The first time Paul Martindell brought his new wife, Lauren, to Bill’s Ford—they were in their early forties, a second marriage for both—she said she thought she was being taken to an automobile dealership. But one look at the little town in the Ouachita Mountains and she proclaimed it “cute” and the little house Paul had grown up in “not as bad as I thought it’d be.”

The left-handed compliment was mostly Paul’s fault. He had a habit of dramatizing his upbringing in backwoods Arkansas for his friends and colleagues in Naperville, the Chicago suburb where he and Lauren lived, hinting that he’d grown up without the benefit of electricity, running barefoot to the outhouse when nature called. In fact, his father had been the principal and basketball coach at Bill’s Ford High, and though their house was hardly a palace, they did indeed having running water and a window air conditioner in the living room, which, if they turned it up all the way, would cool the entire house except for the back bedroom shared by Paul and his younger brother, Shelby. It was Shelby’s house now, and when Paul and Lauren came back to Bill’s Ford on the occasion of Aunt Doris’s dying, they stayed in that back bedroom, which, fortunately, had its own window air conditioner now. Paul could swear it was the same one that had been in the living room when he was a boy.

“The same one? Ha, are you crazy? That thing would have to be fifty years old,” Shelby said, squatting down and fiddling with the controls.

“So? They made things better back then,” Paul said.

“Some things. Not electronics. Everything electric is better today. Cars, too. Everything about cars is better by a mile. Not everything gets worse, my friend. Men can make things better when they set their minds to it.”

“Slow down now, Shelby. You sound like you’re getting ready to break into a sermon.”

Shelby was the preacher at the Rock of Ages Baptist Church in Bill’s Ford. He’d left town just long enough to go to the seminary in Memphis and then returned to take over when Reverend Vaught retired. Paul had left for college, too, but hadn’t come back. He’d known as soon as he was old enough to dream something other than being a cowboy or fireman that Bill’s Ford wasn’t part of his dream.

“This thing was working yesterday,” Shelby muttered. Then: “Oops! Wasn’t plugged in. Deb must have unplugged it so she could vacuum this morning.”

Right on cue, Deb, Shelby’s wife, came into the bedroom and told Shelby to get out of Paul and Lauren’s hair so they could get settled in before supper. He left them, and Paul put their suitcase up on the bed and then stepped back as Lauren took over, transferring clothes into the chest of drawers. Halfway through, she stopped and looked around her like all this was a bad dream. It’d been a long time since she’d thought Bill’s Ford was cute.

“I don’t know what we’re doing here,” she said, “I really don’t. Can you tell me what we’re doing here, Paul?”

She was glaring at him. He tried to look her in the eye.

“You know what we’re doing here.”

“Do I? Is she dead? Is the old bitch dead?”

“Shh.”

“Don’t shush me! Don’t you dare shush me! I just want to know when she’s going to die.”

“She told Shelby she’d die in the spring. Tomorrow’s the last day of spring. I told you all this.”

“Yeah, you told me all this, and I still don’t believe what I’m hearing.”

Paul wasn’t sure he believed it, either. All he knew was, if they drove all the way down from Naperville and Aunt Doris didn’t die, Lord have mercy.

Deb made a chicken and broccoli casserole for dinner and served it with an iceberg lettuce salad. Paul was relieved to see that Lauren thought it was pretty good—or at least edible.

Paul hadn’t grown up eating cornbread and greens with pot liquor like he tried to make the folks at the law firm in Naperville believe, but when Lauren made that first visit to Bill’s Ford, Aunt Doris cooked fried ham and red-eye gravy for supper along with canned green beans boiled limp with the hambone and a tablespoon of sugar. Lauren tried to eat it, but the ulcer she’d been fighting off most of her adult life was outraged by the grease. “What’s the matter, don’t she eat pork? Is she Jewish or something?” Aunt Doris had asked Paul as if Lauren weren’t sitting right there, and Paul had replied, “No, Catholic,” which was worse. There wasn’t a single Catholic church in the county.

Paul and Shelby’s mother had died when the boys were still in grade school, and Aunt Doris, their father’s sister, had moved in to help. In fact, she basically took over because their father wasn’t worth much after his wife died. He lasted only three more years before following her to the grave. Paul never was clear on what had killed him. “He died because he wanted to die,” Shelby said years later, and then when he saw the look on Paul’s face, went on, “No, not suicide. He just didn’t want to live any more. Just quit living. I pray for him every day.” Shelby believed, Paul suspected, that his prayers were all that kept their father’s despairing soul from the flames.

