Dominique Ovalle is a Californian artist whose work sparks with luscious texture and color and a search for absolute purity of form. She primarily works with oil on canvas, but she also experiments with found objects and larger outdoor murals. Her paintings have been featured in several group and solo exhibitions and were recently featured on the cover of Claremont Journal of Religion. In this interview, Ovalle shares how the collaborative outdoors, the solitary studio, roadkill, and the cockroaches of Palau have all influenced her work.

The Other Journal (TOJ): Before we dive into the philosophical depths of your work, could you tell us a little about yourself?

Dominique Ovalle (DO): I was a kid in the San Francisco Bay Area, a teenager in Fresno, and an adult in Malibu, where I attended Pepperdine. I was an art major, but after graduation, I continued to study art history in Fresno. I got my chops at Pepperdine—painting all of the time and starting an art club on campus. And while in Fresno, I threw together pop-up shows and painted murals with a gang of wild boys from the Wild West of Downtown Fresno. Wild boys and girls I should say. There were few, but they were proud.

TOJ: And what are pop-up shows?

DO: For us, pop-up shows meant making a bunch of new work and then finding our own venues or places that could function as galleries. Fresno was a great place to start working post-undergrad because although there are a few links here and there to the surrounding art world, it is under the radar and largely invisible from the LA art scene. The mural scene is out of control in Fresno. They have no mural codes—yet. The city has been talking about instituting them, but I hope they never do, except to protect the murals. Basically, if you can get your sketch approved by the building owner—and most of the time you can, because no one cares about property in downtown Fresno—the wall is yours!

TOJ: That’s so rare. It sounds like a win-win situation for both the city and the artists. The work we tend to feature in the journal is completely different from mural work. Murals seem to become a part of the architecture upon which they are placed, inherently sharing their narratives and living within communities.

DO: Murals are about storytelling. I believe they can be very powerful when the artist is aware of where they are painting and what message they are sending to the people. But the architecture is where I find a limitation with murals. Successful murals evoke an essence, and when you are painting where signage goes that can be hard. Yet, sometimes the place morphs to fit the mural. Here’s what happens when murals go wrong: http://abclocal.go.com/kfsn/story?section=news/local&id=7081547.1

TOJ: How would you compare mural painting to the painting that you do in the studio??

DO: The two are very different. Painting in the studio is intimate, whereas mural painting is more of a public performance; it is you against the elements. A larger studio work can be mural-like, especially in the physical making of the piece—the body movement, the elevation you experience while on the ladder—but I think my mural aesthetics tend to be more illustrative. When I paint a mural, I am painting with the public in mind; I really try to consider who I am painting for when I am outside on a wall, whereas in the studio I can be much more personally expressive.

It is also faster and easier to paint indoors. It’s easier to stick an object onto a panel than onto a rough or crumbly wall. It is so much more contained. The studio, for me, is a place where I have ultimate control over nature, a place where I shut out the elements and, as an unintended byproduct of being indoors, the sublime. I can be more expressive of my interpretation of the world there, but I can also drift farther away from the essence I am trying to channel. With my landscapes, for example, I am constantly trying to reimagine what I felt and saw when I was in a particular locale.

Drawing from my surroundings is actually very important to me, and I’ve found that my work changes with each travel experience. I did a crucifix painting after a summer in India. Cloth, mixed media, and tactile surfaces became a huge part of what I was doing then. And color! Color! The crucifix painting even includes a real rattlesnake head under the cross. I got it from some Fresno roadkill when I was living at home with my parents and riding my bike everywhere.

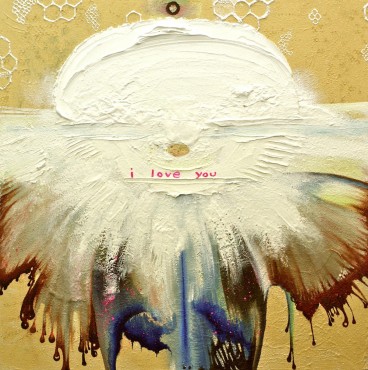

And speaking of surroundings, I created the painting Daddy God on the cover after feeling really connected to God. It was closer to the period of time when I was doing more illustrative work, so I think there is a large dose of that explicative style in there with the text.

TOJ: It’s unfortunate that we can’t view these pieces in person because the texture and found objects in your work seems particularly important. And roadkill! You don’t see that everyday in a painting.

DO [laughs]: Don’t worry! It’s sealed in plastic medium. That is an example of my artistic, illustrative rigidity. It is literally the crucifix crushing the snake—a literal symbol.? though, because I actually really like snakes in real life.

TOJ: You said that you are continually trying to grasp and reimagine the experience and feel of a place. To me, that sounds similar to a meditative practice. Can you say more about that?

DO: The landscapes I create are really about transportation. They are about transporting the mind to see a place again. They are partly an escape, but it is an escape to a place that exists nowhere—only in that painting before you.

TOJ: How does transportation function in your non-landscape paintings then? Or do you consider all of your work to be a type of landscape?

DO: I guess I see the others as three-C paintings: they’re confrontational, conversational, and confessional. These paintings are usually centered, and somewhat protruding, with a main focal point that’s smack-dab in the middle—confrontational. They’re conversational in that each mark is a conversation with the other marks. This way of painting was a gift from my dear fathers, the Ab Ex painters.2 They are also conversational, of course, because while I’m painting, I know in the back of my mind that someone will look at this later and enter into the visual dialogue. Images are powerful things, and these images might be remembered by someone.? These paintings are a continuing conversation; they leave me and go out into people’s memory? And they are confessional, because the works are deeply personal; they are from my heart and soul.

