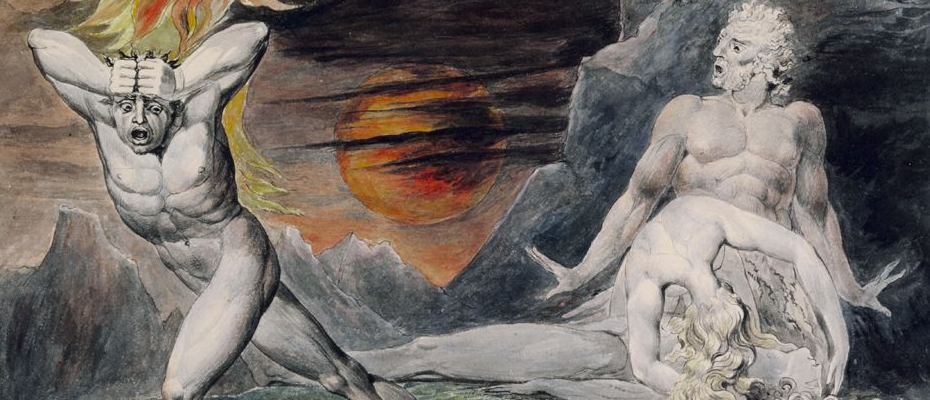

As the parent of a two- and five-year-old, I have learned to play the role of late-night interpreter, to differentiate the wet-bed whimpers, the nightmare shrieks, and the hungry screams. I’m also learning to recognize my own reactions to these cries, to acknowledge my frustration at the disruption of my sleep, and to then resume the role of loving father. As I’ve grown as a father, I’ve come to believe that healthy people are characterized by their ability to perform this same kind of dual listening—to hear their own cries of frustration and need andto also respond to the cries of another person or neighbor with empathy and solidarity. As a black man from the South, I have come to see that the legacy of white supremacy in the United States is a story of the failure to hear and respond to the racial cries of broken bodies and spirits. Violence, oppression, hierarchy, tyranny, and inequity of any kind are the results of the refusal to feel and interpret and respond to one’s own cries and to the cries of the other. If we listen carefully, we can hear these cries in the ways we speak to our spouses, engage our children, and relate to our siblings. I am reminded of the ancient story of Cain and Abel, brothers torn apart through mishearing each other’s cries.

The Silent Cry

The source of violent inequity is always the perpetrator, and at the heart of every oppressive regime is the perpetrator’s presumption that they cannot be denied. In the story of the first biblical murder, Cain kills Abel because he cannot accept that God rejects his sacrifice; he cannot accept being refused. This is a cry for recognition, significance, and belonging, yet Cain can’t hear it. He can’t hear his own cry.He is prey to the perpetrator’s refusal to cry, to hear others’ cries, and to respond with sensitivity.

James Baldwin is helpful in exposing this overlooked chasm at the heart of the perpetrator; Baldwin has influenced me to ask: “What made white folks believe they needed a nigger in the first place?”1 White supremacy, he suggests, is the original regime of inequity in the United States, and it is what develops when we allow immaturity to be a virtue, when we never expect white people to grow up or to listen to their own cries and address them directly rather than through the subjugation of others. This is not unlike Gregory of Nyssa’s definition of sin as the refusal to grow.2

Perpetrators will often go to great lengths to avoid their own cries. In terror that this immaturity will be exposed, white people have castigated black and brown people as impure and acceptable to kill. And this same fear has made people like Cain shirk the responsibility for their actions. “Am I my brother’s guardian?” (Gen. 4:9 NLT) he asks rather than confessing. It’s the same fearful deafness that makes people sigh and say, with little sense of their own culpability, that things might be better if black people would stop killing each other, or poor folks would quit being lazy, or women would quit dressing so provocatively.

The silent cry is the true conscience of Cain, or of any perpetrator. It is a cry that recognizes that the one the perpetrator is about to violate is their own kin.

