicate sprouts of genuine laughter are beginning to push through the dark soil of the loss.

How is that so? The late Robert Jenson provides an answer that at once suggests the wonder of the gospel and the peculiar joy of being creatures made in the image and likeness of God. In a daring essay written toward the end of his life, Jenson argues that humor is at the very heart of personhood and that it is divine no less than human. Without humor, he says, we simply do not have a person at all. “A sheer moral subjectivity is not yet personal,” Jenson claims. “To say that there is a moral intention at the ground of things is not yet to speak of what the Scriptures call God. . . . A person is a moral subjectivity with a sense of humor. If God, therefore, is personal, he is not only the moral intention at the ground of things. He is also the laughter at the ground of things. The sense of humor at the ground of things.”1

But if it is the case that personhood entails humor, “must not the subjectivity that hates all things [that is, the devil] have also its humor, and therefore be understood as person?” Indeed, for Jenson, the truth of the claim is proved by our experience: “For surely it seems that evil not only impedes and derails good intention, but mocks it.” Someone, he suggests, “is having malicious fun with God’s creation.”2

It certainly seems that way. Life under the sun, for all its joy, is also replete with what feels like cruel mockeries. This year has seen more than its fair share of them. I am thinking of the business owners who willingly closed their doors to help their communities during the pandemic only to see them finally washed away by economic realities they couldn’t control. Or the marriages and families that broke under the weight—of all things—of being forced to spend more time together. Or the health-care workers whose own physical and mental health took a pounding in their efforts to help others. Or the Black Americans in our country who felt either abandoned or, worse, opposed and resisted by those who, by virtue of their creed, ought to have known better, white Christians. In these and countless other examples, it seems as though the joke is on us. The ironies are cruel ironies.

And that, for Jenson, gets right to the heart of the matter. Why is it that the devil feels the need to laugh at us, to mock us? It would seem that, given the devil’s propensity to his own kind of humor, he, by Jenson’s own definition, also is “person.” But there is a difference between the devil’s humor and God’s. Jenson explains that “the devil’s humor is always mere wit; he is never truly funny,” for “the devil’s jokes are never on himself.”3

The spinning of malicious ironies and cruel jests at the expense of others is not yet humor—and therefore it is not yet an evidence of true personhood. It is, rather, evidence of a great deficiency at the core of the devil’s being. His personhood, if it can be spoken of using that term, is a negative personhood, as the great tradition has (almost) always and everywhere affirmed:

Thus the devil is indeed a person, but a sort of negative, mirror-image person. He is a parasite-person: the laughter which constitutes him as person is always on someone else. He never sees the joke on himself, as God does and as we sometimes do. The devil is personal only in the passion of his refusal to be a person. The devil’s jokes are never on himself because he has no self for them to be on.4

This point is worth lingering over. It is the difference, we might say, of being the butt of a practical joke and being bamboozled for our own good.

When my wife turned twenty-one, I threw her a surprise birthday party. I was secretive in my planning, and she suspected nothing. We had a lovely dinner together and then went off to the apartment of some friends for what she thought was going to be a small, intimate gathering over cake and ice cream. It turned out to be quite nearly allof our friends. I’ll never forget the expression on her face when we walked through the door to a mob shouting “surprise!” and “happy birthday!”—she laughed and laughed and laughed, as we all did, with her. And then we settled in for a delightful evening. The joke was on her—for her good and for ours. We shared in the bounty of the jest together.

It takes persons to be able to do that, both to enact and to receive genuine good humor. And because God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—is supremely personal, God can do both. Indeed, perhaps the most surprising part of Jenson’s essay is his claim that God “always sees the joke on himself.” In his triune being, God makes himself objective to himself and so God can look upon God and laugh. And in the economy of salvation, God makes God objective to us as the incarnate Christ, “the body on the cross and the body on the altar,” and God reigns neither in empty, malicious wit nor in brute power but in communion, shared fellowship and joy.5 Jenson explains:

On that cross and on that altar, the joke can be on God . . . I too can see the joke on myself . . . I can let myself be your object. I can let you have your view of me. . . . And then I can take that Jenson as you see him, and find myself therein. Whereupon we must all, of course, burst out laughing. And indeed, only as I do this, only as I let the joke be on me, do I at all have, like God, a self, an object in which to find myself. What ails the devil is that he will not give himself over to be anyone else’s object. He will not allow himself to be defined by anyone else’s gaze. . . . He can never see the joke; he can only make cracks about others.6

The devil mocks us with his malicious ironies because he cannot see the good humor, the wild incongruity, of all that God does.

That God spins a universe as vast and old as ours only to focus his efforts on one tiny planet and one very small sliver of time in its history is funny, if we have eyes to see it. That God calls the feeblest and most awkward of mammals—us—to share in his reign is funny, if we have eyes to see it. That God appoints beings much more powerful than us to be our servants is funny, if we have eyes to see it. And that God determines from all eternity to become one of us, to wash our feet and share our fate, to serve us and lift us into his everlasting life, well, that also is funny, if we have eyes to see it. These examples are funny in the way that only grace can be funny, in the way that all good surprises are funny, in that peculiarly personalizing way that is characteristic of the gospel, where no one has to lose and everyone can share in the great good fun.

The devil’s problem is that he refuses to see the jest and to thereby share in its blessing, and therefore, he is reduced to a kind of counterfeit humor, weaving wicked ironies to spite God and ruin us. What, after all, could be more wickedly ironic than so spoiling the minds of God’s creatures that when Jesus came in the flesh with no intention other than to heal and save and dwell with them, in fear and envy they killed their maker?

But such is the genius of our God, that he inhabits even that, the cruelest and most malicious of jests, subverting it with his goodness so that it finally becomes an everlasting cause of our wonder, our praise, our laughter.

God has a sense of humor. An excellent one. God knows how to have a good laugh, the kind of laugh that is at no one’s expense, that widens and widens as a circle of joy so that all who will may enter into the laughter of the Lord. Frederick Buechner was surely right when he said that “it is only when you hear the Gospel as a wild and marvelous joke that you really hear it at all. . . . Heard as anything else, the Gospel is the church’s thing, the preacher’s thing, the lecturer’s thing. Heard as a joke—high and unbidden and ringing with laughter—it can only be God’s thing.”7

And that is the hope for our lives, that in Christ Jesus, that True and Better Isaac, God’s Laughter Incarnate, every cruel and malicious irony that has ever been hurled at us will finally be taken into God, saturated with his good pleasure, and turned to our benefit so that when all is said and done, between grateful sobs, we’ll laugh with God like fools, and we’ll keep on laughing, right into the kingdom where our joy will know no end.

- Jenson, “Evil as Person” in Theology as Revisionary Metaphysics: Essays on God and Creation, ed. Stephen John Wright (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2014): 137.

- Jenson, “Evil,” 139.

- Jenson, “Evil,” 140.

- Jenson, “Evil,” 140.

- Jenson, “Evil,” 140.

- Jenson, “Evil,” 140–41.

- Buechner, Telling the Truth (San Francisco, CA: Harper, 1977), 68.