The white walls and thatched roof of Shakespeare’s Globe overlook the Thames in London’s Bankside district. Since its opening in 1997, productions staged in this reconstruction of the outdoor theater owned by William Shakespeare’s playing company have adhered to what scholars call “original practice” principles: they loosely approximate the conditions that governed performances in the original Globe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[1] This mild antiquarianism is part of the theater’s appeal; advertisements along the embankment encourage passing tourists to join the groundlings and, like their early modern counterparts, mill around the open area at the foot of the stage as they catch lines delivered without the aid of microphones.

Actors, directors, and reviewers alike have particularly highlighted the effect of the original performance principle of shared light on audiences at the reconstructed Globe. To acknowledge the fact that sixteenth- and seventeenth-century drama was performed during daylight hours, everyone in the Globe’s playing space—actors as well as audience members—is evenly lit by inconspicuous lighting fixtures. Visibility brings audiences and their reactions into the larger circuit of meaning created within the theater, and critics such as Pauline Kiernan have discussed the distinct psychological effect of this visibility on the Globe’s audience members: it encourages them to offer both verbal and nonverbal feedback as action unfolds onstage. Actors often point to shared light and the resultant engagement of audiences as one of the primary draws of playing at the Globe; the actor, playwright, and director Mark Rylance describes the atmosphere there as “highly charged,” noting that the audiences at the Globe “weren’t to be ignored. . . . It was as if the audience had been gagged, and were now able to do and say what they liked.”[2]

