I am a lifelong believer in Jesus who spent the better part of his early Christian experience terrified of eternity. My worry, mind you, was not for the reasons you might suppose. I have never, as far as I can remember, been seriously frightened by hell or the apocalypse. I know that many religious people panic over such eschatological matters, and as a pastor who has counseled and prayed with a good number of those folks, I can appreciate those fears. They are real.

Instead, I was frightened by heaven. The eternity I learned about as a child was a place in which everything had already been accomplished, a heaven in which there was and could be no tomorrow. I tried to imagine it, conjuring images of my friends and me loitering about streets of gold. I imagined us hanging out in large heavenly backyards with no clear sense of purpose because, of course, people without a future cannot, by definition, have a sense of purpose. Although I could not articulate it as I am here, I remember feeling that such a lack of purpose would not be a fulfillment of our humanity but rather its destruction. In such an eternity, human life as a willing, hoping, desiring, acting thing, screeches to a terrible, final halt and is nullified by the great End for which we were supposedly made. What could be more horrible than to arrive at the beatific vision, only to discover it to be not your final blessing but rather your annihilation?

As I considered this further, it struck me that even my vision of eternal, purposeless loitering was logically impossible: if there is no future in eternity, then there can be no succession of moments, no movement, no loitering. Eternal life with God was beginning to look more grim by the second—futureless, purposeless, and frozen. How this was different than the eternal death we knew as hell, I could not say.

Fortunately, in the Christian faith, our symbols for life in the hereafter are, for the most part, appreciably better than what I inferred as a ten-year-old about that final destination. The great Isaianic vision touches our deepest hopes and longings. The Lord declares, “But be glad and rejoice forever in what I will create, for I will create Jerusalem to be a delight and its people a joy. I will rejoice over Jerusalem and take delight in my people; the sound of weeping and of crying will be heard in it no more” (Isa. 65:18–19 NIV). Isaiah is clearly describing here an eschatological state that has all the marks of temporality. He goes on, “They will build houses and dwell in them; they will plant vineyards and eat their fruit. No longer will they build houses and others live in them, or plant and others eat. For as the days of a tree, so will be the days of my people; my chosen ones will long enjoy the work of their hands. . . . The wolf and the lamb will feed together, and the lion will eat straw like the ox, and dust will be the serpent’s food. They will neither harm nor destroy on all my holy mountain, says the Lord.” (21–22 and 25) Here is a glimpse into the great end for which we were made that stands in contrast to what I imagined as a ten-year-old. It is a vision of God and humanity gathered up together in joy forever consummate and consummating, young and old flourishing together under the gaze of the Almighty, engaged—and this must be highlighted—in meaningful activity. They build houses and plant vineyards and raise crops and cattle and are permitted, in a way that we are not now, a full enjoyment of the work of their hands. In Isaiah’s dream of the end, there is, odd as it may seem, a sense of future, a moment by moment expectation of good that is not yet possessed. Imagine: there is anticipation, even in the new heavens and the new earth.

John, writing in exile from the island of Patmos, longing himself for the coming kingdom of God, expands on Isaiah’s vision:

Then I saw “a new heaven and a new earth,” for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea. I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. ‘He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death’ or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.”

He who was seated on the throne said, “I am making everything new!” Then he said, “Write this down, for these words are trustworthy and true.” (Rev. 21:1–5)

And lest we think that this dwelling of God with men precludes a sense of a meaningful future, John rushes to add:

I did not see a temple in the city, because the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are its temple. The city does not need the sun or the moon to shine on it, for the glory of God gives it light, and the Lamb is its lamp. The nations will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bring their splendor into it. On no day will its gates ever be shut, for there will be no night there. The glory and honor of the nations will be brought into it. Nothing impure will ever enter it, nor will anyone who does what is shameful or deceitful, but only those whose names are written in the Lamb’s book of life. (22–27)

Here, as in Isaiah, we have a sense of movement, of purposeful, and thereby meaningful, human activity in the new heaven and the new earth. Things can happen there that had not previously been so, which means, of course, that there is a strong sense of anticipation and expectation in the new Jerusalem; there is the sense of an ongoing future, even in the world to come. Time—our abiding awareness of continuity between a completed past, a genuine present, and an expected future—will not have come to an end in the hereafter. Rather, time will have been elevated and transformed.

