Dystopian novels—stories of the future going badly wrong—have apparently now surpassed the vampire and fantasy genres in the young adult fiction market. The books, and the phenomenon of their popularity, have provoked numerous discussions online, in schools, and in the sort of serious, adult magazines that teenagers don’t read. (We know this, of course, only because we read about it in the New Yorker.) Some reviewers have interpreted dystopias written for and read by young people as social commentary, focusing almost exclusively on adult-generated problems such as war or oppressive states. But it seems important for teachers and pastors to think through ways that young adults of a book-buying economic class bring the story into the mess of their own day-to-day striving and loving. In this conversation, Kara Slade, a student in theological ethics and former Duke faculty member in mechanical engineering, and Rev. Amy Laura Hall, a United Methodist elder and associate professor of Christian ethics at Duke Divinity School, discuss how young people read and employ these popular books, particularly the Hunger Games series.

Kara N. Slade (KNS): The pressure to succeed in a hypercompetitive environment, to be the future, can become a heavy burden when borne in isolation. I remember that burden myself. In 1990, I arrived at Duke as a freshman with a trunk full of new clothes, a heavy accent, and a completely falsified air of self-confidence. My parents rode the wave of New South prosperity from Depression-era childhoods to the yacht club, and I was painfully aware of both the requirements for success and the consequences of failure. Although the economy of the South had changed, the moral imagination of many southerners had not, and so the rhetoric of familial honor and shame formed much of my moral vocabulary. Failure was out of the question—I needed to win. Duke offered me a chance of winning, and today it makes that offer to others. Its main website features a slide show of smiling students and energetic professors, accompanied by a series of assertions of institutional confidence: “Outrageous Ambitions,” “Research that Changes Lives,” ”Inquiry across Disciplines.” It is a place where outrageous ambitions become success, where children of promise learn how to win. That, at least, hasn’t changed in twenty years.

Amy Laura Hall (ALH): That pressure to be the future is intense. The best trick in my bag, when teaching Duke undergraduates, is to have them watch the film Gattaca and then ask with whom they identify. Each time, we have talked through how they variously feel like all three: the son who is genetically engineered to be perfect; the son conceived by “faith” who is replaced by his genetically superior younger brother; and the son who was perfect, but who, through a non-genetic incident, has become imperfect. Many of my students know they are supposed to fulfill the dreams of their elders, but they have a sense that they are (a) not fully up to the task and (b) straining their friendships and stifling their creativity by living into the struggle of competition. It was heartbreaking to realize that even their voluntary associations, like fencing or choir, morph easily into occasions for padding their job applications.

I am now learning to use Harry Potter also. We talk about the ways that the Death Eaters, the dark wizards and witches who oppose Potter and his friends, distinguish between pure and impure. We talk about how the Death Eaters exploit a culture of fear to enlist the authorities to justify torture and other less overt forms of social control, like shame. The conversations between first-generation immigrant students and the WASP students can be intense, as they compare notes about their elders’ expectations and their own fears of inadequacy.

Figure 1. Advertisement for The Day After (left) and Federal Civil Defense poster (right).

Government rhetoric in the early Reagan era emphasized the survivability of a nuclear attack, with extensive plans made at the federal level for continuity in services such as postal delivery, so that “those that are left will get their mail,” and the clearing of checks, “including those drawn on destroyed banks” (New York Times, August 15, 1982 and Newsweek, April 26, 1982). Meanwhile, The Day After graphically portrayed a post–nuclear war America as a near wasteland filled with the dead and the dying.

KNS: At the same time, there are some differences between our undergraduate days and today that can’t be overlooked. The future I expected as I looked toward graduation was a product of its own time, and that time has thankfully passed. My generation’s prevailing fear for the future was that there would be no future at all, for anyone. The threat of large-scale nuclear war with the Soviet Union was on our screens as well as on our minds. The beloved 1983 movie War Games featured a very young Matthew Broderick as a computer geek who accidentally triggers a nuclear crisis with a dial-up modem. All ends well, as he narrowly averts the missile launch by improbably sneaking into the Air Force’s high-security Cheyenne Mountain complex with his girlfriend. The Day After, a 1983 made-for-TV film, was much less beloved but still vividly remembered. It brought images of a post-nuclear-war America to television, and it also brought mandatory-attendance discussions of inevitable and lingering death to our classrooms. If the future went badly wrong, we thought, we would all die together.

