It is a rare and special treat to find a band that makes music, especially music that one might classify as religious music, which is wholly devoted to the pursuit of beauty. The Opiate Mass, a Seattle-based collaboration of musicians, songwriters, visual artists, audio engineers, and authors, provides just such a treat. In this interview, bandmates Zadok Wartes and Tara Ward muse over CCM, worship music, being in a band, and their need to write, create, and curate religious and intelligent music.

The Other Journal (TOJ): Please share with us how the Opiate Mass came to be. What was the band’s original intent, and how has it progressed thus far?

Tara Ward (T): The Opiate Mass was born out of a conversation—one of my bands had an album release, and Zadok met up with me, because he knew that musicians tend to get depressed after releases. He and I were riffing on the fact that both our bands were in some way coming to an end—though my band Late Tuesday is retired, not done. In the meantime, we were working at churches, and so we found ourselves discussing this sense of dissatisfaction that we have with both the music we do in bands and the music we do in churches.

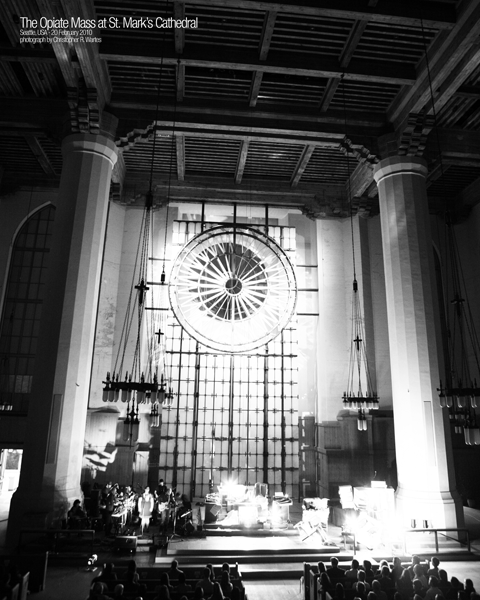

We had recently seen Sigur Rós at the Paramount in Seattle, and so we talked about how worshipful their music feels and about how our worship music, or even the music we perform in our bands, doesn’t get to feel like that. On Sunday morning it wouldn’t be appropriate to be that epic; you’d leave so many people behind. We mourned about how we don’t get to use our gifts in a worshipful way that often—it’s worshipful in the sense of leading others in worship, but it doesn’t take advantage of the full expanse of our talent, the glory of putting our fullest ability into something that is praise. We were also griping about modern worship, about the happy-clappy praise music that feels like an implant from the South or the East, and about how Seattle culture doesn’t seem to fit in this worship culture. We were amazed at the phenomenon of Compline at St. Mark’s Episcopal Cathedral, at how it’s more contemplative and how people who wouldn’t associate themselves with a Christian church still come and the church is packed every week.

And then we thought, “What if we did this thing where we were able to play the music the way we want,” and because we were also really tired of promoting our bands, we said, “We’ll play in the basement, it will be word of mouth, and we’ll make music for the joy of it. Then, maybe someday, we’ll play in St. Mark’s cathedral.” That’s what we wanted—epic, beautiful spaces to play in.

It started with all these ideas, and people became really excited. Zadok spoke to many people who wanted to be a part of this, and thus there was a growing sense of excitement over something we hadn’t even done. And I was talking to my friend Karen Ward at Church of the Apostles in Fremont, and she said she wanted to support us and could get us into St. Mark’s. We envisioned that we’d play there two to three years down the road, yet our first show was there—and 400 people showed up.

We’ve been doing this now for about two to three years, and we’re still figuring it out. We worked on music for a whole year prior to playing at St. Mark’s. We had this vision, and God fulfilled the vision. After our first event, we felt like we’d come to the end of a dream, but we were also wondering, what the hell are we going to do now? And so the last few years have been us attempting to flesh out how to keep doing this. And people still have this excited buzz about the music that causes me to marvel. Because it’s been birthed out of us just wanting to use our talents in a way we’ve never done before with people we like and respect. There is this buzz about our music being the next thing. People say extreme things like “This is it!” and I don’t even know what “it” is, so I try to have them explain a little more what they like or find so cutting edge. We’re still finding out ourselves, still developing our mission statement.

TOJ: How do people define “it”?