Saint Augustine, in his own vision of the end, seems to have been very much in accord with Isaiah and John. In the final pages of book 22 of City of God, Augustine reaches staggering poetic and theological heights. There, in that final city, we will be “made partakers of his peace.” We will participate in the life of the triune God. We will live into the theosis transformation process posited by Eastern Orthodoxy. As Augustine continues, “Wherever we turn the spiritual eyes of our bodies we shall discern, by means of our bodies, the incorporeal God directing the whole universe.” These are active verbs—we see that God will be busy in the eschaton, guiding and directing all created things into the dynamic harmony of God’s own uncreated and ongoing blessedness, such that our internal “harmonies which, in our present state, are hidden, will then be hidden no longer.” Our “rational minds” will be kindled “to the praise of the great Artist” and there “we shall see and we shall love; we shall love and we shall praise. Behold what will be, in the end, without end! For what is our end but to reach that kingdom which has no end?”1

Augustine’s vision in City of God is a fully participatory eschatology. It is the removal of the cosmic dissonance caused by sin so that created reality will finally find its home in the great music and artistry that is God. Augustine dreams not of the destruction of time but the transfiguration of time so that we might participate in God’s own time.

A breathtaking vision, no doubt; but I’m not certain Augustine is ready to relieve my ontological paralysis. Suppose we ask him the next obvious question—what then do we mean by God’s own eternal time into which created time is finally welcomed? How do we reconcile God’s time and created time?

Augustine’s most systematic attempt at a definition of divine time comes from book 11 of Confessions. It is there that the great doctor of the church sets out to understand what is meant by the opening words of Scripture: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen. 1:1). If it is true that God is immutable and unchangeable, what can it mean, Augustine wonders, that heaven and earth are “made” and that God is the one who does the “making”? “Earth and the heavens,” he writes, “are before our eyes. The very fact that they are there proclaims that they were created, for they are subject to change and variation.” In contrast, “there is nothing in [God] that was not there before.” Creation, then, is subject to change and bound by time, whereas Augustine argues that God suffers no change and is not bound by time.2

And yet, if God is changeless, what spurred the creation event? Or as Augustine puts it, “If the will to create something which he had never created before was new in him—if it was some new motion stirring in him—how can we say that his is true eternity, when a new will, which had never been there before, could arise in it?” Indeed. If the creation of heaven and earth represent an event in God’s own life, then, according to Augustine’s definition of eternity, the creator God is, in point of fact, not God at all. Alternatively, if God is not subject to change, then whatever God wills—for example, the creation—is willed eternally. But this also raises questions for Augustine, who asks, “Why is it that what he has created is not also eternal?”3 This explanation would seem to blur the temporal (if not the ontological) distinction between God and creation.

Augustine thinks that all of this is nonsense. He writes, “People who speak in this way have not learnt to understand you, Wisdom of God, Light of our minds.” He then presses his argument further, ratcheting up my every suspicion about this eternity to come: “In eternity, nothing moves into the past: all is present . . . . Your years are completely present to you all at once because”—and perhaps you can hear my ten-year-old self shudder here—“they are at a permanent standstill.”4

Here we have a static deity. The God set forth by Augustine in book 11 of Confessions is locked in a sort of everlasting now that can admit no trace of the divine motion, movement, and music that we saw in City of God. This is because, for Augustine, the past implies a falling away from reality whereas the future implies a coming-to-be of something, both of which are inadmissible in God. For this reason, he notes that in created time “it is abundantly clear that neither the future nor the past exist”—the very moment that the past becomes the past, it plunges into oblivion, and the future lies yet beyond the horizon as sheer possibility. Only “the present”—whatever that is; Augustine never really solves the riddle—is real.5