ALH: I totally remember The Day After. I think I had sex with my boyfriend for the first time that next weekend. I also remember looking at the map from one of the Stop-Nuclear-Insanity-Now-Now-Now groups, wondering where I could go to college that would be safe, and realizing it would likely be a question of dying quickly or dying slowly. And that opening scene from Terminator II messed me up, where Linda Hamilton is having a nuclear daymare in the playground. I think she quotes Stanley Hauerwas somewhere later in that movie, about men and bombs and their destructive impulses. And the list of reading for many high school kids back in those days included the basics of misery and social control: 1984, Fahrenheit 451, Brave New World, with Flowers for Algernon and Lord of the Flies thrown in to send us over the edge, I guess.

KNS: We didn’t die, of course, we just ended up with mortgages, subscriptions to the New Yorker, and a grinding sense of regret. And now, apparently, our generation is writing, publishing, and promoting postapocalyptic and dystopian fiction for young people at an unprecedented rate.

ALH: Duke undergrads started telling me about four years ago that ethics courses need to include Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games. It seems as influential these days as Harry Potter.

KNS: The Hunger Games series is probably the most visible example of the dystopian trend. It has generated sales in the millions as well as an upcoming movie version. In a lengthy New Yorker article on The Hunger Games and the popularity of dystopias in general, Laura Miller also describes other titles in the genre, a menu of authoritarian nightmares and demonic TED talks:

There are, or soon will be, books about teen-agers slotted into governmentally arranged professions and marriages or harvested for spare parts or genetically engineered for particular skills or brainwashed by subliminal messages embedded in music or outfitted with Internet connections in their brains. (June 14, 2010)

It seems that we are no longer collectively afraid that we will die together. Now we are afraid of the ways that we will come apart as a society, or may be taken apart by unrelenting surveillance, or may have interchangeable parts as bodies. It is easy to assume that young readers would follow the lead of adult authors and commentators in reading these books as future-oriented social commentary. But adult fears for an uncertain future can become a different tool in younger hands. The ways that young people read the books we put in front of them do not always conform to the marketing aims.

Miller draws a distinction between dystopias created for teenagers and those aimed at adults such as 1984 or Brave New World. Adults may need a convincing warning against a future that may be averted, but teenagers lack the power to effect change in the near term: “It’s not about persuading the reader to stop something terrible from happening,” she explains, “It’s about what’s happening, right this minute, in the stormy psyche of the adolescent reader.” To be appealing, she argues, social commentary in itself is insufficient. The characters must face disasters and injustices that resonate with young readers’ lived experience, but these characters must not be comprehensively crushed by them. Eventually, hope must enter the narrative.

ALH: Drawing on my own youth experience here, I do recall vividly the discordant combination of solidarity-via-pep rallies for West Texas football and reading assigned books that describe existence as inherently a struggle and the future as rock-bottom grim. I keep thinking of Prince’s work during this time, which may call us on a different way. Prince was giving us songs of loving solidarity; for example, in “Let’s Go Crazy,” he sang, “Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today to get through this thing called life.” Amazon.com Widgets It is relevant, I think, that Prince grew up Seventh Day Adventist. His love songs for our generation were often about solidarity and hope precisely during the worst of the end times. At the risk of stretching too far, I will suggest Prince put the book of Daniel to a sexy dance beat. Has someone argued that already in print?

KNS: If they haven’t, that sounds like a collaboration between you and Thea Portier-Young waiting to happen. It is hard to know how an artist like Prince could counter the social Darwinism going on in youth dystopias today, which brings me back to Collins’s Hunger Games series. A summary is probably in order at this point.

The government of what was once North America conducts a deadly competition between children, best described as the Theseus myth combined with American Idol as played on an Xbox by a sociopath. As one of the lottery-selected combatants explains, “taking the kids from our districts, forcing them to kill one another while we watch—this is the Capitol’s way of reminding us how totally we are at their mercy.” A few, however, are not the victims of chance but “the kids from the wealthier districts, the volunteers, the ones who have been fed and trained their whole lives for this moment.”[1] The premise may be incoherent as a spectacle of the state, but as an analogy to capitalism—or to education—it functions quite well. Some children start with advantages due to wealth. Other children—the unprepared ones, the ordinary ones—die unceremoniously, as the children with advantages temporarily band together to kill everyone else first before turning on each other. “At-risk,” indeed.

