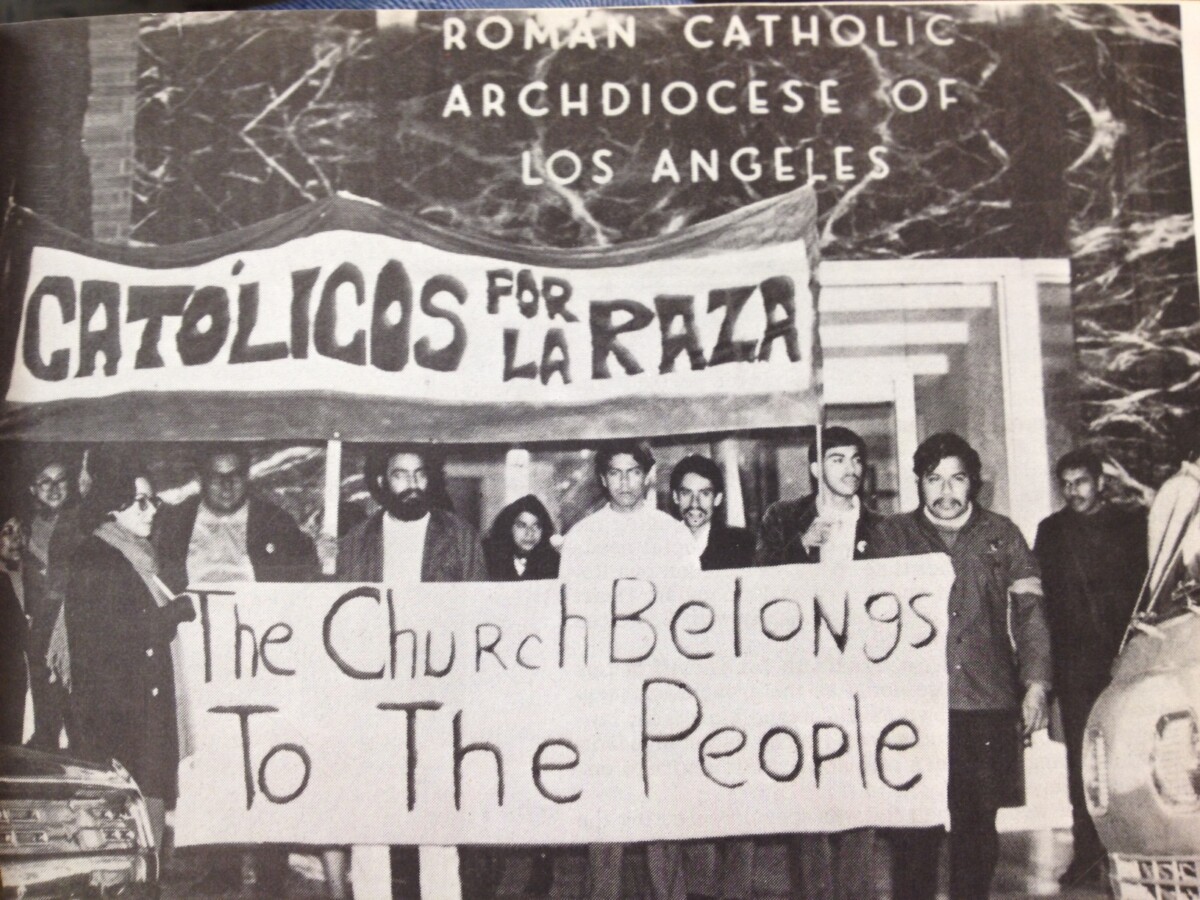

On Christmas Eve 1969, a melee broke out at St. Basil’s Roman Catholic Church in Los Angeles. The disruption to James Francis Cardinal McIntyre’s midnight Mass was a protest by Católicos Por La Raza, a group of Chicano organizers who intended to challenge their second-class status within a largely Anglo and racist Catholic Church.1 This essay will explore the theological implications of Católicos’ protest. What does it mean for believers on the fringes of faith to confront their leaders during Mass, a moment in the Catholic tradition called the “source and summit of Christian life?” Is it ever appropriate for believers to disrupt the sacrament that functions as the “efficacious sign and sublime cause of that communion in the divine life and that unity of the People of God by which the Church is kept in being?”2 Finally, where can God’s work be found in all of this?