It should be noted how tantalizingly close Augustine comes to a conceptual breakthrough in the lines that follow when he remarks that “The present of past things is the memory; the present of present things is direct perception; and the present of future things is expectation,” but this does not at all help him on his quest to solve the mystery of created time. His commitment to the idea of eternity as a “permanent standstill” prevents him from entertaining the notion that God could be the one in whom memory (past), perception (present), and expectation (future) perfectly cohere in a sort of “eternal” or “divine time” that is constituted by the sheer plenitude of eternally interactive triune relationship rather than lack. Ultimately, however, he simply gives up the quest to make sense of God’s relationship to created time, saying in exasperation to the Lord, “I still do not know what time is . . . I am in a sorry state, for I do not even know what I do not know!”6

We can, I think, forgive the great bishop of Hippo for not successfully bridging his account of the pure being of God and the final destiny of created time. Working with the conceptual tools of his day, Augustine finally threw his hands up in despair at the possibility of meaningfully preserving God’s transcendent eternity while also giving a robust account of created time’s eschatological transfiguration in the triune God. And that, of course, is a central task of theology—stipulating the nature of that created time’s transfiguration without vitiating the transcendence of God.

But where, then, can I turn for help in sorting out my fright of heaven? I believe that the work of Robert W. Jenson, whom David Bentley Hart has called “America’s most creative systematic theologian,” could serve as a bridge between the being of God and the destiny of created time.7 Jenson’s work, which might be characterized as a sort of radical christological realism, provokes the imagination like few others, drawing out often unnoticed and therefore unexplored implications of the great orthodox confessions of the faith. Jenson emphasizes that the freely chosen being of God is determined by the history of Jesus Christ. The formula that he is perhaps most famous for summarizes the position exactly: “God is whoever raised Jesus from the dead, having before raised Israel from Egypt.”8

The formula plays nicely on the ears and certainly makes for a savory turn of phrase for the preacher (I should know, having used it many times before). But the longer one ponders it, the more provocative it becomes. Does Jenson mean to imply that somehow the twists and turns of created time belong to the identity of God? Yes, he answers without hesitation, writing, “It is the metaphysically fundamental fact of Israel’s and the church’s faith that its God is freely but, just so, truly self-identified by, and so with, contingent created temporal events. . . . These blatantly temporal events belong to his very deity.”9

For Jenson, this does not blur the distinction between God and the world. God remains God, and the world remains the world. He explains, “That God creates means there is other reality than God and that it really is other than he.” Creation is what happens when the triune God “make[s] accommodation in his triune life for other persons and things than the three whose mutual life he is. In himself,” Jenson writes, “he opens room, and that act is the event of creation.”10 The triune God and that which God creates remain ontologically distinct.

Nor is it to say that God would not have been this particular God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—without this particular history: “Presumably God could have been himself on different terms, established in his identity without reference to us or the time he makes for us. . . . But, of this possibility, we can assert only the sheer contrafactual; about how God would then have been the same God we now know, we can say nothing whatever.” He continues, with a statement that is crucial for the present argument: “As it is, God’s story is committed as a story with creatures.”11

For Jenson, this is to state what should have been obvious to orthodoxy all along: that this freely chosen history is the one history whereby we might know what God is really like—speaking, acting, healing, liberating. That is: God is interactive—for us secondarily; for Godself primarily: “The triune God is not a sheer point of presence; he is a life among persons. . . . The life of God is constituted by a structure of relations [Father, Son, and Holy Spirit] whose referents are narrative.”12

That is to say, the story of the Scripture is not just the story of humanity but also the story of the identity of God. Theology at its best does not shy away from this reality but honors it by handling it properly. Jenson notes: “‘The doctrine of the Trinity,’” to take one example, “is less a homogenous body of propositions than it is a task: that of the church’s continuing effort to recognize and adhere to the biblical God’s hypostatic being.”13 If the scriptural witness is true, we might say that God has chosen to be God in this way and no other.