TW: Some people say that this is the direction that Christian music needs to go, which I don’t necessarily love.

Zadok Wartes (ZW): Most people ask, “Is this a worship concert?” I say, well, maybe. Some people say, “Yeah, it’s a concert, it’s art . . .”

TW: I hear a lot of people say that it’s the cutting edge of worship, but I don’t even know what that means, because worship is going to look different for different people.

TOJ: How do you write, arrange, and prepare for the next event? You each come with different gifts, approaches, and perspectives on music, so how do you make something that’s tight, that works, and that has its own sound that’s particular to you as a band?

TW: Being in other bands where multiple people wrote, I’ve learned that everyone has their own style and that style comes out through their personality. And so I think when Mark Mohrlang writes he’s more guitar-driven, and when Zadok writes he fleshes the music out on the computer and basically has it finished by the time he arrives to practice. I’ll write chords and melody and bring it to the band where we collaborate from there. The band shapes my songs and they make them whole. Zadok’s are usually fleshed out, and we recreate them as we step into the parts. Joel Eby is a really great chordist and figures out amazing chords.

ZW: He writes the most interesting music.

TW: I think what makes our sound cohesive is that each of us is using our strengths—my voice, Zadok’s voice, Mark’s guitar, Joel’s piano, and now we have more solid players: Kay Lambert’s cello, Ryan Davis’s bass, Lacey Brown’s drumming, Matt Chism on everything else—

ZW: Our rhythm section is funky. They wrote a couple bits for the last one that were incredible.

TOJ: I’ve been thinking through why we need to define and categorize art forms, and I’ve been wondering whether that’s the beauty of your band: that it’s something that’s not necessarily definable. And I remember you speaking about making music for beauty’s sake, beauty for beauty’s sake, rather than having this really intentional purpose and mission.

ZW: I come from a rock background, and when you’re playing in a club and you’re in a male band, there’s this sexuality, grit, angst. Maybe that’s why I like the idea of beauty. I think every artist is trying to make beauty in some way or another, but I had to be really intentional about it, trying not to be cool, trying not to be tough or to work up emotions that aren’t there. And this is related to the idea of celebrity—when we first started at St. Mark’s, we weren’t trying to perform. The aesthetic of Compline is that the beauty is more obscure; you don’t have anything to look at because the musicians are in the back of the cathedral. So we started with very little, but now I think we want there to be something to look at. Part of the beauty of watching someone create is the physicality of creating, and I still believe the entire evening should be beautiful. I think that’s the first adjective, and we’re very intentional about it. Although, when I say it that way, it doesn’t sound very profound because every artist is trying to make a beautiful record, a beautiful concert.

TOJ: Maybe that’s not true. What comes to my mind for your band is that there is an uncanny and natural expression coming from each of you and maybe that’s part of each person attuning to your strengths individually and realizing there’s something missing within your lives that you know you need to plug into, which is music that isn’t being manipulated by politics or having to find a particular way of doing things to please a certain audience. So maybe your posture with music-making isn’t informed by your audience as much as in other bands. Obviously you want people to like your music, but it doesn’t seem like it’s the driving force in what you are doing.

ZW: Oh, this is the most self-indulgent thing I could have ever dreamed of—I’m not kidding [laughter].

I’m absolutely addicted to what people think of me, and I won’t pretend otherwise. But if I were going to create music with no care for what others thought, then I’d ask, with whom, what would it sound like, and what would be the purpose? And the Opiate Mass is the answer to those questions.

If no one showed up to the first performance, I would have been totally depressed. But I wouldn’t want to do this with any other people, in any other venues, and I love almost everything we write. Tara is always bugging me to do a solo record, but I don’t have the desire. I’m making the music I love. I don’t want to play at Neumos or call up Easy Street Records and hope they care about my music.

TOJ: So what is it about what you’re doing that gives you this freedom? The location? Is there something you’re after that is different from traditional music venues?

TW: What we do is we create space for people to come into to interact with the music and the aesthetic, as well as having a time of silence, which gives space for people to feel and interact with themselves. This is what I hope, at least—that we’re singing in creation, we’re singing out to create space for the audience to feel whatever they need to feel. They’re going into a space, seeing art, and also experiencing it, musically or spiritually.

ZW: I think I know how we do space: we don’t engage with the audience at all.

