Sooner or later, every fighter learns the importance of respecting one’s opponent. In many cases, this lesson is learned on day one. You walk into a gym with shiny new boxing gloves and an unhealthy dose of self-confidence; you walk out with a shiner over your left eye and a newfound respect for other peoples’ skills.

It doesn’t happen overnight, of course, but little by little, some fighters learn not only to respect their opponents’ skills but also to respect their opponents themselves—to admire the persistence of an opponent who has submitted himself to the daily discipline of training and dieting, to admire the patience of an opponent who has worked for months to improve one single technique, to admire the courage of an opponent who has stood across the ring, accepting the likelihood of injury and the possibility of defeat.

It may strike some people as ridiculous to suggest that two people whose sole aim is to render each other unconscious through concussive blows do, in fact, respect one another. And yet, the sport of mixed martial arts is saturated with respect. How else are we to explain the fact that so many professional fights end in a long, sincere—even intimate—embrace? American men don’t hug men that they don’t respect.

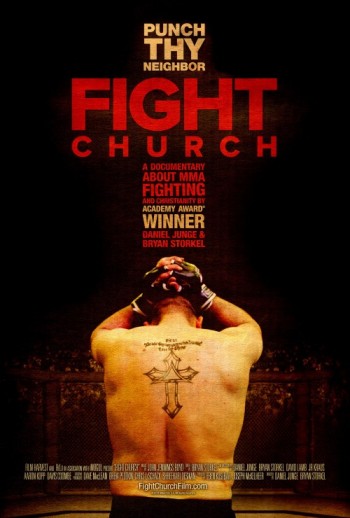

And since the sport of professional fighting is capable of teaching its practitioners how to respect one another, we should not be surprised to see that a documentary on the topic does the same. Fight Church is a disciplined, sympathetic look into the lives of Christian fighters. Never devolving into spectacle or allowing implicit criticism of the sport to lapse into caricatures or cheap shots, the filmmakers have succeeded greatly in preserving the humanity of their subjects. This is no small achievement, considering that most criticism of the sport relies on a depiction of fighters as Neanderthals, and most promotion of the sport relies on a depiction of fighters as demigods.

The Pugilistic Pastors of Fight Church

Fight Church follows the paths of three Protestant pastors who moonlight as mixed martial arts fighters (aka cage fighters). And yet, moonlighting is not quite an accurate description of what these men do. After all, they are amateurs, so they receive no payment for their fights; they train and hold classes during daytime hours; and they recognize no separation between their work as pastors and their work as fighters. If the men of Fight Club, that popular novel-turned-Hollywood-blockbuster, were office rats for whom fighting served as a break from—and rebellion against—the banality of their white-collar existence, then the pastors of Fight Church are quite the opposite: men for whom there is no distance between the workday and weekend fights.

Indeed, to hear the men tell it, they are fighters exactly because they are Christian pastors: “My training is worship. The way I compete is worship,” says Preston Hocker, who fights under the nickname The Pastor of Disaster. “Everything I do,” he says, “I do it as if it is worship to God.” Pastor Joe Burress says much the same about his fight ministry: “Everything we do is about God. Faith is saturated in what we do.”

I take it as a general rule of polite discourse that when a man tells you something about himself, you ought to believe him. Don’t attempt to uncover hidden motives, and certainly don’t accuse him of lying. Accept what he says in humility and trust, for this is the foundation of dialogue. Very well then. A shin-kick to the face that shatters an opponent’s orbital and leaves him concussed or a heel hook that intentionally tears an opponent’s ACL and requires surgical reattachment—these are, according to the pastors, fragrant offerings of worship; they ascend to God on soft billows of smoke, and with these humble gestures, the Prince of Peace is well-pleased.

“But surely,” these men might object, “We don’t want anybody to get hurt!” (I suppose this is another rule of polite discourse: When speaking or writing about someone, it is good to anticipate and give voice to their responses if they are not present to do so themselves.) And indeed, there is a sense in which the pastors truly do not want anybody to get hurt. Throughout the film, they are shown praying to God, asking for divine protection against injury before practice and competition. The men pray this not only for themselves but also on behalf of their competitors.

This raises an interesting question: What does it mean that Pastor Paul Burress has suffered at least ten serious concussions in his career? I mean, aside from the likelihood that he will be soiling himself before he reaches retirement age, what does it mean? Does it mean that God has chosen to ignore Pastor Paul’s pleas for protection? Should we regard him as among those objects of wrath that the potter has prepared, in advance, for destruction? Have the pastor’s intercessory prayers finally fallen on deaf ears because he is counted among the reprobate?

Or rather, is the explanation slightly less theoretical than that? Might it simply be the case that people who fight in cages get concussions? That prayers for protection are supremely foolish if a person is going to willfully engage in violent behavior? When the Christian martial artist calls out to God for protection in battle, he does so in vain. The same can be said of the ISIS jihadist, the member of the Israeli Defense Force, and the US soldier who clutches his rosary or cross. There are some miracles that God cannot do.

No less sincere than their prayers for protection are the pastors’ prayers for victory. “Dear God, thank you for the win!” exclaims Pastor Paul, during a prayer with one of his victorious parishioner-fighters. Likewise, Pastor Nashon Nicks cries out to God before his fight, “Lord give me strength.”