TOJ: Are there things that you aspire to in terms of how people might remember your paintings?

DO: People make movies, music, paintings, cartoons, comics—every kind of art—and all artists have the chance to create an image that will enter into the memory bank of their viewers. I have no idea what people think of when they see my work, but yes, I hope they remember peace. At the risk of sounding like a fool, I hope they remember beauty.

TOJ: Why a fool? You seem a little unsure about mentioning beauty here.

DO: There is a tendency for some people to sneer at beauty or to revile it, because it is so attractive and magnetic. That makes it untrustworthy to fearful people. If people have been let down before—by life or the actions of others—there may be a tendency to mistrust things that appear to be good. It is hard to swallow that some things are good, beautiful, and true. Hans Urs von Balthasar said, “We can be sure that whoever sneers at [beauty’s] name as if she were the ornament of a bourgeois past—whether he admits it or not—can no longer pray and soon will no longer be able to love.”3 When people do encounter something pure and beautiful, they have an opportunity to accept it, to believe it. That is the pivotal moment: when art meets life, when it meets reality, when it meets you and me. That’s where the conversation is.

TOJ: I am sometimes guilty of being skeptical—sneering sounds easie?st sometimes. This reminds me of Oscar Wilde’s “The Critic as Artist.” For a moment, toward the end of the essay, he talks about how art can draw emotion from viewers without then turning on viewers. It can draw out and reveal beauty without turning around and disappointing. And it can also be an object that allows for grief undisturbed.4

DO: I am also guilty of being skeptical. That is where we must become like children. A colleague taught me that entering a?n art show is like seeing the opening act of a play or the first moments of a film: in those first seconds you either believe it or you don’t. That Oscar Wilde paraphrase just sucked the breath out of me—grief undisturbed, like crying in front of a Monet and hoping no one sees.

TOJ: Exactly. The painting, artwork, or object won’t shame you for crying. Or for laughing. It lets you experience everything.

DO: Yes, why do we feel shame for crying? Is that because we are American? Or because we are feminists?

TOJ [laughing]: Going back to the von Balthasar quote you mentioned, it seems that experiencing beauty should lead to action, the action to love.

DO: I like the quote because it defends beauty as an attribute of God—not as an excess but as something pure, true, and good. The action to love is beautiful. I love to make things beautiful and colorfully harmonious, and when I am finished, I think it’s important that I accept that beauty and not be ashamed of it. That’s what I strive for.

TOJ: Does this translate into qualities you search for in your painting as well? In having said that you hope viewer’s will remember something of beauty from the work, I am curious whether you also hope also that your work will inspire action.

DO: Oh, taking it up a notch! Yes, if it inspires love, or a lovely action, that would be awesome.

?TOJ: When I look at your landscapes, I see the potential for these pieces to function like contemporary icons. Is that too far of a leap as far as actions might go? I say icon because of your earlier description of the meditative quality in making the work, and so I wonder whether you see them also functioning as something a viewer might pray or meditate through, as one would pray or meditate through an icon in certain spiritualities.

DO: I suppose my paintings act as a stand-in for the human body. We look at a painting and see our presence in nature, deleted of our body, and our mind leaves the body and enters into the landscape. So, yes, I can see them being icons—as signifiers and symbols. The canvas is an artificial scenario trying to describe an experienced truth. Like a body thigh. I suppose they can also function more precisely as a prayer icon of sorts, if the viewer wants to use them that way, but I see them mainly as a relief from reality. It depends how people use prayer. I don’t think prayer is a relief from reality; I have always thought of meditation as going inward, searching for something. But I do see these paintings as a place for the searching.

TOJ: We have covered a good bit of territory. Is there anything we haven’t talked about that you would like to mention?

DO: When I was traveling in Palau last summer, I stayed at a home, and on the guest bed was an ugly, plaid country-kitchen-style pillow with the words Romantic Life embroidered on the surface. The pillow was dirty and worn. I just loved that. Seeing Romantic Life in a dirty bed in Palau with cockroaches crawling in the closet beside me, the air hotter than Brazilian balls, the humidity suffocating me—it was a rich experience yet very different from the “exotic” crown jewel of sunset vacations that was advertised in magazines.? That’s a bit like the artist’s life. It’s dirty. We may starve, but we chose this, and in the choosing, we were really chosen. Becoming artists was just our unavoidable response. That’s what I am thinking about these days—the artist’s romantic life.

TOJ: So true. Unless you are Damien Hirst.

DO [laughs]: Something tells me he isn’t Don Juan with all of that rotting shark juice. But I can’t really talk—I’ve used dead animal parts in my art too.

TOJ: There are many misperceptions about the gritty life that is a reality for the majority of artists working today. That memory from Palau is a great metaphor.

DO: Yes, the daily lives of artists are like the daily lives of the people of Palau, and the false image of the island is bought and sold in a thousand vacation magazines.

TOJ: Well, we started with roadkill, so why not end on cockroaches? One last question before we do. Do you have any exhibitions coming up?

DO: I have a few opportunities in the future, perhaps, but I’ve mainly been concentrating on my thesis show, which was held at the Peggy Phelps Gallery.

1. “Controversial Mural Still Standing in the Tower District,” ABC, KFSN-TV/DT Fresno, CA, http://abclocal.go.com/kfsn/story?section=news/local&id=7081547.

2. See Paul Stella, “Abstract Expressionism,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/abex/hd_abex.htm.

3. Von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics, vol. 1, Seeing the Form, trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis, ed. John Riches (Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 1982), 18.

4. See Wilde, “The Critic as Artist,” in Intentions (New York, NY: Bretano’s, 1905).