TW: We don’t clap until the end. There’s not a lot of shouting. It’s more like a classical concert, which has a little more reverence in its format. I don’t know why we’ve kept doing it this way, other than that it feels right to not have clapping in between. The entire program becomes, in many ways, an entire song. If there were clapping in the middle, it would interrupt things. We’ve also made decisions in the past to cut things that would be distracting or shocking during the program.

However, after the last performance, I was talking with a guy who said he felt different things that weren’t contingent upon beauty; he felt war impressions and angst. I’m definitely a priest to the core—I’m all about nurture and care—but I think that’s also one of the dynamics that is coming out in this group, my voice and Zadok’s voice. The songs with my voice are more serene and emotional, whereas the songs with Zadok’s voice can be more war-like.

TOJ: That makes a lot of sense, if you’re the priest and he’s the prophet, that seems to be far-reaching for an audience. It seems able to meet people in many different places.

TW: There is a good balance. So our curated space is about beauty and it is a priestly thing, but it’s not all about these things—it’s becoming an encompassing space for people to interact freely.

ZW: I think calling something beauty doesn’t work because we can’t get to beauty without some drama. It’s not like every song is supposed to have resolution. For instance, we organize our program such that a song that’s darker or has more despair might go in the middle of the set.

TW: It’s beauty in the sense that many gorgeous paintings are centered on the play between dark and light. It’s not just clouds and heavens. It is tension and release: the music plays out what we’re going through.

TOJ: Having ambiguity in terms of the resolution is something that seems to be really important and distinctive to your group. Again, the notion of space, which we keep returning to, gives people room and an expanse to not necessarily clean up at the end and feel OK, but rather to remain and interact in the place that they got to after the program.

ZW: I’m thinking of times after our performances when people are wanting us to tell them what exactly a song meant. They’ll say, “What does that mean?” or “Why don’t you print out the lyrics? I can’t understand what you’re singing,” or “It seems like you’re singing about something important.” We had this video at one performance, and people told us that they didn’t get the video, and I said, “Well, neither did I.” I wonder whether we’ve been intentional about those choices to not care or need to know what our art means.

I keep thinking that we’re doing this unique thing, but maybe it’s not that unique, maybe all sorts of bands create stuff and don’t explain it. What happens on stage is we rarely engage the audience like a band at a club, where there’s clapping or a dialogue or laughter. Maybe it’s odd that people think there’s so much space, because we don’t have a connection—we don’t really care who’s there and we’re not trying to amp up the audience. We just have a seventy-five-minute set and we do that set. We don’t tweak songs or play an encore, and I don’t think people are used to the classical format of performance. But in classical music people will say, of course, you give the audience space—this is what classical music does.

TOJ: I feel as though you all are a muse for people, that you are a conduit for having a more spiritual experience.

TW: I think much of art is like that, where people ask “What does this mean?” When I get that question, I ask, “What do you see?” which frustrates people because they want to know how this process came out of you. There might have been a specific reason, but the creation of art mimics how God created and sent something out from himself. It mimics childbirth, in that children must then go off and have lives of their own. Part of the process of art is what it creates in other people, and I don’t mean to sound wishy-washy, but there is an overall sense with the Opiate Mass of “think for yourself.” A lot of religious music is based on people wanting to be told what this means. They want to know that this is who Jesus is, this is what Jesus meant. Well, I want to know what you think and what surfaces in you and your relationships.

People speak about art and science as different ways of knowing; they say we can’t have one without the other. But I think many religious people want to know only the traditional way of thinking. I’m not interested in a scientific or theological lens of knowing and revealing what a song means. Art is a different kind of language and it stirs people in different ways.

TOJ: When people enter into a place where there isn’t a lot of answers or resolution per se, where the emphasis is on expression, that seems to give people the right to visit places that are sometimes more emotional and troubling. There’s something about being within a group, in this setting, that feels safer, perhaps a collective admission to feeling things that might not otherwise be comfortable, things that might typically be avoided. In some ways your band is parenting people into necessary places of experience, artistically and spiritually.

I also wanted to touch on something we discussed a few weeks ago. For a lack of better words, you’ve heard testimonies from people who are atheists or deeply struggling Christians. And devout religious people come into the same room and somehow find commonality, or at least the baggage of religious difference seems to be somewhat suspended. I’ve wondered what has enabled these different people to be in the same room, especially when your songs can be overtly Christian, like a hymn, or very ambiguous in a way that can disrupt the devout Christian.