Católicos formed in the fall of 1969 as an association of Chicano Catholic student activists who were proud of both their Catholic and Chicano heritage, twin identities that allowed them to see the suffering that racism in the Catholic Church had caused their community. Many members of the group began their work in the Chicano rights movement alongside Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers of America (UFW). Chavez’s leadership of the UFW made clear how the power held by religious institutions could be harnessed by activists to further their causes and benefit their communities. Católicos, formed with the encouragement of Cesar Chavez in 1969, brought together students from the Chicano Law Students Association at Loyola Marymount College, the La Raza newspaper, and the United Mexican American Students of Los Angeles City College.3 Many of the founders had grown up in Catholic parochial schools and knew well how Catholic social teaching was patterned after the life of Jesus Christ. The late 1960s was a time of upheaval in the Catholic Church as bishops, theologians, and lay believers came to grips with the changes of Vatican II, such as the call for wider participation of lay Catholics and greater attunement to the plight of the poor. Within the American political scene, Católicos leadership took their cues from other activist and civil rights organizations. Many had ties to La Raza Unida Party, a Chicano political party, and the 1968 school blow-outs, a series of walk-outs staged by Chicano student activists to protest educational inequalities.4

In Católicos’ eyes, the Catholic Church was an Anglo social institution that oppressed Chicanos by denying them equal opportunities and justice within ecclesial structures.5 Instead of contributing to Chicano well-being, the Catholic Church took financial, social, and religious advantage of Chicanos who relied on it for their sacramental and spiritual needs. Católicos claimed that the Catholic Church, “the strongest and richest institution in the world,” had been stolen from the poor, including Chicanos, who in their vulnerable state “ha[d] to dance, beg, plead, and steal for better housing, education, legal defense and other Chicano goals.”6

In Los Angeles, Chicano grievances against the diocese were especially clear. In 1969, the archdiocese shuttered Our Lady Queen of Angels, a parochial school that had served a predominantly Chicano community, in the very same year that it opened a new $4 million church complex at St. Basil’s, which was located in what Mario García calls the “trendy Wilshire district.”7 While many Chicanos could hardly pay their rent, the diocese owned properties and assets worth over $1 billion, according to Católicos founder Ricardo Cruz, and these properties included tenements that were rented to poor Mexican Americans. The Los Angeles diocese, one Católicos leader accused, was a slumlord over its most faithful parishioners.8

Católicos believed these injustices were tied to longstanding systematic inequalities in Catholic leadership. Across the southwest, Chicanos made up 67 percent of Catholics, yet in Los Angeles only 5 percent of the priests had Spanish surnames.9 There, Cardinal McIntyre was an Irish bishop whose priests often had to intervene when he used racist slurs. McIntyre ran his diocese, in the words of Jesuit historian Patrick McNamara, as an “authoritarian regime,” and he considered social action, according to Católicos leadership, “in the same vein as hell.”10 On a national level, there was not a single native Spanish-speaking bishop in the US Catholic Church even though at that time the Catholic Church was composed of nearly 23 percent Spanish speakers.11 Ministries to Spanish-speaking Catholics were few and far between.

The leaders of Católicos believed that the example set by their local church stood in stark contrast to the mission of Jesus Christ, who in his lifetime identified with marginalized peoples. The founder of Christianity extolled the poor as privileged members of God’s kingdom, but the Diocese of Los Angeles neglected the poor and ignored their suffering. Christ’s original followers were commoners brought together by their Lord’s vision for a radically egalitarian social order, but the Catholic Church had grown elitist, wealthy, and insulated from the concerns of the poor.12 Católicos believed that Jesus Christ, unlike their local leadership, was a radical manifestation of God’s love who led a social revolution against the hierarchies of the Roman Empire and the religious establishments of the Jewish tradition. Christ, with the church he founded, identified with the poor by forsaking worldly power and seeking the relief of the most excluded members of society.13

Following their understanding of Christ, Los Angeles Católicos believed that Christians had a calling to ensure the church’s well-being in fidelity to the legacy of its founder. Católicos thus made direct political demands as they called for believers to follow the example of Jesus Christ. Cruz wrote,

