A Meditation on Tarot

The heavens speak, dear reader.

Their celestial communication, though, often falls on deaf ears, unwilling hearers, and naive poets unattuned to their voice. Psalm 19:1–4 spells out this situation: “The heavens declare the glory of God: and the firmament sheweth his handywork. One day telleth another: and one night certifieth another. There is neither speech nor language: but their voices are heard among them. Their sound is gone out into all lands: and their words into the ends of the world.”[1]

But we are not idly interested in the declarations of the heavens, the content of the divine handiwork. Some of us pray many times a day that God’s “will be done, in earth as it is in heaven.” We desire that it will be below as it is above without knowing how exactly it is above in the heavens. What is it like in the kingdom up there? How do the waters above and below the firmament differ? What sets the heavenly realm apart from the terrestrial realm?

The speech of the heavens is dramatized in the images of three tarot cards we will consider together: the Star, the Moon, and the Sun. The Star will show the relationship between above and below in the imagery of water and light. Our way forward will begin to appear through the practices of prayer and poetry. The Moon makes more explicit our failure to hear God speak. Friedrich Schiller will help us understand this problem and begin to formulate more explicitly its resolution through the poet. That is, we see in the Moon the human afraid and helpless before the Absolute, and these cards, themselves letters of a kind, show the need for a poet who can here and now listen to the Absolute and speak its words in our words. Only a poet engaged in the play of above and below can show us a way forward. Then, the Sun shows us just what such a poet does. Here we will see an appropriate Word spoken, and one whose meaning we will need to speak again and again.

The difficulty in hearing the heavens speak raises questions at play in all kinds of communication. We are struggling with this issue right now as I try to express myself to you in a way that you might be able to understand. We are faced with the same conundrums of heavenly speech here below. We are attempting to move through what Günter Bader calls the “palindrome of thought”: spirit and letter, letter and spirit.[2] Spirit passes into letter and back again in its reception—the waters from above flow into the waters below, the celestial speaks in our hearts even when our heads cannot grasp it.

If we do not wish to stand deaf before creation, then some training is necessary.

This training is just what I propose to walk us through in this letter, which is itself a letter about a set of letters. The letters are the anonymous work Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism.[3]

ON TAROT

Tarot has regained prominence in recent years with a flurry of guides to the cards and new versions of the cards themselves. The turn to tarot manifests a desire for meaningful symbolic communication in our lives, the desire to see order and meaning in the shape our lives take. The cards and their symbols lead us into a place where spirit communicates to those who come to the cards to find pattern. The explosion of specialized decks representing various identities and subcultures speaks to this necessary human desire to find ourselves reflected in cultural myths and patterns. Recent books like Tarot for Change by Jessica Dore and The Contemplative Tarot by Brittany Muller avoid delving deeply into the possible divinatory uses of the cards in order to present the cards in just this way. Dore sees the attention given to tarot as a way to integrate creativity and philosophical reflection into more scientific forms of psychology. Muller, for instance, highlights the “New Age focus on tarot as a tool for self-development” and use of tarot “as a psychotherapeutic device.”[4]