At supper, Paul and Shelby told Aunt Doris stories, as if she were already dead. They’d have smiles on their faces when they told them, and you might have expected them to laugh because that’s what we do when we fondly recall the beloved dead—we smile, we laugh. But there was no laughter. Aunt Doris had been fierce in her protectiveness, her watchfulness, fierce in her rectitude and demand for rectitude, but she had not been funny.

Shelby brought it to a close by saying, “Well, she kept the family together. She made a home for us, and I’ll always be grateful for that. Right, Paul?”

“If you say so.”

“I do say so,” Shelby said, flaring up.

Shelby had always had a quick temper but was as quickly contrite. Paul tried to think if he’d ever lost his temper. Aggravated, yes, aggravation was the sea he swam in.

Shelby went into his study to work on his sermon, and Deb and Lauren began to clean up the kitchen. Paul headed for the living room and that La-Z-Boy.

He’d no sooner dropped off to sleep than Shelby came out of his office and said, “So, I guess you’ll be wanting to see Aunt Doris tonight.”

“Will I?” Paul said.

They left Deb and Lauren sitting at the kitchen table gabbing like best friends. Paul was a little charmed and a little surprised. He’d never thought of Lauren as a gabber, especially not with Deb, a large, slow-moving woman with thick ankles and manlike hands who, as far as Paul knew, had never been out of Arkansas in her life. A few years ago, she’d spent a night at the Med Center in Little Rock—some woman thing—and came back reporting that she’d been scared the whole time, not because of the medical procedure but because “They had me all the way up on the fourth floor.” How Lauren, a Chicago girl, had laughed.

The clinic in Arkadelphia (Bill’s Ford didn’t even have a drugstore) was tiny, an L with offices and exam rooms down one side and a few patient rooms down the other. Except for two nurses at the reception desk, the place seemed deserted.

Shelby turned into the second door on the right, and Paul followed him in. And there she was. Paul took a step back, stunned. It was as if he’d heard part of a story and was going in to hear the other part, but instead of a story he’d come face to face with the thing itself.

“They’ve amputated her legs,” Paul said.

Shelby looked at him like he had two heads. “What?”

Paul shook his head. “No . . . it’s . . . nothing. Sorry.”

Aunt Doris looked so tiny, her almost hairless head sunk into the huge pillow, sheet pulled taut across her absurdly short torso—legless he’d thought in his shock, his disorientation.

Her eyes were red slits. They seemed to be directed—sightlessly—toward the TV that perched mute and blank on its wall rack.

“Is she still alive?” Paul asked, feeling foolish, but he didn’t know. He couldn’t tell.

“Just,” Shelby said. He walked around the bed so that he wasn’t between her and Paul—he’d always been the considerate brother—and patted the sheet where, Paul supposed, Aunt Doris’s hand was.

“Hello, Aunt Doris. Hello, sweetheart. Guess who’s here? It’s Paul.”

Sweetheart. He’d called Aunt Doris sweetheart.

“What’s her condition? I mean, what exactly is her problem?”

“Years,” Shelby said. “Too many of them.”

Then Shelby said, “Come on over where she can see you.”

Paul stepped over to the foot of the bed. He looked down at Aunt Doris, and it seemed that she was peering right at him. But then he realized that he was standing between her and the silent TV. He sidled a couple of steps to the right. The eyes followed him.

Startled, Paul gasped, “Jesus!”

“Jesus.”

Had she said that? Jesus. Had Aunt Doris really said that? Paul looked at Shelby. Shelby nodded toward Aunt Doris.

“Go on,” he said. “I think she wants to talk to you.”

“Me?”

“Go on.”

Paul edged around the bed. He bent down over the old woman. “Aunt Doris?” he whispered. Then he put his ear to her mouth.

“Jesus will spew you out. You are lukewarm.”

Paul jerked back. Did you, he began to say to Shelby—Did you hear that?—but Shelby had to have heard her. She had spoken the words with ferocious clarity. He looked at those eyes staring back at him, red slits with a black dot the size of a BB in each.

