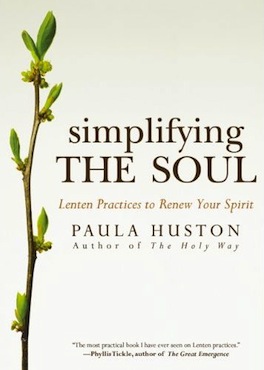

Paula Huston, a Camaldolese Benedictine oblate, is the author of numerous books, including Forgiveness and The Holy Way. In her new book Simplifying the Soul: Lenten Practices to Renew Your Spirit, Huston offers daily exercises that can help achieve simplicity of heart, soul, mind, and environment. In this interview, she discusses lessons contemporary Christians can learn from the desert fathers and mothers, the difference between Lenten practices of simplification and deprivation, and the tension of living a contemplative life amid the noise and clutter of our daily routines.

The Other Journal (TOJ): What first drew you to spend time living among the monks in a monastery?

Paula Huston (PH): I was introduced to New Camaldoli Hermitage by a friend, and I doubt I would have ever gone on my own. The only thing I knew about monasteries came from my Lutheran upbringing: I’d heard that Martin Luther held a pretty dim view of this peculiar lifestyle, but that was about it. Then, when I was seventeen, I lost my faith entirely. For the next two decades I had nothing good to say about Christianity, and when I first met the monks, I’d only just begun to reassess that long-held position. I was opening up and longing for some kind of relationship with God, but I was still absolutely terrified. I’d been in the academic world for years, teaching, among other things, spiritually bleak modern literature, and without even realizing it, I’d come to see life through this lens. I was intellectually armed against theological argument and emotionally fortified against spiritual trustfulness. And I didn’t know how to get past all that.

The monks had an absolutely radical effect on me. They did not preach; they did not argue; they did not even talk with you unless you asked for a conversation. All this calmed my fears. Nobody was going to proselytize or force me into an either/or choice. Instead, they simply welcomed my presence as they went about their business, which was, in the words of St. Benedict, ora et labora or “prayer and work.” Four times a day the bell would ring, and here they’d come in their white Camaldolese robes, filing into the chapel for the chanting of psalms, the reading of Scripture and patristic literature, and the prayers of the faithful. They’d bow, they’d stand, they’d sit in silence. During vespers each evening, the prior would dip a leafy branch into a basin of water and bless us all—even those of us who were still on the theological fence, like me. Apparently, monastic blessings were for everyone. I could not get enough of this place where solitude and silence, peacefulness and loving-kindness, were the norm. I felt like Alice, who’d stepped through the looking glass into a whole new realm, and during the following years, I’d come back over and over again until I finally became a vowed oblate, or a lay associate, of this very special community.

TOJ: What can a monastery—a community with rhythms intentionally set apart from the world around it—teach Christians who are interested in a theology that’s conversant with culture?

PH: From its earliest beginnings in the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, monasticism has offered a particular way—one way among many—of undergoing the radical sort of transformation that St. Paul was talking about when he said that we were meant to put on the mind of Christ or what Jesus was referring to when he said we were to be “perfect” as our Father is perfect.[1] Monastic wisdom would gently offer that, without ever losing sight of our inherent human propensity to self-deception and sin, we can indeed learn and we can indeed change for the better, all without falling into the trap of hubris. How? We embark on a program meant to teach us who we really are, one in which we do certain things in order to discover certain things. We attempt to fast, for example, and find that we are completely addicted to burgers and fries or Starbucks frappucinos. We attempt solitude and learn that we need a fairly large audience around us most of the time in order to feel alive. We attempt frugality and realize for the first time how married we are to our credit cards. This new knowledge about ourselves can be chastening in a good way; it can lead to humility, which means the ability to see ourselves clearly. No longer deceived by grandiose fantasies about our own importance or, conversely, riddled by self-hating shame, we are freed up to love in a way we cannot when the ego is still running the show.

So the seemingly archaic practices and rhythms of monastic life are really just a way to gain some kind of control over habitual behavior and thought. And if we are going to be effective witnesses for Christ from within culture, whether as cultural critics or culture shapers, we must be willing to look with a clear eye at the habitual patterns of behavior and thought that dominate our society. If we’re to avoid hypocrisy, however, we must first be willing to turn the same assessing gaze on ourselves. This is where I see monastic practices intersecting with contemporary cultural concerns.

TOJ: Lent is often considered to be the season one deprives oneself of something, usually chocolate or television or coffee. At their best, these abstentions can remind us of Christ’s suffering, but more commonly they become a token observation of the season. Your book invites readers into a life of simplicity but perhaps paradoxically, not a life of deprivation. Can you explain the difference?

PH: The voluntary deprivations of Lent may indeed be reminders of Christ’s suffering, but I believe that their real purpose is more strongly connected to this ancient Christian wisdom about how we get to know ourselves as we really are, including the parts we’d rather not acknowledge. Thus, deprivation per se is not the point; the real point is to in some way pit ourselves against ourselves to see what we can discover. The desert dwellers of the third and fourth centuries conducted running experiments on themselves to find out what sorts of spiritual obstacles they were throwing in their own paths. The commitment to celibacy revealed pretty quickly their true relationship to sex, for example. If they discovered that most of their attention was taken up by lustful fantasies, then that was going to be a real problem on their particular spiritual path. They had to deal with that—usually through the practice of regularly revealing their innermost thoughts to a wise elder—before they could move on. The same held true for those who could not stop worrying about security issues, for those who worried that when they were old, decrepit monks no one would care for them if they didn’t stash gold under their mattresses. If they allowed themselves to hang on to that gold because it made them feel safer, they’d never learn what they needed to grasp about trust as an aspect of faith. As they slowly began to shed their propensities toward gluttony, avarice, anger, self-pity, et cetera, they became simpler, more integrated, more focused people. The deprivations that seemed so difficult at the beginning of the process were no longer an issue; those things were usually no longer important to them. They’d found something better.