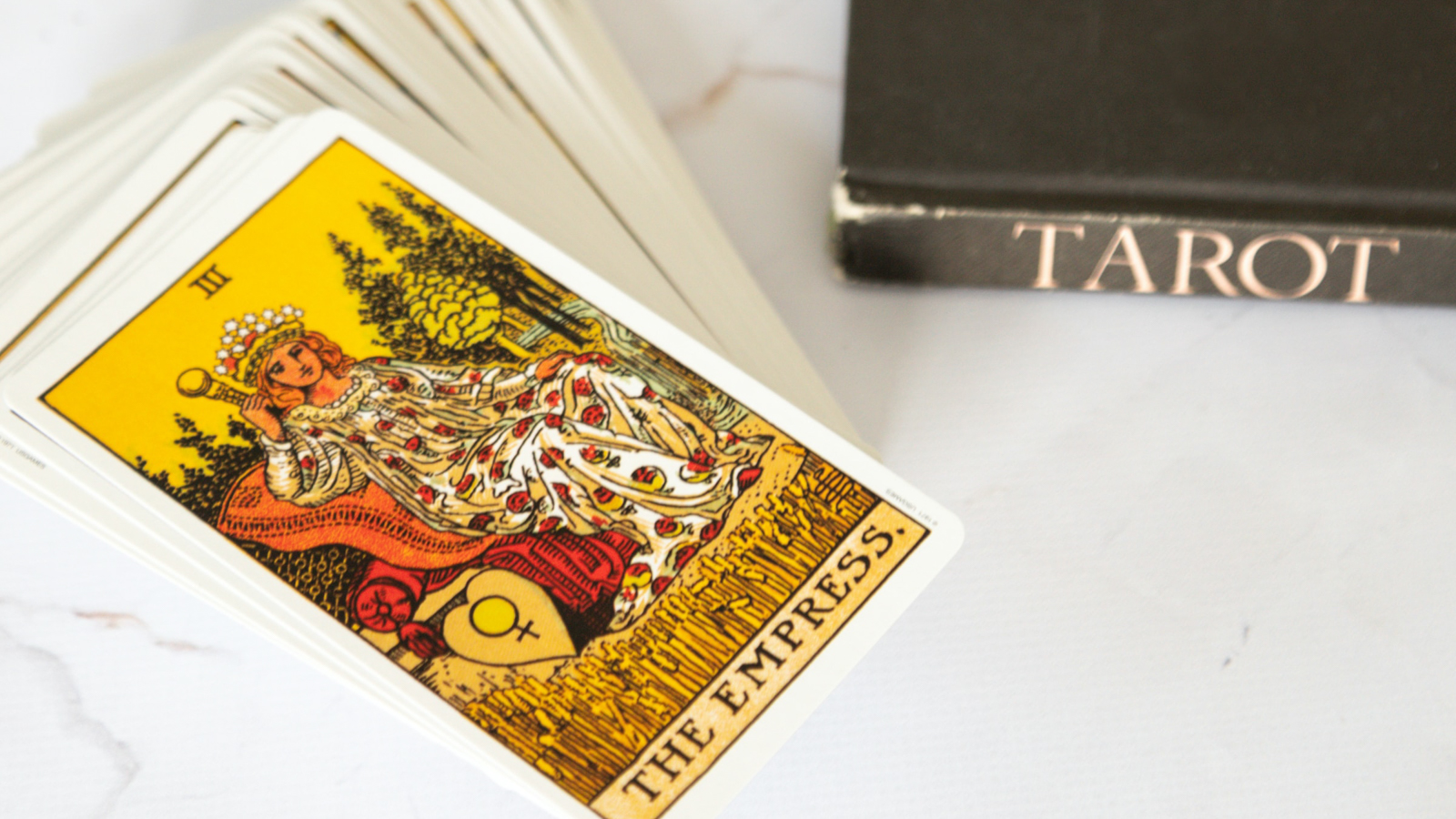

Although there have been many esoteric and hermetic accounts of the origin of the cards, we will assume that the standard historical account is correct. They began as playing cards in Italy before spreading around Europe. The symbolic use of them came later, as people began to look for deeper symbolism in the cultural artifacts they inherited. The initial flowering of this search came in France in the eighteenth century with Antione Court de Gébelin’s Monde primitif, analysé et comparé avec le monde moderne and Éliphas Lévi’s investigations into the magical potential of tarot. The full shift away from playing cards to something more revelatory occurred in the English-speaking world with the popular publication of the Rider-Waite-Smith tarot deck. Rising from the symbolic understanding of A. E. Waite, the deck was illustrated and made visible by the hand of Pamela Colman Smith. The French school, exemplified in our anonymous Meditations, looks to the Marseille tarot deck whereas more recent commentaries have turned to Smith’s images. We will keep them both in mind as we move through some of the cards.

Our use of the cards will not depend on the reality of any of the legends about them but will assume they retain a certain spiritual power. Dore names this power well: “Tarot, as you’ll see if you have not already, provides a path toward reclaiming the imagination from the grips of doubt and rationalism. Toward reawakening the part in us with the audacity to know without material evidence.”[5]

Setting aside, then, any predictive power of the cards, I will take up the progression of three cards for the sake of investigating what it might be like to hear the heavenly communication and then to speak it ourselves. Meditation on the cards is a spiritual exercise that simultaneously forms and communicates the cards’ meaning to those who give them their attention. All three—the Star, the Moon, and the Sun—are major arcana of the tarot. The major arcana are the twenty-two cards with numbers and names, but they are not given a suit, like wands, cups, swords, or pentacles. These major arcana tend to be more symbolically rich and allegorical than the minor arcana. The term comes from the Latin arcanus, which invokes a sense of secret and mystery. The major arcana speak to those who are willing to listen, to wait on their secret, their arcane meaning. My task here is to use the cards as a guide for the sake of uniting the waters above and the waters below.