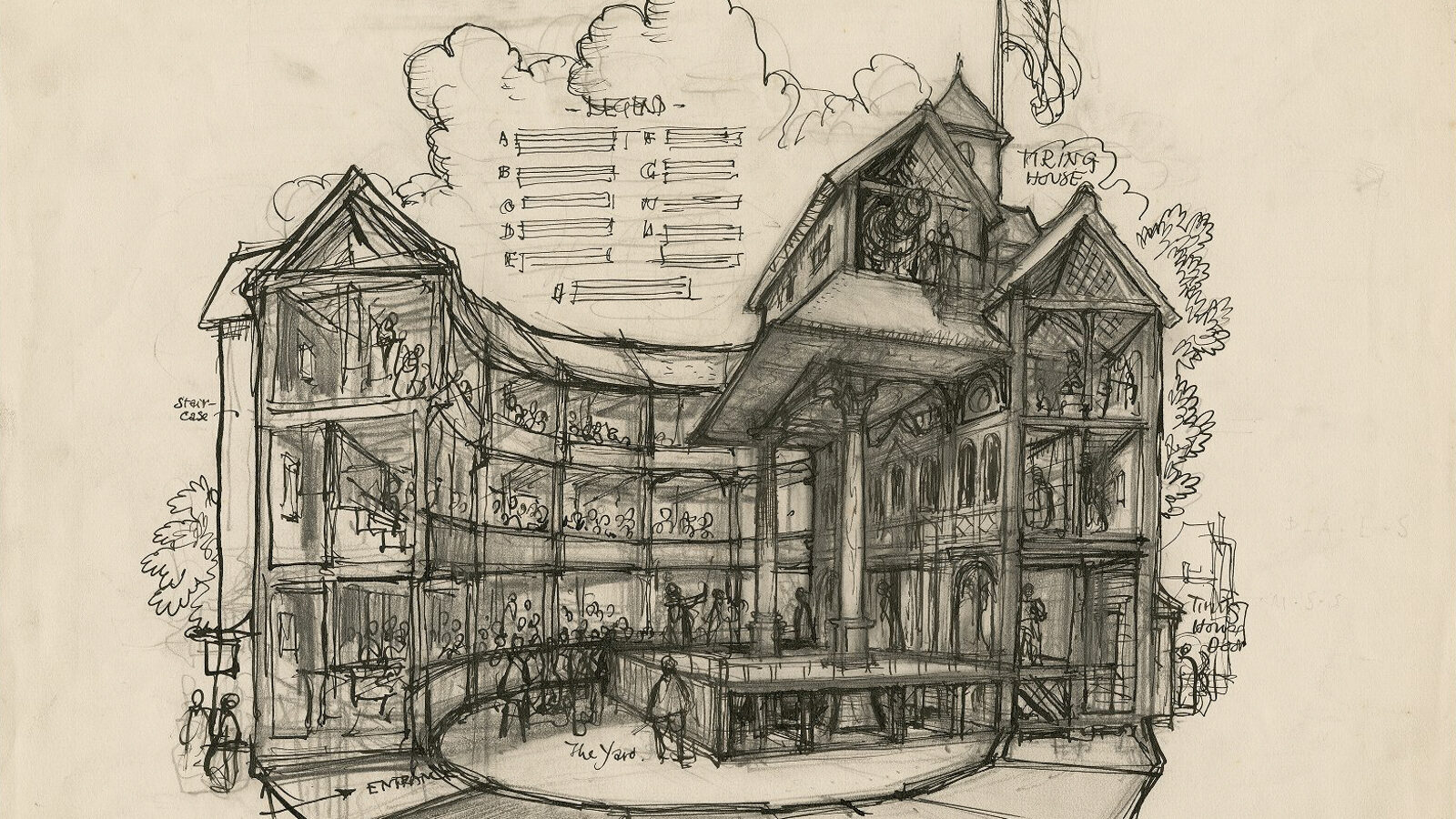

Cyril Walter Hodges, Elizabethan Theater Sketch, 1909–2004. Courtesy of Folger Shakespeare Library.

Shakespeare’s comedies tend to play well in shared light. Although the contents of the playwright’s jokes are often inscrutable to modern audiences, especially those unfamiliar with the plays, the rhythms of verbal sparring and physical comedy translate well across the centuries. As a result, comic performances are generally able to signal not only when they want their audiences to laugh but also why and in what way. Lucy Baily’s recent staging of Much Ado About Nothing at the Globe, for instance, established an energetic rapport with its audience predicated upon on each party’s ability to see and respond to the other, with the actors improvising based on the laughter of the audience.

The playing conditions at the Globe take on a different aspect in the context of Shakespeare’s tragedies, however. Shared light still elicits participation from audience members, but just what form this participation ought to take is far less clear, since tragic drama hinges upon the display of unjust suffering. What response is fitting upon witnessing the death of Cleopatra, the manipulation of Othello by Iago, or the betrayal of Timon by his friends? That these remain live questions today, over two decades after the Globe’s reconstruction, testifies both to the contingency of each tragic production and the perversity of staging tragic suffering under shared light. In such conditions, tragedy becomes an incitement to respond where no response seems to fit.

Helena Kau-Howson’s summer 2022 productionof King Lear at the Globe was, as other reviewers have noted, scattered and stodgy.[3] Kathryn Hunter gave a commanding performance as Lear, but the ensemble as a whole fell short of the dynamism that carries audiences through the best renditions of the play. In spite of this, Kau-Howson’s Lear has remained with me, given that it contained a sequence of events unlike any I have witnessed in a theater. First, incongruous laughter erupted during the famous cliff scene of act 4, scene 5.[4] The Duke of Gloucester’s slow march toward self-destruction elicited chuckles from spectators who were more inclined to revel in the pleasure of dramatic irony—the discrepancy between their knowledge and his—than attend to the suffering from which this irony derived. In the context of a play that probes the limits of physical and mental fortitude when placed under duress, laughter disclosed a relational gulf between character and audience, between Gloucester’s grief as it stumbled toward culmination and those who looked on.

In answer, the actor playing the role of Gloucester took it upon himself to chastise the audience for their callous laughter. Rather than ignore the groundlings, he brought the performance to a halt by kneeling silently and with outstretched arms at the front of the stage. The effect of this relatively brief performance decision was remarkable; as when Plutarch’s Coriolanus exhibits his battle scars to a capricious Roman public, this improvisation drew unmistakable attention to the evidence of Gloucester’s suffering and forced the audience at the Globe to confront the absurdity of their response to his condition. The silence that followed spoke to a newfound recognition on the part of the those watching of their connection to and implication in what occurred onstage.