TW: I have heard many people say, “I would feel comfortable bringing my atheist friend here,” and I have mixed feelings about that statement. I completely want that, yet at the same time, it reminds me of growing up, when people said, “We’re having a concert, and you can bring your non-Christian friends too!” I don’t hope that our performances are safe for non-Christians; what I hope is that the music is beautiful. For instance, Bob Dylan can sing blatantly Christian songs and people still love it. The church sometimes tries to put the stamp of ownership on things. We say, “This is Christian. This is our stuff. This is our music and you outsiders can listen to it because it’s awesome and you’ll like it.”

ZW: That’s probably why we rotate venues for each performance.

TW: I would like more people to be able to hear our music. I’ve always believed as a musician that no matter what I’m singing about, something happens when I use my voice. Even if someone is sitting at a coffee shop and they hear someone’s voice over the radio, it can have an impact.

ZW: Why do Christian artists want non-Christians at their shows? Tara, why would you want non-Christians to come to our shows?

TW: I would like all living people to come to our shows.

[Gales of laughter.]

ZW: OK, OK, of course! We’re inbred right now because we’ve only done word-of-mouth promotions, and Christians in Seattle are friends with other Christians. So why don’t we take an ad out in Seattle Gay News? Are you OK with us being inbred? We haven’t worked to promote this outside of our own circles. Why?

TW: Because we didn’t want to promote, period. We’re at a crossroads right now.

TOJ: Well, this could be a good transition in light of our present celebrity issue.

ZW: From day one we weren’t going to put our faces on this. No band photos, no saying things like, “Featuring Tara Warrrrrd from Late Tuesday.”

TW: We were so burned out, honestly, on the band machine. We didn’t tell anyone where the shows were going to be, you had to find out on your own.

ZW: A very weird kind of fascism.

TW: We’ve had to change our tune because this has grown into something life-giving and we want it to continue. We’ve had to wonder, “Maybe people would like this—dare we send it to the radio?” This is not what we were about in the beginning. People do get worried about us losing what we started with and the thing is that we don’t even know what we started with. Well, we started at Omega, at the end, at the end of our vision. So it’s kind of an exciting ride from here, every step is beyond the end, since we began at St. Mark’s.

ZW: Which was a letdown—“Oh, we’ve already played at St. Mark’s.” It’s like the kid that won an Oscar in The Piano when she was ten, Anna Paquin.

TW: I think the dangerous thing is that we can talk a lot of shit. We can say a lot of things, which make it seem like we know what we’re doing. Every once in a while I wonder what are we doing. Why are 300 to 400 people showing up?

TOJ: Have you had opportunities to sell out?

ZW (chuckling): I remember the week of our first show, Nathan Marion, the founder of the Fremont Abbey Arts Center, came up to us and said, “Don’t let anyone buy you out, because we want to buy you out.” It was sort of tongue in cheek. There aren’t a lot of opportunities; it’s not like Dove Records came to us and wants to put our record out. I mean to a degree, we’ve had plenty of churches with less than desirable spaces e-mail us and want us to play.

TW: I think we’re still trying to understand what “selling out” means. We’ve definitely struggled with what it could mean. Does it mean taking a worship grant from Calvin or anyone interested in giving us money or wanting to support us? We want churches to feel like they can support us, but we always have to ask questions. Is this tied to a certain domination? Will this turn certain people off? I really believe the church should support artists like us, but there are always so many political implications—it’s difficult for them to do it and difficult for us to take it. I wish it were easier.

Something else to go along with what’s been said already is that we’re not a church. We’re not trying to shepherd people. What we’re doing is very spiritual. We are trying to be celebrities. So that can fit into this issue at The Other Journal.

[Laughter.]

ZW: I don’t want to be a celebrity. I don’t know why I’m on stage.

TW: Your messages are conflicting. In the beginning of the interview, you say this is the most self-indulgent thing and that you really care about what people think of you. And now you say that you don’t want to be a celebrity.

ZW: No, no, no. I meant that what I care most about is the music, what we create. I don’t care if anybody shows up; this is what I want to do. I really mean that.

TW: So you do care what people think?