THE STAR

We begin with the Star. The seventeenth major arcanum of the tarot, the Star features a nude woman on the edge of a body of water, pouring out two pitchers of water into the larger body. A constellation of eight stars rises behind her—seven smaller stars around a large central star. A bird perches in the leaves of a tree in the background. The Star can represent our initial state and our current toil as we stand beneath the well-ordered heavens with our work on the waters below the firmament. To see what the card wants to tell us, or, better yet, how the card invites us to contemplate or wrestle with what we see, we first need to grasp the meaning of water.

There is a connection between the waters above and the waters below, and that connection makes sense when we take the waters as symbols of life that signify sustenance and transformation. Water, moving, nourishing, labile, and indivisible, represents the necessary aspects of created life that are not easily captured, quantified, or left behind. How easy is it to hold water in the hand? How difficult to cut when it is not frozen? The uncontrollable character of water—think of a pipe burst in a home—cannot be separated from the fact that we require water in order to live. The uncontrollable and unnameable is what gives us life.

In Genesis, we are told that God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters,” and then “God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so” (Gen. 1:6–7). God clears the space for creation by pushing the waters above and below. Here below, we often take water as a place of chaos, even if it is the material through which God’s will can be actualized in creation. We know that the waters carry God’s will because this is precisely the function of water in the heavens. The waters above move and act according to God’s will. They do not err in their correspondence to God’s desire. The stars, as the constellation of the card, move in good order. These are the celestial intelligences responsive to the word of God.

We desire the heavenly order here below because in heaven all things move in harmony and divine pleasure. The waters above mark out the space of heaven where the will of God is done in creation. The workers—waters, stars, all celestial powers—of this will do so spontaneously and instinctively. God does not give commandments to the clouds or the stars in the form of written words. They do not deliberate. They act.

In the very same way, water names in us the parts of us that do not deliberate and calculate but give spontaneous shape to life. In the same way that the water goes into the roots of the plant but does not deliberate about how it nourishes the plant, the tarot card illustrates how the water in us also pours itself out in spontaneous nourishment. Water gives height to plants and nourishes the unknown child in the womb. Water, moving and unpredictable, is also what drives us to movement. The vision of the Star, according to the Meditations, is our attempt to see our biological growth and spiritual growth in tandem so that we find “their intrinsic kinship . . . their fundamental identity.”[6]

The relationship between what is above and what is below, their constant parallel, is made clear for Christian readers in the prayer given by the Lord. As the kingdom arrives, so the earth becomes like heaven. Our prayer is that the water below may be as the water above. As below, so above.

The stars obey without thought and so are without morality and responsibility. The souls here below, however, act with intention and response: we are inescapably moral and responsible in our response to God. We are more than animals in that we have been made like our God, creators, and we are all tasked with the work and the act of self-creation, of finding a life that forms a cohesive trajectory. But it is here, at this level of self-formation and self-creation that we fail. The heavenly waters move as one while we pour from our vases into the greater water of terrestrial creation.

The arcanum of the Star is the beginning of a trajectory, a meditation, or a spiritual exercise toward the transformation of the unknown, the future, into the project of the kingdom. The Meditations describe this card as one centered on hope—the hope of the ideal, the kingdom in heaven, becoming the real, the kingdom on earth, through the alignment of our “lower water of instinctivity” with the water or sap of “growth, progress, and evolution.”[7]

The unity of these two aspects of the person, our lower water and the celestial water above, begins in prayer, the cry of the beating heart to the unchanging God. True prayer does not demand its way from God. It cries out that God’s will should dwell in our heart: the two waters should be mingled just as they are mingled in the woman pouring, the flowing of blood in the cause of creation. Prayer is, then, a kind of magic in which the human being gives itself over to God and in which God is the agent of action. Prayer calls for a miracle and our continual circulation of water is a statement of hope. As the author of Meditations puts it, “A miracle is the descent of hope, i.e. the ‘higher waters above the firmament,’ into the domain of continuity, i.e. the ‘lower waters beneath the firmament,’ and it is the action of the two ‘waters’ united.”[8]