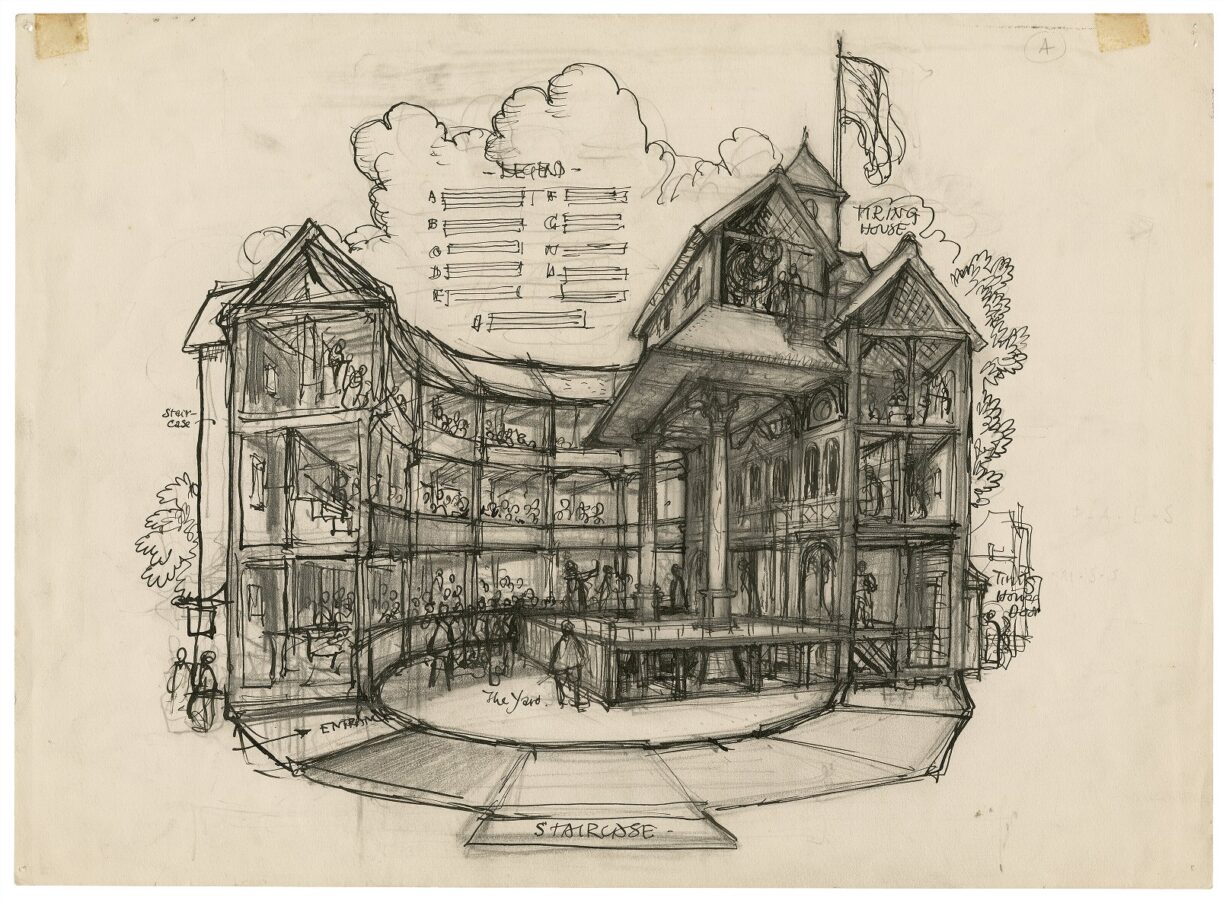

Cyril Walter Hodges, Cutaway View Sketch of the Globe Playhouse, 1909–2004. Courtesy of Folger Shakespeare Library.

Taken together, the laughter of the audience and the improvisation of the actors in Kau-Howson’s Lear highlighted the unique potential of Shakespearean tragedy when staged in shared light. The sensory ecology at the Globe encourages audiences to respond to suffering as it occurs onstage. At the same time, it also enables performers to account for and even correct these responses within the fictive world of the play. This back-and-forth—a dialogue of sorts—acts as a mechanism for the moral formation of the audience. In offering both freedom and censure, tragedy in shared light amplifies the call placed upon us by the suffering of others, and it provokes us to answer this call with actions that reflect our shared humanity. Ultimately, Kau-Howson’s Lear left audience members better prepared to respond to suffering in their lives outside of the theater.