The Generational Cry

Dismantling violence and inequity cannot be reduced to personal decisions. The vicious spirit at work in Cain was at work before Cain was born. When Eve gives birth to Cain, she says that “with the Lord’s help” she has produced a man—not a son or a brother, as Abel is affectionately described, but a man (Gen. 4:1). Ancient commentators are helpful here.3 They see in Eve’s words an allusion back to the story of Eden, a story in which family relations are woven inside of repression, distortion, and violence. Cain is unknowingly sounding a generational cry; he is part of a generational spirit of hierarchy that must be faced—or listened to—in order to be overcome.

This is not unlike the spirit of white supremacy in the United States. In the late nineteenth century, European immigrants to these native lands chose to become white. Like their earlier fair-skinned kindred that stole the land, labor, and life of Native Americans and African peoples, the new immigrants sought to prove themselves in the fight for whiteness. The reward of whiteness was not unclear—a chance at the middle-class lifestyle—and so they consciously chose whiteness in the halls of their homes and in the streets of their neighborhoods, refusing to sell homes and property to people of color. They consciously chose to not let their kids mix and mingle with black kids. As Brando Starkey indicates, “With these new [European] immigrants living in the same neighborhoods, intermarrying, attending the same schools, mingling, and most importantly committing racism against black folk, through successive generations, they became white.”4 In this way, whiteness is a generational social construct that has been honed as a weapon against people of color. There is no such thing as white; it is instead, as James Baldwin illumined, merely a synonym for power.5

Today, so-called white people—that is, those of you who through generational posturing and policing have become white—must listen to the generational cry. When did your people decide to become white? What did they do to achieve it? And what did it do to their souls—to your soul—to become white?The blood of those slaughtered by white supremacists cries from the land, from the family photo albums, from the stories you neglect to tell about your ancestry. Claim your people. All of them. Not just the ones who vote like you do. They are all your people! Until you address the white supremacy among your own people, you undermine the authenticity of any cross-racial relationships you have or social justice work in which you engage.

Your people have written and theologized the most about the gospel. The gospel says that I am with you, yet your people have done everything within their power to divide and conquer, and this invisible history has stopped your ears from hearing your own silent cries, as well as the cries of black and brown people.

Like the healing that God offers Cain, people of European descent must face what it is your ancestors desperately needed so that you can come to terms with what you now need to be whole, to be liberated from whiteness. This isn’t about the right technique. This is spiritual. Your healing awaits you. And you have the sacred text. See yourselves as the perpetrators in every single story, not as righteous protagonists or victims. See what deliverance looked like for the communities that were the oppressors.

The Silenced Cry

Abel never speaks, but his blood cries from the ground. The land acts in solidarity with Abel. Where Abel cannot speak, the land speaks for him. The cry of Abel isthe cry land of the land.

In silencing Abel, Cain chooses to not hear the cry of the land. What irony—the one who works the soil is estranged from it. Cain’s technical expertise cannot assuage the spiritual wandering, the psychic estrangement that results from never facing his own cry and silencing the cry of his brother. Knowing the strategy to work the ground is not intimacy with the ground any more than the contemporary seduction of progressive strategy puts one on the ground in solidarity with sites of violence. The ground stands with those whose innocent blood it has received at the hands of oppressors.

People of color and their allies have long been in tune with the cry for justice. We have long been acquainted with the silencing of that cry on all fronts, by liberals and conservatives alike. But have we been in harmony with the reverberation of our cries taken up in the melody of the land? In addition to denying people of color justice and distorting European peoples’ connection to the earth, white supremacy has also stripped people of color from the land. Land is an estranged mother to us. It has been made property. Theologian Willie Jennings describes “the grotesque nature of a social performance . . . that imagines . . . identity floating above land, landscape, animals, place, and space, leaving such realities to the machinations of capitalistic calculations and the commodity chains of private property. Such . . . identity can only inevitably lodge itself in the materiality of racial existence.”6 To treat the earth as property is thus to reinforce white supremacy.