“Aunt Doris,” he said, his voice breaking. Then he tried to say her name again but only managed a sob like a heartbroken little boy and fled the room.

He sat on a bench in the hall. A nurse came up the hall and went into Aunt Doris’s room. A few minutes later Shelby came out and sat next to Paul.

Paul was embarrassed—that sob. When they were boys, Shelby had been the emotional one, short-tempered but sensitive, crying easily. You couldn’t make Paul cry. He prided himself on it.

“I’m sorry. I don’t know what got into me in there,” he said.

Shelby patted him on the knee. “That’s okay. It’s only natural,” he said, and then, almost as an afterthought: “She died.”

“Oh.”

Shelby squeezed his knee. “Do you want to pray?”

“You’d better save that for Aunt Doris,” Paul said.

“I prayed for her in the room. But you don’t have to if you don’t want to.”

They went out to Shelby’s car. Before he had a chance to start it up, Paul said, “Why did she hate me so?”

Shelby looked at him in surprise. “Hate you? Where did you get that idea? She loved you. We were her children. She never had anything—anybody—else.”

Aunt Doris had never married. She’d lived with her parents—Paul and Shelby’s paternal grandparents—on the family farm until both were dead and then stayed on, running the farm with hired hands until her brother asked her to come to town and help with the boys.

“She seemed about as loving and maternal as a pickax to me,” Paul said, and when Shelby started to respond, he went on, “I don’t know what she had against me. No, don’t bother to deny it. I always fell short in her eyes. But I’m not really such a terrible guy, you know.”

“I never said—”

“No, I know you didn’t, but I know what some people think. But I do try. I really do. Hey, I’ve got friends. And there are people who’ve loved me. Two women loved me enough to marry me. I just really don’t know why it never seems to pan out.”

“You need to work real hard on this one. That Lauren is a keeper.”

“Preaching to the choir, little bro. And you’re right. This one just has to work out. I don’t want to be a three-time loser.”

“Three? You’ve only been married twice.”

“I know, but I’m adding on the one after this.”

He laughed at his own joke, but Shelby didn’t see the humor.

Paul shrugged and said, “I really do wish I knew what my problem is.”

“The trouble with you isn’t problems. The trouble with you is you don’t have solutions.”

“What, are we talking in koans now?”

“Cones? I don’t know about any cones. All I’m saying is you’ve got to have something to lean on when it gets too tough for you to take on alone.”

“What do you have?”

“I’m the luckiest guy in the world. I have two things, God and Deb.”

“Right. But when have you ever faced the toughest going? When it got too much for you? Not when Mama and Daddy died. You did OK on your own then.”

“I prayed. Besides, I had you then. And Aunt Doris.”

“And since then? It’s been mostly smooth sailing for you, hasn’t it?”

Shelby turned away, looked out the window at the darkness.

“It hasn’t always been smooth sailing. Deb and I . . . there was a bad time right after the kids were grown and out on their own. There was . . . infidelity.”’

Paul was thunderstruck, speechless.

“If I’d lost Deb, I don’t know what I would have done. I thank God I still have her.”

“Was it hard to forgive her?”

Shelby turned back to him with a look of consternation, as if Paul had uttered a blasphemy.

“It wasn’t Deb who was unfaithful,” he said.

“You don’t mean—”

“Why not? There’s only been one perfect man, and they nailed him to a cross.”

“I never thought you were a perfect man, but I always thought you were a good man,” Paul said, then added, “I still do.”

“Not good enough,” Shelby said, and Paul said, “Who is? But tell me, how did you get Deb to forgive you?”