ZW: I care about what people think. If people came up to me afterward and said, “That was horrible. I can’t believe you guys did that,” we’d never do that again. I need positive reinforcement, but the initial push on this was about what I wanted to do. I don’t care if this is a hit. And yeah, I don’t want to be a celebrity because that is a tormented life when there’s that much attention and that many opinions about you, people saying you suck. I don’t like that, but I don’t know why I’m on stage singing. I guess I like singing. I should be a studio singer in Nashville.

TOJ: Well, it seems like at this point you all are probably fairly confident about your sound and what you’re creating and generating. In a sense, then, if no one attended a show, do you think you’d still believe in what you’re doing?

TW: I think the key thing for me is that this is fun.

ZW: So if eight people show up—

TW: Eight people are not going to show up, that’s the thing. But if no one showed up, sure, we’re creating the space for ourselves. We played together for a year before playing for anybody, and it was fun for us. But it’s a lot of work having sound people, lighting, and all this stuff. The fact is that other people get to enjoy it and feel impacted by what we share.

I think the “why” is that I enjoy doing this. There are points when it can become unenjoyable, for example, by saying “yes” to too many things you don’t really want to do.

TOJ: Or becoming confined to a certain denomination—it seems like you guys are trying hard to not become constrained by things that are external from your “why.”

TW: Exactly, and that’s why I’ve pushed Zadok to do a solo album. Because he’s a prophet by nature, I feel like he gets confined by the group as a whole. The Opiate Mass is more about my desire to have an outlet in which we’re not confined. It’s not so much that I don’t like a song by Zadok, but maybe the song doesn’t work as a group. For me, personally, when those experiences start to build up, that’s when my secretive desire of needing another outlet arises. If you don’t have particular outlets, those feelings begin to build up and—

ZW: You have a kid. You make a baby.

TW: And you find yourself creating what people want and being driven by something other than what started the band. I’ve been thinking more and more about how I’ve lost the ability to be a good fan. I want to learn how to be that again because I became embarrassed along the way. When people got embarrassed over me getting excited about something—

ZW: Are you talking about the Lion King?

TW: Like Sam Phillips. I was really excited about meeting her, and some people had a reaction toward the excitement. It’s a really interesting concept for me to consider the difference between the idolizing we do with celebrity and the really good aspects of being a fan and allowing yourself to really like something or someone. And then I struggle with fan pages. I removed all my fan pages from Facebook because it drives me nuts—I can’t be a fan of everyone’s music; that’s not honest.

ZW: I deleted my whole account.

TW: There’s a tension in learning how to be a good fan and enjoy other people’s art and music again, genuinely. I call it a theology of abundance because a lot of times we, as artists, begin to have a theology of scarcity, where someone is doing this so I can’t do that. I can fall into that sometimes, and so I want to practice being a genuine fan of other people and not having it be about someone creating something good which then means I can’t create something good as well. I’ve been treated that way before, where we can’t rejoice with each other in what we are creating. Another part that draws me to celebrity is that I want to be friends with these people. I become tongue-tied around them because they’re doing something I admire. But then I lose sight that I’m important too, the non-celebrities are also important. We can relate to others through what we do well and become recognized for it and that’s great.

ZW: I don’t want to be disappointed by celebrities.

TW: I think a lot of people are and I think that’s interesting too. I remember a long time ago reading Keith Green’s No Compromise, which talked about how he and his friends loved Joni Mitchell. They felt she had the answers to life through her music because a lot of us can feel like that from musicians. They write things that feel like they crawled into our souls. I remember they crawled into her place and she was smoking pot, so they all smoked pot with her and realized afterward that Joni Mitchell doesn’t have the answers to life. It can be disappointing. I was talking to someone who used to love Jimmy Carter, thought he was such a great guy. I guess Carter would carry his own luggage while traveling and later people discovered that it was empty luggage. It’s little things like that which disappoint us, and when we find out things that disappoint us, they may change the way we feel about what they do. Sometimes it is attached to the character of someone and sometimes it doesn’t matter.

TOJ: I think it goes back to iconography. Iconographic paintings are supposed to be flat in order to take the viewer beyond the painting, to something greater. This notion seems important, that images, songs, words should be conduits.

T: A window. It takes you somewhere.

TOJ: I believe that’s what your music has done.