People of color and our allies must therefore be vigilant that we detect the consumerism which so easily besets our work for equity. This is evident in our use of the language of privilegeand reparations. The plunder of empire and white supremacy is not a privilege: it is a death trap for so-called white people. That is why we must be careful with reparations talk. Liberation is a disciplined work, and part of that discipline is having eyes to see and hearts to discern that what people of color want returned to us are not the death traps of privilege. I don’t want privilege if it makes me believe I’m better than where I come from and from the majority of black and brown people in this world. I don’t want privilege if it puts me in competition with my people, the land, and the places that I long to nurture us instead of destroy us. Privilege is a death trap for us all. The seats of pharaoh’s Egypt are not the places of plush and welcome provided for us by Mother Earth.

Establishing equity is not about securing greater status or more stuff. Equity is about radical self-love that connects us to one another and to the land of our dwelling places. To my people of color: Do you knowwho you are? Do you know who your people have long ago told you that you are? We are a relational, covenantal, community-based, land-oriented people. We are people who experience the sacred in everything, people who have what we need and are generous with our neighbors. That’s who we are! To repair what white supremacy has stolen does not require a crude inversion of positions; it requires a return to the forgotten ways of land, of neighbor, of the stillness to hear our hearts beat, to hear our souls cry.

People of color all across this country are returning to this forgotten way, returning to the truth that those who walk this narrow way will lead the world into the beloved community. Whether your skin is fairer or darker, recovering the silenced cry is about choosing the path on which you stand. Do you stand in the soil that can nurture us all or are you floating above the land seeking your own advantage? As bell hooks puts it: “It’s not a question of whether you’re gay or straight or black or white: what do you stand for? Who are you? How can you know that—and operate from that position of power?”7

The Cry of Joy

The author of Hebrews places Abel among the cloud of faithful witnesses:

By an act of faith, Abel brought a better sacrifice to God than Cain. It was what he believed, not what he brought, that made the difference. That’s what God noticed and approved as righteous. (Heb. 11:4 MSG)

Abel was not erased. Abel cannot be erased. Abel’s righteousness was not in his performance. His righteousness was his trust in the divine presence with him through creation, reminding him of his own belovedness. In the same way that the ground claimed him, so too the divine claims him throughout the ages. The cry of Abel is one with the cry of the land, which is one with the cry of the divine. This interconnectedness is resurrection; it is joy inside of terror. Abel’s unearned suffering is redemptive in this life—Cain’s violence does not define Abel. Abel stands liberated among the ancestors. He stands among my African ancestors who refused to be defined as slaves, who through the spirituals sang out cries of joy while surviving inside the tyrannical regime of chattel slavery. Their cries of joy too were their liberation.

The ancestors’ liberation is an invitation to us in this moment, to ask ourselves where we stand. Are you standing on ground that has been tyrannized because you have not come to terms with the blood which it has swallowed? Or are you standing devoted to the places and people and dirt that you inhabit? From the variety of our proximities to the origins of our cries, the invitation is to free our cries to sing new songs of joyful liberation, tied to land, to the divine, to the stories of our people.

- See Baldwin in I Am Not Your Negro, directed by Raoul Peck (2016; New York City, NY: Magnolia Pictures).

- See Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses, trans. Abraham J. Malherbe and Everett Ferguson (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist, 1978).

- See Andrew Louth, ed., Genesis 1–11, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2001).

- Starkey, “White Immigrants Weren’t Always Considered White—and Acceptable,” Undefeated, February 10, 2017, https://theundefeated.com/features/white-immigrants-werent-always-considered-white-and-acceptable/.

- See Baldwin in I Am Not Your Negro.

- Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 293. It is important to note that Jennings’s critique is of the capitulation of Christian identity to the intersecting oppressions of white supremacy and capitalism, which renders disconnection from creation. However, Jennings’s critique applies more broadly to any socially constructed identity in the United States. Any social identity in the United States is subject to disconnection from the land to the extent that it does not intentionally challenge and dismantle the elusive power of the intersections of white supremacy and capitalism.

- “Noted Feminist bell hooks No Longer Supports Hillary Clinton,” 2016, video, 1:11, https://blavity.com/noted-feminist-bell-hooks-no-longer-supports-hillary-clinton.