THE DARKENED THEATER

The active dialogue between audience and performance that characterized Kau-Howson’s Lear differs markedly from traditional accounts of how staged tragedy moves its audience to moral action. In his Poetics, Aristotle claims that the work of tragedy turns upon the persuasive power of suffering; catharsisoccurswhen a performance employs tragic elements—plot, character, thought, diction, and spectacle—so that the performance moves the audience to pity the suffering of a tragic hero and fear the possibility of this same suffering being meted out to them. For Aristotle, the performance works as an active force upon the emotions of spectators, clearing, as Martha Nussbaum notes, the emotions of impediments. This clearing away, sometimes understood as a kind of purgation, teaches spectators to act virtuously in other parts of their daily lives.[5] Within the space of the theater itself, Aristotelean tragedy asks only that its audience submit to the work of tragic mimesis on the emotions.

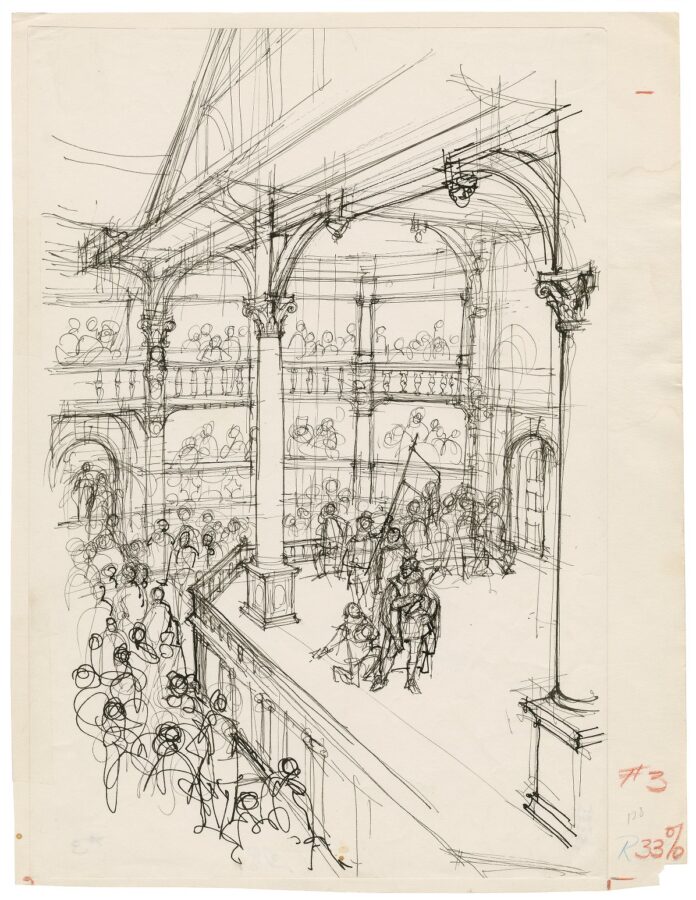

Cyril Walter Hodges,

Illustration for Promotion Brochure of the Interior of the Proposed Reconstructed Globe, for the “Shakespeare’s Globe in America” Project in Detroit, 1909–2004. Courtesy of Folger Shakespeare Library.