I don’t think we are any different than those third- and fourth-century desert dwellers were. What initially might seem like a really tough sacrifice—say, giving up obsessive social networking for an extended period just to get our heads on straight—begins to feel natural, right, and good once we begin reaping the spiritual benefits of this supposed deprivation. We’re no longer enslaved by a mindless habit. We can think about other things. We can pray with more focus and intensity.

TOJ: The church often fights a temptation to reduce faith to an ethical commitment. And while the church likely wouldn’t acknowledge a works-based salvation, there is an implicit assumption in our sermons and communal language that one’s faith compels – or at least ought to compel – a particular orthopraxy. How does one practice a Lenten simplicity in such a way that it becomes merely an icon of a faith practiced well?

PH: I think the same logic holds here. The important thing to remember is that the practice of a spiritual discipline, whether it is fasting or almsgiving or whatever, is not about earning spiritual brownie points. Instead, it’s about clearing the pathway of obstacles of our own making in order to be able to move forward. We are constantly getting in our own way, working at cross-purposes. I used to feel as though I was living in the middle of an internal civil war. I spent so much time arguing with myself about what I thought I wanted versus what I knew to be the better way. I spent even more time trying to rationalize behavior that kept me self-occupied and in a state of avoiding God. What kinds of behavior am I talking about here? Nurturing a grudge, rather than forgiving. Going on an eating binge to compensate for frustration instead of directly solving a problem. Telling a self-protective lie rather than accepting the consequences of my act. Spreading gossip instead of protecting another person’s reputation. Wallowing in self-pity instead of acknowledging my own poor choices.

Lent, I found, provided the perfect opportunity to spend some time with these willful tendencies of mine, really getting to know how thoughts like these got going in me and acknowledging to myself and God that they were not helping and I’d like to be rid of them—not in the sense of pulling myself up by my own spiritual bootstraps, as Pelagius so blithely and wrongly recommended, but as a humble act of faith. Jesus taught some very specific spiritual practices, and I think he meant for us to take those seriously. For example, he taught us to seek out a brother who is angry with us, even unjustifiably, and to ask forgiveness with the goal of reconciliation; to not judge others by a different and far harsher standard that we judge ourselves; to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, care for the sick; to practice what we preach. Trying to live in the way that Jesus not only modeled but also commanded does not seem to me to be an act of pride but rather a sincere attempt to obey him. To, at the very least, do what we can to clear away self-generated obstacles so that grace can more easily work its way with us.

TOJ: Some of the reflections in your latest book require a great deal of self-awareness to complete, a kind of awareness we’d all be lucky to have! What role does the community play in cultivating this self-awareness for the sake of a life of simplicity?

PH: Community is essential for several reasons. First, it is essential because we learn by imitating others. We almost can’t help following the crowd (try yawning in a roomful of people). At some deep and mostly unconscious level, we very quickly pick up what the social mores are—what’s expected of us if we are to fit in, what we can and can’t get away with saying or wearing—and from then on we work very hard to comply. Monasticism knows this too, which is why they form a deliberately alternative lifestyle. To learn new ways, monastic tradition says, you must enter a totally different kind of community and begin imitating different kinds of behavior and ways of thinking.

Second, we need community because it makes us accountable. As long as our spiritual efforts are completely private, it’s easy to let them go when the going gets rough. If, on the other hand, we’ve committed ourselves before others, even if it’s only in front of a like-minded friend, then it’s automatically harder to bail out on the enterprise.

And third, a community can provide really helpful feedback along the way. One of the most difficult challenges we can ever face is learning how to see ourselves clearly, getting past the fantasies and the wishful thinking and the self-deception to find out who and what we are bringing before God. A good soul friend, or community of them, can act like a mirror when our own vision is still muddled.

TOJ: As you’ve interacted with the readings of the desert mothers and fathers, how do you see their asceticism speaking to a post-Christian culture?

PH: I think I’ve probably already answered this in various ways throughout this interview, so I won’t repeat myself here. But what struck me about your wording is the term post-Christian. If we really are living in post-Christian times—and I’m not necessarily convinced that we are, though it’s an interesting theory—then it would seem as though radical measures are called for. People who have become jaded and cynical about the way that contemporary American Christianity has been expressing itself for the past twenty-five years aren’t likely to be drawn back in by more of the same. Like me when I first visited the monastery, they’re going to be well armed against theological argument and emotional or sentimental manipulation. They are going to (wrongly) believe that they already know all there is to know about the Jesus thing, and they’re past all that. What they don’t know, however, is what’s next. My sense is that they’re not thinking too hard about that question but, rather, simply trying to stay afloat and find some happiness along the way, whatever that may mean to them individually.

The asceticism of the desert dwellers, should it ever come to be more widely known, could thus act on jaded ex-Christians or never-Christians in the same way that my first experience of the monastery acted on me: as a startling proof that I didn’t know all I thought I knew and that here were people who were willing to live in a truly radical way in order to pursue something that was obviously deeply compelling to them, people who were willing to commit to this path for life, to give it their all. In an era like ours, where commitment is too often equated with losing out on interesting options, I found this really astonishing. They were a cipher to me, a mystery, and most of us—even in the sophisticated, postmodern world—cannot resist a good mystery.

[1] See Matthew 5:48.