An Everyday Illustration of Christian Supersessionism

According to Protestant theologian Karl Barth, the Old Testament constitutes “pre-time” that points forward toward God’s ultimate act of revelation in the person of Jesus Christ. In his words, the “covenant attested in the Old Testament is God’s revelation, because it is expectation of the revelation of Jesus Christ.” Accordingly, the Old Testament is construed as a time of “expectation” or pointing forward toward the incarnation, whereas the New Testament is construed as “recollection” or looking back and reflecting on the incarnation.[1]

Barth’s framework surfaces a pivotal issue for Christian biblical interpretation: we must articulate how the two testaments hang together. This territory is fraught with tensions and potential landmines. Too much emphasis on the Old Testament’s ability to stand on its own can lead to an excessively low Christology, whereas too much emphasis on its preparatory function leads us into the well-trod territory of Christian supersessionism. Also referred to as replacement theology, supersessionism posits in one way or another that the Christian community supersedes the role of God’s chosen and redeemed people. The election of the church is often pitted against Israel’s election, fashioning the people of Israel as merely an extended example of sin and unfaithfulness. This mode of biblical and theological thought has informed Christian theology beginning in the patristic era, continuing through the Middle Ages and Protestant Reformation, and carrying on into our own day.

Take, for example, Justin Martyr’s assertion that the Torah’s commandments of circumcision and Sabbath were instituted only because of Israel’s sinfulness and hardness of heart and are thus no longer relevant in the New Covenant. Or see Martin Luther’s description of the Jews as “a miserable, blind, and senseless people,” with the destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70 serving as “proof that the Jews, surely rejected by God, are no longer his people, and neither is he any longer their God.” It was Luther’s terrible portrayal of the Jews that Hitler used to buttress his own genocidal agenda.[2]

The events of the twentieth century—most notably the Holocaust and the subsequent founding of the modern state of Israel—should awaken us to this enduring dark streak running through the history of Christian thought. Contemporary theologians must wrestle with how we can hold on to the riches of Christian tradition while calling out and correcting its persistent anti-Judaism. The task of unmasking and rooting out Christian supersessionism may well be the central agenda for Christian theology in the coming decades. Even Karl Barth, whose theological framework and assertions in large part set the agenda for twentieth– and twenty-first–century theological conversation, reflects a deep ambivalence to the Jewish people, portraying Israel as reflecting all of the negative aspects of God’s election.

I am far from the first to make these claims. We have entered an intellectual environment in which dismantling supersessionism is increasingly central to the Christian theological task, and the frequency illusion may kick in: we begin to see supersessionism lurking behind every page of Christian theology and in every sermon we ever hear. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t there. In fact, unnamed supersessionist theology persists in perhaps the most insidious and overlooked of places: children’s Bibles. In this case, I will focus on one of the most popular illustrated children’s Bibles, the Jesus Storybook Bible (JSB), pointing out ways in which it upholds Barth’s Christocentric theological orientation and how, in doing so, it unwittingly promotes a supersessionist biblical hermeneutic.

Now that I have small children of my own, my husband and I are constantly on the lookout for theologically solid and beautifully illustrated children’s Bibles. The first time we read the JSB to our children from cover to cover, I found my Barthian self filled with deep ambivalence. The JSB regularly causes my eyes to well up at how beautifully the story of God’s never-ending, never-failing love is told. So on one hand, yes—“every story whispers his name.” The entire Bible from Genesis to Revelation attests to and points toward God’s incarnation in Christ. But at what cost is this assertion made?