The distance between the waters is a moral fact of our lives: things are not as they should be, and the kingdom does not stand around us. We are not as stars, but we should be. The solution lies not merely in poetry or the imaginative reconciliation of the waters but in a poet who reconciles. As our anonymous author explains, “The poet is the point at which the separated waters meet and where the flow of hope and that of continuity converge.”[9] Tellingly, the woman pouring the water, working to unite the waters, does so while looking down to the earth and its terrestrial water. She works in vain without the contemplation of the heavens, the higher things, that lead to the miracle of the union of heaven and earth.

Jesus of Nazareth knows nothing of the distance between the waters. The living water, the womb of the kingdom, flows from within him. Jesus brings the kingdom as a poet who lives and speaks from God’s will as communicated by the heavens. His poetry makes what is above as it is below. The stars move as water and blood move through the woman.

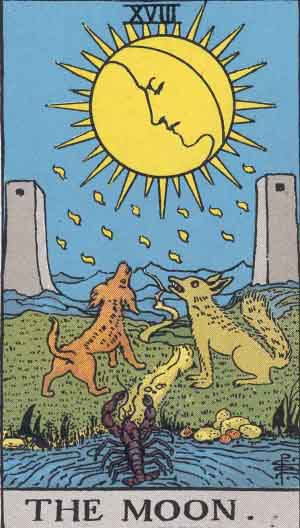

THE MOON

The cards represent the next step in the journey of creation and appropriate human poetry, the coming of the kingdom, with the Moon. While the card will again show us our failure, it guides us toward reconciliation. The top of the card is marked by a moon that is in the middle of its eclipse, a point of darkness. In the middle of the card, two animals that are framed by two towers bay up at the moon. Depending on the deck, the two animals are either wolves or a dog and a wolf. A crayfish makes its way toward the animals from out of a pool. The author of the Meditations points out that while the water of the Star was at least flowing, on this card the waters are almost stagnant and not connected to the sea. The card, the author suggests, picks out a problem of neither the interior nor exterior life, the temptations given in the previous arcana, but of a constraint imposed on human beings by virtue of our incarnation.

The difficulty named by the card, then, is our difficulty as embodied creatures to reflect heavenly lights. Just as the moon’s reflection of the sun is hindered by the earth, our “materialistic intellectuality” dominates our intelligence and misshapes how we form our life. The Moon in eclipse reflecting the human face is an image of this darkness produced by our narrow desires.

The failure is the failure of the lower waters to reflect the higher lights. We have only the dark illumination of our wills, our matter. The arcanum does not just propose our failure or point it out to us—law without gospel—but it also offers a spiritual exercise, “an event—that of opening eyes, i.e. the opening up of an inner sense which permits things to be seen in a new way.”[10] The way to be opened is the way that is here rejected by the crayfish that stands on the edge of the water before the beasts. The small crayfish sits in the waters of the earth, the waters of our material, emotional, and affective self. It remains at home and yet mute in this womblike water on the edge of the earth with its terrifying beasts and reflected light. All that pulls it forward is the faint tug of the tidal power of the eclipsed moon. What should be our point of contact with the higher light, the power that gives order to the higher waters, is occluded so that we might come to grasp what makes us different from the stars. The card is the “Arcanum of intelligence with conscience eclipsed.”[11]

The possibility opened up in the previous card, of our inner instinctivity reaching toward God, is covered over in the movement backward by the crayfish into the water. The small animal is faced with the difficulties of finding a way between the two howling animals to the source of reflected light, and when faced with this difficulty it begins to retreat away from the journey to the light. Likewise, the card asks us to consider why we move away from the object of our true desire. We have long grown accustomed to focusing on results, on effects, and on the seeming satisfaction of our desires. We aim to consume rather than to produce, to be created rather than be creative. Our intelligence is trained in cause and effect, profit, and productivity, and so we live in a seemingly unending time of harvest—a forever stagnant autumn. The crayfish has something to eat in its small pool after all.