More recent theories have found in the passivity implied by Aristotle the very mechanism by which tragedy constitutes virtue. Stanley Cavell, for instance, understands the physical space of the modern theater—darkened seating areas, neatly divisive arm rests, proscenium arches, and controlled spotlighting—as essential to tragedy’s ability to encourage audiences to act in accordance with the good. Fashioned into silent voyeurs, we witness tragic suffering while simultaneously being made to feel our own inability to intervene on behalf of those who suffer. For Cavell, this manufactured helplessness performs a clarifying function, calling to mind the various ways in which we ought to intervene on behalf of those suffering outside of the theater. Cavell writes, “In another word, what is revealed is my separateness from what is happening to them; that I am I, and here. It is only in this perception of them as separate from me that I make them present. That I make them other, and face them.” Paradoxically, the constraints placed on us by modern theaters reveal our freedom to act in response to tragedy, forcing a single inexorable question: “Why do I do nothing, faced with tragic events?”[6]

Cavell’s account of tragedy’s morally formative qualities rings true. Tragedy in general, and Shakespearean tragedy in particular, stages suffering at least in part as a way of alerting us to the claim made upon our actions by the suffering of others—the ache and thrill of attending to the story of characters like Lear and Lavinia lies in the realization that we do not exist in separation from their suffering; we exist in essential relation to it. Understood this way, tragic theater uses the tools of representation—especially the staging of characters who do not exist outside of the theater—to remind us of the shared humanity that underlies our experience of the other. By tying this work of tragedy to the physical space of the modern theater, however, Cavell limits the form’s scope. There are and have always been other modalities for engaging with staged mimesis, and these modalities offer other frameworks for thinking about how tragedy asks us to consider our connection to others and reform our behavior as a result. To Cavell’s account of tragedy in the darkened theater, then, we might add the question of tragedy’s relationship to virtue in shared light.

SHARED LIGHT

In contrast to the restraints imposed upon audiences in modern theatrical contexts, shared light theaters grant spectators the freedom to react to a performance in real time. The laughs, gasps, claps, and murmurs of spectators form the soundtrack to performances at the Globe, registering a play’s events on a minute-by-minute basis. The sensorium cultivated by shared light gives rise to a remarkable form of honesty; rather than assessing the play as a totalized whole, audiences are encouraged to offer gut responses made in the heat of the moment. The overall effect is to make the theatrical experience similar to that of viewing a sporting event, where boos, cheers, and claps record a crowd’s understanding of each act’s significance as it happens. Indeed, actor David Fielder describes his performances at the Globe as akin to acting at “a football match.”[7]

The freedom granted by shared light to audiences has other implications as well. Stripped of the limits on meaning that characterize Cavell’s modern theater, performances in shared light theaters risk provoking responses that are unfitting or even distasteful. For instance, Pauline Kiernan recalls the “jingoistic, insensitive” chants that broke out at one early performance of Henry V at the Globe. As Rylance, playing Henry, solemnly read out the names of the French soldiers killed at the battle of Agincourt, “a small group of playgoers in the yard cheered.” While extreme, such behavior is nevertheless endemic to the freedom afforded by shared light to spectators. It was Rylance himself, after all, who described the fact that audiences can “do and say what they liked” as the chief pleasure of playing at the Globe.[8] It should come as no surprise that audiences sometimes exercise their license in uncomfortable ways.

The case of Rylance’s Henry V also demonstrates that the freedoms afforded by shared light extend to performers as well as to the audience. Rylance recognized the xenophobia at play when his audience applauded the death of the French soldiers. In answer to their cheers, Rylance turned his back on the audience and completed the scene out of their hearing, effectively punishing them for displaying the kind of vulgar nationalism that the play attempts to interrogate.[9] The corrective power deployed by Rylance in this moment would not be possible within the context of Cavell’s modern theater; yet this impossibility points to an alternative means through which performances staged in theaters such as the Globe can encourage audiences to more virtuous action. By allowing for interaction between spectators and actors, shared light opens a space for moral dialogue. In the case of tragedy, with its portrayal of unjust suffering, this dialogue often turns upon the question of what constitutes a fitting response to the pain experienced by others.

GLOUCESTER IN SHARED LIGHT

This brings us to the moment in Kau-Howson’s Lear that exemplified the morally formative potential of tragedy staged under shared light. Act 4, scene 5 opens on a pair of figures stumbling toward the cliffs of Dover: Edgar, the eldest son of the Duke of Gloucester, and Gloucester himself. The scene’s notable place within the Shakespearean canon comes in part from its dramatic irony; having been recently blinded, Gloucester unknowingly tasks his son with facilitating his suicide attempt.

GLOUCESTER

When shall I come to th’ top of that same hill?

