The whole south wall of my home seemed ready to collapse under a distressed drumming at the door one recent evening. While my wife went to the peephole I recollected some words from a sermon I’d heard years ago: “If our church catches on to the radical extent that Jesus calls us to love our neighbors, we’ll be the sort of community that has prostitutes banging down the doors.” When I first heard that challenge I don’t think I took it quite this literally.

I am part of a faith community called Awake Church, which has bound itself to a particular location along part of Seattle’s iconic Aurora Avenue. My church-planting pastor, Ben, had the seemingly simple idea when he began putting together our faith community that our mission would be to undertake Jesus’s command to “love your neighbor,” and we would do it in this particular place.

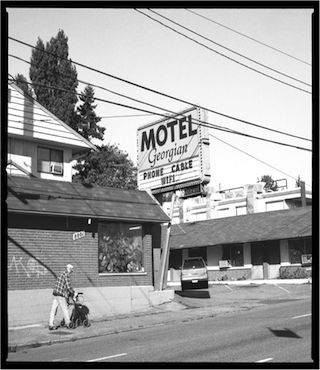

We could have picked a neighborhood where that’s a little easier. This secularized city is full of charming places that would benefit from the attention of some youthfully optimistic church folks. Yet we ended up in the neighborhood of Aurora, a neighborhood that is generally characterized by its less alluring attributes: seedy motels, vacant lots, various abused chemicals, sexual promiscuity, and the like. The land along this old highway is an eyesore, a blemish in Seattle’s otherwise clear complexion, and everyone seems to be sneering, “Can anything good come from Aurora?”[1]

But I have been digging, trying to unearth signs of Grace, and I have been discovering Jesus on Aurora in the same way that I have learned to recognize the incarnation in Flannery O’Connor’s fictional worlds. O’Connor was driven by an artistic impulse to discover moments of grace as penetrations in the darker parts of reality, and rather than blinding us with beautiful images of redemption—in which she resolutely believed—she challenged her readers to find life in places where it’s harder to see. Reading her work, I sometimes get the sense that she was putting God to the test by contending so boldly what others do blithely, that if the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ is somehow an animation of all reality, then in even the worst of our human predicaments we should be able to find signs of Grace. Aurora appears to be one of those darker places, and our church has been engaging in a provocation of O’Connor’s sort by pushing hard into that reality.

Jesus mingled with the socially demoralized, living alongside them in their present state of reality. The challenge of our work, which centers itself on that story of incarnation, is that we have to learn how to balance the neighborhood as it is with our hope for the way things one day will become. Our church community has found that committing to remain in this tension between those two ways of seeing the world is surprisingly radical. It deviates from the well-intentioned imperialist dreams of those who wish to drive out the “problems” in order to, as representatives of the city would say, “revitalize Aurora.” But one of the first things Ben clarified when he got this community in motion is that we are not out to impose our view of what a redeemed Aurora should look like, rather we’re attempting to discover that redemption together with our neighbors. Ben says we are searching for the marks of incarnation in Aurora under the assumption that, despite the general public’s perceptions, “a faithful and loving God is already at work. We simply wake up to what the Spirit is already doing.”[2]

This is what I mean by comparing our work to O’Connor’s storytelling. She reproaches novelists who “try to shake off the clutches of their region” in order to write a story with a more universal appeal. Her work was distinctively southern, and she claimed that such a careful attentiveness to place is the only way to write decent fiction. O’Connor says, “The discovery of being bound through the senses to a particular society and a particular history, to particular sounds and a particular idiom, is for the writer the beginning of a recognition that first puts his work into real human perspective.”[3] Her own work was an attempt to dig deep into her southern soil and then trust that stirring things up might somehow persuade Grace to emerge there, in the reality of her place.

* * *

The first time my wife and I decided to check out Awake Church, there was a gathering taking place on a Sunday evening in the backroom of a coffee shop called the Sweet Spot. We walked around the building to a narrow concrete stairway leading down to a door that one might have thought required a specific knock. I felt like we were persecuted Christians gathering in secret 100 years in the future or 1800 years in the past. Everyone had brought food to share, potluck style, and we wandered through the assembled crowd, until Ben called us all together.

“Welcome, Awake, he said—I noticed it was not, “Welcome to Awake”—“I just got word that one of the motels down the street has been condemned by the city for health code violations. It’s getting shut down and everyone who has been staying there is required to move out tonight. So right now, for our worship time, we’re going to take a walk over to give those folks a hand.”

The dozen or so of us headed up the street. When we arrived I was shocked to realize that these were more than seedy motel rooms; these were people’s homes. I met one elderly woman who had been living there for nearly twenty-five years. And there was very little we could do other than be present, which gave me an immediate taste of what it meant to be part of Awake, to be willing to hang around in the middle of social untidiness.

A few months after that first experience with Awake, my wife and I discovered an apartment for rent in a fourplex across the street from that still-condemned motel. We moved there because they would take our dog, and because it was fairly inexpensive. But it has felt like a rite of passage into a new way of being, like a comprehensive identification with Awake’s neighbor-loving mission. We could not have known then the profound impact that would come to us and our community from simply living day to day in that space, cultivating a place of hospitality, and allowing ourselves to be shaped by our neighborhood.