The crayfish, and we are often these crustaceans, does not listen to its conscience and so lacks any intuition it can follow. Friedrich Schiller describes the step the crayfish refuses: “It is, as we know, through the demand of the absolute (as that which is grounded upon itself and necessary) that reason makes itself known in man. This demand, since it can never be wholly satisfied in any single condition of his physical life, forces him to leave the physical altogether, and ascend out of a limited reality into the realm of ideas.”[12] Schiller analyzes the problem of the crayfish before the distant reflected light, the Absolute, and the agony of the hounds. The animality of our humanity works its way toward the Absolute as it grapples with the fact of our specific determinate existence and our ability to discern the universal in the law of our life: we know ourselves to wrestle with a greater power.

Schiller maps out this tension in terms of different drives operating within us. The sense drive wants to be determined, “wants to receive its object.” The desire of this drive is for the effect and the final product. The sense drive is passive without any autonomy. It simply takes in what is there and acts upon instinct. Here is our instinctivity without any modifications—pure earthly water. The other drive is the form drive that desires “to determine, to bring forth its object.”[13] The form drive sees the lack of the kingdom, the call of the Absolute to act, and the discrepancy between justice and the present. The sense drive begs God for bread and the form drive demands that the kingdom come.

These two drives remain unreconciled even in the reflected light of the Moon. The stars above work as they should entirely from their instinctual nature. For that reason, though, they are incapable of responsibility and morality like those of us below. Stars are amoral while moral human beings are inescapably responsible to our conscience. The difficulty presented by the crayfish is, then, our attempt to reconcile the animal instincts of our nature with the demands of our morality, to find our freedom to act here and now as our response to the communication of God. To be free, to reconcile these two tendencies, would be to find our prayers answered in the present by what God does in us. Likewise, Jesus describes freedom in the given moment, in the hour at hand:

Now my soul is troubled; and what shall I say? Father, save me from this hour: but for this cause came I unto this hour. Father, glorify thy name. Then came there a voice from heaven, saying, I have both glorified it, and will glorify it again. The people therefore, that stood by, and heard it, said that it thundered: others said, An angel spake to him. Jesus answered and said, This voice came not because of me, but for your sakes.

(John 12:27–30)

Jesus has united the drives to form and sense in his grasp of his vocation. He knows absolutely the demand of the Absolute; his instinct and the demands of the moment are at one rather than in tension.

This release of the tension between drives occurs in their union in what Schiller calls the play drive that “will endeavor so to receive as if it had itself brought forth, and so to bring forth as the intuitive sense aspires to receive.” Play marks the place where our instincts and our words coincide with what is given, responding to the Absolute with the move that continues the game, the dance, the play, however surprising the result. The shift is from the disposition of autumn to springtime, from the cause to the effect. “The former,” the Meditations author explains, “is understanding of that which is; the latter is participation in the becoming of that which is to be.”[14] The archetype of the person of springtime is Abraham, who went out of Ur through the travails of the desert—the hounds—to heed the call of the Absolute in his time and place. He remains a spring to those who go to him in faith to be a new sort of person.

The Moon shows us that we must move forward, must follow our intuitions, if we are to reach the kingdom and our God in this time and place. We must move out of the Ur that traps us in the rope of conventionality in order to enter the winter that leads to spring. The goal is, again, a poetry appropriate to our life: the union of the waters in our person, the unity of our own creativity within creation. The way to freedom is play—that is, putting the call of the Absolute into play in this material world. Freedom comes when we take our place in the making of creation. Or, as Jesus says, “If the Son therefore shall make you free, ye shall be free indeed” (John 8:36).

THE POET

Before we consider the significance of the third card, I must say a few words about poetry, the appropriate naming with the appropriate word. Jesus himself is a poet in this sense, and he leaves us words to set us free. Poetry is not self-indulgent but rather serves as an index of our morality by indicating our ability to perceive the world around us. Do we see the world as the place where we respond to God in all things? Do we see the mountain in terms of mineral rights, or do we see that it melts like wax before the Lord? The right word or concept for the world around us leads our response to it. We respond differently to a person who is our friend or lover than we do to an enemy. We live differently in the world as a place to be used than as a place to be inhabited. Poetry expands our moral horizon by providing the playful word to continually engage and define our reality.

Tarot demonstrates the impact of the flow of the heavenly and earthly water on our response to the power at work above us. It shows us the progress of the earth on its way to heavenly movement, and it enables our moral and poetic engagement in this time and place.