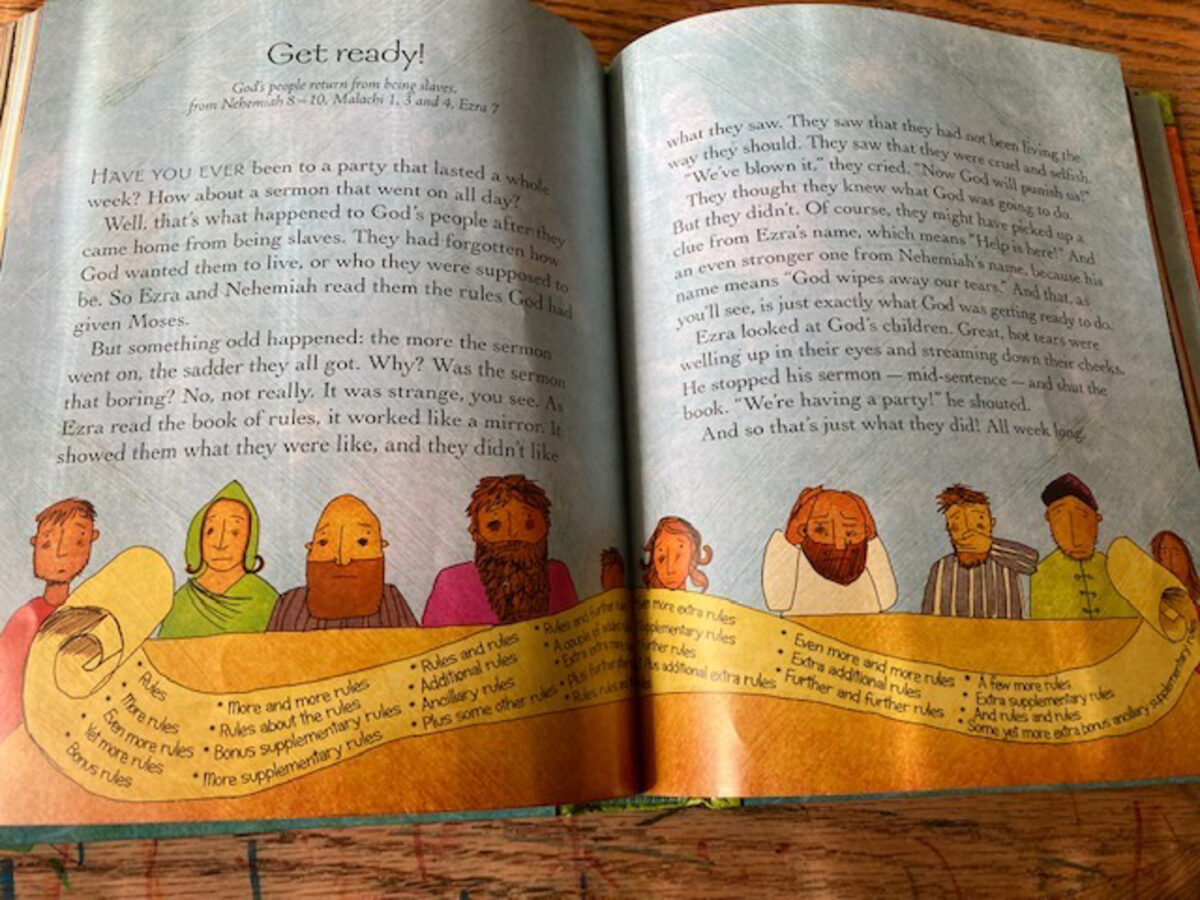

Despite that powerful core message, the JSB also drives a subtle but sure wedge between Judaism and Christianity, between what it calls “rules” and “grace.” Take, for example, the JSB’s treatment of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Malachi. In the illustration for this entry, the people are clearly distraught as they read a scroll detailing “rules, more rules, bonus supplementary rules, extra additional rules.”[3] Like the entirety of the JSB, this entry concludes by painting a beautiful portrait of God’s fathomless mercy and grace, but it arrives at that portrait by way of a negative caricature of Judaism. If we’re explaining the Torah and its centrality in God’s covenant with Israel to children, do we really want them walking away thinking it’s just a bunch of indiscriminate and endless rules? Is this how Torah is portrayed in passages like Psalm 119:35 (“Direct me in the path of your commands, for there I find delight”) and Psalm 119:72 (“the law from your mouth is more precious to me than thousands of pieces of silver and gold” [NIV])? It’s subtle, but the JSB’s entry on Ezra, Nehemiah, and Malachi replicates strong historical currents in Christian theology whereby Old Testament Judaism is seen as a futile system of works righteousness from which New Testament Christianity offers a certain freedom, a freedom from anthropocentric preoccupation with surface-level attempts at good behavior.