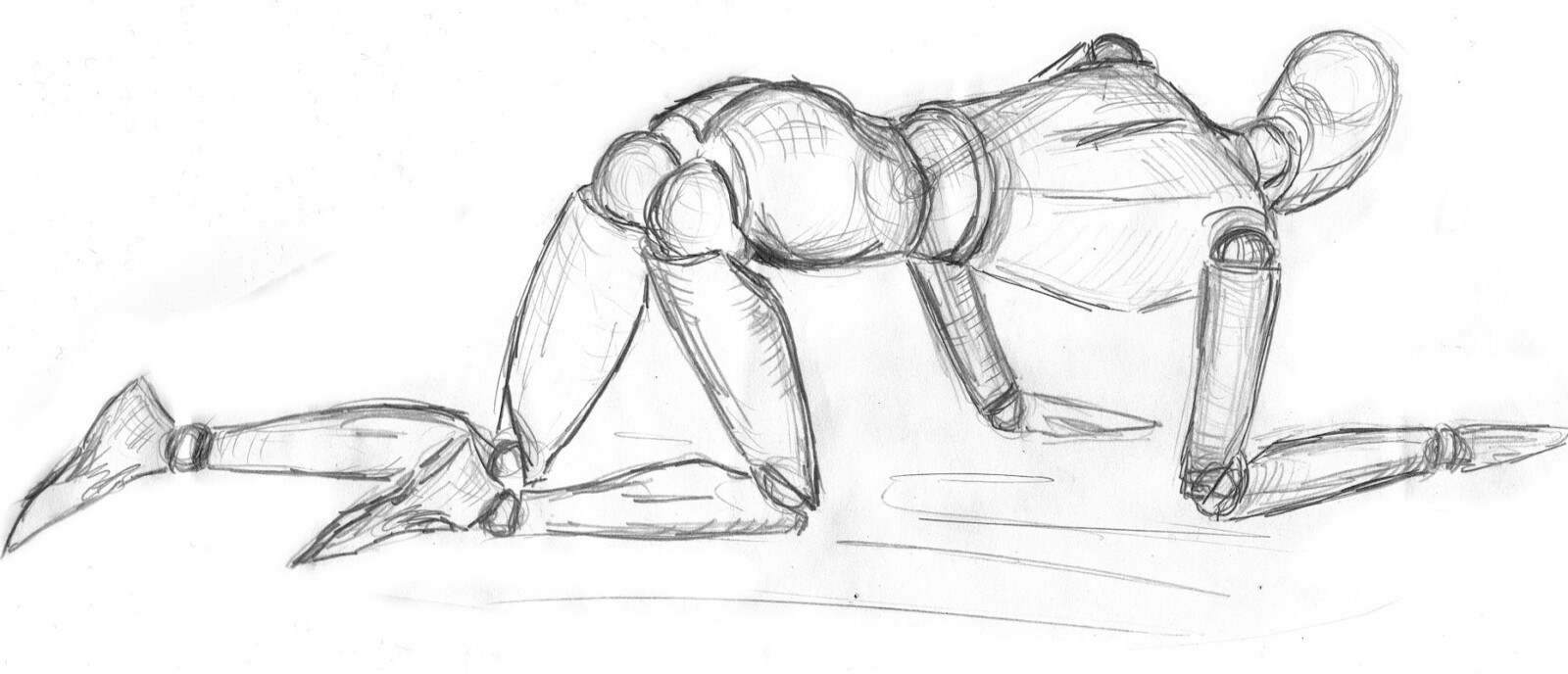

“I got down on my knees and begged her. And she forgave me.”

Paul was taken aback by the image of Shelby down on the floor imploring that stolid, thick-ankled woman. He tried to laugh it off. “Maybe I should have tried that with Jerri,” he said, referring to his first wife.

“Were you unfaithful, too?”

“Never. Not with Jerri or Lauren. Really, I don’t know what I’ve done wrong.”

“Maybe it’s what you haven’t done right. Either way, asking for forgiveness can’t hurt. Why don’t you give it a try?”

“Here now, you done left off preachin’ and taken up meddlin’,” Paul said in his best hillbilly accent.

“No, the preaching starts at the funeral,” Shelby said.

That was a Tuesday, and the funeral was on Thursday. There wasn’t any reason to delay things. No mourners would be coming from any distance.

Shelby and Deb’s kids, Buddy and Melissa, and their families were due to arrive sometime Wednesday. Buddy had a son and daughter and Melissa, a daughter with something wrong with her—Paul couldn’t remember what, some birth defect. At age three she could barely walk and had never talked. Were they all intending to stay there, in Shelby’s house? Surely not.

After breakfast Wednesday morning, Paul found Shelby in his office and said, “Hey, I think Lauren and I better go to a motel in Arkadelphia tonight. With your kids coming, you’re going to have more than you can handle here.”

“No, heck no, Paul. We’ve got it all planned out. You and Lauren will stay right where you are. Melissa and Jack and Clare will stay in Aunt Doris’s room, and Buddy and his bunch will take our bedroom. Deb and I will sleep on the pull-out in the living room. We’ll have a big ol’ time.”

