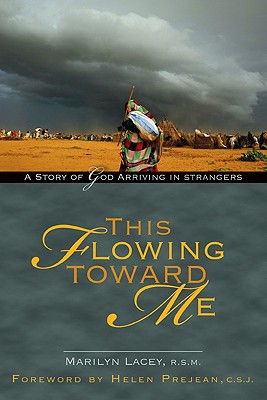

In the complex politics of the world market, borders frequently shift and governments often fail. Millions of people become refugees. And these people are left to suffer at the margins, homeless and powerless. Since becoming a Sister of Mercy in 1966, Sister Marilyn Lacey has emerged as an important advocate for compassion toward people who are displaced and seeking refuge around the world, particularly through her work with Mercy Beyond Borders. The Dalai Lama has even described her as an “Unsung Hero of Compassion.” In this interview, Sister Lacey discusses her new memoir, This Flowing Toward Me: A Story of God Arriving in Strangers, her fear of spiders, her work with refugees, and her surprising encounters with God’s grace.

The Other Journal (TOJ): Thank you for speaking with us. What motivated you to write This Flowing Toward Me? And why now? Are there any factors in contemporary American culture that were your motivation?1

Sister Marilyn Lacey (ML): For twenty-five years or more I’ve been telling anecdotes to friends of the things I’ve experienced with the refugees. And they say, “Oh! You really should write that story!” But I’ve never had time. Then after 9/11, when the United States became so fearful of outsiders and every foreigner was seen as a potential terrorist instead of a potential blessing, I thought that it was time to really get serious and write this.

My experience has been that interacting with strangers is the window unto God, the God who is Other. It’s my genuine experience; it’s not some theory or theology that I’m writing about. It’s my day-to-day experience, and most Americans don’t have those opportunities. We’re so insular here in the Untied States. So I thought that if I share these stories, maybe it will change people’s hearts and open them up a little bit to the refugees and migrants who are already in our midst and to those who are not yet here in the States but who are overseas. We’re all brothers and sisters. I feel it in my gut. I thought through simple stories that are not scary people would open up to that.

TOJ: It reminds me of an interview we did earlier with Sister Helen Prejean regarding her work with inmates. She spoke about working with the stranger on death row.2

ML: Exactly, that is why I asked her to do the introduction to my book, because she’s had the same experiences.

TOJ: What are you feelings about the current resurgence of interest in social justice? Is there anything you want to share to those who come after you?

ML: I’m very hopeful about the upcoming generation. When I was young we were not thinking globally in the way that people today are—that’s another reason I wrote the book. Everybody speaks of globalization, our shrinking planet, and all of that, but we still are divided by tribalism. And I don’t just mean tribalism in Africa, but a tribalism that is nationalism, that pits one country against another; there is tribalism in our economic systems that have people on top and people on the bottom. We need to get beyond all those kinds of divisions. We see it happening in the environmental movement; we see it happening in the human rights movement; we see it happening in the women’s movement. Now with President Obama in the White House, I hope we start to understand that race is not an issue worth division. There is a lot of hope out there. After working for so long with refugees, I believe we have to evolve to the point where war is not the answer.

And it’s not just a human tragedy, its also an environmental tragedy; war is disastrous for ecosystems. The refugees end up clustered in tens of thousands in places where there were never meant to be such large concentrations of human beings. They dry up the water, they cut down the forests, and they do all kinds of things that are really harmful to the environment. It’s not the refugees’ fault—they need to survive. It’s the upheaval and displacement that come from war. We have got to evolve. My grandmother always said, “We should put only grandmothers in charge of countries because they would sit down, have a cup of coffee, and figure out how to work out their differences. They would never send their grandsons to war.”

TOJ: And they would joyously give you two helpings too many at the dinner table.

ML: That’s right. Everyone would go away happy.

TOJ: In your book, you speak of the tensions that can arise between host countries and refugee camps, some of which have people who stay there a decade or more. Has experiencing these tensions overseas informed your view of tensions between people groups here in America? Are there ways that other countries address these tensions, well or otherwise, that inform your view of race here?