EDGAR

You do climb up it now. Look how we labor.

GLOUCESTER

Methinks the ground is even.

EDGAR

Horrible steep.

Hark, do you hear the sea?

GLOUCESTER

No, truly.

EDGAR

Why, then your other senses grow imperfect

By your eyes’ anguish.[10]

Edgar guesses his father’s intentions. He manages to trick the old man into believing they have arrived at the cliff’s summit, all the while giving asides that assure the audience that the pair still occupy flat ground. Edgar’s vivid yet wholly false description of an imminent, towering precipice overcomes his father’s doubts:

EDGAR

Come on, sir,

Here’s the place. Stand still. How fearful

And dizzy ’tis to cast one’s eyes so low!

The crows and choughs that wing the midway air

Show scarce so gross as beetles

. . . .

I’ll look no more,

Lest my brain turn and the deficient sight

Topple down headlong.

GLOUCESTER

Set me where you stand.[11]

Letting go of Edgar’s arm and positioning himself at what he believes to be cliff’s edge, the old man summons the will to perform his final act.

GLOUCESTER

O you mighty gods!

[He kneels.]

This world I do renounce, and in your sights

Shake patiently my great affliction off.

If I could bear it longer and not fall

To quarrel with your great opposeless wills,

My snuff and loathèd part of nature should

Burn itself out. If Edgar live, oh, bless him![12]

Even a cursory reading of the play leading up to this moment cannot help but register Gloucester’s inner turmoil and the filial love that motivates Edgar’s deception. After all, Gloucester signals his intention to throw himself off the cliff earlier in act 4; he asks Edgar “dost thou know Dover?” before noting that “from that place / I shall no leading need.”[13] What is more, the many troubles that drive Gloucester toward suicide take place within the scope of the play: his misjudgment of Edmund and Edgar, his loyalty to a king who has fallen from grace, and the vicious torture he experienced at the hands of Cornwall and Regan all play out in full view of the audience. By making Gloucester’s affliction apparent throughout the play’s first acts, Shakespeare prepares us for the poignancy of act 4, scene 5. The actors in Kau-Howson’s performance, Kwaku Mills (who played Edgar) and Diego Matamoros (who played Gloucester), mined the scene for its pathos; they followed 1983 and 2018 film productions in punctuating their exchanges with choked sobs.

And that is why it was so shocking to hear the audience at the Globe break out in laughter at Gloucester’s gullibility. Furtive chuckles began almost as soon as the nature of Edgar’s deception became clear, and these only increased in volume and merriment as the scene progressed. Edgar’s initial assurances to Gloucester that they climbed a “horrible steep” hill were greeted by chortles that, by the time the pair arrived “within a foot of th’ extreme verge,” had become robust laughter.[14]

The laughter of the audience surprised and jarred the actors, Mills especially. Lines that were clearly intended to illustrate Edgar’s desperation at his father’s despair were greeted by cackles from those nearest to him. Having seized upon the simple fact of the trick being played on Gloucester, spectators seemed uninterested in attending either to the disability that formed the basis of the old man’s gullibility or to the stakes involved in Edgar’s guidance. Laughter in this case revealed a spectacular and multivalent failure: the failure of a performance to prepare its audience to interpret a particular scene in a fitting manner but also the larger and more troubling failure of the audience to recognize the depth of Gloucester’s suffering. To the rest of us who watched, it felt as if the gulf between the performers’ expectations and the audience’s reaction might bring the edifice of the play crashing down around the ears of Edgar and Gloucester.

Matamoros’s Gloucester took charge of the performance at this disjunction. Surrounded on three sides by laughing groundlings, and with his eyes covered by a bloody cloth, the actor fell to his knees as the text dictates. Before delivering Gloucester’s renunciation of the world and its “great affliction,” however, Matamoros maintained his kneeling position, wordlessly holding his arms wide for an uncomfortable length of time—5 seconds, 10 seconds, 15 seconds, 20 seconds. As he did so, he turned his head left and right as if to scan an audience that he could not see. Only after pausing silently in this way did Matamoros deliver the remainder of his character’s passage and, after, fall forward onto his face.