Paul edged a little closer to Shelby and, lowering his voice, said, “I think we better go to a motel. It’s Lauren. Thing is, well, too many people who she doesn’t know very well, doesn’t feel that comfortable around, I just think she’d do better at a motel. She told me, in fact.”

Shelby gave Paul a funny look. Then Paul realized he wasn’t looking at him at all but just past him. He turned and there was Lauren standing in the doorway.

“You son of a bitch,” she said.

“Hey, I—”

But Lauren turned and walked away, saying over her shoulder, “Stay away from me.”

Paul turned back to Shelby and shrugged helplessly. Shelby looked down at his desk.

Paul spent the rest of the morning trying to avoid Lauren, which wasn’t hard because Lauren seemed quite happy to avoid him, too.

By noon, Melissa and Buddy and their families had arrived. Too many people, too much talking—Paul left after lunch and walked up and down the streets of Bill’s Ford. He didn’t run into a soul he remembered. As he was heading back to the house, he decided he should apologize to Lauren. It took the rest of the afternoon—it wasn’t until after dinner, in fact—for him to decide what to say, not an apology so much as a way to turn the thing to his advantage. He’d say that, true, he was the one who’d wanted to go to a motel, but it was because, heh heh, a motel, you see, add a little spice to their marriage, a motel, heh heh, get it?

He went searching for Lauren. She wasn’t in the kitchen with the other women or in their bedroom. As he was walking back up the hallway toward the living room, he just happened to glance into Aunt Doris’s old room, and there she was, kneeling on the floor with her arms around the little girl—what was her name?—Melissa and Jack’s little girl, the one with something wrong with her. Lauren had her back to him, but he could see the little girl’s face over her shoulder. She was crying soundlessly. Lauren was stroking her hair, patting her back. Paul thought he could hear Lauren almost purring like a mother cat. She wasn’t a mother, though. Lauren had no children with her first husband, and Paul hadn’t even broached the subject of children. They’d been in their forties by then, after all. Too old for that stuff.

Somehow the story about wanting to go to a motel with Lauren to—heh heh, you know—no longer seemed like such a good idea.

That night when Paul went to bed, Lauren was already there, sleeping or pretending to sleep.

He got up late the next morning, groggy and disoriented, the effects of the flask of bourbon he’d sneak drinks of the previous evening until nothing was left. Lauren was already up. He went into the kitchen, thinking she might be having breakfast, but she wasn’t there. When he couldn’t find her anywhere else in the house, either, he wandered outside and saw that their car was gone. He went back into the bedroom and found Lauren’s clothes still in the chest of drawers, but her purse was gone. Then he knew. She had left. Fled with just her purse. Fled him.

He went back into the kitchen to eat breakfast but could manage only a cup of coffee. Shelby came in and told Paul he needed to get it in gear because the funeral service was at eleven.

Paul rode to church with Melissa, Jack, and their little girl, Clare. Paul sat in the back seat with Clare, who pressed herself into the corner as if she were a chick and Paul a snake. “Hi, there, sweetheart,” Paul said, but Clare just stared at him with those frightened eyes.

At the church Paul sat in the front pew with the rest of the family. Shelby came over, leaned down, and told Paul, Jack, and Buddy that they’d need to be pallbearers, and they nodded solemnly. Paul wondered who the other three would be.

The service started. “Doris Constance Martindell,” Shelby intoned—but then Paul’s mind began to wander. He thought about the church. He’d sat in those pews hundreds of times from his earliest memories until he left for college. Not just his brother and Aunt Doris but his parents had been very religious, too. His father would have his basketball players bow their heads and pray in the locker room before taking the court, then have them pray again after the game, never praying for victory but for the wisdom to use their talents as God willed. By the time Paul was on the team, their father was dead, and the new coach demanded no prayers. By Paul’s senior year, Shelby was on the squad, too, and he told Paul he was going to ask the coach to reinstate prayers before and after games. “Don’t be a jerk,” Paul had told him. Now, for the life of him he couldn’t remember if Shelby had brought it up with the coach or not. For sure, he couldn’t remember praying.

Rock of Ages Baptist Church—the name from the great old hymn.

Rock of ages, cleft for me,

Let me hide myself in thee.