Theology, in other words, ought to drive us back to the story, helping us to name rightly the God who freely identified the divine self with the twists and turns, triumphs and missteps, of the biblical narrative. And mutatis mutandis, Jenson wants us to understand that the biblical story is utterly decisive in our understanding of the identity of this God. All God-talk must therefore be anchored in the story of Israel and Jesus, to which the canon of Scripture bears witness.

One obvious implication of this perspective is that whatever is stipulated by the word God is now profoundly, unavoidably event-ed. The triune name Father, Son, and Holy Spirit designates for Jenson what we might call the personal evented eternity of God’s own life. God is the infinite dynamic relationality of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit that envelops created time in ontological coherence, itself enveloped by nothing, which is but a way of saying that the inner relational life of the eternal God is the very ground of all being.14

This is a very different vision of God than that found in Greek philosophy, according to Jenson, which tended to identify deity not by events in created time but by pure “metaphysical predicates,” chief among them “timelessness: immunity to time’s contingencies and particularly to death, by which temporality is enforced.”15 This understanding of deity as whatever is immune to time became the bugbear of a great many of the theological controversies that plagued the early church. Jensen goes so far as to claim that subordinationism, Arianism, Nestorianism, and other trends of thought that were finally condemned by the church found a common energy source in the unexamined Hellenistic assumption that a space for sheer timeless (and therefore un-evented, impassible) deity must be protected at all costs, even if it badly warped the gospel. Immunity to time is, for Jensen, the leaven that gave rise to so many early Christian heresies.

And thus, the church wrestled within itself for theological exactitude. Jenson notes:

It is easy to forget what these conceptual acrobatics are about. The identities are not counters in a metaphysical game; they are Jesus the Son and the God of Israel who he called “Father” and the Spirit of their future for themselves and us. The Cappadocian terms for their relations of origin—“begetting,” “being begotten,” “proceeding,” and their variants—are biblical words used to summarize the plot of the biblical narrative. . . . This narrative, asserts the doctrine of the Trinity, is the final truth of God’s own reality.”16

God, Jenson wants to say, over and over again, is the everlasting and personal event of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. God is identified not merely by but with our time, and God is revealed in our time as the God who overthrows the many dissonances wrought by sin in order that created time might find its consummation in divine time, in the eternal harmony that is the mutual, evented, and perfectly harmonious conversation we call Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Thus, the eschaton for Jenson looks something like this description from the conclusion to his two-volume systematics:

God will reign: he will fit created time to triune time and created polity to the perichoresis of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. God will deify the redeemed: their life will be carried and shaped by the life of Father, Son, and Spirit, and they will know themselves as personal agents in the life so shaped. God will let the redeemed see him: the Father by the Spirit will make Christ’s eyes their eyes. Under all rubrics, the redeemed will be appropriated to God’s own being. . . . The point of identity, infinitely approachable and infinitely to be approached, the enlivening telos of the Kingdom’s own life, is perfect harmony between the conversation of the redeemed and the conversation that God is. In this conversation, meaning and melody are one. The end is music.17

If Jenson’s insight into the nature of Godself—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—as the personal agents they eternally are for one another and also, just thereby, for us, is true, then it means something profound and liberating for our understanding of the future that God has prepared for us. It means that, odd as it may sound—and much to the relief of my ten-year-old self—there is a future for us in the eschaton.

Søren Kierkegaard said long ago that where the eternal touches the temporal, what is created is not a timeless present but instead the very thing by which personal beings of any kind are constituted: hope, possibility. “Eternally, the eternal is the eternal,” he wrote, but “in time the eternal is possibility, the future.”18 Human beings live by anticipation and fulfillment. Trinitarian theology, according to Jenson and others, stipulates that this is so because we are created in the imago Dei, the image of the triune God who as the mutual conversation among Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is both the everlasting anticipation and also the eternal fulfillment of God’s own being.