The apartment came with a large but miserably unloved backyard. But in a concrete jungle, the little patch of weeds had the rare potential to be a botanical haven. So the members of the Awake community started putting their imaginations together to consider how the yard might be put to use in a way that would cultivate our mission, that would allow us to, as O’Connor put it, “penetrate the surface of reality,” and to do it quite literally.[4] We started harrowing the soil and plucking out used IV needles, keys, condoms, and shards of broken glass. People from the neighborhood took notice of the work going on back there and began to join in on the effort, building garden boxes, relandscaping, planting, watering, and then watching the new life emerge. The outcome was a genuinely communal garden.

One Wednesday evening we had a celebratory cookout in the garden that attracted many of the people who were wandering by and helped us discover that the people in our church community weren’t the only ones looking for ways to connect with neighbors. And so we began hosting the cookouts more frequently, and they have now become a regular Wednesday evening occurrence during the summer months, a weekly time of connecting. I have been amazed at the way people from every walk of life are so happily willing to wander across social barriers into these momentary experiences of an alternative reality.

There used to be a coffee shop next door to our garden that was named A Better Buzz (a nod to the local Alcoholics Anonymous fellowship). The coffee shop went out of business a couple of years ago and our church has taken over the lease. Over the past year, we all worked together to do a large-scale remodeling project, turning the space into something that I like to describe as a neighborhood living room. We have named it the Aurora Commons. The Commons provides the safety of hospitality so that our neighborly interactions can flourish. It feels to me like an extension of the garden’s mystery, only with a roof to enable year-round access to mystery.

* * *

Ben found out not long after naming our church “Awake” that in Latin, Aurora means “dawn.” The Psalmist says, “My heart is steadfast, O God, my heart is steadfast! [. . .] I will awake the dawn!” (Psalm 57:7–8, NRSV). Our church began with the intention to love our neighbors and we are right now living in the middle of that story, trying to be attentive to the moments of Grace as they emerge. We have few presumptions for what that should look like, and we’re uncertain of what it will become, but the act of binding ourselves to unlovable Aurora has enabled us to see further into the great reach of the Incarnation.

And I’ve started to wonder if these moments of Grace are becoming easier for us to see because we are now more connected to the stories that redemption comes wrapped up in. I’m thinking, for instance, of my neighbor Denny who sleeps in an old conversion van on my street. A year ago Denny was nearly suicidal in his depression. He and I have spent a great deal of time working through this together, but no matter how hard Denny tried, he could not escape the world he was living in twenty years ago, when he was a drummer in a grunge rock band. Our church has struggled deeply with him, too, and on his behalf tried to imagine what something like redemption might look like for him now. It has seemed always to no good end, and I have quite often found myself on the edge of giving up hope for him.

That is really the question of all our work. How do we imagine redemption? And how do we set aside our preconceptions in order to see what it will look like? The appearance of redemption is God’s to determine, and if we try to initiate it without a story, without a sense of place, we may be making a frightfully imperialist advancement. It seems to me the best we can do is keep on digging and overturning soil until some sign of Grace finally emerges within our field of view.

It is enough that the other night, I saw Denny camped out next to a bonfire in the garden because, he said, “I felt like lying under the stars.”

* * *

O’Connor says, “The novel that fails is a novel in which there is no sense of place.” In response to a handful of manuscripts she reviewed, she criticized the language and characters because they seemed like they had emerged out of a television. Despite the fact that these writers all lived in the South, O’Connor said, “[Their characters] might have originated in some synthetic place that could have been anywhere or nowhere.” I think you can easily read “church communities” in place of “short stories” in her grievance about writers who do not root their work in a particular place: “They want to write about problems, not people; or about abstract issues, not concrete situations.” She says, “They don’t have a story and they wouldn’t be willing to write it if they did.”[5]

A lot of people write stories with the idea of achieving some kind of universal appeal. It’s no different with music, film, and poetry. And I think most of us know this happens with churches as well. Too often O’Connor’s line is a fitting description for these churches: they could be located “anywhere or nowhere.” And I think it is important to recognize the sentiments behind the seamless and captivating but utterly generic programs of such universally appealing churches. The disjointed but collaborative composition that makes up our neighborhood faith community’s ecclesia is different because it is an unearthing of Grace that is bound up in the sense of place.

Awake gathers together in the Commons somewhat dependably every Sunday now. Denny has been playing a drum lately, which I don’t think any of us could have imagined a year ago, and adding his voice to mine, and to my neighbors, and to the socially demoralized, and to the youthfully optimistic, as we together worship a God who breaks into all the corners of reality.

Main page photo courtesy of Joshua Longbrake.

[1] See John 1:46.

[2] Ben Katt, “Aurora Part III,” Awake the Dawn, September 28, 2007, http://awakeseattle.blogspot.com/2007_09_01_archive.html.

[3] O’Connor, Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, ed. Robert and Sally Fitzgerald (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1969), 198.

[4] Ibid., 168

[5] Ibid., 199, 56, and 90