These prayers for victory are reminiscent of a scene in Mark Twain’s brilliant short story “The War Prayer” in which “the pastors . . . invoke the God of Battles, beseeching His aid in our good cause in outpourings of fervid eloquence.” And just as the stranger in Twain’s story reminds the churches that their prayer for victory in battle is really two prayers—one “beseeching a blessing upon yourself” and one “invoking a curse upon your neighbor at the same time”—so too, does a US kickboxing champion named Scott Sullivan remind us what Pastor Paul’s prayer really means.[1]

“The object of this sport is to damage someone. It’s the goal of the game,” Sullivan states with rare and refreshing honesty. And it is this inescapable feature of professional fighting that ultimately prompts Sullivan to quit. Despite all of the very good things that can be said about mixed martial arts—the sport’s ability to instill discipline through focused practice and dieting; its tendency to teach athletes how to work for the common good by bringing them together into teams; the way that competitors learn the value of persistence in training, delayed gratification in victory, and humility in defeat—despite all these positive attributes, it is finally the inherent violence that causes Sullivan to give it up.

And yet, as we shall see, it is precisely the violence in mixed martial arts that draws many men to the sport.

The Pernicious Parents of Fight Church

If a grown man were to strike his young son in the face—drawing blood, bruising the boy’s eye, and causing significant emotional distress in the process—that man would probably be arrested. Most reasonable people would say that the child should be protected from the man.

And yet, when a grown man raises his young son to participate in youth kickboxing matches—to be struck in the face, to have his eye swollen shut, to risk broken nose and concussion, to be placed in the middle of a ring to punch and kick another ten-year-old boy while hundreds of adults watch and cheer—that man is called a good father.

Why? What makes us call one dad abusive and the other honorable? What makes adults want to intervene on behalf of one young boy, while many of those same adults scream for the blood of another young boy?

Clearly there is something very big at stake here. There must be some important reason that a man named Kelly enters his twelve-year-old son, Lucas, in youth kickboxing matches. “[Lucas] has had a fight, and he took a pretty good beating,” Kelly states, before assuring the camera: “It won’t happen again.”

But it does. Lucas is mauled by a smaller, younger opponent. And his father must have some compelling explanation for watching his son from a distance—muttering under his breath and scowling, as the boy takes another pretty good beating. Likewise, the increasing number of adults who enroll their children—some as young as five—to fight in steel cages must have a very good reason to do so.[2]

And that reason, articulated most clearly by Pastor John Renken, is to make a certain type of man. Renken states that,

Mainstream Christianity has feminized men. We’ve taken away their God-given attributes of aggressiveness and competitiveness. We expect men to be prim and proper, and polite all the time. You never respond with aggression and with force. . . . To act like females. . . . The vast majority of problems we’re having in our culture today are because we don’t have a warrior ethos. We have a bunch of cowards. A warrior ethos, if properly developed, will do nothing but help our society. . . . If we raise our boys to be men of honor and integrity and strength who will stand up to evil, and wickedness, and unrighteousness—these kind of problems will go away.

Renken does not elaborate on the societal problems that he believes will be solved by the cultivation of a “warrior ethos.” Neither is it obvious what “evil” he is referring to or how that evil will be overcome by male aggression. But one thing is clear: Renken has an enemy in mind.

So does Joe Burress, father of Pastor/Fighter Paul Burress:

Some Christians have this attitude that we’re floating down in a canoe on a gentle river, drinking a Pepsi. That’s not [correct]. Jesus said, “Upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell will not prevail against it”—which means we need to charge them, not wait for them to come to us.

Who is this enemy? This imminent threat? This coordinated, sinister, rapidly advancing them?

That’s a trick question, of course; there is no them. Or rather, there is no singular description that might be useful in helping to identify them. Them is everywhere; them is anybody—anybody who is not us. In the mind of the American man, there are innumerable, constantly changing, ever-present enemies. There is always somebody to fight. And so, we must train our sons to fight in cages; we must raise our boys—as Renken is shown doing—to shoot handguns; we must create a “warrior ethos.” Put down your paddles and soft drinks, pansies; life is war. And this is all there will ever be; it is the fundamental order of things—thus Renken’s insistence that male aggression is “God-given.” The men who do not share this vision of masculine dominance have obviously been deceived and taught to “act like females.” Be sober and watchful men, for your enemy prowls around like a lion, tempting you to sit while peeing.

And though men are not to “act like females”—what about those females that act like men? In other words, what about all the girls and women who fight in cages? Female fighters are shown throughout the film, and Pastor Paul even trains some of them. Doesn’t the presence of these women complicate the pastors’ silly and simplistic account of gender?

In one of the final scenes of the movie, two Christians are shown fighting each other in a cage. And as Pastor Nashon Nicks squares off against Pastor Preston Hocker, the failure of Christian masculinity is—like a lamp on a stand or a city on a hill—placed on full display for all to see. “Hopefully God isn’t with him tonight,” Nicks says before the fight.

Don’t worry, pastor—She’s not.

[1] Twain, “The War Prayer,” in Europe and Elsewhere, http://warprayer.org/.

[2] See James Nye, “Inside the Outrageous World of Child Cage Fighting: Tiny Boys Who Are Trained to Attack Each Other in America’s Baby MMA Arenas,” Mail Online, November 4, 2013, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2487527/Inside-world-child-cage-fighting-Boys-trained-attack-MMA-arenas.html.