The tarot images are not fanciful. They name the work of the moral life as it is to be interrogated in modernity. This perennial struggle, from autumn, through the winter, and to the spring and summer, is to see what is and take our part in what is to be. It is a pressing need for intuition, an inescapable desire for the appropriate word or action.

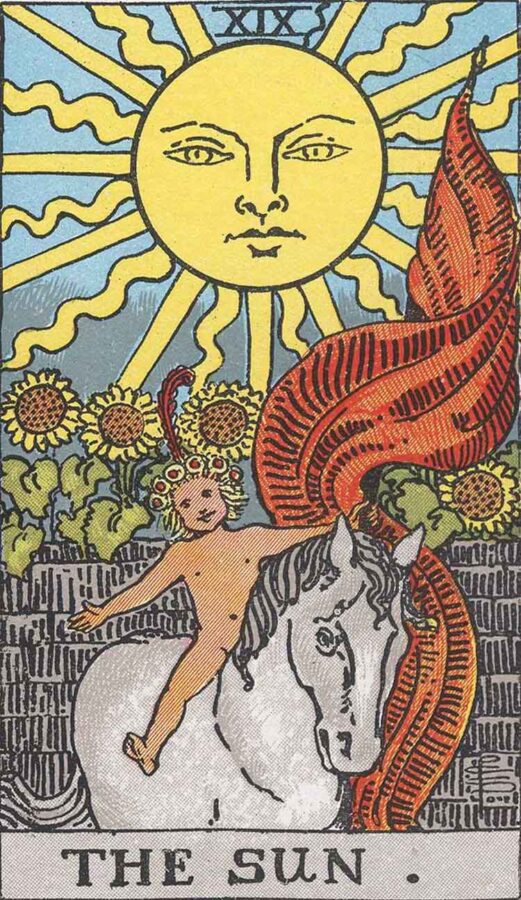

The Star has shown us that the heavens speak. The Moon has shown us how we hear the voice of creation but fail before the beasts that block our way. Next, the Sun shall point us to the place where the celestial and terrestrial light meet, where the waters become one.

THE SUN

The images of the cards diverge when it comes to the Sun. The Marseille deck depicts two children together before a sun that pours down its rays. The eclipsed face of that sun may be the same face that we glimpsed earlier in the Moon card. Conversely, in the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, a single child is surrounded by sunflowers; that child rides a horse and carries a flag before its sun. The question for us is whether these differing images communicate a difference in thought. In the palindrome of thought, can the same spirit pass through different letters?

Let us begin with the Marseille card. Again, remember that the card is meant to produce a spiritual exercise, a form of meditation that can occur as the card communicates its meaning. The card shows us two children united beneath a dark sun. What might be intuited at this point? They appear to reach out for each other, one for an embrace around the neck and the other for an embrace about the heart. The double image forms a center for our thoughts to circle. The midnight sun unites the heavenly light of the star with the reflected light of the moon in a single being that burns with original and reflected light. The divine light of the heavens and the terrestrial light of our human intelligence meet in this sun. The union envisioned by Schiller and the morally necessary intuition coincide in this poetic word.

The union is not only that we find the right word for the poem, though it is that. The union is also in the hearing of the word of creation, the listening to the great spheres, the acknowledgment of creation’s speaker. The midnight sun is our way to finally perceive creation at last, a perception reflected in the way the children reach forward in innocent embrace. The right word of and for creation creates the union of humanity. It shows us a word that can communicate what we sense as well as what we think, a word that can be heard by others. We say the Word in the conversation of our life together, and the other knows our sense. They feel it too. The palindrome of thought, spirit to letter and letter to spirit, is completed between the heavens and us. The waters above flow freely in us, and they flow freely between us. We live in a created world together at last.