As Mexican-Americans, as Católicos, as Chicanos, that as members of the Catholic Church, it is our fault if the Catholic Church is no longer a church of blood, a church of struggle, a church of sacrifice. It is our fault because we have not raised our voices as Catholics and as poor people for the love of Christ. We can’t love our people without demanding better housing, education, health, and so many other needs we share in common. . . . We must return the church to the poor. Or did Christ die in vain?14

Cruz’s conviction was in line with other liberation theologians. Juan Luis Segundo described how “the signs of the times and the soteriological dynamic of the Christian faith historicized in new human beings insistently demand the prophetic negation of a church as the old heaven of a civilization of wealth and empire and the utopian affirmation of a church as the new heaven of a civilization of poverty.”15 For Cruz and Segundo, the prophetic denunciation of the Catholic Church’s wealth and indifference to the poor was a necessity demanded by authentic Christian faith.

As Católicos began to organize in the fall of 1969, Cardinal McIntyre refused time and time again to meet with them to consider their grievances. In response, Católicos decided to take a prophetic course of action by interrupting the cardinal’s Christmas Eve Mass. According to García, Católicos “insisted that the only way to get awareness in the community about the failures of the Church was to get publicity and the only way to get publicity was through confrontation.”16 Católicos chose the newly constructed St. Basil’s as the site of their protest because it represented to them the Catholic Church’s hypocrisy and injustice toward the Chicano community. Católicos planned to hold an alternative Christmas Eve Mass outside of St. Basil’s that would conclude shortly before the cardinal’s own service ended. Then, a group of Católicos would bring candles into the sanctuary of St. Basil’s and march down the center aisle to the front, where they would face the congregation and present a list of their demands to the cardinal and congregation.

Some members of Católicos were suspicious of this course of action.17 Would an interruption of the Mass disrespect Christ, whom Catholics believe is truly present in the consecrated bread and wine? Interrupting the Eucharist to protest injustice could run counter to longstanding Catholic teaching that recognizes sacramental validity even in the context of ecclesial sin. This teaching holds that Jesus Christ is present in the elements of bread and wine even if those who consecrated that bread and wine were clearly sinful. God’s grace in the Eucharist is efficacious because of the forms and words proper to the Mass, not because of the righteousness of its officiants. Would interrupting the Mass interrupt God’s gift of grace to the church, which overwhelms human frailties and makes God truly present?

Católicos decided that allowing the continued injustice would be a greater sin than confronting the hierarchy head on. In a message announcing the Christmas Eve protest, Cruz asserted that silence in the face of injustice constitutes an endorsement of structural sin. Local churches, he said, “stand as silent symbols in a time when silence means continued war, hunger, and poverty.”18

Católicos’ decision to interrupt the Mass can be understood through the work of Tissa Balasuriya, a liberation theologian from Sri Lanka, who has argued that the toleration of social sin at Mass is part of a long-standing historical “social conditioning of the Eucharist.” Dominant social forces, Balasuriya contends, have subjected and silenced the prophetic force of Christian faith that Christ established in the earliest eucharistic communities. Although these communities were characterized by radical equality, sharing, compassion, and communion, today “feudalism, capitalism, colonialism, racism, and sexism have all tended to make the Eucharist conform to their priorities.”19

Furthermore, as Balasuriya argues, the Eucharist has become a tool used by the religious and political elites to maintain the status quo through the continued subordination of marginalized believers in the faith community. By claiming that all are welcome to share in Holy Communion regardless of socioeconomic status, a high sacramental doctrine of the Eucharist bowdlerizes the material and social divisions that ought to scandalize believers into action on behalf of their suffering brothers and sisters.20 A eucharistic theology that focuses on spiritual unity and sacramental efficacy while neglecting the material realities of injustice in the body of faith dresses up the sacrament with the superficial coverings of artificial and inefficacious religion. It was this false and pacifying unity in the Eucharist along with the Catholic Church that Católicos intended to protest.