ML: I still think that the United States is further ahead than other countries in getting race relations right. I suppose there are some countries that are much better than we are, but in general, we have allowed economic and social opportunity for folks no matter their background. That is the key to harmony. Blending different backgrounds makes a culture grow stronger. That’s the genius of America. It obviously doesn’t always work—you’ve got slavery and disadvantaged groups—but it works better than in most places. So you see in the Balkans, the problem after Yugoslavia collapsed: Tito was gone and communism had kind of kept things under control, but then it all exploded. The Serbs and the Bosnians were at each others’ throats. So this is not an African problem. People are always pointing at Africa and saying that they should just get over their tribalism, but look at Afghanistan: it is riven by long standing tribalism. I think tribalism is one of the big problems we face even though we are an era of globalization.

The more things become the same around the globe, the more people feel this need to be on top—my tribe, my race, my ethnic group. It’s so ridiculous. It’s ego driven and power hungry and stupid. In the refugee camps, it’s not always, or even often, about race. It’s usually about power and control. Refugees are forced out of one country and then are clustered along the borders of another country. It’s a dangerous buffer zone. The rebels and fighting groups from the war-torn country still make incursions there to recruit teenagers and cause trouble. For example, between Sudan and Kenya or between Sudan and Uganda, where the camps are, nobody wants refugee camps in their territory. It’s unsteady, unstable, and dangerous. The United States is no exception to that—we didn’t want refugee camps here, and so we pushed back the Haitians. We push back migrants all the time, even though it’s against international law. The solution is not better programs in the refugee camps. The solution is to learn how to have political settlements rather than military solutions.

TOJ: I’m originally from the Midwest and as I read about your work, I find myself wondering where to start. How could someone that can’t travel internationally begin to serve the refugee population?

ML: Great question. A person can always start right where they are by simply working to become more welcoming of strangers. Smile at the person in front of you at the grocery line. Open up a little bit to conversation. Make links and friendships with somebody that’s not in your circle. You might meet this person at the grocery store, the church, or the street corner. Don’t be so fearful of people you don’t know. We’ve lost that sense of community in America. The refugees often say that the streets are empty of people and no one talks to them. We, as Americans, are very private, individualized, self-sufficient, and insular. So first, you can start wherever you are just doing that.

Then in most American cities now there are migrants. The Midwest is a great example. There is a huge influx of Spanish-speaking people moving into the Midwestern meatpacking plants, factory jobs, and farm labor. That’s been a very rapid transition over the last ten to fifteen years. Again, these migrants tend to cluster on the other side of town and don’t have much interaction with others. But there are ways that people can reach out and make those connections. Usually a group setting is less threatening. For example, a church can invite another church from the other side of town to have a picnic together. It’s real practical stuff.

There are also refugee resettlement agencies in many of the major towns throughout the United States. The U.S. government subcontracts with nine different agencies to welcome official refugees at the airport. Someone goes into the refugee camps, interviews them, and then puts them in an airplane. When they land in the United States, these agencies pick them up at the airport, teach them English, and get them jobs and housing. In most major cities, there is at least one major office of one of those agencies. In some major cities, all nine agencies are present—for example, Catholic Charities, International Rescue Committee, and Jewish Family Services.3 If anyone really wants to become a “welcomer” of these marginalized people, call these agencies and ask what kind of volunteers they need. They’re always looking for volunteers just to befriend the newcomer.

The refugees come to America, see everyone racing around, and ask me how they can make friends here. A lot of these agencies will hook a new arrival up with a volunteer who will simply befriend them. Once or twice a month they will meet up and go out to the park and talk. Or they will go to the grocery store and walk through how to do comparison shopping. Everything is wrapped up in plastic—how are they supposed to know what kind of food it is, unless someone helps them? Simple things. Tutor them in English. Help the kids with their homework. There are many, many ways to get involved. You can write a check. Getting personally involved is very transformative for the volunteers. I strongly believe, as I put in my book, that anyone who welcomes these strangers is meeting God. I was with Catholic Charities in San Jose, California, for a couple of decades welcoming refugees from all over the world, and we had fabulous volunteers, ordinary people doing ordinary stuff. They would come and thank me for letting them be a volunteer. I would tell them that it should be the other way around, I should be thanking them. They would say, “No, this has been the most graced experience of my life!” For example, when you are working with a refugee woman from West Africa who has lost her husband and her children and has lived in the bush for ten years having survived all kinds of trauma, she comes to America and she is so grateful even for a loaf of bread. This changes the way you look at life. It’s grace. It really is. Ordinary people anywhere in the United States can get involved welcoming strangers near and far. Most cities you can get involved in the real work of welcoming refugees.