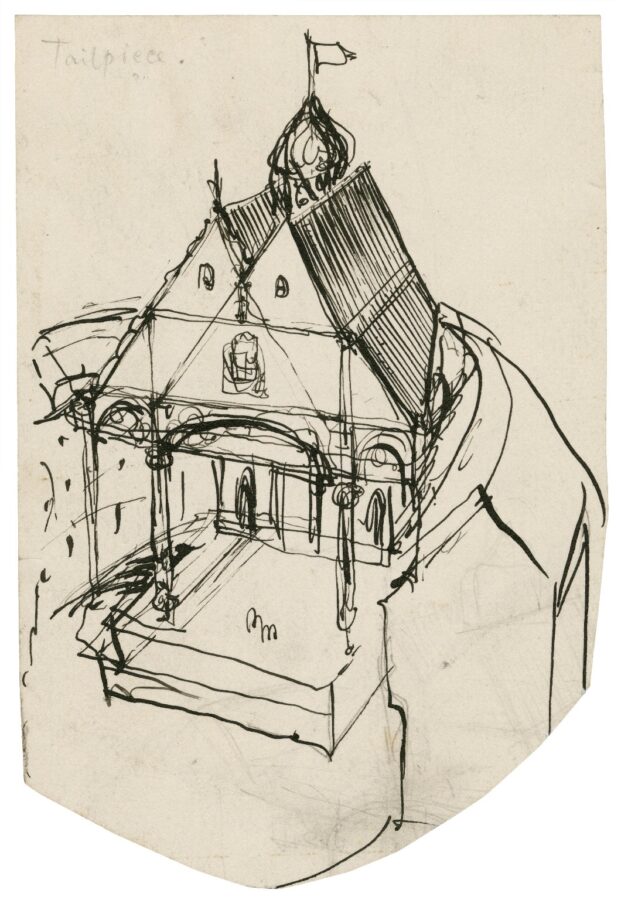

Cyril Walter Hodges, Exterior Sketch of the Second Globe, 1909–2004. Courtesy of Folger Shakespeare Library.

This moment of improvisation was at once authoritative, eerie, and condemnatory. The combination of outstretched arms and slowly rotating head had the effect of drawing the whole theater’s attention to Gloucester’s disabled body, reminding everyone of the violence that had been visited upon that body just a short time before. His silence too was meaningful, as it performed the response he felt most appropriate to his character’s plight. In sum, Matamoros brought the audience face-to-face with the stakes of Gloucester’s procession toward the cliffs: this, his silence seemed to say, was the last desperate act of a character marked by the play as “more sinned against than sinning.”[15] The shift from laughter to silence that resulted from his actions indexed the power of his improvisation.

The decision to respond to, rather than ignore, the laughter of the Globe’s audience fulfilled the function assigned to tragedy by both Aristotle and Cavell: to provoke audiences to virtuous action. Spectators exercised their freedom to respond to the performance on their own terms by poking fun at Gloucester’s suffering, and in doing so, they revealed their own disconnection from the suffering taking place before them. Under such conditions, Matamoros’s improvisational display of Gloucester’s body and his accusatory, sightless gaze became a rebuke to those who laughed and a means of bridging the gap between audience and character. It clarified the absurdity of laugher as a reaction to tragedy and, through silence, modeled a more humane response. Cavell describes tragic drama as an art form uniquely positioned to reveal our separateness from the suffering of others—the fact that we “cannot do and suffer what is another’s to do and suffer”—while also calling to mind how we ought to respond to this separateness in our own lives.[16] Matamoros’s improvisation performed this function for the audience at the Globe.

And yet, Kau-Howson’s Lear accomplished this moral work of tragedy by means of playing conditions that drastically differ from those described by Cavell. It was the active dialogue opened by shared light between audience and performance, rather than the constrained helplessness of the darked theater, that encouraged spectators to consider the weight of their actions in response to Gloucester’s pain. The freedom of the audience to express their responses and the freedom of the performance to incorporate these responses into the staging of the play itself together enabled the audience of Kau-Howson’s Lear to experience in and through their bodies the claims made on us all by suffering. None of this could have taken place without shared light.