The internal monologue of the protagonist, Katniss, brings to mind the interview segments from Survivor or The Real World: “he is luring you in to make you easy prey” or “for there to be betrayal, there would have to have been trust first.” “He” is Peeta, the earnest boy from her district, who assumes at the outset that he is doomed. The nearness of death leads him to a moment of honesty and self-disclosure. “I want to die as myself,” he tells her, “I don’t want them to change me [. . .] turn me into some kind of monster that I’m not.”[2] The rules of the game change arbitrarily, and change again, casting relationships and motive into doubt. The game, and the need to win, prevails over all other considerations.

This language of competition and victory is not limited to fiction, of course. One need only spend a few minutes with Google to find a profusion of sites aimed at students who want to “win at the college admissions game” (The Ivy Coach, http://www.theivycoach.com/). A few more minutes reveals critique after critique of public education focused on the “poor performance” of the other students, the ones who are not applying to Duke or Emory or Yale, and who are deemed to lack the “minimum skills needed to compete in our economy” (Harold D. Miller, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 1, 2009). Horizontal violence in the midst of scarcity, albeit of the mostly metaphorical kind, is assumed to be an unavoidable part of adult life. We start our children early on that path to adulthood.

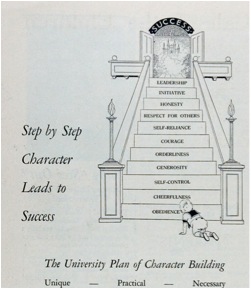

Figure 2. The path to leadership and success according to the “The University Plan for Character Building” (Parents’ Magazine, April 1929). Advertising and parenting advice used tactics of shame and fear to create a social divide between “choosy” mothers, whose children would climb the stairs of success, and other mothers who “make mistakes in training” and whose children would be led toward the merely “commonplace.”[3]

ALH: Parental desire for the “stair steps to success” (to quote the depression-era advertisement that I describe in Conceiving Parenthood) is a blood-rich vein for marketers. The generation one stair-step behind us grew up having watched their parents watch the fall of the towers, and during a time when we have become increasingly aware that, as one friend put it, “China owns us.” The sense of impending chaos and domination (whether economic or more obviously violent) is strong right now.

KNS: Economic chaos coupled with violent authoritarianism is certainly a constant presence in The Hunger Games, but the presence of television (and, by extension, television viewers) shapes the narrative more than any other factor. Suzanne Collins’s dystopian America may suffer from the minor problems of endemic starvation and a brutal totalitarian state, but maybe the clearest sign that something has gone badly wrong is that everyone watches the same program on television. It is not clear whether there is only one (government-controlled) channel, or whether the continent’s viewing habits have become strangely consistent, but in any event, the Hunger Games are must-see TV. The contestants consciously play to the omnipresent cameras in a bid for sponsors, and later in the series, Katniss becomes a potent but personally ambivalent televised propaganda symbol.

ALH: We need another conversation eventually about dystopic television. And about how viewing brutality and competition functions right now. Bookmark, for example, the new HBO series Game of Thrones, which is an obvious use of fantasy/history as potent cultural commentary. It seems to be all about fear of domination and ways to get back up on top. As far as I can tell, it is dystopia dressed as fantasy. (Is that a genre?) Tolkien fans should weigh in on this series, really, and consider how it taps into similar themes in the blockbuster Tolkienesque movies that came out right after 9/11.

KNS: In The Hunger Games, that brutality and competition is not just viewed on TV, of course. The reader also participates as a viewer of the spectacle. In a collaborative Slate piece, several commentators named a similarity between The Hunger Games and (real-life) TV’s 24. One of them, David Plotz, described the novels as a “Kama Sutra of violence” and “quite possibly the most sadistic set of books marketed to children” (August 30, 2010). It is possible, of course, that for a generation that grew up playing first-person shooters, obsessively detailed portrayals of weapons, pain, and blood are an unremarkable part of entertainment. But these books were written by an adult, and they have been embraced by adult readers. The same questions raised about 24 at our recent conference, Toward a Moral Consensus Against Torture, also, I think, apply here: do we like to watch? Do we want to watch?