TOJ: I would imagine that most people, like myself, feel a little overwhelmed or afraid or unprepared.

ML: Exactly, that’s why I suggested that the first thing to do is to do it through a group. Get together with your book club or your church. You might need to get together with a couple of friends before you jump into something like this. People get nervous and wonder what they’ve gotten themselves into. This is another reason that I wrote the book. I started out that way. I started out as a volunteer at the San Francisco airport. I saw a note that was asking for volunteers and I thought, “Hm. This is weird. I have never seen a refugee; let’s go find out what it’s all about.” It turned out to be such a blessing for my life. You do have to take a little risk outside of your comfort zone, but you don’t have to do it alone.

TOJ: Did you experience difficulties or doubts when you began this work? Do you experience these now? What do you do with them?

ML: I slog through it. The worst part for me was the spiders when I was working in the camps. I don’t want to say that this is a piece of cake. The experience of the refugees is horrific. If you become close to them and you share that kind of pain, it’s not all fun and games, but it is still a blessing. It’s hard to explain. God is close to the broken-hearted and when you stand close to those folks, you’re somehow graced. I know this could sound “pie-in-the-sky,” but it’s not. These people that have volunteered and been changed were not all believers in any sense, or Christian, but still after this work, their lives were opened to a bigger mystery. I have a wonderful volunteer, a woman who is dying of cancer, and she says that the refugees have been the most remarkable blessing for her. She is not a believer, she doesn’t believe in God at all, but she says, “Put it into perspective. Yeah, I’m losing my hair. I’m losing my ability. I’ve lost my job. But I haven’t lost what these refugees have lost, and I can help them rebuild.” And so she is. Talk about inspiring. It’s amazing.

TOJ: One thing I thought was interesting in your book was that as your love increased toward the people you were encountering, your love for all sorts of things increased as well. For example, you told of reading a poem you found by Rumi and weeping. Your heart had become more tender toward all things.

ML: All I can say is that this work cracks you open to life. We can insulate ourselves from life with all our possessions and busyness and our successes. We end up sitting on top of the pile, but with this work, a conversion happens. You get really close to people that have suffered. It’s not like you just sit with them and weep; you help them rebuild and there’s a wonderful gratitude that grows in you from that.

TOJ: I’d imagine that there is a lot of joy among the refugees. Unfortunately, I sometimes get the idea that it is perpetual suffering for them once they get to America, and I don’t think that’s true.

ML: Yes. That’s a very good insight and it’s true. Their troubles are not over when they get to America, but at least they know they’re climbing out of the mess that they’ve been in. With hard work, their children’s lives will probably be better than theirs were. They’re filled with hope when they come here. The smallest things that we take for granted can be wondrous to them. Of course, it’s the cream of the crop that gets here. The weak ones die or don’t make it out of the camps. So we’re dealing with an infusion of energy for the country from the refugee folks. Though not all of them. Some of them come very broken. There are some that never get over the trauma, whether psychologically or otherwise. That’s maybe 5 percent.

TOJ: What are you working on right now? What’s been your passion lately?

ML: I have this organization called Mercy Beyond Borders. That’s where I am spending a lot of my time right now. I am doing a lot of public speaking around the United States, raising money, and going back to Sudan twice a year to make sure that our projects are up and running and getting the right people in place. It’s my full-time work and I love it. I feel really happy to be involved in it.

TOJ: I really enjoyed how you told about this heavy topic in your book. It was like sitting in a rocking chair listening to stories. I am wondering how are you doing with spiders?

ML: You know when I first talked to my publisher he told me that it was a little too long and he wanted to take out the chapter on the spiders and the chapter on the food. I said, “Don’t you dare! That’s the human side of it. That’s the light-hearted side. If you take that out, nobody’s going to read the book; it’s just too heavy.”