It is fitting, then, that the audience saw the reformation of their responses to suffering reflected back to them in the following moments. After all, the cliff scene ends not in Gloucester’s suicide but with a Gloucester newly convinced of his life’s sanctity.

EDGAR

Therefore, thou happy father,

Think that the clearest gods, who make them honors

Of men’s impossibilities, have preserved thee.

GLOUCESTER

I do remember now. Henceforth I’ll bear

Affliction till it do cry out itself,

“Enough, enough” and die.[17]

Believing his life to have been preserved through divine intervention, Gloucester finds strength to carry on in the face of affliction. And though he does perish eventually, it is as his heart, “twixt two extremes of passion, joy and grief, / burst smilingly” upon being reunited with Edgar.[18]

Having been brought through laughter and into silence by Kau-Howson’s Lear, the audience too took part in Gloucester’s redemption. In their case, it was a redemption borne of the knowledge that their worst impulses have been acknowledged and corrected within the fictive space of the theater. I’d like to think that others who saw this summer’s production of Kau-Hudson’s Lear left the Globe as I did, with a visceral reminder of what we owe to those around us, especially when we encounter one another in the midst of tragedy.

[1] For a discussion of these conditions, see Andrew Gurr, Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1987); and Erika T. Lin, Shakespeare and the Materiality of Performance (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

[2] Kiernan, Staging Shakespeare at the New Globe (New York, NY: St. Martin’s, 1999), 18; and Rylance quoted in Kiernan, Staging Shakespeare, 20.

[3] See, for instance, Andrzej Lukowski, “King Lear Review,” Timeout, June 18, 2022, https://www.timeout.com/london/theatre/king-lear-review-1; and Sonny Waheed, “King Lear: Making the Complicated, Confounding” Theatre Vibe, June 20, 2022, https://theatrevibe.co.uk/2022/06/20/review-king-lear-shakespeares-globe-2022/.

[4] The cliff scene appears as act 4, scene 5 in the Folio version of the play but as act 4, scene 6 in the two quarto versions printed in 1608 and 1619. Quotations in this essay follow the Folio version, so the act, scene, and line numbers of that version are adopted as well. Although the relative authority of the quartos and Folio remains a topic of heated conversation among textual critics, the cliff scene differs little across these different versions.

[5] See Aristotle, Poetics, trans. Stephen Halliwell, W. Hamilton Fyfe, Doreen C. Innes, and W. Rhys Roberts, rev. by Donald A. Russell, Loeb Classical Library 199 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 1449b22–28, and 1450b1–20; Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy, updated ed. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 390; and Richard Janko, “From Catharsis to the Aristotelian Mean,” in Essays on Aristotle’s Poetics, ed. Amélie Oksenberg Rorty (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 341. [SEE diacritical in Amelie above]

[6] Cavell, “The Avoidance of Love: A Reading of King Lear,” in Must We Mean What We Say?,updated ed. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 311–12 and 312.

[7] Fielder quoted in Kiernan, Staging Shakespeare, 134.

[8] Kiernan, Staging Shakespeare, 20; and Rylance also quoted in Kiernan, Staging Shakespeare, 20.

[9] Rylance quoted in Kiernan, Staging Shakespeare, 20.

[10] Shakespeare, The Tragedy of King Lear, in The Norton Shakespeare, 3rd ed., ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Walter Cohen, Suzanne Gossett, Jean E. Howard, Katharine Eisaman Maus, and Gordon McMullan (New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 2016), 4.5.1–6. References are to act, scene, and line.

[11] Shakespeare, King Lear, 4.5.15–19 and 4.5.27–30.

[12] Shakespeare, King Lear, 4.5.36–42.

[13] Shakespeare, King Lear, 4.1.69 and 4.1.75–6.

[14] Shakespeare, King Lear, 4.5.27.

[15] Shakespeare, King Lear, 3.2.60.

[16] Cavell, “The Avoidance of Love,” 312.

[17] Shakespeare, King Lear, 4.5.74–9.

[18] Shakespeare, King Lear, 5.1.190–1.