In this regard, Católicos was also in line with Christian scriptural tradition, which condemns worship that tolerates oppression. The God of Israel and Jesus Christ prioritizes right relationships, the establishment of justice, and defense of the poor over surface-level rituals that permit oppression to continue under the guise of devotion. Indeed, the establishment of justice, in the Judeo-Christian tradition, is a prerequisite for right worship. The Hebrew prophets consistently demonstrate the ire of God against the religious customs of the unjust. Isaiah 1:11–17, for example, says that sacrifices carried out by the unjust are an “abomination” that God “hates” (ESV). The solution for a sinful people is to “Wash yourselves; make yourselves clean; remove the evil of your deeds from before my eyes; cease to do evil, learn to do good; seek justice, correct oppression; bring justice to the fatherless, plead the widow’s cause.” In Isaiah 58:4–8 (NIRV), God calls those who fast to “set free those who are held by chains without any reason. Untie the ropes that hold people as slaves. Set free those who are crushed. Break every evil chain. Share your food with hungry people. Provide homeless people with a place to stay. Give naked people clothes to wear. Provide for the needs of your own family.” Amos 5:21–24 (ESV), likewise, shares God’s perspective on right worship: “I hate, I despise your feasts and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies. . . . Take away from me the noise of your songs; to the melody of your harps I will not listen. But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.”

In the New Testament, Christ continues the Old Testament prophetic call for just worship when he exhorts his disciples to make their relationships with others right before they present their sacrifice in the temple (Matt. 5:23). In the Catholic liturgy today, this tradition ideally continues through the reconciliation Christians offer during the sign of peace. Without true reconciliation and the establishment of justice among believers from different socioeconomic backgrounds, however, Holy Communion is a farce and a meaningless ritual rather than the demonstration of self-sacrificing Christian solidarity and love. In 1 Corinthians 11, Paul excoriates the fledgling Christian community for their unworthy and unjust participation in the Eucharist. While some were stuffing themselves and getting drunk on the Lord’s Supper, others were going hungry and excluded from the feast. Unity in the believing community and true sharing in the body of Christ, Paul makes clear, depend on each member receiving their share of the communal meal. Divisions in the body of faith that exclude some from the abundance of the meal are an obstacle to the eucharistic celebration. Injustice leads to wrong worship.

The leadership of Católicos ultimately determined that the intrusion at Mass would force the diocese to recognize the injustices present and then take action. The church where the Mass was being celebrated had become a barrier of division between the races and social classes, a fact that no eucharistic theology could cover up. Católicos patterned their action after the example of Jesus Christ, who, according to Católicos “was one of the most radical and militant men of his time. He threw out the merchants, money lenders, and changers out of the holy temple. He chased them out with a whip. He chased them out because he cared enough about his religion and Church.” By envisioning their protest as a part of the mission of Jesus Christ, Católicos intended to “chase the money-lenders from that beautiful, beautiful temple”21 and restore the Catholic Church to the poor, to whom it belonged.

The night of the protest came and Católicos held their protest outside the church as they planned. Católicos described the crowd as having, alongside student activists, “Women, children, and innocent bystanders . . . not white, rich, and tuxedos they do not own . . . Christian Catholic, and relentlessly concerned for the poor and the Chicano . . . they are raza, raza, rasa!”22 The poor, who are the heart and priority of God’s work as revealed in Jesus Christ, had gathered to prophetically call the church in Los Angeles back to eucharistic fidelity and authentic community.

When the protesters arrived at the church, however, they found the doors locked to them. As they began a chant calling on Cardinal McIntyre to “let the poor in,” a group of nearly a dozen leaders of the protest entered the church through the basement and came up to the vestibule through stairs in the back, where they intended to open the doors to the activists who were chanting outside. Instead, the Católicos leaders, who had been public with their plans to interrupt the cardinal’s Mass, were met by undercover security officers, dressed as ushers, who sought to prevent those who had entered the church from opening the doors to the other activists. The encounter turned violent. Cruz remembered how, “in the twinkle of an eye, (the ushers) viciously beat upon us and attempted to eject us.”23 As the cardinal’s Mass concluded, the congregation ignored the ruckus behind them and sang the ironic words of “O Come, All Ye Faithful.” The Los Angeles police arrived shortly in full riot gear and took dozens of Católicos protesters into custody. The cardinal, seeing the pandemonium and growing increasingly upset because of the trouble at the back of the church, called the protesters a group of rabble rousers and compared them to the crowd that crucified Jesus.24