Life is full of ups and downs. I am still terrified of spiders. I found one in my room last night and let out a karate yell and had a rush of adrenaline. I’m just terrified of them. But you move on and try to see what you can learn from every experience.

TOJ: That’s another thing that I loved about the book. I felt that you noticed the things I would have noticed. Sometimes when I read books about justice, I feel like I’m too human for what I’m reading, because I wonder about the food, the insects, and all those other things that come with visiting a new place.

ML: I’m a strong supporter of social justice stuff, but sometimes you read that genre and people sound angry. It gets all heavy, and justice starts to feel like a should, and to me work for social justice should be something you’re drawn to, pulled rather than pushed—pulled in by a God who wants the world to be different. So I wanted the book to feel inviting to people and not like a burden, not like “Everybody ought to go do something for refugees!” No. Instead, here’s a story of the joy that I experienced that could be yours if you would take a little risk. That’s how I hope the tone of the book is. It should be light and inviting, even though the stories are searing.

TOJ: That is exactly how it felt. It felt like you were showing us a joy that we have yet to discover.

ML: That’s exactly what I hoped for. God wants us to be joyful and to spread that around. I think too often religion is about oppressing people, keeping them in line and controlling them. God is not like that at all. We have got to evolve a little bit.

TOJ: Could you explain the title of your book, This Flowing Toward Me? What did you mean by that?

ML: It’s from a Rumi poem that I discovered quite by chance when I was looking for a Rilke book. It struck something so deep in me that tears just started jumping out of my eyes.4 It starts off:

For sixty years I have been forgetful,

every moment, but not for a second

has this flowing toward me slowed or stopped.

That to me was so true. No matter how busy I am in my life, how distracted, how I pay attention to all the wrong things, that doesn’t matter, because the whole time, God’s goodness and presence is still flowing toward me without interruption. It doesn’t depend on anything that I do. Religion would have us believe that we have to somehow be good enough to get God’s grace or that we have to be serious and watchful, walking the narrow path. That’s just wrong. No matter how we are, God is there for us. We can never fully comprehend this, but even the slightest realization of that is just overwhelming. It is like this waterfall that we are standing underneath and somehow not even realizing it. But if you realize it for a tiny bit, then suddenly this experience brings a deep contemplative understanding that God is the host welcoming us all the time and we are the guests. Like the poem goes on to say,

Today, I recognize

that I am the guest the mystics speak about.

And the next line is:

I play this living music for the host.

Life becomes like a song instead of an effort when you realize that you are in God’s presence, and it’s not condemning but a welcoming embrace. And then the last line is:

Everything today before the host.

My whole life dances with this kind of freedom. I was in my fifties when I stumbled on that poem and thought that it was talking about my life. It was written eight hundred years ago, but it was talking about my life. Since then, I have read a lot of Rumi, Hafez, and other Sufi poets. They are extraordinary in terms of spirituality. Of course, they are coming out of the Islam mystical tradition, but I think it’s a wonderful gift that they are now, in the twenty-first century, being translated into English.

TOJ: That’s very beautiful, specifically at this moment when we have lived for so many years not being able to read each other.

ML: That’s so true. One of my coworkers at the Catholic Charities is Persian and her father was a Sufi scholar. He grew up, and at night his father would recite the poems to him in Farsi. He was the one that told me that someday I should look into them. I put it off, until one day I stumbled into Rumi, and since then, it’s been a great grace.

Notes

Click the images below to purchase these books from Amazon.com and help support Sister Marilyn Lacey (first image below) and The Other Journal.

1. Marilyn Lacey, This Flowing Toward Me: A Story of God Arriving in Strangers (Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria Press, 2009).

2. Shannon Presler, “Blood on Our Hands: An Interview with Sister Helen Prejean,” The Other Journal 14 (2009), https://theotherjournal.com/article.php?id=571.

3. See http://www.catholiccharitiesusa.org/, http://www.theirc.org, and http://www.jewishfamilyservice.org/Home/Services/Refugees-and-Immigrants.

4. All poetry quotes are from Maulana Jalal al-Din Rumi, “The Music,” The Book of Love: Poems of Ecstasy and Longing, trans. Coleman Barks (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2003), 15.