The Rider-Waite-Smith deck gives us the Sun undarkened and a jubilant child astride a horse. But the message remains the same. The sun pours forth its light to a creation that joyfully receives it in the blossoming flowers, the power of the horse, and the joy of the child. The child is the earthly reflection of the Sun, the place in creation where all can be embraced and engaged and loved. The card places us in the place of the child who reaches out for the heart and the embrace of its fellow gazing at the card itself. Here is the child, the poet, who can connect all things in the light of the heavens—“all things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life; and the life was the light of men” (John 1:3–4). The card demands that we take it as addressed to us. The image suggests our movement to the heart and to the center of creation and in that way coaxes us into the exercise of our intuition. It asks us to see it all together—the sun, the earth, the animals, the plants, and our fellow human beings—and to embrace everything. Here is the movement from “an understanding of what intuition is to its exercise” through the arcanum of the card opening out to all of creation, the parched earth opening up to the rains from above.[15]

THE POURING OF BLOOD AND WATER

The cards, whatever magic we do or do not attribute to them, make us aware that the heavens speak. They drive us to wonder about how we might hear the words from above. What do we even mean when we ask that it be here as it is above? How do we make the old incantation “as above, so below” into a prayer? We need human words that can be the words of the heavens all over again, a prayer that repeats the heavenly spirit in our own spirits. As the world burns, as the heat prepares to boil some of us alive, and as the waters dry up around us, we see that the need for the poetic word, for the word that expands out to our whole world, is a moral demand. Our quest for the playful word that can be sent around to bring out our spirits and so unite our senses and our intelligence is a moral responsibility. The words we have used up until now—let us invoke only the dark magic of capital—bring destruction rather than embrace. They push the heart far away from us, the heart of God, and our fellow human beings.

In this letter, I have tried to communicate through these letters the spirit that passes through creation into our spirit. In this middle time between creation and end, we find ourselves pursuing the stringency of moral realism. The Kantian wind upon our fire, we chase the fecundity of myth and symbol, the productive ambiguity of the cards. By entering into that ambiguity and symbolism, we can come to a sense of moral realism: our prayers to God can become the directives of the kingdom.

I cannot perform your intuitions for you. You must do that. You must find the word that opens up the heavens. You must find the way wherein you can drink the heavenly waters. You must do the work of uniting the firmament and the land below.

Let me leave you with two images. First, a word from Revelation:

And he shewed me a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God and of the Lamb. In the midst of the street of it, and on either side of the river, was there the tree of life, which bare twelve manner of fruits, and yielded her fruit every month: and the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations. And there shall be no more curse: but the throne of God and of the Lamb shall be in it; and his servants shall serve him: And they shall see his face; and his name shall be in their foreheads.

Revelation 22:1-4

The river flows from the throne. It feeds the nations. It gives us his name. Here, there is only one water, one humanity, and there is enough to eat.

My second image is from John: “But when they came to Jesus, and saw that he was dead already, they brake not his legs: But one of the soldiers with a spear pierced his side, and forthwith came there out blood and water. And he that saw it bare record, and his record is true: and he knoweth that he saith true, that ye might believe” (19:33–35). The Word pours himself out on the earth. Creation is hallowed with the celestial water and the blood of God. The heavenly water comes through sacrifice, his death flowers in the opening of his wound. He completes his prayer, and his work in his dead body just as he willed it to be.

Jesus casts his spirit out in the words of blood and water. What do we hear, and how do we reply?

[1] The Psalms are taken from the Coverdale Psalter. All other biblical translations are from KJV.

[2] Bader, “Spirit and Letter—Letter and Spirit in Schleiermacher’s Speeches ‘On Religion,’” in The Spirit and the Letter: A Tradition and a Reversal (London, UK: Bloomsbury, 2013) 131–53.

[3] See Anonymous, Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism, trans. Robert Powell (New York, NY: Penguin, 2002).

[4] Muller, The Contemplative Tarot: A Christian Guide to the Cards (New York, NY: St. Martin’s, 2022),18; and Dore, Tarot for Change (New York, NY: Penguin Life, 2021). Dore’s book engages in this psychotherapeutic reading as well. Her work is exceptional as a current engagement with the secrets of the cards and the translation of their meaning.

[5] Dore, Tarot for Change,3.

[6] Meditations,469.

[7] Meditations,469.

[8] Meditations,472.

[9] Meditations,469.

[10] Meditations,479.

[11] Meditations,477.

[12] Schiller, Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man,trans. Elizabeth Wilkinson and L. A. Willoughby,in Schiller, Essays,eds. Walter Hinderer and Daniel O. Dahlstrom (New York, NY: Continuum, 1993), 126.

[13] Meditations, 469 and518.

[14] Schiller, Letters, 126; and Meditations,502, italics in the original.

[15] Schiller, Letters, 126.