God, we might say, is God’s own eschaton, and everlastingly so. And we might say that God is also our eschaton. We will be fitted into the triune life, and there hope and possibility will not cease but will be elevated and transformed as we stretch out eternally toward God, as Gregory of Nyssa said, and toward one another in God. The delight of surprise that personal agents share will be ours unceasingly, never possessed but always given afresh, “further up and further in” (to quote C. S. Lewis in The Last Battle) with him, in what Jenson calls a “fugue” of love and joy and personal harmony that has no exterior, and no end.19 In this way, Augustine’s magnificent concluding lines to City of God will be proven true: “There we shall be still and see; we shall see and we shall love; we shall love and we shall praise. Behold what will be in the end without end! For what is our end but to reach that kingdom which has no end?20

- Augustine, City of God, 22.29, 22.30. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations are from City of God, trans. Henry Bettenson (London, UK: Penguin Classics, 2003).

- Augustine, Confessions, 11.4: “Whereas if anything exists that was not created, there is nothing in it that was not there before.” Note that I have substituted God for it, as Augustine later clarifies that the thing that exists that was not created is God. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations are from Confessions, trans. R. S. Pine-Coffin (London, UK: Penguin Classics, 1961).

- Augustine, Confessions, 11.10.

- Augustine, Confessions, 11.11, 11.13.

- Augustine, Confessions, 11.20.

- Augustine, Confessions, 11.20, 11.25.

- Hart, “The Lively God of Robert Jenson,” First Things, October 2005, https://www.firstthings.com/article/2005/10/the-lively-god-of-robert-jenson.

- Jenson, Systematic Theology, vol. 1, The Triune God (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1997), 63.

- Jenson, Triune God, 47–48 and 49.

- Jenson, Systematic Theology, vol. 2, The Works of God (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999), 5 and 25 (emphasis omitted).

- Jenson, Triune God, 65 (emphasis omitted).

- Jenson, Works of God, 35.

- Jenson, Triune God, 90.

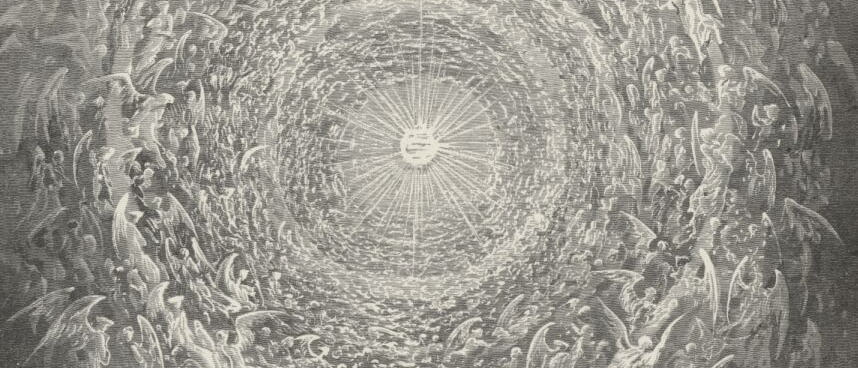

- The image conjures Dante Alighieri’s Paradiso: the triune God is the one who is “not circumscribed and circumscribing all” (The Divine Comedy: Paradiso, trans. Allen Mandelbaum [New York, NY: Everyman’s, 1995], canto 14, lines 28–30).

- Jenson, Triune God, 94.

- Jenson, Triune God, 108 (emphasis omitted).

- Jenson, Works of God, 369.

- Kierkegaard, Works of Love, trans. Howard Wong and Edna Hong (Harper Perennial: New York, 2009), 233–34.

- See Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses (New York, NY: Paulist, 1978), 30.113; Lewis, The Last Battle (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1984), 201; and Jenson, Triune God, 236.

- Augustine, City of God, 22.30.