What the hell did that mean, though? Well, no doubt everybody needed to hide at some point in his life. Lauren, when she fled Bill’s Ford, fled from him, did she think of herself as hiding? What would he find when he got back to Naperville? Would she have fled there, too?

Paul was surprised by a sob rising, rising from his innards, and he had to clench his teeth and swallow it, grimacing like a child swallowing a pill.

At that moment Shelby stepped out from behind the pulpit and like a master of ceremonies introducing the next act announced that “The Old Rugged Cross” had been Aunt Doris’s favorite hymn. But no singer stepped forward to perform, and Shelby didn’t invite the mourners to open their hymnals. Instead, he placed his hand over his heart and began to sing. When he got to, “I’ll cherish the old rugged cross, till my trophies at last I lay down,” his voice broke and he had a hard time continuing. Paul felt his eyes welling.

Finally the service was over. The relatives filed by the casket first, Paul just glancing at that absurd little wax doll lying there. Melissa, Trish, and the children turned up the side aisle and headed for the front doors while Paul, Buddy, and Jack sidled into the little room off to the side of the altar to await their duties as pallbearers.

Paul watched the mourners come up the center aisle to say their last goodbyes. One little old lady no larger than Aunt Doris hobbled up the aisle using a walker. When she got to the casket, she seemed to lose control of the walker and begin to fall. But then Paul realized she wasn’t falling. She was working herself down to her knees. She clasped her hands and closed her eyes and prayed.

“Who is that?” Paul whispered to Buddy.

“A friend of Aunt Doris’s,” Buddy said.

“I didn’t know she had any friends,” Paul said. Buddy just looked at him.

In fact, now that he thought of it, Paul was shocked at how many mourners there were. They just kept coming. How many will come to my funeral, he wondered. He’d have to leave money in his will to pay for professional mourners.

At the end of the line of mourners was Deb, and then Lauren.

When he saw Lauren, Paul tried to hold back, cursing himself, Stop it, you ridiculous old woman, but couldn’t keep his tears from coming for sure now, tears and hiccupping sobs.

Lauren must have heard him or saw him out of the corner of her eye because she turned and then came toward him, and he came out of the room to meet her.

“It’s OK, Paul,” she said gently. “She was the same as a mother to you.”

“I thought you were gone,” he said.

“What? Oh, earlier? Yes, Deb and I came to the church early to arrange the flowers. There wasn’t any professional florist or anything, just people here in the community bringing over flowers. Then we went back to the house, but we must have just missed you. When we got here, we decided it’d be better to sit in the back.”

Paul rubbed at his eyes like a little child.

Paul and his fellow pallbearers carried the casket to the open grave and sat it on the apparatus that, after the mourners had left, the cemetery workers would use to lower the casket into the ground. Then Paul, Buddy, and Jack sat down on the single row of folding chairs reserved for the family, the remaining mourners standing behind them. This time Lauren sat beside him.

Shelby made a few remarks. They prayed. Then it was over. The mourners filed past the family, offered condolences, and then began to drift off. The family rose from the chairs and talked about returning to the house where there was a ton of food brought by friends and neighbors. Paul remained sitting.

He was going to do something. He felt it coming. At first he thought he was going to begin to cry again, and he commanded himself, Don’t do it! Don’t you dare do it! But then he realized that wasn’t what he was going to do. He tried to rise from the chair but instead felt himself pitching forward. And then there he was, on his knees. He felt the others staring at him, no doubt shocked. They thought he was ill, probably, or had gone crazy. He wondered the same thing.

Then he felt a hand on his shoulder, and of course it was Lauren. She pulled him—gently, gently—pulled him up. He clung to her like he was afraid of the height.

The next day they’d make the long drive back to Naperville, and the day after that he’d be back at work. No doubt at lunch he’d go down to the bistro on the corner with the fellows from the law firm. He’d tell them about his three days out in the sticks, eating corn pone and greens, the outhouse back in the weeds the only toilet facilities. That would be good for a laugh. Depending on his mood, he might even tell them about falling on his knees, how for a moment there he believed in God. They’d no doubt laugh at that, too.

He would not, though, tell them that as she held him, he’d loved his wife again, and he felt certain that she loved him, but that he was afraid the love would fade as it had faded once before, and they’d go back to their old ways. If that happens, he told himself, I’ll fall on my knees again. He looked forward to falling.