The JSB’s one entry on Paul further reinforces this common Christian juxtaposition. The entry begins: “Of all the people who kept the rules, Saul was the best.” He was one of the “Extra-Super-Holy People,” which is how the JSB describes the Pharisees. After his Damascus road encounter, the JSB records Paul’s preaching in this way: “‘It’s not about keeping rules!’ Paul told people. ‘You don’t have to be good at being good for God to love you. You just have to believe what Jesus has done and follow him. Because it’s not about trying, it’s about trusting. It’s not about rules, it’s about Grace: God’s free gift—that cost him everything.’”[4] On its surface, this language of grace and gift is apt, and yet it also perpetuates the trope of Judaism and Christianity as two mutually exclusive religious traditions. Paul thus serves as the prototypical convert who exposes the bankruptcy of Judaism’s focus on rules and spends his life touting the riches of its grace-based successor, Christianity.

As a member of a Messianic Jewish family, I find this kind of stark opposition between Judaism and Christianity to be deeply problematic. At the heart of my faith is the belief that Jesus (we call him by his Hebrew name, Yeshua) came as the long foretold and awaited Messiah of Israel. He came to fulfill God’s promises to Israel and to make a way for Gentiles (i.e., non-Jews) to enter into covenantal relationship with God. For our kids, instilling an abiding sense of Jewish identity provides the necessary context for cultivating in them a deep and substantive relationship with Jesus.

But this isn’t just a loss for my family. As I argue in my new book, Finding Messiah: A Journey into the Jewishness of the Gospel, the Christian church lost a key piece of its identity as it intentionally separated itself from God’s covenant with Israel. From the decoupling of Easter from Passover to the political finality of Christian worship on Sunday, Christian history is a trail of discarded ties to Judaism and the Torah, and that trail is a rejection of God’s gifts. And it is to our detriment that the JSB continues on this path.

Indeed, in my estimation, the JSB’s posture regarding Judaism versus Christianity is tightly connected to another curious feature of its core message. A strong repeated theme throughout the JSB is that God loves us, no matter what. This is, of course, true. But what is notably underemphasized is our commission as Jesus’s disciples and the way in which we are called to continue the work that Jesus began. Could the stark contrast between Judaism and Christianity perpetuated throughout the JSB inform its relative silence on Christian discipleship?

Living in obedience is a clear focus in Jewish tradition—for the Jewish people, this is what the “rules” are all about. Indeed, the rules teach us what it means to live as God’s people, to respond to the incredible grace given in God’s act of election. Israel has always understood that the covenant is two-sided; indeed, the 613 mitzvoth (commandments) that stand at the heart of Jewish life spell out Israel’s covenantal responsibilities in light of its status as God’s chosen people. This is where too blunt a contrast between grace through faith (the slogan of Protestant Christianity) and works righteousness (the ubiquitous and incorrect Christian portrayal of Judaism) causes problems. In portraying Israel’s life as striving to keep a list of arbitrary rules, the baby gets thrown out with the bathwater, and humanity’s role in the divine-human covenant gets obscured.

In the end, I absolutely want my kids to understand the inexpressible vastness of God’s love, forgiveness, sovereignty, and grace. But I also want them to understand the importance of dedicating their lives to serving the inbreaking of God’s kingdom, here and now. Mustn’t our embrace of God’s love lead us to live our lives as a response to that love, such that we shape our lives around it? Isn’t the story incomplete if it doesn’t include our response to grace and election? In this regard, Christianity has much to learn from God’s enduring covenant with the people of Israel.

[1] Barth, Church Dogmatics, vol. 1.1, The Doctrine of the Word of God, trans. G. T. Thomson and Harold Knight (New York, NY: T&T Clark, 2004), 81; emphasis added.

[2] See Dialogue with Trypho, esp. chs. 10–12in The Fathers of the Church, vol. 6, Writings of Saint Justin Martyr, trans. Thomas B. Falls (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1948); and Luther, “On the Jews and Their Lies,” in The Essential Luther, ed. and trans. Tryntje Helfferich (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 2018), 284–303. For more on Luther’s antisemitism and its influence on Nazi Germany, see Christopher J. Probst, Demonizing the Jews: Luther and the Protestant Church in Nazi Germany (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012) and Richard S. Harvey, Luther and the Jews: Putting Right the Lies (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2017).

[3] Sally Lloyd-Jones, The Jesus Storybook Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Zonderkidz, 2007), 170–71.

[4] Lloyd-Jones, The Jesus Storybook Bible, 340.