At first glance, Católicos’ action seems like a failure. They were unable to make their way to the front of St. Basil’s to present their demands, and the congregation seemed hardly troubled by their shouts of protest and arrests by police. The legal proceedings and trials that followed the protest consumed the energy of the Católicos leadership, preventing them from effectively carrying out further protests. In the weeks after the melee, diocesan leaders condemned Católicos as a new form of “barbarism” and called its leaders “militant revolutionaries.”25

I would suggest that in this final insult, however, the success of Católicos may be more visible than it first appears. The activists had faithfully followed the example of their leader, Jesus Christ, whom they saw as a revolutionary with a radical commitment to the poor and suffering in the world. Like him, they got the attention of the governing authorities and caused a commotion on behalf of the disenfranchised. They revealed to the Catholic Church its ongoing failure to become a true eucharistic community that becomes real to the world through its establishment of solidarity with the poor. As a minority community calling the Catholic Church to right worship, Católicos embodied the biblical prophetic impulse and challenged the church to do right toward its most vulnerable members.

As a radical group of Chicano activists striving to transform the Roman Catholic Church, Católicos was part of a broader movement of Chicano Catholics that would go on to successfully change the Catholic Church’s relationship with Mexican Americans. Groups such as PADRES, an organization of Chicano and other Latino priests, and Las Hermanas, a movement formed to bring attention to the needs of Chicana and Latina women, would wield immense influence at institutional levels of the Catholic Church for years to come. Through the 1972 establishment of the Mexican American Cultural Center, a training site dedicated to Catholic ministry for the Mexican American community and the development of Mexican American spirituality, and the Encuentros, a series of grass-roots meetings intended by the Catholic hierarchy to provide a forum for the Mexican American and broader Latino communities to express their concerns, the activist impulse embodied by Católicos became institutionalized in the Catholic Church’s local, diocesan, and national structures and pastoral practices. Though the explicit impact of Católicos’ protest was short-lived, the group was part of larger movement that successfully brought about long-standing and systematic change to the Catholic Church in Los Angeles and around the country.

- For a detailed description of the protest, see Mario García, introduction to Chicano Liberation Theology: The Writings and Documents of Ricardo Cruz and Católicos Por La Raza (Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt, 2009), xxi– xxvii.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, sec. 1324 and 1325, http://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p2s2c1a3.htm.

- Luis D. León, The Political Spirituality of Cesar Chavez: Crossing Religious Borders (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2014), 99.

- Gastón Epinosa and Mario García, Mexican American Religions: Spirituality, Activism, and Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 126–27.

- See, for example, Rodolfo Salinas, “Of the Church,” in Chicano Liberation Theology, 7–9.

- Richard Cruz, “The Church: The Model of Hypocrisy,” in Chicano Liberation Theology, 27.

- García, introduction to Chicano Liberation Theology, xv.

- See Cruz, “Catolicos Por La Raza and Mexican Americans Part Two,” in Chicano Liberation Theology, 22–23; and García, “Religion and the Chicano Movement,” in Mexican American Religions, 134.

- Cruz, “The Church and La Raza,” in Chicano Liberation Theology, 24.

- McNamara quoted by Mario García, introduction to Chicano Liberation Theology, xx; and Cruz, “The Church and La Raza,” 25.

- Cruz, “The Church and La Raza,” 25.

- García, introduction to Chicano Liberation Theology, xix–xx.

- Cruz, “Por La Raza and Mexican Americans Part One,” in Chicano Liberation Theology, 19.

- Ibid., 20.

- Segundo, “Utopia and Prophecy in Latin America,” in Mysterium Liberationis: Fundamental Concepts of Liberation Theology (New York, NY: Orbis Books, 1993), 328.

- García, introduction to Chicano Liberation Theology, xxii.

- Ibid., xxi–xxii.

- Cruz, “Join Us for a Christmas Eve Candlelight March,” in Chicano Liberation Theology, 52.

- Balasuriya, The Eucharist and Human Liberation (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1979), 2.

- See Balasuriya, The Eucharist and Human Liberation, 50–51.

- Cruz, “The Church and La Raza,” 25; Cruz, “Part Two: The Origins of Católicos Por La Raza,” in Chicano Liberation Theology, 23.

- Cruz, “No Room at St. Basil’s for Chicanos,” in Chicano Liberation Theology, 53.

- García, introduction to Chicano Liberation Theology, xxiv–xxv.

- Ibid., xxvi.

- Ibid.