ALH: That was for me the scariest part of preparing for the conference. We had been naming, as my colleague Matt Elia put it, that we wanted to turn people’s eyes in a direction that they didn’t want to go. We wanted people who have been avoiding the news about torture to face what has been done in our name. And then, speaker after speaker gently explained to some of us that many people want to watch torture, that a generation of ostensibly Christian people have specifically tuned in somehow to be turned on by displays of brutal domination. Perhaps feeling our own impotence, post-9/11, we have craved ways to manage brutality, almost like a form of cultural self-cutting? Only Christians have not been cutting ourselves, of course. We have been cutting our Muslim brothers; the April 25 Wikileaks dump of information regarding Guantanamo shows that pretty clearly. But in the comfort of our own living room or bedroom, maybe we have watched without really considering what we are watching? (Just to be clear, some of my best friends love that 24 show, and I am hoping they still love me after this conversation.) Christians in the United States are going to need help sorting through why we have been wanting to read and watch what we have been wanting to read and watch in the last decade.

KNS: In one of the notes to Works of Love, Søren Kierkegaard tells the story of a clergyman and a prostitute. In search of privacy, they duck under an archway, where she tells him, “Here you can be absolutely safe, here no one ever comes, and under this arch no one can see us except God.” For grown-ups who think that they can watch (or do) what they like but not be seen, this is a sobering reminder. For teenagers who are temporarily trapped in the high school panopticon, I hope it might also be good news. Beyond the gaze of teachers, parents, and classmates who exercise what Marilynne Robinson names as “the tyranny of petty coercion” is the God who truly sees both watchers and watched. Robinson observes that the task of “struggling out of the toils of sheer pettiness” is one that requires “first-rate courage,” but as with other virtues, courage is more easily instilled in community than in isolation. There is a “prevenient courage” required “to nerve one to be brave,” and that courage is a gift that we give each other.[4]

ALH: The fragile strands of friendship, solidarity, hope, and fine-knit abundance are at play in two other dystopias I use to teach soon-to-be professionals at Duke: Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake and Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. In both of those dystopias, young people receive and give friendship in very vulnerable and yet resilient ways. I have a quarrel with the film version of Ishiguro’s story, in that it seems to be about accepting one’s fate rather than resisting domination through solidarity and love. I think the novel can be read either way, but, to rework a Star Trek phrase, I want continually to affirm that resistance is not futile. Even if you go down struggling, nonviolently, for love, such resistance is redeemed. I will dare say that creative resistance and daily solidarity in a climate of fear and domination is a way to faithfully live into the resurrection. But that can’t be mass-marketed by InterVarsity Press or NavPress or any other major Christian outlet. It has to be daily, embodied, messy work. The revolution is not being televised or tweeted. It is happening door to door, day to day, face to face, Sunday by Sunday, and Friday night by Friday night.

KNS: The need for friends, for the networks of kinship and solidarity that help us to be brave, is as urgent for professional Christians with mortgages as it is for Duke University or Riverside High School freshmen, as they try to find their way in a bewilderingly competitive environment. Knowing that I stand before God as one who is seen in all my moments of cowardice, casual betrayal, and petty cruelty, I also know that my neighbor stands in the same place. Writing in The Epistle to the Romans, Karl Barth follows Kierkegaard in placing friendship and solidarity in proximity to the shattering apprehension of our own sin:

There is no positive possession of men which is sufficient to provide a foundation for human solidarity. Genuine fellowship is grounded on a negative: it is grounded upon what men lack. Precisely when we recognize that we are sinners do we perceive that we are brothers. Our solidarity with men is alone adequately grounded, when with others [. . .] we stretch out beyond everything that we are and have, and behold the wholly problematical character of our human condition.[5]

Suzanne Collins leaves her readers in suspense until the end of Mockingjay, the third novel, before finally letting hope enter the narrative. We discover that Katniss and Peeta eventually marry each other, have children, and take up gardening. Maybe this is the inevitable end of the story, after Peeta’s episode of vulnerable honesty in the face of death at its beginning. Meanwhile, in our own story, we have already died a watery death and been raised with the one who entered our narrative as Hope. We know how the book will end. Believing that, may we be brave. May we be friends.

ALH: Amen. What she said.

[1] Suzanne Collins, The Hunger Games (New York, NY: Scholastic, 2008), 18 and 94.

[2] Ibid., 71, 113, and 141.

[3] See Amy Laura Hall, Conceiving Parenthood: American Protestantism and the Spirit of Reproduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008), 41.

[4] Kierkegaard, Works of Love, trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), 465; and Robinson, The Death of Adam: Essays on Modern Thought (New York, NY: Mariner Books, 2000), 255 and 259.

[5] Barth, The Epistle to the Romans (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1968), 100–101.